Treatment of Allergic Eye Disease

Introduction

SAC is the most prevalent form of ocular allergy and is often accompanied by seasonal allergic rhinitis. Its seasonal incidence is closely tied to the cyclic release of environmental plant-derived airborne allergens. PAC is more likely to occur year-round, though most patients also experience seasonal exacerbations, and is thought to be caused by indoor allergens, such as animal dander and dust mites. Both SAC and PAC can cause significant morbidity, but rarely cause permanent visual impairment. VKC is a less common, self-limited variant of ocular allergy, that can present with unique corneal and conjunctival manifestations, described elsewhere in this text. AKC is a chronic condition associated with atopic dermatitis or eczema, often in individuals with a history of atopy. Both VKC and AKC are primary conjunctival disorders that can cause secondary corneal scarring and therefore, can be vision-threatening. Giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) is a reversible condition, most commonly associated with chronic mechanical irritation from contact lenses, exposed sutures, or prostheses. CAC occurs after sensitization to ocular medications and their preservatives.1

Avoidance

Avoiding known allergen triggers is critical to prevent or ameliorate the symptoms of ocular allergies. Many patients are aware of their allergen triggers, but in some cases allergy testing can be helpful. Possible strategies for avoiding allergens include, staying indoors during high pollen counts, using air conditioners and air filters in the home and car, keeping windows closed, and washing hair and clothes after being outdoors. Patients with perennial allergic conjunctivitis may benefit from covering bedding with plastic covers, removing carpets, and avoiding pets. At a minimum, pets should not be allowed in the bedroom. When eyes itch, the natural response is to rub. The temporary relief of itching achieved from rubbing is negated by a more exuberant inflammatory response.2 Eye rubbing may bring large quantities of allergens in direct contact with the conjunctiva from the hands and may mechanically disrupt cell membranes, resulting in further release of inflammatory mediators.2,3 The inflammation, in turn, may result in an itch – rub cycle that is difficult to break. In addition, chronic eye rubbing has been associated with the development of keratoconus. Encouraging patients to stop rubbing their eyes should be a fundamental goal. Cool artificial tears may provide some relief by diluting both inflammatory mediators and allergens on the ocular surface. Cool compresses and ice packs to the eyelids may reduce swelling and provide some additional relief. For many patients, non-medical treatments alone are not sufficient.1

Medical Therapy

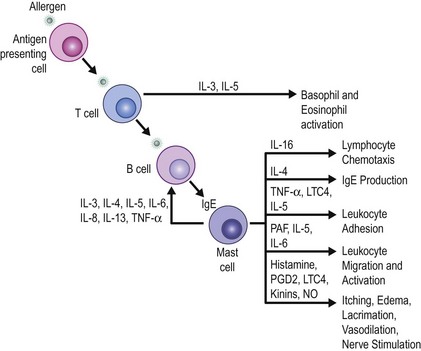

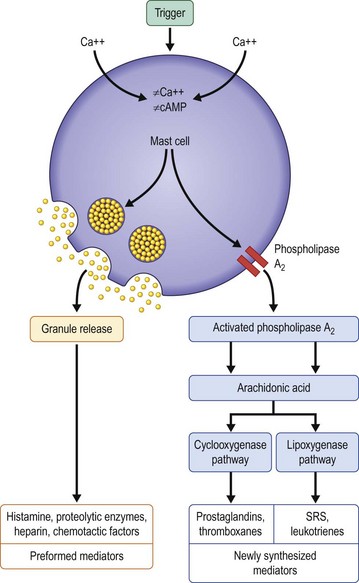

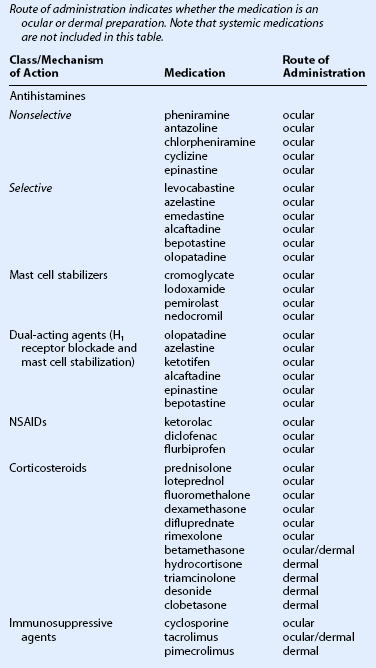

When choosing a medical therapy for allergic conjunctivitis, it is important to remember that the efficacy of an individual medication will vary between patients. As discussed below, each medical therapy targets different mediators in the inflammatory cascade for allergic conjunctivitis (Figs 17.1, 17.2). Selection of an antiallergy medication should be based on the severity, symptoms and projected duration of a patient’s allergic disease. For example, a patient with a severe allergic response may initially benefit from a topical corticosteroid, while a patient with moderate symptoms from complex allergies or who requires extended treatment, may do well with mast cell stabilizers or dual-action agents (mast cell stabilizer/antihistamine). Topical medications are listed in Table 17.1.

