Chapter 26 Treatment of Critical Left Main Bronchial Obstruction and Acute Respiratory Failure in the Setting of Right Pneumonectomy

Case Description

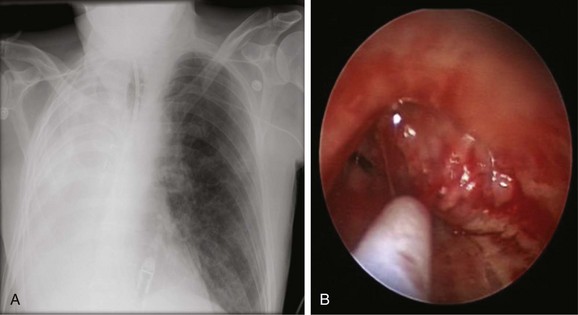

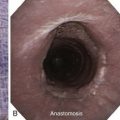

The patient was a 69-year-old Hispanic male who 6 days before arrival in our facility was admitted to an outside hospital with hypercapnic respiratory failure requiring endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. He had a history of COPD, atrial fibrillation, and asbestos exposure. Non–small cell lung cancer was diagnosed 5 years earlier, for which he underwent right pneumonectomy followed by systemic treatment with chemotherapy and radiation therapy. His medications included digoxin, Cardizem, Protonix, and albuterol and Atrovent nebulization. On examination, he had diffuse coarse breath sounds in the left lung field and diminished breath sounds on the right. The chest radiograph showed complete opacification of the right hemithorax consistent with his previous right pneumonectomy (Figure 26-1). Laboratory markers were normal, except for sodium of 128 mEq/L and albumin of 2.3 g/dL. Bronchoscopy showed a mass protruding from the medial wall of the distal left main bronchus, obstructing it by approximately 90% (see Figure 26-1). The patient’s wife and daughter were very involved in his care and stated that his goals were to be at home and not on life support.

Case Resolution

Initial Evaluations

Physical Examination, Complementary Tests, and Functional Status Assessment

In a critically ill patient with malignant central airway obstruction (CAO) who requires ventilatory assistance, interventional bronchoscopic procedures may be lifesaving, may allow extubation and time for additional therapies to be initiated, and may prolong survival.1–6 Reported overall median survival rates of critically ill patients with malignant CAO vary between 2 and 38 months post bronchoscopic interventions,1,6,7 and 1 year survival reportedly has been as low as 15%.8 This wide variability in results is probably explained by inclusion of patients at various stages of their disease, with those with various types of malignancies undergoing various treatments before and after interventions, and receiving different degrees of respiratory support. These critically ill patients are often admitted emergently to the intensive care unit (ICU) only when respiratory failure develops. According to Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) guidelines on ICU triage, admissions, and discharge, patients with advanced cancer should be admitted to the ICU when a reversible cause (e.g., pulmonary embolism, tamponade, airway obstruction) is identified.* Patients with advanced malignancy complicated by airway obstruction are given priority 3, which is defined as “unstable patients who are critically ill but have a reduced likelihood of recovery because of underlying disease or nature of their acute illness.”9 According to these guidelines, patients “may receive intensive treatment to relieve acute illness, however, limits on therapeutic efforts may be set, such as no intubation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation.” In practice, patients with acute respiratory failure usually are intubated, placed on mechanical ventilation, and transferred to the ICU. Patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and respiratory failure from CAO, such as our patient, therefore may warrant invasive mechanical ventilatory support and admission to the ICU, pending evaluation for palliative bronchoscopic interventions.10 If the bronchoscopic intervention is successful and the patient’s physiologic status has stabilized, ICU monitoring and care may no longer be necessary, and the patient can be transferred to a unit that provides a lower level of care. If, on the other hand, airway interventions are not successful, or if a patient’s physiologic status has deteriorated and active interventions are no longer planned, discharge to a lower level of care, including withdrawal of life support or referral to hospice, is a reasonable consideration. Families and referring physicians can be comforted by knowing that bronchoscopic intervention was not indicated, or that is was performed but was unsuccessful in alleviating the airway obstruction.

Many patients and their families may wonder whether all possible therapeutic alternatives are being considered, especially when the patient is possibly in the terminal stages of disease. Truthful disclosure by physicians is crucial in these instances to avoid compromising a physician-patient relationship built on trust. Although some patients and families are averse to truthfulness, most want their doctors to be honest and forthcoming in their communications about diagnosis and prognosis, even when it means announcing the likelihood of death. In addition to other factors, such as age and disease diagnosis, ethnicity may play an important role in a patient’s perceptions regarding truth telling and availability of therapeutic interventions. For example, approximately one in five deaths in the United States occurs in or shortly after a stay in the ICU,11 where evidence of disparities in end-of-life care has been found. In the United States, racial minorities apparently have been subjected to lower quality of care than whites,12 and although these findings are not consistent,*13,14 some studies report that African American patients receive fewer medical interventions, have shorter lengths of stay, and use fewer resources. One large study, however, evaluated the medical charts of patients who died in 15 intensive care units (3138 patients, of whom 2479 [79%] were white and 659 [21%] were nonwhite [e.g., African American, Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, Hispanic]). Logistic regression adjusted for socioeconomic factors measured by education, income, and insurance status showed that nonwhite patients were less likely to have living wills, were more likely to die with full support including cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and were more likely to die in a setting of full support than were white patients. In addition, nonwhites were more likely to have undergone medical interventions during their ICU stay, including dialysis, vasopressors, and mechanical ventilation.*15 Although all patients are and should be treated as VIPs (very important persons), consideration and respect for patient and family perceptions regarding therapy and truth telling are warranted, particularly if factors known to affect perceptions and behaviors are present.

The patient’s laboratory tests revealed hypoalbuminemia and moderate hyponatremia. The latter was likely due to the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion†16 because the patient was euvolemic, and no signs of hypovolemic hyponatremia, such as gastrointestinal losses, excessive diuresis or adrenal insufficiency, or salt wasting nephropathy or cerebral salt wasting, were noted. Other laboratory tests revealed a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level less than 10 mg/dL and urine osmolarity greater than 100 mOsm/kg of water—findings consistent with the diagnosis of SIADH.

