3 Treatment of bipolar depression

3.1 What is the best medication for depression in someone who has a history of mania (bipolar I depression)?

![]() Giving antidepressants on their own to a patient with a history of mania is not to be recommended because antidepressants can precipitate mania (see Q 3.15).

Giving antidepressants on their own to a patient with a history of mania is not to be recommended because antidepressants can precipitate mania (see Q 3.15).

Another reason to avoid monotherapy with antidepressants is that the commonest time to become manic is following an episode of depression and consideration should be given to how to prevent this happening. Although antidepressants are the mainstay of treatment for bipolar depression they should only be used in combination with a medication that will prevent mania (see Q 3.6).

3.3 Which types of antidepressant are commonly available?

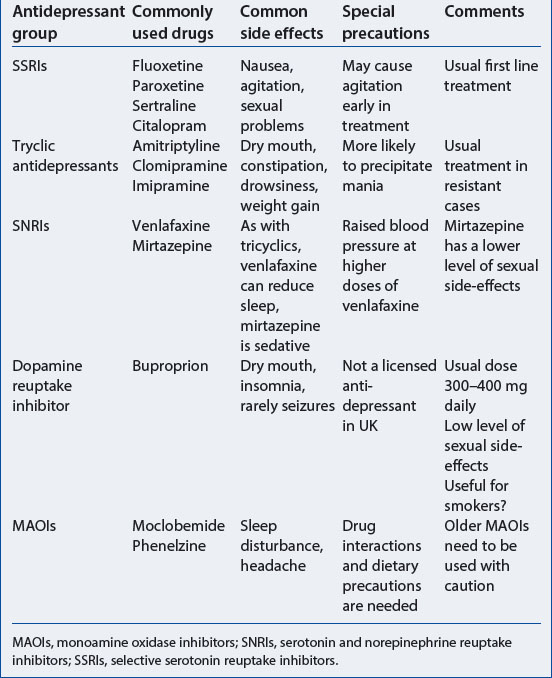

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly used antidepressants in the UK. They are not only the first line treatment for unipolar depression but also the first line treatment for bipolar depression. Tricyclic antidepressants are also effective in the treatment of both unipolar and bipolar depression (Table 3.1).

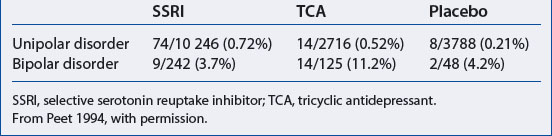

The benefits of SSRIs over tryclics are that they are simple to take (usually once daily dosage) and the initial dose is usually an effective dose. In addition, SSRIs are less likely to cause manic switch than tricyclics (Table 3.2). In contrast the tricyclics require a gradual increase to an effective dose because of side-effects, usually over at least 2 weeks. The level of side-effects of SSRIs is low and they are relatively safe if taken in overdose.

There have been reports that agitation and suicidal impulses may be increased in the first few weeks on SSRIs (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency 2003). It is difficult to disentangle this effect from a deteriorating depression which is not responding to treatment, as suicidal thoughts are an integral part of depression (see Q 1.8).

3.4 Are there any other types of antidepressant used in the treatment of bipolar depression?

MOCLOBEMIDE

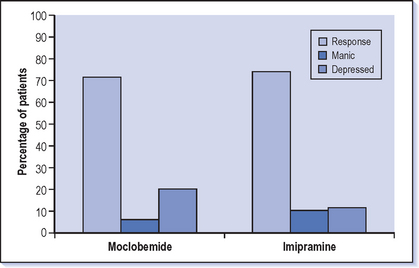

Moclobemide (Manerix) has been shown to be effective and to have a low propensity for ‘switch’ into mania compared to the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine (Silverstone 2001) (Fig. 3.1). Moclobemide is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) which often worries prescribers because of concerns about dangerous interactions with foods (the cheese reaction occurs when the amino acid tyramine passes through the gut without being broken down and leads to a rise in blood pressure). However, moclobemide is a specific inhibitor of monoamine oxidase in the brain and does not inhibit the form found in the gut. Tyramine can therefore still be broken down in the gut and so does not get through to cause a hypertensive reaction. Moclobemide is also a reversible inhibitor and is relatively short lived so there is only a short (days) wash-out period before another antidepressant can be started if there is a need to change treatment.