Table 17.1

Topical Medications for the Treatment of Allergic Conjunctivitis

(From Mishra GP, Tamboli V, Jwala J, et al. Recent patents and emerging therapeutics in the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2011;5:26–36.)

Vasoconstrictors

Over-the-counter topical decongestants containing vasoconstrictors with or without antihistamines are generally well tolerated and effective for patients with mild allergic symptoms.4,5 Although the antihistamine component is weak, the vasoconstrictor component is very effective in reducing conjunctival hyperemia via alpha adrenoceptor stimulation. In the United States, either pheniramine or antazoline, the common antihistamines, is combined with naphazoline, a vasoconstrictor. Using these drops over time may result in tachyphylaxis, requiring patients to use the drops more frequently to obtain the same vasoconstrictor effect. Furthermore, discontinuation of vasoconstricting eyedrops may result in rebound hyperemia.6 Depending on the underlying condition, artificial tears, corticosteroid drops, or long-term therapy with mast cell stabilizers and/or immunotherapy may help alleviate dependence on the vasoconstricting eyedrops.6 Due to their mydriatic effect, topical decongestants are contraindicated in patients with narrow angles.

Antihistamines

Second-generation antihistamines do not cross the blood – brain barrier. They selectively block peripheral H1 receptors, reducing the occurrence of sedation while still effectively treating allergic symptoms. These more potent topical antihistamines include levocabastine hydrochloride 0.05% and emedastine difumarate 0.05%. Most of the recent antihistamines have also been shown to have some mast cell stabilizing properties as well. Most topical antihistamines have a rapid onset of action, but have a short duration of action, requiring up to four times daily dosing. Selective antihistamines with mast cell stabilizing properties, such as olopatadine, azelastine, ketotifen, alcaftadine, epinastine, and bepotastine, have been shown to have a rapid onset but a longer duration of action when compared to the other topical antihistamines, lasting up to 16 hours.7–10 Because of the improved efficacy of combined antihistamine/mast cell stabilizers, the pure antihistamine drops have largely been replaced by combination drops.

Systemic therapy with oral antihistamines (diphenhydramine, carbinoxamine, clemastine, chlorpheniramine, brompheniramine, oxatomide, cetirizine, levocetirizine, loratadine, desloratidine, ketotifen, and fexofenadine) may be beneficial for perennial, vernal, or atopic allergic keratoconjunctivitis, given the chronicity of the disease and the potential for patients to become sensitized to preservatives in some commercial topical preparations. However, oral antihistamines are seldom used to treat isolated seasonal or perennial allergic conjunctivitis, but are frequently used to treat systemic allergy. They should be used with caution in patients with cardiac arrhythmias, or in combination with erythromycin, ketoconazole, itraconazole and troleandomycin. These medications may improve systemic symptoms, but ocular symptoms may worsen. Symptoms of dry eye may be induced or compounded by the propensity of antihistamines to reduce tear production. Topical antihistamines have muscarinic binding properties which, in theory, may also cause or worsen dry eye syndrome. The data on their effect on tear production are conflicting.11 In general, there is little clinical evidence that topical antihistamines induce dryness. When oral antihistamines are needed to treat rhinitis, the addition of a topical antihistamine may help the ocular symptoms.

Mast Cell Stabilizers

Given that these medications inhibit the release of histamine rather than block histamine receptors, they are better at preventing than treating allergic signs and symptoms. Their effects may not be seen until 2 to 5 days after initiation of therapy, while their maximum benefit is achieved 15 days after initiating therapy. Therefore, if patients have allergic symptoms during a defined season, they should begin these medications about 2 weeks prior to their allergy season and continue throughout the entire season. Mast cell stabilizers represent the mainstay of therapy for vernal and atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Nedocromil, originally thought to be just a mast cell stabilizing agent, is recognized to have multiple actions resulting in rapid relief of symptoms. These actions include antihistaminic (H1 antagonist) effects, reduction of ICAM-1 expression, and inhibitory effects on eosinophils and neutrophils.12

Numerous studies have demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of cromolyn sodium, nedocromil, lodoxamide, and pemirolast, in treating signs and symptoms of vernal and seasonal allergic conjunctivitis.13–21 When comparing the older agents, lodoxamide is about 2500 times more potent than sodium cromoglycate in an animal model, although their efficacy in controlling the symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis is similar.22 A long-term comparison of nedocromil versus cromolyn sodium found that nedocromil 2% produced a more rapid and marked improvement in symptoms over cromolyn 2% and decreased the need for steroid rescue.23 Lodoxamide 0.1% may have additional benefits over cromolyn sodium because it has been found to also have potential antieosinophil action.16,24

Additional studies suggest that mast cell stabilizers may act through other mechanisms. Cromolyn sodium reportedly inhibits the chemotaxis, activation, degranulation, and cytotoxicity of neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes.16,25 Lodoxamide and cromolyn sodium may also have effects on Th2 cells, which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of VKC.26 In some patients, mast cell stabilizing drops may be more effective for chronic therapy than dual-acting agents (antihistamine/mast cell stabilizing agents).