Support System

In addition, differences in race, ethnicity, income, and education may have an effect on processes of care and outcomes. In the United States, results of studies show that patients with Medicaid* or no insurance had worse outcomes than other patients suffering from lung cancer. Although some of these disparities may have been secondary to confounding factors such as smoking and other health behaviors, available data suggest that patients with lung cancer without insurance do poorly because access to care is limited, and/or because they present with more advanced disease that is less amenable to treatment.17 On the other hand, the risk for Medicare† patients has been found to be similar to that for patients with private insurance; for those with Medicare disability insurance, no differences in stage were noted when a fee-for-service status was compared with a health maintenance organization or combination insurance status.18

Patient Preferences and Expectations

This patient with a known lung cancer had health care advance directives with regard to a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order in case of terminal irreversible disease. In general, published evidence reveals a low rate of completion of these documents among Hispanics.19 In addition to lack of trust in the health care system, health care disparities, and cultural perspectives on death and suffering, lack of acceptance of advance directives among Hispanics may originate from a view of collective family responsibility.20 In many Latin American countries, in fact, illness is viewed as a family affair rather than as a struggle of individual suffering. Before his respiratory failure, our patient had expressed his wish to not be on “breathing machines” if the disease process became irreversible. Therefore a DNR had been placed in his medical record upon his admission to the outside facility. One might recall that cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was originally designed for the prevention of sudden, unexpected death—not necessarily to prolong the life of an irreversibly terminally ill person.21 At the same time, the quality and duration of life-related value judgments should be avoided, and sanctity of life arguments can be made to justify CPR in virtually any setting.

In making decisions about code status orders, physicians and patients must communicate effectively, so that patients can receive informed and compassionate care that respects their wishes. Communication between physicians and patients (or their surrogates) about code status orders, however, is difficult, especially if matters are being discussed emergently at the time of a medical crisis. Misunderstandings about code status and overall goals of care preferences may lead to unwanted medical interventions or withholding/withdrawing of desired interventions. Results of studies show that patients in the ICU and their surrogates have insufficient knowledge about in-hospital CPR and its likelihood of success, such as whether CPR will result in preservation of life, preservation of organ function, discharge from an intensive care unit, or discharge alive from the hospital. In general, it appears that many patients, families, and physicians probably share an excessively positive estimation of the outcomes of CPR.22

A patient’s code status preferences may not always be reflected in code status orders, and assessments may differ between patients, their surrogates, family members, and physicians about what goal of care is most important.22 In our case, the patient’s family was particularly concerned that any de-escalation of the patient’s care, including proceeding with extubation or removal from mechanical ventilation, would constitute euthanasia. They also expressed firm disagreement with a proposed strategy of palliative sedation.* Oftentimes, when disagreements occur, an ethics consultation can help clarify terminology and avoid adversarial encounters between the treating team and the family. Anyone may request the assistance of ethics consultants, including family members and even health care providers not involved in the care of a particular patient if they sense impending difficulties in the medical encounters or in their own dealings with conflict. The involvement of other disciplines, including palliative care medicine, chaplaincy, and a social worker to address the family’s concerns, is a reasonable first step. In our case, physicians explained to the family that euthanasia is completely different from palliative sedation or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment based on its intent and outcome. In euthanasia, the intent is deliberate termination of a patient’s life (which is illegal in the United States), and palliative sedation is designed to relieve symptoms or the effects of burdensome interventions (i.e., mechanical ventilation). This is ethically justified and legal, even when sedation might cause, from its double effect, a hastened demise.23

Procedural Strategies

Indications

Relieving central airway obstruction could prevent post obstructive pneumonia, sepsis, and septic shock; allow extubation and a change in the level of care; permit initiation of systemic therapy; and potentially improve survival. Evidence suggests that bronchoscopic therapies often provide acute relief of the obstruction, improve quality of life, and serve as a therapeutic bridge until systemic treatments become effective.1,4,7 Subsequent systemic treatments (chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy) were shown to increase disease-free survival during the first year after restoration of airway patency.1,8

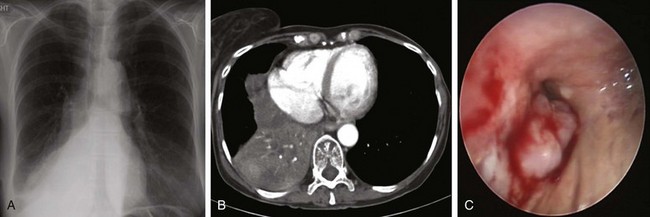

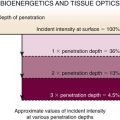

In patients with CAO (lobar or mainstem), assessing the functionality of the lung parenchyma distal to the obstruction is useful when interventions meant to establish airway patency are considered. Functionality of the lung distal to the obstruction may not be restored in patients who have had chronic complete obstruction and lack of ventilation (Figure 26-2). Determining whether there is functional airway and lung beyond an obstruction is essential for any successful bronchoscopic intervention,* in part because significant friability of bleeding from thin infiltrated bronchial mucosa, or lack of lung perfusion despite restored airway patency, might preclude intervention. In one study, 71% of patients who initiated radiation therapy within 2 weeks after radiologic evidence of atelectasis had complete re-expansion of their lungs, compared with only 23% of those irradiated after 2 weeks.24 Studies pertaining to successful bronchoscopic treatment and time to treatment are lacking.

One way to assess the perfusion status of lung parenchyma distal to an airway obstruction is to attempt bypass of the stenosis using a high-resolution endobronchial ultrasonography (EBUS) radial probe. For instance, the perfusion to one lobe could be completely shut down in a case of complete bronchial obstruction simply because of the Euler-Liljestrand reflex,† not because of pulmonary artery involvement. In cases of frank pulmonary artery occlusion, however, establishing airway patency could result in increased dead space ventilation. This finding should probably annul further intervention.25 Our patient had a critical distal left main bronchial obstruction in the setting of right pneumonectomy, but lobar and segmental airways in the left lung were patent bronchoscopically, and distal lung parenchyma appeared functional on the chest radiograph (see Figure 26-1).

Expected Results

Patients with advanced NSCLC and CAO who undergo successful interventional bronchoscopy to relieve airway obstruction might have a survival similar to those without CAO.26 Studies also show that patients with respiratory failure and malignant CAO palliated by bronchoscopic intervention who underwent additional definitive therapy survived longer (median, 38.2 months; range, 1.7 to 57.0 months) than those who did not (median, 6.2 months; range, 0.1 to 33.7 months; P < .001).7 Successful removal from mechanical ventilation in patients with CAO due to malignancy has been reported in 50% to 100% of patients in several small case series2,4 and, in some, prolonged survival was documented when systemic treatment was also administered (98 vs. 8.5 days).1

Therapeutic Alternatives

Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation and initiation of palliative sedation can be considered in patients with respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation in the setting of advanced malignant CAO and for whom no additional systemic or local (including bronchoscopy) therapies are indicated or feasible. These interventions, however, are used in patients who warrant aggressive symptom control and still have severe suffering (most commonly physical symptoms such as delirium, dyspnea, and pain) related to their underlying disease or therapy-related adverse effects.23 The effectiveness* of palliative sedation is in the range of 70% to 90%. In our patient, we decided to attempt relief of the airway obstruction using bronchoscopic techniques; had this been unsuccessful, we would have consulted palliative care medicine and discussed with the patient’s family withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments.23†