3.5 For how long should antidepressants be continued after recovery from depression?

The concern for bipolars who continue antidepressants is that they may be running an increased risk of mania while they are on this treatment. Because of this it would be recommended to discontinue antidepressants at an early stage after recovery from bipolar depression at about 3 months. This is in contrast to the advice for those with unipolar depression which is to continue the antidepressants for at least 6 months after recovery. Unipolar depressives are also often advised to take antidepressants long term as preventive treatment; however this would not usually be appropriate for bipolars.

For bipolars consideration needs to be given to effective long-term preventive treatment such as lithium (see Chapter 4). If they are to continue with antidepressants they must also take an antimanic drug, such as lithium, an antipsychotic or valproate (see Q 3.7).

3.6 Should bipolars continue on their long-term preventive treatment if they become depressed?

![]() Definitely. It is very important that long-term prophylactic treatment (e.g. with lithium) is continued when the patient becomes depressed. This is because the depression is most likely being treated with antidepressants and if the lithium is stopped there is an increased chance of switching into mania (Fig. 3.2). Obviously at some point the patient will need to be reviewed to assess how effective the preventive treatment is, but the usual time to do this is after recovery from the acute episode of depression.

Definitely. It is very important that long-term prophylactic treatment (e.g. with lithium) is continued when the patient becomes depressed. This is because the depression is most likely being treated with antidepressants and if the lithium is stopped there is an increased chance of switching into mania (Fig. 3.2). Obviously at some point the patient will need to be reviewed to assess how effective the preventive treatment is, but the usual time to do this is after recovery from the acute episode of depression.

3.7 Is there a role for long-term antidepressants as a way of preventing depression recurring in bipolars?

Many bipolar II patients are treated successfully in the long term with antidepressants without lithium or other preventive treatments. This usually follows on from a period of treatment with antidepressants that has been successful without a switch into hypomania. As long as an eye is kept on making sure that elated periods are not occurring, then this is a reasonable option. However, there is a need to be wary as many of those who suffer from hypomanias are not good at recognising them or tend to play down the problems that they cause. Ask someone else in the family if the patient is getting on reasonably.

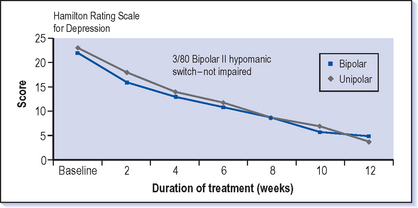

3.8 What is the best medication for depression in someone who has a history of hypomania but has never been manic (bipolar II depression)

The mainstay of treatment for bipolar II depression is antidepressants, one option being the SSRI fluoxetine (Fig. 3.3). However, the initial decision to be made is whether to prescribe a drug that will prevent manic symptoms developing in addition to the antidepressant. This is a matter of judgement–at one end of the scale a patient who has had only short-lived and not disabling hypomania in the past is suitable for antidepressant treatment on its own but with monitoring for the appearance of manic symptoms. At the other end, someone who is currently depressed but with previous prominent, frequent and socially disabling hypomania should certainly be taking treatment to prevent further manic symptoms along with the antidepressant. Judging where a patient is on this spectrum is difficult and prescribing treatment often requires a lot of negotiation as many patients will be keen to relieve the depression but may not be concerned about hypomanic symptoms. It is usually the case that the manic depressive patient is very keen to relieve and prevent depression but the family (and others including doctors) are more concerned about the social disruption of hypomania.

Fig. 3.3 Treatment of depression with fluoxetine in bipolar and unipolar patients.

(From Amsterdam et al 1998, with permission.)

CASE VIGNETTE 3.1 ANTIDEPRESSANTS MAY DESTABILISE THE COURSE OF BIPOLAR ILLNESS

CASE VIGNETTE 3.1 ANTIDEPRESSANTS MAY DESTABILISE THE COURSE OF BIPOLAR ILLNESS

A bad spell of depression then hit her and she was off work for a month and started treatment with an antidepressant. This seemed to get her right within a couple of weeks but she went a bit more over the top and to her embarrassment ended up sleeping with one of her salesman who was 10 years her junior. This led to another spell of depression but an increase in the antidepressant again led to improvement. However, by the end of the year she was feeling ‘all over the place’, never knowing how her mood was going to be week to week. Her work was going badly as she was now regarded as a liability when previously reliability was her middle name.

