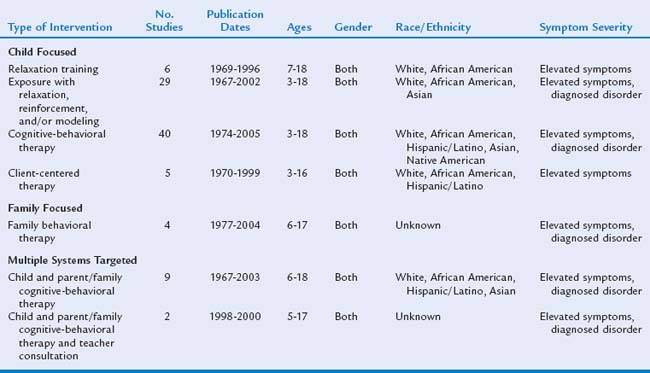

CHAPTER 8 Treatment and Management

8A. The Interdisciplinary Team Approach

In this chapter, we discuss the interdisciplinary team approach within health care and the field of developmental disabilities. We cover such topics as the history of interdisciplinary teams, including history in the field of developmental disabilities; the definition of a team; models of teamwork; factors that contribute to or present a challenge to interdisciplinary team collaboration; conceptual models used to evaluate interdisciplinary teams; and a review of the research on interdisciplinary teams. In referring to “disciplines,” we imply that the family is a discipline that has a specific body of knowledge to contribute as a member of the interdisciplinary team. Also, the term health care in the context of the interdisciplinary team approach does not mean solely medical care focusing on biological factors; it also includes behavioral factors, as well as physical and social environmental factors.1

HISTORY

Isolated models of interdisciplinary health care teams, as defined as professionals from two or more disciplines working together, have existed in the United States since the beginning of the 20th century. Complex social issues related to the effects of industrialization (e.g., poverty, overcrowded housing, child labor) began to come to attention in the early 1900s, and there was a recognition among some professionals that health care involved joining “medical care with social fact.”2 The first publication in the United States to introduce the concept of interdisciplinary care is attributed to Richard Cabot of Massachusetts General Hospital; in 1915, he wrote about the value of… teamwork of the doctor, educator and social worker in the clinical efficiency.”3

With World War I, and to a greater extent with World War II, rehabilitation teams emerged to address the needs of veterans. After World War II, there was a rapid expansion of knowledge in medicine, an increase in accompanying technology, and the emergence of new specialties.4 Simultaneously in the 1940s, a new body of knowledge known as group dynamics was emerging from the fields of social psychology, sociology, and anthropology.5 In the mid-1940s, knowledge from the fields of group dynamics, social psychology, and educational psychology were melded to develop the unstructured Training Group (T-Group) as an intensive learning experience in small-group behavior.6

In the early1960s, issues related to poverty became a major national focus, and the concept of “comprehensive care” provided by interdisciplinary teams evolved as a means of addressing both social and medical needs of the individual.4 Demonstration team-managed neighborhood health centers were established in underserved areas to provide comprehensive care, which included medical, social, and vocational services. These types of clinics rapidly expanded during the 1970s to more than 850 by 1980.7 At the same time, knowledge in the field of group dynamics/theory was expanding to such areas as the integration of personal learning and planned action for social improvement, phases of group development, communication in groups, and conditions that encourage group participation.5

In the equal rights climate of the 1960s, there emerged a professional interdisciplinary movement that embraced the team concept as an approach to improve health care delivery. The team concept was also viewed by some professionals as a means of achieving a greater equality in status of certain disciplines, which in turn would lead to improved health care delivery.4,8 For example, in 1971, Madeleine Leininger9 stated the following in an article about interdisciplinary education:… in our future conceptualizations of health education and service models, there is a need to consider ways to reduce and redistribute physician power so that other health disciplines and consumers can share in his power, decision-making, and the control of health matters and resources” (p 789).

The 1970s marked the integration of group theory principles into examining interdisciplinary health care teams.9–12 Also, aging of the population became of concern, and interdisciplinary teams began to increase within the field of geriatrics. During this period, the Department of Veterans Affairs implemented the Interdisciplinary Team Training in Geriatrics program, a clinically based educational program for both staff and students. The program eventually expanded beyond geriatrics and became the Interprofessional Team Training and Development Program.13 In the 1980s, the Bureau of Health Professions also began awarding Geriatric Education Center and Rural Health initiative grants to universities to teach collaborative teamwork practices to professionals in medical and health-related fields for working in the area of geriatrics and to students working in rural areas.