Informed Consent

The patient was sedated and was on mechanical ventilation. We discussed the indications, risks, benefits, and alternatives of bronchoscopic intervention with the patient’s wife and family during ICU family meetings. Using certified interpreters, we assessed their understanding of the proposed interventions and options—essential for an autonomous decision. Although it may seem paradoxical, patients and their surrogates benefit from the help of others to make truly autonomous decisions because they require accurate and comprehensive information. They may also need someone to help them relate the information they have to what they care about. Furthermore, because most people do not have a clear rank of priorities ready at hand for all situations, most need help identifying what they care about most and how this relates to the current health care encounter.27

Techniques and Results

Anesthesia and Perioperative Care

In the perioperative setting, anesthesiologists and surgeons may need to reconsider and re-evaluate standing DNR orders, which may need to be temporarily suspended during the intraoperative and immediate postoperative periods. Anesthesiologists may be skeptical of what they read in the patient’s chart, especially because it is possible that up until the time of the procedure, they usually know very little about the patient.* The surgeon may not be the patient’s primary physician and may not know the details of the circumstances in which the DNR decision was made. It is nearly impossible for advance directives to address adequately the multitude of clinical situations that may be encountered during the operative setting. CPR, if needed during the operative and immediate postoperative periods, includes not only chest compressions or electrical shocks, but also what could be viewed as excessive vasopressor usage or an inappropriate duration of resuscitation. Therefore it is important that all such patients be seen by the anesthesiologist and the surgeon preoperatively, and that a strategy be mutually agreed upon in case of the patient’s “death.” Although logistically difficult, a multidisciplinary discussion is warranted and might include the patient and/or the patient’s representative surrogate, the anesthesiologist, the surgeon, and the intensivist, who may be called upon postoperatively.28 A palliative care specialist or medical ethicist can also provide helpful insights. Multidisciplinary discussions may allow time to address the complex ethical and practical issues often present in these situations. For example, in the United States, patients who do not speak English fluently generally are less likely than more fluent English speakers to be actively engaged in end-of-life decision making, even in less hurried situations.29 Language barriers can be considerable, and working through translators, although necessary, is not always easy. Perioperative DNR orders also raise many issues of special concern. The DNR discussion with the patient or appropriate surrogate should include information about the characteristics of a possible resuscitation during the perioperative period; the risks, the benefits, and the likely outcome; and the reasons why resuscitation during the perioperative period might be determined by the patient, the surrogate, or the health care provider to be more or less burdensome than beneficial. If a surrogate is making the decision, the medical record should note the surrogate’s relationship to the patient (e.g., health care agent, spouse, guardian) and the basis on which the surrogate’s decision is made (e.g., “patient’s prior wishes,” “best interests”).

The DNR order should be written in detail and signed by one of the treating physicians. If the DNR order is cancelled preoperatively, as is often the case, then the time period and circumstances under which it is to be re-enacted should be specified.30 Interviews with terminally ill patients about perioperative resuscitative orders have revealed that some patients wanted their preoperative DNR orders revoked, some wanted to use procedure-directed perioperative DNR orders, and others wanted to redefine their goals for the procedure and postoperative outcome. This requires that the anesthesiologist and the surgeon decide about appropriate means for resuscitation during the procedure,31 and certain limits may be set. For example, we have seen patients with advanced illness having a respiratory arrest at the end of a procedure, who are responsive to intubation and ventilation but who never require chest percussion or vasopressors. We have also seen cardiac arrest rapidly reversible by defibrillation and not requiring reintubation or pressors. Special attention should be paid to issues related to the response to any iatrogenic arrest.32 Surrogates can be good decision makers for others when they know specifically what the person would have wanted, or when they have a strong general impression of that person’s values and beliefs. In some cases, however, surrogate decision making will be an approximation, subject to conscious and unconscious biases, concerns, and conflicts; in studies assessing agreement between a patient and surrogate regarding the use of CPR, the percent of agreement ranged from only 53% to 90%, with the frequency of agreement least in sicker patients.33

With regard to our patient’s preoperative physiologic optimization, fluid restriction (<1000 mL/day) was initiated during the ICU stay. Twenty-four hours later, his sodium had improved from 128 to 132 mEq/L. Had this not shown improvement, demeclocycline (300 to 600 mg orally twice daily), conivaptan (20 to 40 mg/day intravenously), tolvaptan (10 to 60 mg/day orally), or even hypertonic (3%) saline at less than 1 to 2 mL/kg/hr16* could have been used to correct hyponatremia preoperatively.

Anatomic Dangers and Other Risks

The descending aorta is posterior and the inferior pulmonary vein and left atrium are medial to the distal left main bronchus (LMB), where this patient’s tumor was located. Laser photocoagulation must be performed carefully in this area to avoid direct application onto the posterior and medial walls, which may result in high absorption of laser energy due to a hypervascular, hemorrhagic pattern of mucosal disease in this area and potential airway wall perforation. This is especially true in patients with pneumonectomy because normal anatomic relationships in the mediastinum have changed as a result of a postsurgical mediastinal shift. This also changes the alignment of bronchial structures in the chest—an important consideration when proceeding with rigid bronchoscopic debulking. Airway obstruction from blood and tumor debris in a patient with pneumonectomy may be fatal owing to severe impairment in gas exchange and refractory hypoxemia, and of course any obstruction of distal airways during resection will further compromise ventilatory and eventually hemodynamic status. Priority during resection in patients with only one lung should be given to ventilation and oxygenation, with recognition that in case of bleeding, it may be necessary to move the rigid tube beyond the obstruction, compressing the bleeding site with the tube itself, while ensuring ventilation through the distal patent segmental airways. Depending on the location of the bleed, one may wish to place the patient in a slightly head-down position so that blood moves proximally, protecting the distal airway, and if, for example, bleeding is coming from tumor along the medial wall of the left main bronchus, one might want to place the patient in the right lateral decubitus position, so that the rigid tube may more easily compress the bleeding site while maintaining ventilation of more distal bronchi.†

Results and Procedure-Related Complications

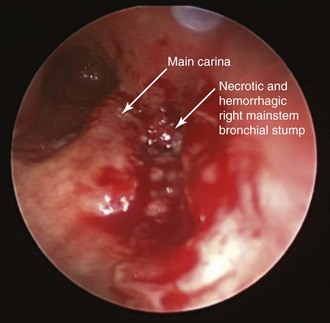

After administration of general anesthesia, the patient’s endotracheal tube (ETT) was removed under direct visualization, and he was intubated with a 13 mm Efer-Dumon rigid ventilating bronchoscope (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.26.1![]() ). Once inside the airways, a necrotic and infiltrated right bronchial stump was seen, suggesting recurrence of tumor, which posed a high risk for dehiscence (Figure 26-3); tumor was invading the main carina and the distal aspect of the right tracheal wall. In the distal left main bronchus, tumor extended for 1.5 cm, compressing and invading the airway and narrowing the lumen by 90% (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.26.2