3.9 What if the depression is not improving with antidepressant treatment?

The following questions should be considered before contemplating a change in medication:

Have you given the treatment long enough?: At least 4 weeks with no response, or 6 weeks with only minor response. It can be difficult to stick with the treatment when there is little improvement; a realistic time scale for improvement should be discussed with the patient from the beginning–it may well take up to 4 weeks to start to see a difference. It is also worth discussing at this point the balance between the time needed to give this treatment a good try against the time it will take to make a changeover to another medicine. Focusing on other ways that the patient can help to make a difference to the level of depression is also useful (see Qs 3.29 and 3.36).

Have you given the treatment long enough?: At least 4 weeks with no response, or 6 weeks with only minor response. It can be difficult to stick with the treatment when there is little improvement; a realistic time scale for improvement should be discussed with the patient from the beginning–it may well take up to 4 weeks to start to see a difference. It is also worth discussing at this point the balance between the time needed to give this treatment a good try against the time it will take to make a changeover to another medicine. Focusing on other ways that the patient can help to make a difference to the level of depression is also useful (see Qs 3.29 and 3.36). Have you tried a high dose?: If the patient is not improving, doses should be increased to the maximum, provided that the treatment is reasonably tolerated before turning to an alternative antidepressant.

Have you tried a high dose?: If the patient is not improving, doses should be increased to the maximum, provided that the treatment is reasonably tolerated before turning to an alternative antidepressant. Have you assessed concordance/compliance?: Is the patient really in agreement with this treatment and taking it (see also Q 5.43)? Are they forgetting because they are feeling so tired, lethargic and can’t remember to do anything including taking the tablets? Is there some way of improving this–linking it with some more routine or habitual aspect of their life (e.g. brushing their teeth)?

Have you assessed concordance/compliance?: Is the patient really in agreement with this treatment and taking it (see also Q 5.43)? Are they forgetting because they are feeling so tired, lethargic and can’t remember to do anything including taking the tablets? Is there some way of improving this–linking it with some more routine or habitual aspect of their life (e.g. brushing their teeth)?3.10 What are the next lines of treatment in bipolar depression that has not responded to the first antidepressant treatment?

If this is not successful, continue the lithium but change the antidepressant to a different class of drug. It would be worth reviewing what treatments the patient has been on previously to see if it is possible to identify another drug that has been helpful in the past. If no clear treatment option is apparent the usual rule of thumb is that if the patient has been on an SSRI, change to a tricyclic and vice versa.

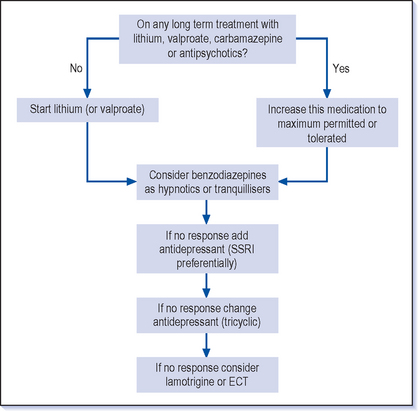

Other options that are available include other groups of antidepressants, thyroid hormone (at above replacement levels), lamotrigine, tryptophan or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (see Q 3.22) (Fig. 3.4) and psychotherapeutic talking treatments (see Qs 3.20 and 5.46).

3.13 Is the treatment for depression in adolescents different?

There are very few trials of treatment of bipolar depression but there are virtually no data on the treatment of bipolar depression in adolescents. There have been concerns that unipolar depression in this age group does not show a good response to antidepressant medication. This is difficult to reconcile with the data for adults which show a clear benefit in improving depression–is there some basic change in depression and its response to treatment at 18 (or 17)? There are also concerns that some antidepressants (SSRIs) can cause agitation and an increase in suicidal thoughts and behaviour, and that this effect is more marked in adolescents.

Overall, even more care needs to be taken when considering the treatment for bipolar depression in adolescents. However, the same lines of treatment as for adults should be followed. Keeping a long-term perspective and focusing on appropriate longer term preventive treatment is a good basic principle, though severe depressive episodes will require antidepressant treatment despite the current uncertainties.