Dual-Acting Agents

The dual-acting medications, including olopatadine hydrochloride 0.1% and 0.2%, azelastine hydrochloride 0.05%, ketotifen fumarate 0.025% (available over the counter), alcaftadine 0.25%, bepotastine 1.5%, and epinastine hydrochloride 0.05%, have antihistamine and mast cell stabilizing properties. Most of these drugs have additional modes of action, including eosinophil and basophil inhibition.27,28 These medications are usually effective for the treatment and prevention of signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis.29–31 Olopatadine 0.2% and alcaftadine are the only antiallergy eyedrops approved for once-daily dosing. These dual-action medications are appropriate choices for patients with acute seasonal exacerbations, as well as those with chronic perennial symptoms; they are the mainstay of therapy for the majority of patients with allergic conjunctivitis.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Ketorolac tromethamine 0.5%, diclofenac, and flurbiprofen are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents which decrease the activity of cyclooxygenase, an enzyme responsible for arachidonic acid metabolism. The inhibition of cyclooxygenase, in turn, reduces prostaglandin production, most notably the highly pruritic PGE2 and PGI2.32 These drugs have been shown to reduce itching, ICAM-1 expression, and tryptase levels in tears associated with ocular allergy.33–35 Topical ketorolac tromethamine, the only approved nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug for managing ocular allergies, has been shown to provide relief of the signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis.36,37 Some patients have transient stinging upon instillation. The newer agents discussed above have largely replaced the topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents.

Signs and symptoms of VKC have been reported to improve with the addition of oral aspirin (1.5 g–4.0 g per day), although routine administration at these high doses could produce serious side effects, especially given that many VKC patients are children.38,39

Corticosteroids

Topical corticosterioids, including prednisolone, loteprednol, dexamethasone, fluorometholone, and rimexolone, are highly effective for the treatment of ocular allergy because they block most allergic inflammatory cascades (including the late-phase mediators). Corticosteroids diminish the signs and symptoms of ocular allergy by stabilizing capillary permeability, decreasing the influx of inflammatory cells, and inhibiting the activation and degranulation of inflammatory cells.40 Intranasal corticosteroids, when used to treat allergic rhinitis, may also improve concurrent ocular symptoms.41–43 Corticosteroids are particularly helpful in the treatment of VKC and AKC but are less often used for GPC or SAC. Given their propensity to induce cataracts, elevate intraocular pressure in susceptible individuals and potentiate ocular infections, their judicious use is indicated.44

It may be necessary to use corticosteroids in SAC for short periods, if the allergic response is severe and conservative therapy has failed. Loteprednol, an ester corticosteroid which is metabolized in the aqueous humor, is effective in treating seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. In a recent retrospective study, loteprednol 0.2% was well tolerated with no reports of adverse reactions in patients treated for SAC or PAC for at least 12 months.45

Moderate to severe cases of VKC or AKC that are unresponsive to mast cell stabilizers and antihistamines, may necessitate the short-term use of topical corticosteroids. Corneal involvement at any stage warrants the consideration of corticosteroid therapy. Bonini and colleagues reported that 85% of patients in their long-term cohort of 195 VKC patients, required steroids at some point during the course of the disease.46

Allansmith found that ‘pulse’ therapy with topical dexamethasone (1%) given every 2 hours, eight times daily and gradually tapered over days to weeks, to be effective for breakthrough attacks of VKC inflammation.47

In the absence of corneal involvement, low-absorption corticosteroids, such as fluorometholone, loteprednol, and rimexolone, should be tried first. Dose and frequency are determined based on the level of inflammation, with a gradual taper occurring over 2 weeks. Only after first-line therapy fails should more potent agents, such as prednisolone, dexamethasone, or betamethasone be considered.48 Supratarsal injection of short- or intermediate-acting corticosteroids has also been reported to confer relief in severe VKC.49

Long-term maintenance, topical steroid therapy should be avoided given the potential complications, including glaucoma, formation of cataracts, and increased susceptibility to infections. Corticosteroid therapy has been associated with 2% to 7% of VKC patients developing glaucoma and 14% developing cataracts.46,50,51 If corticosteroids are necessary, patients should be given the lowest concentration for the shortest duration with appropriate follow-up.

Additional Treatments for VKC and AKC

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine, an immunosuppressive drug commonly used to prevent organ-graft rejection, has demonstrated efficacy in controlling ocular inflammation. Cyclosporine works primarily by binding to the cytosolic protein cyclophilin and blocking Th2 lymphocyte proliferation and IL-2 production.52 It also inhibits histamine release from mast cells and basophils and reduces IL-5 production, which may limit the infiltration of eosinophils into the conjunctiva.53,54 Clinically, cyclosporine A administration results in a reduction in total T cells, a normalization of the CD4 : CD8 ratio, a decrease in T-cell activation, and a reduction in T-cell cytokine expression, especially IL-2 and IFN. Cyclosporine A has been shown to have an immunomodulatory effect in atopic and vernal keratoconjunctivitis.55–57 Leonardi and colleagues suggest that cyclosporine shows particular effectiveness in VKC by reducing conjunctival fibroblast proliferation and IL-1b production.58