). Once inside the airways, a necrotic and infiltrated right bronchial stump was seen, suggesting recurrence of tumor, which posed a high risk for dehiscence (Figure 26-3); tumor was invading the main carina and the distal aspect of the right tracheal wall. In the distal left main bronchus, tumor extended for 1.5 cm, compressing and invading the airway and narrowing the lumen by 90% (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.26.2![]() ). Flexible bronchoscopy performed through the rigid tube showed patent distal airways in the left upper and lower lobes. We decided to not insert a stent, but instead proceeded with bronchoscopic resection of the tumor. We initially performed laser photocoagulation of the right stump and carina to stop bleeding from the mucosal tumor. We then photocoagulated tumor in the distal left main bronchus by using a total of 442 Joules, applying 1 second 30 Watt Nd:YAG laser pulses. Tumor was partially debulked using the beveled edge of the rigid bronchoscope, and large pieces of tumor were removed and sent for histopathologic analysis. Abundant saline washings were performed to remove bloody secretions, tissue fragments, and small pieces of destroyed cartilage. At the end of the procedure, left bronchial patency had been restored (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.26.3

). Flexible bronchoscopy performed through the rigid tube showed patent distal airways in the left upper and lower lobes. We decided to not insert a stent, but instead proceeded with bronchoscopic resection of the tumor. We initially performed laser photocoagulation of the right stump and carina to stop bleeding from the mucosal tumor. We then photocoagulated tumor in the distal left main bronchus by using a total of 442 Joules, applying 1 second 30 Watt Nd:YAG laser pulses. Tumor was partially debulked using the beveled edge of the rigid bronchoscope, and large pieces of tumor were removed and sent for histopathologic analysis. Abundant saline washings were performed to remove bloody secretions, tissue fragments, and small pieces of destroyed cartilage. At the end of the procedure, left bronchial patency had been restored (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.26.3![]() ). We noted that tumor was extending distally all the way to the secondary left carina; therefore straight stent insertion would not have been ideal. The procedure was terminated, the rigid bronchoscope was removed, and the patient was reintubated as planned with a 7.5 ETT. He was transferred back to the medical ICU uneventfully.

). We noted that tumor was extending distally all the way to the secondary left carina; therefore straight stent insertion would not have been ideal. The procedure was terminated, the rigid bronchoscope was removed, and the patient was reintubated as planned with a 7.5 ETT. He was transferred back to the medical ICU uneventfully.

Long-Term Management

Outcome Assessment

Flexible bronchoscopy was performed the next day to remove mucus plugs and blood clots in the airways before a planned extubation was begun. The patient had been off narcotics and major sedatives and was fully awake but comfortable. The airways were patent, and no evidence of active bleeding was noted. We proceeded with the weaning protocol. Weaning parameters were not precluding extubation; however, the cuff leak volume was 100 mL. Testing for a cuff leak before endotracheal tube removal is a method commonly used to determine whether airway patency may be decreased. In this patient, the risk factors* for post extubation laryngeal edema included prolonged intubation (≥6 days) and the presence of a nasogastric tube that had been placed in the ICU.34 Normally, a cuff leak represents normal airflow around the ETT after the cuff of the ETT is deflated. Its absence suggests that space is reduced between the ETT and the supraglottic, glottis, or subglottic laryngeal structures. A pooled analysis found a sensitivity and specificity of only 56% and 92%, respectively, however, for predicting upper airway obstruction in adults.35 This may be due to the fact that reduced cuff leak volumes are explained not only by laryngeal edema, but also by secretions, or by the presence of an ETT that is large for that particular patient’s larynx. Cuff leak volume can be detected qualitatively† and quantitatively. Quantitative assessment is performed by deflating the ETT cuff and measuring the difference between inspired and expired tidal volumes of ventilator-delivered breaths during volume-cycled mechanical ventilation.‡36 Cuff leak volumes less than 110 mL (or <12% to 24% of the delivered tidal volume) have been suggested as thresholds for determining whether airway patency may be diminished. Even though many patients are safely extubated despite an absent cuff leak,37 it is reasonable to delay extubation if cuff leak is reduced and other risk factors for laryngeal edema are present. If a cuff leak is absent, management strategies include a course of glucocorticoid therapy,§38 extubation under bronchoscopic guidance, extubation over an airway exchange catheter, or extubation in a controlled environment with an anesthesiologist or other airway specialist at the bedside or in the operating room.39

In our patient, we chose to delay extubation for another day. The patient was administered a mild anxiolytic and was assured a good night’s sleep. The following day, a weaning trial was again performed, after which the patient was extubated over the flexible bronchoscope and placed on bilevel positive-pressure ventilation (settings 12/5 cm H2O). He was successfully weaned from bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) over the next 10 hours. Evidence suggests that noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation may prevent post extubation respiratory failure if it is applied immediately after extubation in patients requiring more than 48 hours of mechanical ventilation and considered at risk for developing post extubation respiratory failure. This includes patients with hypercapnia, congestive heart failure, ineffective cough and excessive tracheobronchial secretions, more than one failure of a weaning trial, multiple comorbidities, and upper airway obstruction.40 In our opinion, prolonged intubation in a poorly conditioned patient with respiratory failure, one lung, a history of lung cancer, recent general anesthesia, and successful debulking of an obstructing main bronchial obstruction also fits into this category.

Follow-up Tests and Procedures

The final diagnosis after microscopy showed invasive squamous cell carcinoma, moderately differentiated with necrosis. The patient’s functional status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] 4) was too compromised for him to undergo chemotherapy at that time, and his previous external beam radiation barred further radiation. Local control of the tumor in the left main bronchus after patency was re-established using Nd:YAG laser–assisted rigid debulking could have been possible with the use of high-dose brachytherapy. One of the main advantages of endobronchial brachytherapy (EBT) is its potentially longer-lasting effect and greater tissue penetration when compared with other endobronchial therapies. The effects of brachytherapy extend beyond the airway wall cartilage into the peribronchial tissues.41 In one study, the median time to symptom relapse was 4 to 8 months for all symptoms, and the median time to symptom progression was 6 to 11 months.41 EBT was shown to palliate dyspnea, hemoptysis, and cough in patients with poor performance status with a success rate of 53% to 95%42 and can be used in patients who have already received external beam radiation therapy,* as in our case.41,43

High response rates, however, are not consistent among studies. For example, one prospective study evaluated patients who had completed external irradiation at least 1 month before entry into the study. Outpatient bronchoscopic placement of one to three HDR brachytherapy catheters for delivery of 750 to 1000 cGy of intraluminal irradiation was performed every 2 weeks on one to three occasions. Only 5 of 18 patients had radiographic improvement in the extent of atelectasis, and response rates ranged from 25% for signs and symptoms related to pneumonitis to 69% for hemoptysis; performance status improved in only 24% of patients.43 In another series, on the other hand, when treatment was performed weekly and consisted of three to four 8 to 10 Gy fractions at a radius of 10 mm from the center of the source, symptomatic relief was obtained for hemoptysis in 74% and for dyspnea and cough in 54%, and a complete bronchoscopic response was noted in 54% of cases. Median survival was 7 months for the entire group.44 In a review of 11 studies using HDR, overall symptomatic improvement was seen in 60% to 90%, and better rates were reported for controlling hemoptysis.45 Patients who undergo brachytherapy should be carefully monitored for hemoptysis, which may be fatal in approximately 10% of patients. Although squamous cell pathology may be better controlled locally as compared with other histologic types,46 bleeding risks are increased.*47 Regardless of pathology, radiation bronchitis and stenosis (≈10%) may occur weeks to months after treatment, especially in patients who have undergone concurrent external beam radiation therapy or have had prior laser resection.48