The 1990s were a time of changes in the health care environment, with increased reliance on primary care, disease prevention, evidence-based practice, and cost containment. Health care organizations incorporated organizational and management theory into their operations and adopted concepts of total quality management, total quality improvement, and continuous quality improvement.14 “Team” became a buzz word, and self-directed work groups emerged to address issues related to reducing costs and increasing productivity. In 1995, the Pew Health Professions Commission issued Critical Challenges: Revitalizing the Health Professions for the Twenty-First Century.15 This report presented a comprehensive analysis of the trends and strategies for successful outcomes in health care. One of the Commission’s recommendations for the future was team training and cross-professional education for all health professionals. In relation to this recommendation, the Commission expressed concern that model experiments involving team training and cross-professional education had stopped; the Commission urged that they be “rekindled” through “more sharing of clinical resources, more cross-teaching by professional faculties, more exploration of the various roles played by professionals and the active modeling of effective team integration in the delivery of efficient, high quality care” (p 22).

The beginning of the 21st century is an era in which teamwork is becoming a norm within health care organizations. With the Institute of Medicine’s 1999 report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System,16 teamwork became to be viewed as crucial for ensuring patient safety, and a variety of medical team training programs began to emerge.17 After publication of the report, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality commissioned an evidence-based literature review regarding safety improvement, which included a review of Crew Resource Management (CRM) and its application to medicine.18 CRM, an approach to safety training focusing on effective team management, was developed by experts in aviation to improve the operation of flight crews and was beginning to be applied to high-stress decision-making health care environments such as the operating room, the labor and delivery suite, and the emergency room. Although additional evidence-base studies were indicated, it was concluded that CRM had tremendous potential applications in the health care field.18 By 2005, a variety of CRM-based medical training programs had been developed with the goal of reducing the number of medical errors through the application of teamwork skills training. A formal review of six of these medical training programs was commissioned by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of a report on what federally funded programs had accomplished in understanding medical errors and implementing programs to improve patient safety over the 5 years since To Err is Human was published.17 Among the recommendations that resulted from the review was the recommendation that “the health care community develop a standard set of generic teamwork-related knowledge, skill and attitude competencies” (p 263).

As the team concept was gaining momentum in the actual delivery of health care, it was also gaining momentum in relation to the educational preparation of health care professionals. The 2001 Institute of Medicine report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century19 expressed concern that although health professionals were asked to work in interdisciplinary teams, they did not receive education together or receive training to develop team skills. A recommendation of Crossing the Quality Chasm was that a multidisciplinary summit of leaders within the health professions be held to identify strategies for restructuring educational programs. The summit was convened in 2002, and recommendations were issued in the 2003 report Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality.20 Resulting was an overarching vision for clinical education in the health professions: “All health professions should be educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interdisciplinary team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement approaches, and informatics”(p 3). To achieve this vision, five core competencies for the areas identified were proposed as competencies that all clinical health professions should possess. The challenge ahead will be for the traditionally autonomous health professions to agree that these core competencies should indeed become part of the curricula for all clinical health professions.

HISTORY WITH REGARD TO CHILDREN WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

The Children’s Bureau, established in 1912, was the first government agency to focus on providing services to all children, including children with mental retardation and disabilities. In 1954, the Children’s Bureau awarded a project grant to the Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles to establish an interdisciplinary diagnostic clinic for children with mental retardation. By 1956, the Children’s Bureau had 36 demonstration projects to provide services to children with mental retardation, develop new methods of service delivery, and provide training for professional workers.21

With the 1960s, there emerged an emphasis on focusing not only on the treatment of a specific disability but also on the child who happened to have the disability and on his or her family.22 Inspired by personal experience, President John F. Kennedy created a President’s Panel on Mental Retardation in 1961 to advise him on how the federal government could best meet the needs of children with mental retardation and of their families. In 1962, the Panel issued a report that included recommendations for more comprehensive and improved clinical services, as well as efforts to overcome serious problems of personnel in the field.23 Legislation signed into law by President Kennedy in 1963 and funding provided by Amendments to Title V of the Social Security Act is administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration of the Public Health Service Department of Health and Human Service and legislates maternal and child health programs. In 1965 led to the development of University Affiliated Facilities (UAFs) in medical centers to provide both comprehensive interdisciplinary services to children with mental retardation and interdisciplinary training in the evaluation and management of children with mental retardation. This was considered a major breakthrough to systematically address personnel needs for children with mental retardation. It was the first time that the Congress and the Executive Branch recognized the need for federal funds to assist in establishing a national network of interdisciplinary training programs centered on models of service.24 However during this period, the interdisciplinary team approach to service and training did not go without criticism on a variety of grounds. Many of the critics believed that the expense of the interdisciplinary approach was not warranted; that there was an excessive duplication in the evaluation; and poor team dynamics resulted from conflicts among disciplines, personal frictions, defense of territory, or domination by one discipline or team member.25