Cyclosporine 1% to 2% ophthalmic emulsions in olive, maize, or castor oil have been shown to be effective in the treatment of VKC and AKC.59–66 It has been demonstrated that cyclosporine 2%, used four times daily over 2 weeks, significantly decreases signs and symptoms in VKC patients and that it was effective in decreasing dependence of steroids in patients with AKC.67,68 Several groups have examined the effectiveness of cyclosporine at concentrations as low as 0.05%, but results at these levels have been equivocal. Spadavecchia and colleagues suggest that 1% may be the lower bound for effective dosage as demonstrated in their cohort of school-age children.69 Leonardi and colleagues found cyclosporine to have a significant steroid sparing effect, allowing VKC to be controlled with mast cell stabilizers alone.70 Unlike corticosteroids, cyclosporine has not been associated with lens changes or increases in intraocular pressure.71,72 However, many patients complain of burning and irritation associated with current formulations. Other adverse events, such as bacterial or viral infections, are rare.

Tacrolimus and Pimecrolimus

Tacrolimus (FK506) is an immunosuppressant drug used for prevention of organ transplant rejection. It inhibits calcineurin and stops the synthesis and release of cytokines from T lymphocytes, preventing T-lymphocyte activation. Multiple recent studies have investigated topical tacrolimus 0.005–0.03% as a treatment for both vernal and atopic conjunctivitis with good results.73–82 The studies have demonstrated efficacy comparable to that of corticosteroids for clinical signs and symptoms, as well as decrease in conjunctival inflammatory markers, such as eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes.80 Tacrolimus therapy alone has been demonstrated to treat the symptoms and signs of VKC and AKC, such as burning, tearing, photophobia, injection, pain, and itching, as well as regression of GPC, resolution of shield ulcers, and healing of corneal epithelial disease.75 It appears to be successful in the treatment AKC and VKC, even in patients who have been refractory to treatment with systemic and/or topical steroids, antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers, cyclosporine A, and even surgical resection/cryopexy of GPC.74 There have not been any demonstrated adverse effects, except for burning upon instillation. Tacrolimus does not appear to elevate intraocular pressure; therefore it may be a good alternative to treatment with corticosteroids, especially for patients who are steroid responders.76,81 Another calcineurin inhibitor, pimecrolimus, is more selective than tacrolimus and can also be used safely as an ointment for periocular atopic dermatitis. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus ointment can be applied to the lid skin safely for relief of periocular atopic dermatitis, without the side effects of corticosteroids, such as skin atrophy, elevation of intraocular pressure, and cataract formation.

Systemic tacrolimus has been investigated for treatment of VKC or AKC with success, but with greater potential for adverse effects due to systemic immunosupression.82

Other Treatments

Agents that oppose leukotriene action are considered to be important in asthma and other atopic diseases, which may have steroid-independent components. These agents can be used alongside steroids and might allow the reduction of steroid use. Montelukast is a leukotriene receptor antagonist that has demonstrated high affinity, binding to the leukotriene receptor.83 Clinical studies in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis indicated that while symptoms of allergic rhinitis were improved with montelukast, there was no significant difference in ocular symptoms between montelukast and placebo.84 However, montelukast has been demonstrated to be effective in atopic dermatitis, especially of the face, leading to alleviation of pruritus and atopic skin changes.83

Some patients experience relief when their eyes are closed, thus making occlusive therapies (patching, occlusive goggles or a tarsorrhaphy) helpful in some situations, probably by minimizing contact with airborne allergens.85 While contact lens wear may also help limit exposure to airborne allergens, the presence of papillae on the tarsal conjunctiva can make contact lens wear uncomfortable. Additionally, the contact lenses themselves can worsen symptoms of ocular allergies, as discussed below, so this strategy is not routinely recommended.

Surgical Treatment

For large symptomatic papillae, conjunctival transposition or autografts have been performed with some effect.86 Cryotherapy of the tarsal conjunctiva often provides temporary relief, possibly by decreasing the number of inflammatory cells and reducing the inflammatory mediators released; however, the papillae and symptoms usually return. Bonini and colleagues have noted that cryogenic surgery performed to reduce papillary excrescences, may result in a pemphigoid-like appearance throughout the conjunctiva.46 Belfair and colleagues have described the use of CO2 laser in removing giant papillae in refractory VKC.87,88 However, the long-term effectiveness of this modality is unclear. In general, conjunctival surgery is rarely required and should be avoided.