Another justification for brachytherapy in this patient is that a multimodality bronchoscopic approach may be more effective than a single-modality approach for symptomatic palliation of lung cancer–related CAO. In one study comparing Nd:YAG laser, stent insertion, photodynamic therapy (PDT), or brachytherapy alone with a combination of bronchoscopic interventions such as laser and stent insertion, or laser and stent insertion closely followed by brachytherapy, significant improvements in survival were noted in the multimodality group (P = .04). One and 3 year cumulative survival rates for the two groups were 51.3% versus 50%, and 2.3% versus 22%, respectively, during the course of a 14 month follow-up.49 The type of modality used among patients from the single-modality group had no impact on survival, suggesting that it is restoration of airway patency that counts, not the method used to achieve it. Indeed, one might immediately remove a severe endoluminal exophytic obstruction using Nd:YAG laser–assisted debulking, for instance, and follow that with the use of a delayed effect therapy such as PDT or EBT. Using HDR brachytherapy as part of this strategy has been studied by several investigators50 and was shown to lessen disease progression and potentially reduce the cost of treatment when compared with repeated Nd:YAG laser treatments alone in advanced NSCLC.†50

Referrals

A few words are warranted with regard to interfacility transportation. In a health care system that comprises tertiary care facilities, regional referral centers, and both community and specialty hospitals, there is a need to practice patient transfers. Movement of patients between facilities is a process that can easily compromise a patient’s health, safety, and well-being, in addition to having financial and legal implications.51 Patient transfers occur for a variety of medical and nonmedical reasons. Certain diagnostic or therapeutic interventions may be unavailable at a transferring facility, for example, or a patient and family may request transfer to another hospital for personal reasons, for convenience (e.g., location), or for insurance reasons (e.g., hospital insurance contracts, network considerations).

Before transfer of a patient like ours is initiated, several parameters must be considered, including distance of travel, the cost-benefit ratio, logistics, specialized equipment needs, and, most important, safety for the patient and for transport personnel. Some authors suggest that ground systems be used for unstable patients when travel distance is less than 30 miles and for stable patients when the distance is less than 100 miles.52 Ground services may be provided by local Emergency Medical Services or by the transferring or receiving hospital. The decision to transfer our patient to our institution was made expediently once the diagnosis of airway obstruction was made. In many cases, however, patients can lie for days in a hospital bed while families, physicians, and insurers debate the costs and benefits of transfer. Direct communication between physicians at the referral center and accepting physicians at the place of transfer can be helpful. This ensures that clinical information is not lost or misunderstood by intermediaries.51 To optimize the transfer of an unstable patient, the referring (transferring) physician has the following obligations: (1) Document and discuss with the patient (or surrogates) that the benefits of transfer outweigh the risks, which include delayed care, further injury, disability, and death; (2) obtain informed consent from the patient or family, or implied consent if applicable; (3) arrange for the appropriate mode of transport with qualified personnel and equipment; (4) provide any treatments within the referring physician’s scope of practice and hospital capability that minimize the risk involved with the transfer; (5) arrange for a receiving hospital; and (6) deliver all applicable medical records, including diagnostic tests (e.g., imaging studies), to the receiving facility.53

Before the transfer occurs, the patient usually has already received the maximum amount of clinical care available from the referring institution. Those hospitals with the capability and capacity to care for patients requiring specialized tests or procedures such as interventional bronchoscopy, which are not available at a transferring facility, must accept the transfer, regardless of the reason,* including the patient’s inability to pay or lack of approval of the transfer by a managed care organization or an insurance provider.51 Depending on individual state laws, the accepting party does not have to be a physician and may be a hospital administrator, a nurse from a regional referral phone line, or another hospital designee. In our practice, direct communication with the referring physician is routine both before the patient is accepted and post intervention, before the patient’s transfer back to the referring facility. However, the actual transfer of the patient is sometimes impeded by lack of financial clearance due to specific health care insurance contracts.

Quality Improvement

We had not consulted the palliative care medicine team on this patient even though published evidence suggests that early referral to this service improves comfort and possibly survival.54 There is no doubt that it is preferable to have such teams involved because of their familiarity with palliative sedation strategies.23

With regard to this patient’s family’s perceptions of care in the ICU, a moral judgment might have been made by our ICU staff. Sociologic studies show no discretion in reflecting ascribed social and/or moral worth of patients. It is possible, however, that people are valued more or less on the basis of various social characteristics such as age, skin color, ethnicity, level of education, occupation, family status, social class, beauty, personality, talent, and accomplishments.55,56

Relevant to this case is that sometimes patients acquire labels even before they arrive at the hospital, potentially by manifesting excessively pessimistic behavior in the setting of respiratory failure. We have seen this in frail older persons with advanced lung cancer, but also in persons dealing with the anger of having become ill or the frustrations of loss of autonomy and independence. This provides an extra argument for individual ICUs to create admission policies that are specific to their unit. We believe that criteria for ICU admission of patients with NSCLC and CAO in respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilatory support should be explicitly described. This might lead to the selection of patients who are most likely to benefit from ICU care,9 including those patients who might benefit from palliative or curative bronchoscopic interventions. Relevant to our patient is that as of this writing, the SCCM recommends ICU admission for patients with acute respiratory failure requiring ventilatory support and for patients with airway obstruction, but these patients are given a priority 3, and it has been suggested that limits on therapeutic efforts such as no intubation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation should be set. Given the available evidence, we propose that these guidelines should be revised, and that many patients with acute respiratory failure due to central airway obstruction, whether or not they are already intubated, are very likely to benefit from expert bronchoscopic intervention.

Discussion Points

1. List two treatment alternatives that will fit the patient’s goals.

2. List four reasons for bronchoscopic intervention in a patient with malignant central airway obstruction and respiratory failure.