Legislation in 1972 expanded the service and training roles of UAFs to include both children with mental retardation and those with other developmental disabilities. The number of UAFs continued to grow, and by the mid-1970s, there were about 40 in 30 states. In 1976, a UAF Long Range Planning Task Force was established to reassess the original UAF concept and make recommendations as to their future direction and role. Their reassessment indicated that, overall, the original UAF concept was sound and experience had proved that the program concept was effective in meeting a significant social need.24 On the basis of the review, the Task Force made a number of recommendations to modernize and extend the program to serve individuals, both children and adults, with developmental disabilities in all states. The Task Force also reaffirmed the importance of training, both pre-service and in-service, as a role of the UAFs and endorsed a definition of interdisciplinary training, which had been developed by UAF training directors:

The reader is referred to the UAF Long Range Planning Task Force report The Role of Higher Education in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities.24 The values and concepts related to interdisciplinary training and service described are as important today as they were in 1976.

The funding for the programs came from two sources the Administration for Developmental Disabilities and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The Maternal and Child Health Bureau programs maintained a stronger child and health focus than did those funded by the Administration for Developmental Disabilities. These programs became the Leadership Education in NeuroDevelopment and Related Disabilities (LEND). The LEND programs were developed by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau to improve the health status of infants, children, and adolescents with or at risk for neurodevelopmental and related disabilities and the health status of their families. This is accomplished through the training of professionals for leadership roles in the provision of health and related care, continuing education, technical assistance, research, and consultation.

WHAT IS A TEAM?

There are multiple definitions of what a team is; many of the definitions are based on different theoretical frames of reference. One definition, based on organizational design theory, that is frequently cited is that a “team” is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.26 The four elements of this definition are as follows:

Although the term team is often used interchangeably with workgroup, it is viewed as different in several ways. Katzenbach and Smith31 identified both collective performance and mutual responsibility as two major ways in which teams differ from workgroups. In their view, a workgroup’s performance is a function of what its members do as individuals, and responsibility for performance is solely at the individual level. Drinka40 distinguished between the two on the basis of three factors present in health care teams, but not workgroups, that can negatively affect group process: presence of autonomous disciplines who are used to doing things independently of other disciplines; the ongoing nature of health care teams rather than being time-limited, as workgroups are; and the continual entering and leaving of members as a result of high staff turnover.

MODELS OF TEAMWORK

The composition, organization, and functioning of health care teams varies widely among institutions, medical specialties, and type of services offered.41 Many teams include a number of loosely associated personnel or a smaller number of highly interdependent professionals. Multiple terms are used in an attempt to describe the different models of current health care teams, including unidisciplinary, intradisciplinary, cross-disciplinary, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, intraprofessional, and transdisciplinary. The most common terms, often used interchangeably, are multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisicplinary. All three models are based on the recognition that no one discipline has the breadth of knowledge and skills that are necessary to provide quality health care.

Unidisciplinary

This term in the past has not been included as a model of teamwork, because it was traditionally used to refer to one professional working independently in his or her specialty. Historically, in terms of the interdisciplinary approach, it also implied a professional who perceived himself or herself as have the knowledge and skills needed to identify and address all areas related to his or her field of focus. The well-known fable of “The Blind Men and the Elephant” has often been used as a metaphor in describing unidisciplinary functioning. Just as each man who was blind determined what the elephant was like on the basis of the individual part the man touched, each discipline perceives the individual in a unique, valid way and yet risks remaining “blind” to the total individual. With the emergence of single-discipline group practices, the term is also used at times to refer to two of more professionals in a discipline who share the same professional skills and training, have a common language, and function in a group.42 As a result of increased specialization within medicine, unidisciplinary, or what sometimes is referred to as intradisciplinary, has been used to describe a team of professionals in a discipline who have additional professional skills and training in varying specialty areas and, although they share some common language, have developed a language specific to their specialty. An example of a unidisciplinary team would be a pediatric urologist, a pediatric neurologist, and a pediatric orthopedist who communicate with each other and share information in the provision of care to an individual child.

Multidisciplinary

Some authorities also equate the multidisciplinary team model with “The Blind Men and the Elephant” in that each discipline “feels” or focuses on its own area. The difference with the multidisciplinary team is that there is some form of communication about the information that was obtained that potentially contributes to decision making with regard to the “whole.” There is, as a result, less chance for one person’s mistakes or biases to determine the course of events.43 However, the model can result in simply piecing information together on the basis of the individual discipline results, especially if the model is implemented without the opportunity for interaction between team members at a team meeting.38

Interdisciplinary

One of the strengths of the interdisciplinary model is the integration of the individual contributions of team members to address a common set of issues or problems.37,45–47 Another strength is the collaborative decision making that occurs to establish a holistic plan of care or recommendations.37,45,47 Over time, the team members also develop a “common language” that facilitates communication and collaborative decision making.36,37 The interdisciplinary team model, however, also presents several challenges, which are discussed separately.