3.14 Should low level depressive symptoms be treated?

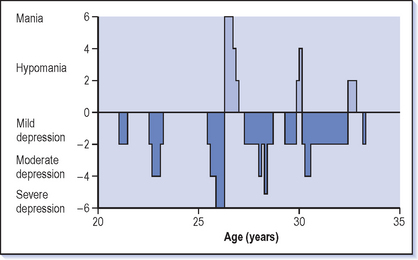

As indicated in Chapter 2, chronic depressive symptoms are the most frequent long-term problem for bipolars (Fig. 3.5) and we are probably too reticent about treating these. This is partly because it is the manic symptoms that tend to be much more obvious to health professionals and family. Patients may be suffering with low level depressive symptoms but the fact that they are not actually getting into the trouble that occurs in mania can lead one to think that this situation is all right. There is also concern about using antidepressants because of the risk of making the illness worse (see Qs 3.15 and 6.23). However, long-term but low-level depressive symptoms do need to be searched for and considered.

The first line of treatment is to optimise current medication. If the patient is on long-term treatment such as lithium, there may be leeway to increase this further, provided that side-effects are tolerable and blood levels are not excessive.

The first line of treatment is to optimise current medication. If the patient is on long-term treatment such as lithium, there may be leeway to increase this further, provided that side-effects are tolerable and blood levels are not excessive. If the patient is not on an antidepressant and long-term preventive treatment has been maximised, then look at the effects of previous antidepressants. If they have led to a worsening of the illness through rapid cycling or quick switches into mania then antidepressants should only be used with great caution or not at all. Some antidepressants have a lower propensity for inducing mania and so one of these may be more appropriate (see Table 3.2).

If the patient is not on an antidepressant and long-term preventive treatment has been maximised, then look at the effects of previous antidepressants. If they have led to a worsening of the illness through rapid cycling or quick switches into mania then antidepressants should only be used with great caution or not at all. Some antidepressants have a lower propensity for inducing mania and so one of these may be more appropriate (see Table 3.2). If the patient is taking an antidepressant ensure that this is at a therapeutic dose–just because the symptoms are of a lowish level doesn’t mean the antidepressant should also be at a lowish level. It is worth trying to reach the highest dose tolerated with one antidepressant before considering changing to another.

If the patient is taking an antidepressant ensure that this is at a therapeutic dose–just because the symptoms are of a lowish level doesn’t mean the antidepressant should also be at a lowish level. It is worth trying to reach the highest dose tolerated with one antidepressant before considering changing to another. Combinations of longer term preventive treatments (e.g. lithium with carbamazepine or valproate) should also be considered.

Combinations of longer term preventive treatments (e.g. lithium with carbamazepine or valproate) should also be considered. Finally, consider an alternative such as lamotrigine (see Q 3.4) which is less likely to lead to the complications of switching and rapid cycling.

Finally, consider an alternative such as lamotrigine (see Q 3.4) which is less likely to lead to the complications of switching and rapid cycling.3.15 Do antidepressants trigger mania?

![]() Antidepressants can trigger a manic illness in those who have previously been manic, but only rarely in those who have not previously been manic (see Table 3.2). Antidepressants should not be prescribed to someone who has had a previous episode of mania (even if it was a long time ago) without an additional treatment to prevent mania.

Antidepressants can trigger a manic illness in those who have previously been manic, but only rarely in those who have not previously been manic (see Table 3.2). Antidepressants should not be prescribed to someone who has had a previous episode of mania (even if it was a long time ago) without an additional treatment to prevent mania.

Tricyclic antidepressants are more likely to trigger mania than SSRIs. The use of antidepressants of all types is also associated with rapid cycling (several episodes of mania and depression in quick succession). Patients who have a rapid cycling pattern should not continue to take antidepressants and stopping these drugs can lead to a considerable improvement in the stability of their mood.

Whether it is reasonable to give antidepressants to someone who has only suffered hypomania but not mania in the past is much more uncertain. It is not clear whether antidepressants can lead to mania in someone who has only been hypomanic previously. One trial in this group of patients found that some did become hypomanic again, but did not find that patients became manic for the first time (Amsterdam et al 1998) (see Fig. 3.3)

3.16 What treatment is needed for depression with psychotic symptoms?

It is usually only the most severe depressions that are accompanied by psychotic symptoms. Psychotic depression is a high risk state and the propensity to suicide is very high in this group, and they are more unpredictable. They often need treatment in hospital and a high degree of nursing care, not just for their safety but also because they have difficulty looking after their basic needs, including feeding and washing.