Surgical debridement and superficial keratectomy can aid in the re-epithelialization of the cornea.89 Daily debridement of the ulcer may promote more rapid healing. One study demonstrated rapid re-epithelialization of three central corneal lesions from VKC, that were treated with excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy. This was performed after active inflammation was controlled and the inflammatory plaque overlying the shield ulcer was removed.90

There have also been multiple reports of successful management of shield ulcers with use of amniotic membrane transplantation, either alone or in combination with cryotherapy of GPC, or prior debridement of the ulcer.91–93

Cameron has proposed a classification system for shield ulcers based on their clinical characteristics, response to treatment, and complications. Grade 1 ulcers had a clear base, responded favorably to medical treatment, and re-epithelialized with minimal scarring. Grade 2 ulcers had visible inflammatory debris in the base, responded poorly to medical therapy alone, and demonstrated delayed re-epithelialization with complications, such as bacterial keratitis. Grade 2 patients showed dramatic response to scraping the base of the ulcer, with re-epithelialization occurring by 1 week. Grade 3 ulcers had elevated plaque formation and responded best to surgical therapy.88 Solomon and colleagues have also reported successful re-epithelialization of the cornea, after surgical scraping of vernal plaques in patients who had been nonresponsive to maximal medical therapy.94 Sridhar and colleagues demonstrated additional benefits in combining amniotic membrane grafting, with surgical debridement in a small group of VKC patients.93 Sangwan and colleagues suggest that limbal stem cell transplantation may also have promise in severe cases of VKC.95

Additional Treatments for GPC

Contact lens wearers often do not want to discontinue wearing their lenses, despite having symptomatic GPC. After insertion, contact lenses become coated with a biofilm that can act as a base for antigen deposition and trigger GPC. Patients should maintain meticulous contact lens hygiene or switch to a daily disposable type of contact lens.1 Mechanical removal of mucus and protein deposits from the lens surface by rubbing the contact lens can reduce the likelihood of irritation. Use of hydrogen peroxide-based contact lens cleaning solutions can be helpful as well. Similarly, regular cleaning of ocular prostheses can reduce mucus and protein build-up that can precipitate GPC.

Theoretically, when contact lenses are worn while eyedrops are used, the pharmacokinetics of the drug’s active ingredient and preservative can be altered, allowing for prolonged ocular exposure to these chemicals.96 Thus, putting in contacts at least 20 minutes after drop instillation is recommended. Allergic conjunctivitis can adversely affect tear film stability, which may be why patients with a history of ocular allergy often have contact-lens-related discomfort.4,97

New and Experimental Treatment Modalities

New therapies are being investigated which may be more effective and have safer side effect profiles than current treatment modalities.4 Several patents filed in recent years aim to devise new strategies to treat ocular allergies. Whether these strategies prove to be clinically useful remains to be seen. Large-scale clinical studies have not yet been performed, and therefore, the use of the treatments listed below cannot be recommended at this time. The strategies below are listed for information only.

Yedger filed a patent describing use of lipid-conjugated peptides to treat conjunctivitis by inhibiting phospholipase A2.98 Phospholipase A2 is an enzyme that catalyzes the breakdown of cell membrane phospholipids, leading to production of inflammatory mediators. By inhibiting phospholipase A2, the inventors report reduction in levels of ocular inflammatory mediators and reduction of corneal opacification. Kato and colleagues have reported on a novel selective glucocorticoid receptor agonist, ZK209614, which compared favorably with betamethasone in reducing conjunctival edema in rat and feline models of experimental allergic conjunctivitis.98 While betamethasone caused steroid-induced elevation of intraocular pressure, ZK209614 did not cause a steroid response. Topical chlorogenic acid and glucosamine are being investigated for their inhibitory effects on transglutaminase. In a guinea pig model, chlorogenic acid was found to decrease conjunctival hyperemia and edema.98 Cyclic AMP (cAMP) is a key cytokine regulating activity of neutrophils, eosinophils, and mast cells. Drugs which inhibit phosphodiesterase IV (PDE IV) dependent hydrolysis of cAMP are being investigated for their effects on suppressing activation of the inflammatory cascade. Toll-like receptors (TLR) have been identified on mast cells and circulating leukocytes, regulating the Th1:Th2 balance that can lead to allergic disease. Novel compounds which inhibit TLR and help to down-regulate this pathway are being investigated. Small interfering RNA aimed at blocking various targets in the intracellular mast cell signal transduction cascade are being studied.98 Inhibitory molecules, targeting histamine H4 receptors and Janus protein kinase-3 (JAK-3) are other areas of research. Monoclonal antibodies against the eotaxin receptor are being studied and may limit recruitment of eosinophils to the ocular surface. Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) is an effective hyposensitization treatment for allergic rhinitis, and its use for reducing subjective symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis, was the subject of a recent Cochrane Review meta-analysis of nearly 4000 participants with allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis. The study found that SLIT is moderately effective in reducing ocular allergy symptom scores.99

References

1. Rothman, JS, Raizman, MB, Friedlander, MH. Seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis. In Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds.: Cornea, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2011.

2. Greiner, JV, Peace, DG, Baird, RS, et al. Effects of eye rubbing on the conjunctiva as a model of ocular inflammation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100:45–50.

3. Raizman, MB, Rothman, JS, Maroun, F, et al. Effect of eye rubbing on signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis in cat-sensitive individuals. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:2158–2161.

4. Greiner, JV, Udell, IJ. A comparison of the clinical efficacy of pheniramine solution and olopatadine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution in the conjunctival allergen challenge model. Clin Ther. 2005;275:468–577.

5. Abelson, MB, Allansmith, MR, Friedlander, MH. Effects of topically applied ocular decongestant and antihistamine. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90:254–257.

6. Spector, SL, Raizman, MB. Conjunctivitis medicamentosa. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994;94:134–136.