3. Describe three risks of bronchial stent insertion in this patient.

Expert Commentary

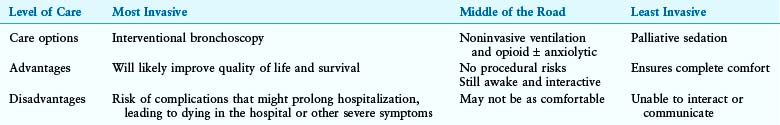

The approach of a palliative medicine consultant can be divided into two broadly distinct but related categories. One domain of the palliative medicine consultant is to assist the patient and the family in decision making. The other consists of pain and symptom management. In assisting with decision making, the palliative care team explores with the patient and family their goals of care. The palliative medicine consultant guides the patient and family through the informed decision-making process. The goal is not to tell them what to do, but instead to help them arrive at an answer that fits their priorities. Therefore we are more concerned about the validity of the process rather than the outcome, trusting that if the process is valid, the outcome too will be valid. True informed consent for any procedure requires that all alternatives (and their potential consequences) be explained, including that of not undergoing invasive or minimally invasive procedures. In my opinion, in cases such as the one described, all options are of palliative intent. Therefore a palliative medicine consultant is particularly well suited to assist the patient and family. We discuss a spectrum of care options with patients and their families, from the most aggressive or invasive to the most comfortable, supportive, and natural. As a general rule, I also offer one or two “middle of the road” alternatives because most people can handle only three or four options. We then discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each, always keeping in mind the primary goal of care. An example is provided in the accompanying Table 26-1, in which the primary goal of care is for the patient to be discharged from the hospital and return home.

When alternatives are described, it is essential to avoid confusion and to define carefully terms frequently used by health care providers in end-of-life settings. In this respect, a palliative care consultation can prove to be extremely beneficial. Palliative sedation, for example, must be distinguished from euthanasia* or physician-assisted death,† in that the intended outcome is comfort, not death. Palliative sedation is legal in every state in the United States. Several studies have shown that palliative sedation is effective in relieving symptoms and does not change the survival of end-stage patients.57,58 Because of these study results, many palliative medicine experts have argued that the ethical principle of double effect is no longer needed to justify the use of palliative sedation. The ethical principle of double effect argues that an intervention intended for good, such as high-dose opioids for the relief of pain, is appropriate, even if it runs the risk of harm, such as shortening a patient’s life.

* This intervention is used by the physician with the goal of terminating a patient’s life and is not legal in the United States.

† This intervention is prescribed by the physician and is used by the patient with the goal of terminating the patient’s life. In the United States, physician-assisted death is presently legal only in Oregon, Washington, and Montana.

Investigators have described several effective pharmacologic agents and approaches to palliative sedation.59 In practice, the choice of medications depends on the setting of care and other practical considerations. Short-acting benzodiazepines such as midazolam or lorazepam, for example, are generally the first choice in the ICU. My personal approach is to select a benzodiazepine that the patient has been given before. This approach reduces exposure of the patient to a new medication at the end of life, so as to minimize the risk for drug allergies or reactions. We certainly do not want the family’s last memory of their loved one to be that of the patient breaking out in a diffuse red rash. If discharge home or transfer to a medical ward is anticipated, then lorazepam is preferred because most nurses outside of the ICU are not comfortable with the use of midazolam. In addition, lorazepam can be administered as a subcutaneous infusion at home. Older patients are more likely to have a “paradoxical” response to benzodiazepines, especially at the middle range of the titration. Because benzodiazepines are frontal lobe disinhibitors, they trigger agitation in older patients and in patients with central nervous system disease before the sedation effect. To avoid this response, an antipsychotic can be given prophylactically, or the benzodiazepine can be rapidly titrated to deep sedation.

Outside of the ICU, barbiturates such as phenobarbital or pentobarbital may be preferred, especially in the geriatric population. These longer-acting medications have the advantage, however, of not wearing off during transportation or when parenteral access is lost, but they are more difficult to titrate. They can also be administered enterally through a feeding tube or rectally. Propofol is the agent of last resort, after standard palliative sedation agents have failed.60 In many hospitals, propofol is restricted to intubated patients already on ventilators because of its high risk of respiratory depression. Because of the need for close monitoring, its use is limited to the ICU, and it is not practical for patients to use at home.* Ketamine, when used for sedation, is generally restricted to use by anesthesiologists.

Clear titration parameters and goals should be given to nursing staff and pharmacists to distinguish palliative sedation from euthanasia. A sedation scale such as the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale can be used in the ICU. For non-ICU settings, the degree of sedation should be specified, such as “unresponsive to pain.” For patients with respiratory failure, deep sedation is generally warranted, although the degree of sedation may be adjusted according to the goals of care. Various protocols for palliative sedation and ventilator withdrawal have been published.61 For benzodiazepines in the ICU setting, my personal approach is to give a loading dose double that of the maximum dose the patient had been given previously. We then start an infusion at the same dose per hour as the loading dose and titrate every hour until the sedation goal is achieved—up to 5 times the starting dose. Intravenous barbiturates can be titrated every 4 to 6 hours, using a loading dose of 60 to 100 mg and an initial rate of 30 to 60 mg per hour, depending on the age and size of the patient. A typical therapeutic dose ranges between 50 and 100 mg per hour. Rarely is 120 mg an hour or more needed. Conversion from intravenous to enteral administration is 1 : 1. Maintenance enteral administration is provided every 8 hours.

Although artificial* hydration and nutrition can be administered during palliative sedation, this generally is not recommended at the end of life. Administration of artificial hydration and nutrition in patients with advanced cardiopulmonary conditions can, in fact, worsen their symptoms. Furthermore, hydration and nutrition have not been shown to prolong survival in end-stage patients.

A final point I would like to mention is that regardless of the palliative care option selected, home care possibilities should be discussed with the patient if possible and of course with the family. These are not always easy conversations, and they must be quite detailed to avoid misunderstandings and to ensure that the appropriate level of care and support is being provided. Consultation with case management and palliative medicine is therefore important. In the United States, it is often necessary to discuss financial matters, such as insurance coverage, possible out-of-pocket expenses for uncovered services, or costs of medications.† In no way should the patient or the patient’s family feel as if they have been abandoned. In my opinion, the patient presented in this chapter could have been discharged directly to hospice without returning to the referring hospital. A direct home discharge, with the approval of the referring physician, would have maximized home time for the patient and family and would have decreased costs to the health care system.

1. Stanopoulos IT, Beamis JFJr, Martinez FJ, et al. Laser bronchoscopy in respiratory failure from malignant airway obstruction. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:386-391.

2. Colt HC, Harrell J. Therapeutic rigid bronchoscopy allows level of care changes in patients with acute respiratory failure from central airways obstruction. Chest. 1997;112:202-206.

3. Shaffer JP, Allen JN. The use of expandable metal stents to facilitate extubation in patients with large airway obstruction. Chest. 1998;114:1378-1382.

4. Lo CP, Hsu AA, Eng P. Endobronchial stenting in patients requiring mechanical ventilation for major airway obstruction. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:66-70.

5. Wood DE, Liu YH, Vallières E, et al. Airway stenting for malignant and benign tracheobronchial stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:167-174.

6. Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Postmus PE, Sutedja TG. Tracheobronchial stenting in the terminal care of cancer patients with central airways obstruction. Chest. 2001;120:1811-1814.

7. Jeon K, Kim H, Yu CM, et al. Rigid bronchoscopic intervention in patients with respiratory failure caused by malignant central airway obstruction. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:319-323.