These more extreme depressive states will frequently warrant treatment with ECT (see Q 3.22).

3.17 What is the best treatment for anxiety symptoms in bipolar depression?

Anxiety symptoms occur commonly and often prominently in bipolar depression. They may appear on their own but are more usually part of the depression. The first line of treatment would be to treat the anxiety symptoms as if they are an aspect of depression (see Q 1.14). However, the anxiety symptoms may persist despite antidepressant treatment at a full dose in combination with a mood stabiliser. If there are still prominent depressive symptoms then follow the usual further lines for treating depression (see Qs 3.10 and 6.21). It is worth giving some consideration to the antidepressant being prescribed as MAOIs are thought to be more effective in depression with anxiety.

3.18 How is the risk of suicide judged?

All those suffering from manic depression are at least at moderate risk for suicide–this serious mental illness substantially inflates the risk. It is not justifiable to regard anyone with this diagnosis as at low risk for suicide.

All those suffering from manic depression are at least at moderate risk for suicide–this serious mental illness substantially inflates the risk. It is not justifiable to regard anyone with this diagnosis as at low risk for suicide. The quality of the patient’s life is usually based on having close relationships, employment, financial security and physical health. These aspects of life are adversely affected in those who do commit suicide but are very difficult to change.

The quality of the patient’s life is usually based on having close relationships, employment, financial security and physical health. These aspects of life are adversely affected in those who do commit suicide but are very difficult to change. Older age is a risk factor for suicide in the general population but is less important among manic depressives where suicide occurs across the age range.

Older age is a risk factor for suicide in the general population but is less important among manic depressives where suicide occurs across the age range.3.19 How can suicidal ideas be elicited?

‘Almost everyone who is depressed feels suicidal at times–I was wondering to what extent this has been affecting you?’, followed up by:

‘Almost everyone who is depressed feels suicidal at times–I was wondering to what extent this has been affecting you?’, followed up by: ‘What had you thought you might do?’ (Try to find out if the patient has actually made any plans or done any preparatory acts, e.g. putting a noose in the boot of the car.)

‘What had you thought you might do?’ (Try to find out if the patient has actually made any plans or done any preparatory acts, e.g. putting a noose in the boot of the car.) What does the patient think would be the effect of their suicide on others–from ‘I know I couldn’t, it would kill my mother’ to ‘They would all be better off without me, even my baby–then someone would take proper care of her’.

What does the patient think would be the effect of their suicide on others–from ‘I know I couldn’t, it would kill my mother’ to ‘They would all be better off without me, even my baby–then someone would take proper care of her’. What has prevented them from taking their own life? Sometimes the reasons will be a surprise: ‘I couldn’t stand my ex-wife finally getting the house!’

What has prevented them from taking their own life? Sometimes the reasons will be a surprise: ‘I couldn’t stand my ex-wife finally getting the house!’![]() It is worth bearing in mind that a majority of manic depressives who do kill themselves are not on optimal treatment, although this is often because of poor compliance. Lithium does reduce the rate of suicide, some have claimed even to the level of the general population. Has this patient had the best treatment available, or at least a trial of treatments (including lithium) that are known to be beneficial?

It is worth bearing in mind that a majority of manic depressives who do kill themselves are not on optimal treatment, although this is often because of poor compliance. Lithium does reduce the rate of suicide, some have claimed even to the level of the general population. Has this patient had the best treatment available, or at least a trial of treatments (including lithium) that are known to be beneficial?

3.20 Is psychological treatment for depression useful for bipolars?

Cognitive behaviour therapy: This is the mainstay of psychological treatment for depression and the principles of this can be applied in bipolar depression in a manner similar to the way it is used in unipolar depression (see Q 3.21). The main differences lie in the fact that the symptoms of mania (e.g. optimistic thinking) may be a bad sign rather than a good one.

Cognitive behaviour therapy: This is the mainstay of psychological treatment for depression and the principles of this can be applied in bipolar depression in a manner similar to the way it is used in unipolar depression (see Q 3.21). The main differences lie in the fact that the symptoms of mania (e.g. optimistic thinking) may be a bad sign rather than a good one. Past experiences and relationships: Other psychological approaches focus more on past experiences and relationships. The aim of this is to help patients to understand the patterns of their relationships, what difficulties have emerged and how their attitudes and feelings have contributed to this. A better understanding can lead to an improvement in relationships.