7. Albietz, JM, Lenton, LM. Management of the ocular surface and tear film before, during, and after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Sur. 2004;20:62–71.

8. Moss, SE, Klein, R, Klein, BE. Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1264–1268.

9. Williams, JI, Kennedy, KS, Gow, JA, et al. Prolonged effectiveness of bepotastine besilate ophthalmic solution for the treatment of ocular symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2011;27:385–393.

10. Torkildsen, G, Shedden, A. The safety and efficacy of alcaftadine 0.25% ophthalmic solution for the prevention of itching associated with allergic conjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:623–631.

11. Lekhanont, K, Park, CY, Combs, JC, et al. Effect of topical olopatadine and epinastine in the botulinum toxin B-induced mouse model of dry eye. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23:83–88.

12. Corin, RE. Nedocromil sodium: a review of the evidence for adual mechanism of action. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:461–468.

13. Foster, CS. Evaluation of topical cromolyn sodium in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:194–201.

14. Abelson, MB, Berdy, GJ, Mundorf, T, et al. Pemirolast potassium 0.1% ophthalmic solution is an effective treatment for allergic conjunctivitis: a pooled analysis of two prospective, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, phase III studies. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2002;18:475–488.

15. Bonini, S, Barney, NP, Schiavone, M, et al. Effectiveness of nedocromil sodium 2% eyedrops on clinical symptoms and tear fluid cytology of patients with vernal conjunctivitis. Eye. 1992;6:648–652.

16. Bonini, S, Schiavone, M, Bonini, S, et al. Efficacy of lodoxamide eye drops on mast cells and eosinophils after allergen challenge in allergic conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:849–853.

17. Foster, CS. Evaluation of topical cromolyn sodium in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:194–201.

18. Blumenthal, M, Casale, T, Dockhorn, R, et al. Efficacy and safety of nedocromil sodium ophthalmic solution in the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113:56–63.

19. El Hennawi, M. A double blind placebo controlled group comparative study of ophthalmic sodium cromoglycate and nedocromil sodium in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:365–369.

20. Kjellman, NI, Stevens, MT. Clinical experience with Tilavist: an overview of efficacy and safety. Allergy. 1995;50:14–22.

21. Stockwell, A, Easty, DL. Group comparative trial of 2% nedocromil sodium with placebo in the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1994;4:12–23.

22. Johnson, HG, White, GJ. Development of new antiallergic drugs (cromolyn sodium, lodoxamide tromethamine). What is the role of cholinergic stimulation in the biphasic dose response? Monogr Allergy. 1979;14:299–306.

23. Verin, PH, Dicker, ID, Mortemousque, B. Nedocromil sodium eye drops are more effective than sodium cromoglycate eye drops for the long-term management of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:529–536.

24. Caldwell, DR, Verin, P, Hartwich-Young, R, et al. Efficacy and safety of lodoxamide 0.1% vs. cromolyn sodium 4% in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113:632–637.

25. Kay, AB, Walsh, GM, Moqbel, R, et al. Disodium cromoglycate inhibits activation of human inflammatory cells in vitro. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;80:1–8.

26. Avunduk, AM, Avunduk, MC, Kapicioglu, Z, et al. Mechanisms and comparison of anti-allergic efficacy of topical lodoxamide and cromolyn sodium treatment in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1333–1337.

27. Hasala, H, Malm-Erjefält, M, Erjefält, J, et al. Ketotifen induces primary necrosis of human eosinophils. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:318–327.

28. Randley, BW, Sedgwick, J. The effect of azelastine on neutrophil and eosinophil generation of superoxide. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;83:400–405.

29. Whitcup, SM, Bradford, R, Lue, J, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of ophthalmic epinastine: a randomized, double-masked, parallel-group, active and vehicle-controlled environmental trial in patients with seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Clin Ther. 2004;26:29–34.

30. Greiner, JV, Michaelson, C, McWhirter, CL, et al. Single dose of ketotifen fumarate. 025% vs 2 weeks of cromolyn sodium 4% for allergic conjunctivitis. Adv Ther. 2002;19:185–193.

31. Spangler, DL, Bensch, G, Berdy, GJ. Evaluation of the efficacy of olopatadine hydrochloride 0.1% ophthalmic solution and azelastine hydrochloride 0.05% ophthalmic solution in the conjunctival allergen challenge model. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1272–1280.

32. Woodward, DF, Nieves, AL, Hawley, SB, et al. The pruritogenic and inflammatory effects of prostanoids in the conjunctiva. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1995;11:339–347.

33. Tinkelman, DG, Rupp, G, Kaufman, H, et al. Double-masked, paired comparison clinical study of ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% ophthalmic solution compared with placebo eyedrops in the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38:133–140.

34. Ballas, Z, Blumenthal, M, Tinkelman, DG, et al. Clinical evaluation of ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% ophthalmic solution for the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38:141–148.

35. Leonardi, A, Busato, F, Fregona, IA, et al. Anti-inflammatory and antiallergic effects of ketorolac tromethamine in the conjunctival provocation model. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1228–1232.