8. Lemaire A, Burfeind WR, Toloza E, et al. Outcomes of tracheobronchial stents in patients with malignant airway disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:434-438.

9. Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge, and triage, Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:633-638.

10. Murgu SD, Langer S, Colt HG. Success of bronchoscopic intervention in patients with acute respiratory failure and inoperable central airway obstruction from non small cell lung carcinoma. Chest. 2010;138(suppl 4):720A.

11. Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638-643.

12. Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, et al. Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5559-5564.

13. Williams JF, Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP, et al. African-American and white patients admitted to the intensive care unit: is there a difference in therapy and outcome? Crit Care Med. 1995;23:626-636.

14. Degenholtz HB, Thomas SB, Miller MJ. Race and the intensive care unit: disparities and preferences for end-of-life care. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S373-S378.

15. Muni S, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, et al. The influence of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139:1025-1033.

16. Pelosof LC, Gerber DE. Paraneoplastic syndromes: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:838-854.

17. Slatore CG, Au DH, Gould MK, American Thoracic Society Disparities in Healthcare Group. An official American Thoracic Society systematic review: insurance status and disparities in lung cancer practices and outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1195-1205.

18. Roetzheim RG, Chirikos TN, Wells KJ, et al. Managed care and cancer outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:287-296.

19. Blackhall LJ, Murphy ST, Frank G, et al. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA. 1995;274:820-825.

20. Morrison RS, Zayas LH, Mulvihill M, et al. Barriers to completion of healthcare proxy forms: a qualitative analysis of ethnic differences. J Clin Ethics. 1998;9:118-126.

21. American Heart Association. Standards and guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiac care (ECC): medicolegal considerations and recommendations. JAMA. 1974;227(suppl):864-866.

22. Gehlbach TG, Shinkunas LA, Forman-Hoffman VL, et al. Code status orders and goals of care in the medical ICU. Chest. 2011;139:802-809.

23. Olsen ML, Swetz KM, Mueller PS. Ethical decision making with end-of-life care: palliative sedation and withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:949-954.

24. Reddy SP, Marks JE. Total atelectasis of the lung secondary to malignant airway obstruction: response to radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13:394-400.

25. Shirakawa T, Ishida A, Miyazu Y, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound for difficult airway problems. In: Bolliger CT, Herth FJF, Mayo PH, et al. Clinical Chest Ultrasound: From the ICU to the Bronchoscopy Suite. Basel: Karger; 2009:189-201.

26. Chhajed PN, Baty F, Pless M, et al. Outcome of treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer with and without central airway obstruction. Chest. 2006;130:1803-1807.

27. Hawkins J. Making autonomous decisions: million dollar baby. In: Colt HG, Quadrelli S, Friedman L. The Picture of Health: Medical Ethics and the Movies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

28. Waisel DB, Truog RD. The end-of-life sequence. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:676-686.

29. Thompson BL, Lawson D, Croughan-Minihane M, et al. Do patients’ ethnic and social factors influence the use of do not resuscitate orders? Ethn Dis. 1999;9:132-139.

30. Walker RM. DNR in the OR: resuscitation as an operative risk. JAMA. 1991;266:2407-2412.

31. Truog RD, Waisel DB, Burns JP. DNR in the OR: a goal-directed approach. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:289-295.

32. Waisel DB, Burns JP, Johnson JA, et al. Guidelines for perioperative do-not-resuscitate policies. J Clin Anesth. 2002;14:467-473.

33. Seckler AB, Meier DE, Mulvihill M, et al. Substituted judgment: how accurate are proxy predictions? Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:92-98.

34. Kriner EJ, Shafazand S, Colice GL. The endotracheal tube cuff-leak test as a predictor for postextubation stridor. Respir Care. 2005;50:1632-1638.

35. Ochoa ME, Marín Mdel C, Frutos-Vivar F, et al. Cuff-leak test for the diagnosis of upper airway obstruction in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1171-1179.

36. Miller RL, Cole RP. Association between reduced cuff leak volume and postextubation stridor. Chest. 1996;110:1035-1040.

37. Engoren M. Evaluation of the cuff-leak test in a cardiac surgery population. Chest. 1999;116:1029.

38. Epstein SK. Preventing postextubation respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1547.

39. Mort TC. Continuous airway access for the difficult extubation: the efficacy of the airway exchange catheter. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1357-1362.

40. Nava S, Gregoretti C, Fanfulla F, et al. Noninvasive ventilation to prevent respiratory failure after extubation in high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2465-2470.

41. Mallick I, Sharma SC, Behera D. Endobronchial brachytherapy for symptom palliation in non-small cell lung cancer—analysis of symptom response, endoscopic improvement and quality of life. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:313-318.

42. Vergnon JM, Huber RM, Moghissi K. Place of cryotherapy, brachytherapy and photodynamic therapy in therapeutic bronchoscopy of lung cancers. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:200-218.

43. Hernandez P, Gursahaney A, Roman T, et al. High dose rate brachytherapy for the local control of endobronchial carcinoma following external irradiation. Thorax. 1996;51:354-358.

44. Taulelle M, Chauvet B, Vincent P, et al. High dose rate endobronchial brachytherapy: results and complications in 189 patients. Eur Respir J. 1998;11:162-168.

45. Michailidou I, Becker HD, Eberhardt R. Bronchoscopy high dose rate brachytherapy. In: Strausz J, Bolliger CR. Interventional Pulmonology. Lausanne, Switzerland: European Respiratory Society; 2010:173-189.

46. Huber RM, Fischer R, Hautmann H, et al. Does additional brachytherapy improve the effect of external irradiation? A prospective, randomized study in central lung tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:533-540.

47. Hara R, Itami J, Aruga T, et al. Risk factors for massive hemoptysis after endobronchial brachytherapy in patients with tracheobronchial malignancies. Cancer. 2001;92:2623-2627.

48. Speiser B, Spratling L. Intermediate dose rate remote afterloading brachytherapy for intraluminal control of bronchogenic carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;18:1443-1448.

49. Santos RS, Raftopoulos Y, Keenan RJ, et al. Bronchoscopic palliation of primary lung cancer: single or multimodality therapy? Surg Endosc. 2004;18:931-936.

50. Chella A, Ambrogi MC, Ribechini A, et al. Combined Nd-YAG laser/HDR brachytherapy versus Nd-YAG laser only in malignant central airway involvement: a prospective randomized study. Lung Cancer. 2000;27:169-175.

51. Blackwell TH. Interfacility transports. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;23:11-18.

52. Brink LW, Neuman B, Wynn J. Air transport. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1993;40:439-456.

53. Bitterman RA. EMTALA. In: Henry GL, Sullivan DJ. Emergency Medicine Risk Management: A Comprehensive Review. 2nd ed. Dallas, Tex: American College of Emergency Physicians; 1997:103-123.

54. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733-742.

55. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The social loss of dying patients. Am J Nurs. 1964;64:119-121.