Past experiences and relationships: Other psychological approaches focus more on past experiences and relationships. The aim of this is to help patients to understand the patterns of their relationships, what difficulties have emerged and how their attitudes and feelings have contributed to this. A better understanding can lead to an improvement in relationships. Marital therapy: For those who are currently in a relationship, particularly one that is under strain, a good approach to psychological treatment is one that involves the partner as well. Couple or marital therapy can be a very effective way of mobilising the resources of the couple to improve their relationship and making use of the major asset that comprises a good relationship.

Marital therapy: For those who are currently in a relationship, particularly one that is under strain, a good approach to psychological treatment is one that involves the partner as well. Couple or marital therapy can be a very effective way of mobilising the resources of the couple to improve their relationship and making use of the major asset that comprises a good relationship. Counselling: This is aimed at resolving current practical and emotional problems. Time is given to looking at ways of managing practical problems–for example a young mother looking at what possibilities there might be for childcare to allow some time away from looking after children. However, it is very difficult for those who are more than mildly depressed to make use of this approach because their negative view of themselves and their situation strongly colours their perception of the problems.

Counselling: This is aimed at resolving current practical and emotional problems. Time is given to looking at ways of managing practical problems–for example a young mother looking at what possibilities there might be for childcare to allow some time away from looking after children. However, it is very difficult for those who are more than mildly depressed to make use of this approach because their negative view of themselves and their situation strongly colours their perception of the problems. Education: The most basic form of psychotherapy is education, both about the illness in general and about the particular pattern of illness in that patient. It is only when people are able to recognise how the illness manifests itself in their case that they can really take on productive approaches to taking care of themselves and finding which treatments are helpful. This is vital for everyone who suffers from manic depression.

Education: The most basic form of psychotherapy is education, both about the illness in general and about the particular pattern of illness in that patient. It is only when people are able to recognise how the illness manifests itself in their case that they can really take on productive approaches to taking care of themselves and finding which treatments are helpful. This is vital for everyone who suffers from manic depression.3.21 What is cognitive behaviour therapy?

RECOGNISING AND MANAGING NEGATIVE THINKING

Step 1: Recognising this pattern is the first step in intervening–even a simple self-acknowledgement of what is happening can help to stop the rumination. These thoughts are likely to emerge again as they become so automatic, but if active rumination can be changed to an attempt to interrupt, this can be very helpful. There are usually a number of similar ‘mental grooves’ that make up depressive thinking.

Step 1: Recognising this pattern is the first step in intervening–even a simple self-acknowledgement of what is happening can help to stop the rumination. These thoughts are likely to emerge again as they become so automatic, but if active rumination can be changed to an attempt to interrupt, this can be very helpful. There are usually a number of similar ‘mental grooves’ that make up depressive thinking. Step 2: The next step after recognition is examining the truth of the self-talk. What does ‘I’m useless’ mean? Does this mean that the person can’t do anything at all–not even make someone a cup of tea? Usually the automatic depressive thinking is very extreme and it is not difficult for a therapist to challenge it in this way, and usually patients feel better when this is done in an interview.

Step 2: The next step after recognition is examining the truth of the self-talk. What does ‘I’m useless’ mean? Does this mean that the person can’t do anything at all–not even make someone a cup of tea? Usually the automatic depressive thinking is very extreme and it is not difficult for a therapist to challenge it in this way, and usually patients feel better when this is done in an interview. Step 3: The third step for patients to learn is to challenge their own thinking; psychotherapy techniques aim to get patients to take this on for themselves. Cognitive therapists have a wide variety of techniques to help people manage their thinking more effectively, but it can also be useful for doctors to use this type of approach in discussions with the depressed (see Further reading).

Step 3: The third step for patients to learn is to challenge their own thinking; psychotherapy techniques aim to get patients to take this on for themselves. Cognitive therapists have a wide variety of techniques to help people manage their thinking more effectively, but it can also be useful for doctors to use this type of approach in discussions with the depressed (see Further reading).PROMOTING PRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOURS

Consider also pleasurable activities in which patients had previously been involved and which could be tried out again. Starting with low level activities–a walk in the park with a friend rather than a wild night out on the town–is a sensible place to begin (see also Q 3.36).