36. Raizman, MB. Results of a survey of patients with ocular allergy treated with topical ketorolac tromethamine. Clin Ther. 1995;17:882–890.

37. Donshik, PC, Pearlman, D, Pinnas, J, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% and levocabastine 0.05%: a multicenter comparison in patients with seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Adv Ther. 2000;17:94–102.

38. Abelson, MB, Butrus, SI, Weston, JH. Aspirin therapy in vernal conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;95:502–505.

39. Chaudhary, KP. Evaluation of combined systemic aspirin and cromolyn sodium in intractable vernal catarrh. Ann Ophthalmol. 1990;22:314–318.

40. Abelson, MB, Schaefer, K. Conjunctivitis of allergic origin: immunologic mechanisms and current approaches to therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38:115–132.

41. Bernstein, DI, Levy, AL, Hampel, FC, et al. Treatment with intranasal fluticasone propionate significantly improves ocular symptoms in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:952–957.

42. Hong, J, Bielory, B, Rosenberg, JL. Efficacy of intranasal corticosteroids for the ocular symptoms of allergic rhinitis: A systematic review. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:22–35.

43. Bielory, L, Chun, Y, Bielory, BP, et al. Impact of mometasone furoate nasal spray on individual ocular symptoms of allergic rhinitis: a meta-analysis. Allergy. 2011;66:686–693.

44. Friedlaender, MH. Corticosteroid therapy of ocular inflammation. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1983;23:175–182.

45. Ilyas, H, Slonim, CB, Braswell, GR, et al. Long-term safety of loteprednol etabonate 0.2% in the treatment of seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis. Eye Contact Lens. 2004;30:10–13.

46. Bonini, S, Bonini, S, Lambiase, A, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis revisited: a case series of 195 patients with long-term follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1157–1163.

47. Allansmith, MR, Vernal conjunctivitis. Duane’s clinical ophthalmology, vol. 4. JB Lippincott: Philadelphia, 1992.

48. Leonardi, A. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: pathogenesis and treatment. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2002;21:319–339.

49. Holsclaw, DS, Whitcher, JP, Wong, IG, et al. Supratarsal injection of corticosteroid in the treatment of refractory vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:243–249.

50. Leonardi, A, Busca, F, Motterle, L, et al. Case series of 406 vernal keratoconjunctivitis patients: a demographic and epidemiological study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:406–410.

51. Tabbara, KF. Ocular complications of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1999;34:88–92.

52. Lightman, S. Therapeutic considerations: symptoms, cells and mediators. Allergy. 1995;50(Suppl. 21):10–13. [discussion: 34–38].

53. Tabbara, KF. Ocular complications of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1999;34:88–92.

54. Sperr, WR, Agis, H, Czerwenka, K, et al. Effects of cyclosporine A and FK-506 on stem cell factor-induced histamine secretion and growth of human mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:389–399.

55. Whitcup, SM, Chan, CC, Luyo, DA, et al. Topical cyclosporine inhibits mast cell-mediated conjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2686–2693.

56. Hingorani, M, Calder, VL, Buckley, RJ, et al. The immunomodulatory effect of topical cyclosporine A in atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:392–399.

57. Leonardi, A, Borghesan, F, DePaoli, M, et al. Procollagens and inflammatory cytokine concentrations in tarsal and limbal vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Exp Eye Res. 1998;67:105–112.

58. Leonardi, A, DeFranchis, G, Fregona, IA, et al. Effects of cyclosporine A on human conjunctival fibroblasts. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1512–1517.

59. BenEzra, D, Pe’er, J, Brodsky, M, et al. Cyclosporine eyedrops for the treatment of severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;101:278–282.

60. Bleik, JH, Tabbara, KF. Topical cyclosporine in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1679–1684.

61. Holland, EJ, Olsen, TW, Ketcham, JM, et al. Topical cyclosporine A in the treatment of anterior segment inflammatory disease. Cornea. 1993;12:413–419.

62. Kaan, G, Ozden, O. Therapeutic use of topical cyclosporine. Ann Ophthalmol. 1993;25:182–186.

63. Kiliç, A, Gürler, B. Topical 2% cyclosporine A in preservative-free artificial tears for the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006;41:693–698.

64. Pucci, N, Novembre, E, Cianferoni, A, et al. Efficacy and safety of cyclosporine eyedrops in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:298–303.

65. Secchi, AG, Tognon, MS, Leonardi, A. Topical use of cyclosporine in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110:641–645.

66. Pucci, N, Caputo, R, Mori, F, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of topical cyclosporine in 156 children with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010;23:865–871.

67. Hingorani, M, Moodaley, L, Calder, VL, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topical cyclosporine A in steroid-dependent atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1715–1720.

68. Lambiase, A, Leonardi, A, Sacchetti, M, et al. Topical cyclosporine prevents seasonal recurrences of vernal keratoconjunctivitis in a randomized, double-masked, controlled 2-year study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:896–897.

69. Spadavecchia, L, Fanelli, P, Tesse, R, et al. Efficacy of 1.25% and 1% topical cyclosporine in the treatment of severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006;17:527–532.