56. Hill TE. How clinicians make (or avoid) moral judgments of patients: implications of the evidence for relationships and research. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2010;5:11.

57. Mercadante S, Intravaia G, Villari P, et al. Controlled sedation for refractory symptoms in dying patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:771-779.

58. Maltoni M, Pittureri C, Scarpi E, et al. Palliative sedation therapy does not hasten death: results from a prospective multicenter study. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1163-1169.

59. Cherny NI, Radbruch L, Board of the European Association for Palliative Care. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2009;23:581-593.

60. Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Crowley L, et al. Evaluation of a standardized order form for the withdrawal of life support in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1141-1148.

61. Dalal S, Del Fabbro E, Bruera E. Is there a role for hydration at the end of life? Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009;3:72-78.

* The prioritization model used for this purpose defines those patients who will benefit most from the ICU (priority 1) versus those who will not benefit at all (priority 4) from ICU admission.

* This discrepancy appears to be largely due to the fact that the studies showing nonwhite patients receiving more life-sustaining measures focused on patients dying in the ICU and, therefore, reflect life-sustaining treatments provided during end-of-life care.

* Nonwhite patients were also more likely to have documentation that the prognosis was discussed and that physicians recommended withdrawal of life support, and were more likely to have discord documented among family members or with clinicians, but the socioeconomic status did not modify these associations and was not a consistent predictor of end-of-life care. With regard to truth telling, at least one study in the United States suggests that in case of serious illness, elderly European Americans and African Americas were more likely to believe they should be told the truth about diagnosis and prognosis than were Korean Americans and Mexican Americans (Blackhall L. Should patients always be told the truth? AORN J. 1988;47:1306-1310).

† SIADH is seen in 1% to 2% of patients with lung cancer (usually caused by small cell carcinoma). Signs and symptoms of SIADH (gait disturbances, falls, headaches, muscle cramps, confusion, lethargy, seizure, and even respiratory failure and coma) usually occur with acute and more severe hyponatremia (sodium <125 mEq/L).

* Medicaid is a joint federal-state program designed to provide financial assistance to eligible low-income low-asset persons (people with disabilities, children, parents of eligible children, pregnant women, elderly nursing home residents, and those with certain diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS] and minimal assets based on percentage of the Federal Poverty Level). Currently, more than 50 million persons in the United States, including millions of children and more than 60% of nursing home residents, are covered by Medicaid programs.

† Medicare is a federal health insurance program that covers people age 65 and older and those younger than 65 with certain disabilities, such as permanent kidney failure. Legal residence in the United States for at least 5 years is mandatory for eligibility. Medicare Part A covers inpatient hospital stays, residence in skilled nursing facilities, and hospice or home care and may be premium free. Medicare Part B covers required outpatient and some preventive services and has a monthly premium. Medicare prescription coverage can be purchased, and Medigap coverage (Medicare supplement insurance) is available to pay for uncovered costs such as deductibles and copayments.

* Palliative sedation refers to the use of medications to induce decreased or absent awareness to relieve otherwise intractable suffering.

* Other conditions include experienced bronchoscopist and team; experienced anesthesiologist; control of patient’s overall performance status; whether additional systemic or local therapy is still possible; and control of comorbidities.

† The Euler–Liljestrand reflex describes the relation between ventilation and perfusion in the lung. If the ventilation in a part of the lung decreases, this leads to local hypoxia and to vasoconstriction in that particular lung region. This adaptive mechanism is beneficial because it diminishes the amount of blood that passes the lung without being oxygenated, thus avoiding ventilation-perfusion mismatch and hypoxemia.

* Defined as the patient’s, family’s, or physician’s perceived relief of refractory physical symptoms.

† With this end-of-life decision making, the cause of death is the underlying disease, but the intent is to remove burdensome interventions (e.g., mechanical ventilation); this is a legal practice in United States, but several states limit the power of surrogate decision makers regarding life-sustaining treatment.

* The ability of anesthesiologists to re-evaluate the DNR order is also hampered by the lack of a system that allows early notification of pending cases, which would give the anesthesiologist ample time to discuss these issues with the patient, family caregivers, the surgeon, and other health care providers.

* Rapid correction can occur with hypertonic saline, and this can lead to water egress, brain dehydration, and central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis, characterized by lethargy, dysarthria, spastic quadriparesis, and pseudobulbar palsy; therefore the correction rate should not be faster than 0.5 to 1 mmol/L/hr.

† Note that in this situation, the adage of “bleeding side down” applies to the medial wall of the bronchus, not to the right or left hemithorax.

* Other risk factors for laryngeal edema include age greater than 80 years, female gender, an elevated Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score less than 8, a large endotracheal tube (>8 mm in men, >7 mm in women), a ratio of ETT to laryngeal diameter greater than 45%, a small ratio of patient height to ETT diameter, traumatic intubation, excessive tube mobility due to insufficient fixation, insufficient or lack of sedation, and aspiration.

† The qualitative assessment is done by deflating the ETT cuff and listening for air movement around the ETT using a stethoscope placed over the upper trachea after deflating the ETT cuff.

‡ The lowest three expired tidal volumes obtained over six breaths are averaged and then subtracted from the inspired tidal volume to obtain the cuff leak volume.

§ One potential regimen in patients with reduced cuff leak volume and with risk factors for post extubation stridor includes administration of methylprednisolone 20 mg intravenously every 4 hours for a total of four doses before extubation.

* In previously nonirradiated patients with a good performance status, high-dose-rate (HDR) brachytherapy cannot be offered as the only modality in primary palliative treatment.

* Other risk factors for hemoptysis when brachytherapy is used include tumors located in the mainstem or upper lobe bronchi, irradiation in the vicinity of a large vessel, and doses greater than 10 Gy/fraction.

† Results of this study show that the symptom-free period was 2.8 months for the Nd:YAG laser group and increased to 8.5 months for the combination modality group (P < .05). The progression-free period of the disease increased from 2.2 months to 7.5 months (P < .05), and the number of additional endoscopic treatments was reduced from 15 to 3 (P < .05).

* 42 USC 1395dd, The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act.

* As evidenced by the Michael Jackson case, albeit for a different indication.

* Artificial nutrition and/or hydration is an intervention that delivers nutrition and/or fluids by means other than taking something in the mouth and swallowing it.

† Both Medicare and Medicaid provide hospice care and home palliative care. Home palliative care is covered as a skilled need for pain and symptom management. Under Medicare, hospice can provide 24 hour home care if an uncontrolled problem exists that needs continued monitoring and intervention, such as palliative sedation. Hospice pays for all comfort-related measures such as medications, oxygen, and durable medical equipment. Home palliative care does not. On the other hand, while on palliative care, patients may continue to receive interventions such as chemotherapy and radiation and may undergo diagnostic and interventional procedures or blood transfusions, or they may receive parenteral nutrition; these are services that hospice does not cover. Patients can move back and forth between hospice and home palliative care without penalties.