3.22 Does ECT have a place in the treatment of manic depression?

A few patients who have had ECT in the past and found it to be the most effective treatment will come and ask for this treatment first line if they become depressed. This would be completely outside some guidelines (e.g. National Institute for Clinical Excellence, see Appendix 1), but it is a request that should be seriously considered as ECT is the quickest and most effective antidepressant treatment.

Occasionally ECT can be used in the treatment of mania or mixed affective states (see Q 4.12).

3.27 Are there any blood tests or other investigations that should be done when someone is depressed?

3.28 What is the best way to talk to someone who is depressed?

There is no best way but there are aspects of the interview that are worth considering. The depressed often need more time than we usually put aside for consultations, they may be retarded and have poor concentration which means that getting them to provide the relevant information can be slow. They are, however, often easy to deal with briefly because their low self-esteem and hopelessness means that they do not want to take up any time as they don’t believe they will be able to get help. The hopelessness of depression can be infectious and there is a need to guard against falling in with this and not following a line of treatment that may be beneficial.

The patient will only be able to take in a small amount of information, so advice needs to be kept simple and should probably be written down as well. It is often helpful to have a friend or relative along as they will be able to recall more from this interview. They can also help to keep a more balanced picture of the meeting than the negative bias that the patient will tend to recall of what has been discussed. Keeping a balance between optimism and realism is difficult, as encouragement should be provided, but unrealistic promises about the benefits of treatment or overoptimistic prognoses for the speed and extent of improvement can backfire later and lead to patients losing confidence in their treatment. Focusing on what someone can do to improve their own symptoms and situation and not just relying on the medication is important (see Q 3.36), particularly in helping to improve self-esteem:

Focusing on the efforts that they have already made and trying to get patients to spell this out can help to get a more realistic view of the current position.

Focusing on the efforts that they have already made and trying to get patients to spell this out can help to get a more realistic view of the current position. Looking at what happened during previous periods of depression and how recovery occurred is useful and realistic in terms of prognosis.

Looking at what happened during previous periods of depression and how recovery occurred is useful and realistic in terms of prognosis. Making plans on an achievable and gradual basis even from a small start–for example having a walk to the post box each day as a beginning on which to build–can discourage unrealistic goals (e.g. walking 5 miles a day, when the post box has not yet been achieved).

Making plans on an achievable and gradual basis even from a small start–for example having a walk to the post box each day as a beginning on which to build–can discourage unrealistic goals (e.g. walking 5 miles a day, when the post box has not yet been achieved). Helping to recognise the circular patterns of thinking and trying to put aside worries even for a short while is helpful.

Helping to recognise the circular patterns of thinking and trying to put aside worries even for a short while is helpful. Letting patients discuss at length the way they are feeling and the thoughts that they are getting can prove counterproductive and many depressed people complain that counselling makes them feel worse if all they do is talk about their feelings and problems and reinforce their own negativity.

Letting patients discuss at length the way they are feeling and the thoughts that they are getting can prove counterproductive and many depressed people complain that counselling makes them feel worse if all they do is talk about their feelings and problems and reinforce their own negativity.Patients will gain confidence if they perceive that their depression is understood–for example by asking about common symptoms that they will have and also understanding that they are likely to be feeling worthless, hopeless and desperate. Accepting that they are likely to have thoughts about death and suicide makes a discussion of these issues much more productive than if they think that you are going to be shocked by these ideas. There are limits to what can be offered but letting patients have a means of contact if they are getting worse–and knowing how quickly they will get a response–can be very helpful.

3.29 What general advice can be given to someone who is depressed?

LIGHT AND SUNLIGHT

Winter depression can be specifically treated with bright light, but many people find the dark winters depressing (see also Q 3.34). It is surprising how much light there is outside on even a dull winter’s day. Encouraging the depressed to get some fresh air and sunlight, even in the winter, may sound very traditional advice but works for some!

3.30 What advice can be given to someone who is sleeping badly?

There are a variety of techniques that people can use to help to get themselves off to sleep, or at least to relax. Virtually everyone who suffers from manic depression will benefit from having one of these strategies available to them. Relaxation techniques (e.g. breathing exercises) are the most basic methods. These can give both physical and mental relaxation; however it can also be helpful to have a specific mental technique to quieten down the thoughts that are crowding round the mind (see Q 3.38). It is generally much easier to learn these techniques when reasonably well rather than when in the grips of depression.