70. Leonardi, A, Borghesan, F, Faggian, D, et al. Eosinophil cationic protein in tears of normal subjects and patients affected by vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Allergy. 1995;50:610–613.

71. Pucci, N, Novembre, E, Cianferoni, A, et al. Efficacy and safety of cyclosporine eyedrops in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:298–303.

72. Perry, HD, Donnenfeld, ED, Kanellopoulos, AJ, et al. Topical cyclosporine A in the management of postkeratoplasty glaucoma. Cornea. 1997;16:284–288.

73. Kheirkhah, A, Zavareh, MK, Farzbod, F, et al. Topical 0.005% tacrolimus eye drop for refractory vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eye. 2011;25:872–880.

74. Garcia, DP, Alperte, JI, Cristobal, JA, et al. Topical tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of intractable atopic keratoconjunctivitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cornea. 2011;30:462–465.

75. Tam, PM, Young, AL, Cheng, LL, et al. Topical tacrolimus 0.03% monotherapy for vernal keratoconjunctivitis – case series. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:1405–1406.

76. Remitz, A, Virtanen, HM, Reitamo, S, et al. Tacrolimus ointment in atopic blepharoconjunctivitis does not seem to elevate intraocular pressure. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:295–296.

77. Attas-Fox, L, Barkana, Y, Iskhakov, V, et al. Topical tacrolimus 0.03% ointment for intractable allergic conjunctivitis: an open-lable pilot study. Curr Eye Res. 2008;33:545–549.

78. Kymionis, GD, Goldman, D, Ide, T, et al. Tacrolimus ointment 0.03% in the eye for treatment of giant papillary conjunctivitis. Cornea. 2008;27:228–229.

79. Miyazaki, D, Tominaga, T, Kakimaru-Hasegawa, A, et al. Therapeutic effects of tacrolimus ointment for refractory ocular surface inflammatory diseases. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:988–992.

80. Virtanen, HM, Reitamo, S, Kari, M, et al. Effect of 0.03% tacrolimus ointment on conjunctival cytology in patients with severe atopic blepharoconjunctivitis: a retrospective study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:693–695.

81. Nivenius, E, Van der Ploeg, I, Jung, K, et al. Tacrolimus ointment vs. steroid ointment for eyelid dermatitis in patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Eye. 2007;21:968–975.

82. Anzaar, F, Gallagher, MJ, Bhat, P, et al. Use of systemic T-lymphocyte signal transduction inhibitors in the treatment of atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2011;27:884–888.

83. Kägi, MK. Leukotriene receptor antagonists – a novel therapeutic approach in atopic dermatitis? Dermatology. 2001;203:280–283.

84. Ashrafzadeh, A, Raizman, MB. New modalities in the treatment of ocular allergy. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2003;43:105–110. [Winter].

85. Jun, J, Bielory, L, Raizman, MB. Vernal conjunctivitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:59–82.

86. Nishiwaki-Dantas, MC, Dantas, PE, Pezzutti, S, et al. Surgical resection of giant papillae and autologous conjunctival graft in patients with severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis and giant papillae. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;16:438–442.

87. Belfair, N, Monos, T, Levy, J, et al. Removal of giant vernal papillae by CO2 laser. Can J Ophthalmol. 2005;40:472–476.

88. Cameron, JA. Shield ulcers and plaques of the cornea in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:985–993.

89. Ozbek, Z, Burakgazi, AZ, Rapuano, CJ, et al. Rapid healing of vernal shield ulcer after surgical debridement: a case report. Cornea. 2006;25:472–473.

90. Cameron, JA, Antonios, SR, Badr, IA. Excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy for shield ulcers and corneal plaques in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. J Refract Surg. 1995;11:31–35.

91. Rouher, N, Pilon, F, Dalens, H, et al. Implantation of preserved human amniotic membrane for the treatment of shield ulcers and persistent corneal epithelial defects in chronic allergic conjunctivitis. J Fr Ophthalmol. 2004;27:1091–1097.

92. Chandra, A, Maurya, OP, Reddy, B, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation in ocular surface disorders. J Indian Med Assoc. 2005;103:364–366.

93. Sridhar, MS, Sangwan, VS, Bansal, AK, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation in the management of shield ulcers of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1218–1222.

94. Solomon, A, Zamir, E, Levartovsky, S, et al. Surgical management of corneal plaques in vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a clinicopathologic study. Cornea. 2004;23:608–612.

95. Sangwan, VS, Murthy, SI, Vemuganti, GK, et al. Cultivated corneal epithelial transplantation for severe ocular surface disease in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2005;24:426–430.

96. Jain, MR. Drug delivery through soft contact lenses. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:150–154.

97. Suzuki, S, Goto, E, Dogru, M, et al. Tear film lipid layer alterations in allergic conjunctivitis. Cornea. 2006;25:277–278.

98. Mishra, GP, Tamboli, V, Jwala, J, et al. Recent patents and emerging therapeutics in the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis. Recent Pat. Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2011;5:26–36.

99. Calderon, MA, Penagos, M, Sheikh, A, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy for treating allergic conjunctivitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6, 2011.