Prescribing a hypnotic is another option, though many are reluctant to use benzodiazepines because for every 10 patients started on them one is likely to continue long term. However, if this is a short-term prescription only then temazepam 10-20 mg is appropriate. The newer sleeping pills such as zopiclone (7.5 mg) are thought to be less likely to lead to dependence but still need to be used with caution.

3.32 When should someone who is depressed be in hospital?

TO HOSPITALISE OR NOT?

If it is possible to provide extra help at home through the local mental health and social services then this would usually be preferable, unless there is a very high suicide risk or it would put an unreasonable burden on the family. The presence of psychosis in depression is a very ominous sign and it is very likely that admission will be needed unless there is an equivalent level of support outside hospital. There is always a substantial suicide risk among the severely or chronically depressed and judging when this is so high as to require monitoring by nursing staff in hospital is a challenge for us all (see Q 3.18). The fact that there is a substantial number of patients who commit suicide during their admission or soon after discharge is testimony to this.

3.33 What advice can be given to relatives of someone who is depressed?

The main advice that can be given to family or friends who are caring for someone with bipolar depression is similar to that given to patients (see Q 3.36). It is very helpful to have a family member in the interview when giving advice to a depressed patient because they have such difficulty concentrating and remembering what has been discussed. The discussion will often turn to the balance between trying to encourage the depressed person but not feeling that you are bullying or nagging them. This is a difficult but important balance to strike. Sometimes it is possible to get the patient to tell their carer what they find most helpful and what they want the family to do when they are finding it difficult to motivate themselves. It is more likely to be acceptable when they have initiated the idea rather than when they are being pushed by the relative.

The other worry of carers is suicide risk and this should be discussed as frankly as possible, recognising that suicidal ideas are very common in depression but trying to help carers to identify when this might be becoming too extreme or dangerous for them to manage safely at home (see Q 3.19).

3.34 What is seasonal affective disorder?

If seasonal affective disorder is related to lack of sunlight then it makes sense to replace this with artificial light (see also Q 2.34). There are several types of artificial light boxes available. However, the principle is for the depressed patient to sit next to a very bright light, usually for an hour in the morning and an hour in the evening. They can read a book or be watching television but need to look at the light frequently while they are doing this. This is actually very restrictive and compliance with the treatment is often poor; however some people particularly like this approach. There are now some ‘light hats’ available which are essentially baseball caps with bulbs in the peak; however, the efficacy of this has not been well proven compared to the light box. The other alternative for getting more light is to have a walk outside as even dull days produce a lot of light and the exercise can also be helpful for depression.

3.35 What advice can be given about work when someone is depressed?

Many people are concerned that returning to work could make them ill again. If there are specific problems and stresses at work then these need to be dealt with and there are situations where it is clear that returning to work is not an option. However, if there has been a good recovery, try to encourage the patient to return to their previous level of function in every arena. It is usually only getting back to work that gives people the confidence that they can do it, and the work itself helps them to rehabilitate. Do discuss with the patient what to say to colleagues at work; if an answer can be prepared beforehand, this can make life much easier (see Q 3.41).

3.37 How can I recognise early that the depression is returning?

Certain symptoms may be particularly important: sleep loss is usually a serious sign and you should not have more than a couple of sleepless nights before you do something about this. It may be well worth having some medication readily available to deal with sleep problems. Other very ominous signs are symptoms of psychosis (e.g. your ideas become very extreme or you experience hallucinations). These symptoms require treatment as soon as they arise and you should not wait to see what happens.

3.41 What do I say to my friends and colleagues about my illness?

‘Thanks for asking. Yes, I’ve been having a difficult time, got very stressed but I’m getting back on my feet now. How have things been in the office?’

‘Thanks for asking. Yes, I’ve been having a difficult time, got very stressed but I’m getting back on my feet now. How have things been in the office?’There are others who are more sympathetic or have had similar experiences, but manic depression is still uncommon so that friends may think that they understand what you have been through when they really don’t. Using words like depression are probably appropriate in this case; however, be wary of talking too much about what has happened as friends may not be as interested as they appear and may also be quite judgemental. Often they will ask what they can do to help and try to have an answer to this, for example: ‘What would be really useful would be if you could let me get on with the work on my own but then help me to check it to make sure that I’m doing OK.’ This type of approach both acknowledges their sympathy and also ensures that what they are doing is helpful but not too intrusive.