Transdisciplinary

The features most frequently identified in relationship to transdisciplinary teams are as follows:

Strengths of the transdisciplinary model include a high degree of interaction and coordination; increased agreement among team members about the acceptability of recommendations; enhanced opportunities for team members to learn from one another; decreased fragmentation of services; and increased continuity and consistency of services.43 Also, in the area of early intervention, limiting the number of people who come in contact with a very young child prevents duplication of services and unnecessary intrusion into family activities and routines.44 Although the high degree of interaction and coordination is a strength, it is also a potential challenge in that the required degree of role sharing and transfer may lead to role ambiguity, role conflict, and role release to the extent of loss of professional identity.43

Transdisciplinary has also been used to refer to teams of multiskilled health practitioners who are trained to provide a wide range of services in a specific field, such as geriatrics, apart from training in a traditional discipline.38 This approach to the provision of health care has also been referred to as a pandisciplinary model, in which a single new discipline’s role spans all areas of competence relevant to a specific field.42 Unfortunately, in many ways, the pandisciplinary model brings teamwork full circle back to an unidisciplinary approach in which practitioners from one discipline assume that they have all the knowledge and skills needed to provide services in a particular field.

Each model of teamwork described has its strengths and challenges. Some professionals advocate one model over, implying that the particular model is better than others. It is more constructive to think of the models as points along a continuum of approaches, all of which have the common goal of providing high-quality services to children with developmental disabilities and to their families. Different programs serving children with developmental disabilities and their families use different models along this continuum to reach the common goal. For a program that provides ongoing services to a large number of children with medically complex health needs that necessitate the involvement of multiple medical specialties, the multidisciplinary team model may be the only feasible model. However, in a program that provides diagnostic and treatment services for children of varying ages with a broad range of developmental disabilities, the interdisciplinary team approach may be the model by which services are provided for older children, and the transdiciplinary model, by which services are provided for very young children and their families.

In the interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary model, and frequently in the multidisciplinary model, decision making involves face-to-face interaction. A new type of team, the virtual team, is emerging in the health care field. Virtual teams have been used in business for some time and consist of geographically or organizationally dispersed members who use technologies to perform team tasks.48 Rather than communication during face-to-face meetings, communication and decision making are accomplished through such technologies as email or video teleconferencing. Within health care, with the increasing demands for productivity and changing reimbursement, traditional models of teamwork may no longer be as functional as they once were and may be replaced by virtual teams.49,50 According to a developing body of knowledge about virtual teams, virtual teams apparently go through the same stages of team development and confront the same interpersonal process issues that exist in teams that meet face to face.51,52

FACTORS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO INTERDISCIPLINARY TEAM COLLABORATION

As discussed under the definition of a team, three important factors are complementary skills (discipline skills, problem-solving and decision-making skills, and interpersonal skills), commitment to a common purpose, and mutual accountability. Closely related to these factors are the concepts of shared leadership roles and shared power.31,33,37,39 Shared leadership means that each team member, depending on the situation, assumes the role of either team leader or team member.53 Historically, interdisciplinary teams tended to have one member who was designated the team leader upon whom the onus was placed for the success or failure of the team. A large body of literature emerged addressing leadership roles and styles of successful and unsuccessful team leaders. Slowly the responsibility for success or failure of interdisciplinary teams in achieving their goals shifted also to team members, and literature focusing on the attributes and behaviors of effective team members began to emerge.38 As the concept of shared leadership evolved, the concept of shared power among team members, regardless of educational or professional preparation, also evolved.39 Power and status within the interdisciplinary team was historically accorded to the physician, who usually was also the team leader.9,37,54 However, other hierarchies also exist not only between other disciplines but also within disciplines, on the basis of educational preparation (e.g., doctoral, master’s, bachelor’s degrees).37,55 Shared power is viewed as a means to bestow each team member equal status within the interdisciplinary team. This concept is especially important if family members are truly to be members of the interdisciplinary team.

Among the additional factors that have been identified as contributing to interdisciplinary team collaboration are individual or personal attributes. Simply placing someone in a team will not make him or her an effective team member. The reality is that some people are egocentric and do not have the collective orientation to be team members.56 Some of the individual attributes identified as enhancing interdisciplinary team function are flexibility and adaptability31,34 and the abilities to view diverse perspectives as learning opportunities, to engage in critical thinking, and to synthesize information adaptability.57

Another factor that is frequently mentioned as contributing to interdisciplinary team collaboration is the development of “common language” among the team members. Individual disciplines speak different languages that contain very discipline-specific terminology, jargon, and acronyms,37 which become even more difficult to understand the more specialized a discipline becomes.58 The process of developing a common language takes time and evolves from communication and learning that occurs as the team works together. It involves recognizing that, for disciplinary knowledge explicit and accessible to other disciplines, it must be translated into a language that other people will understand.36 However, members of other disciplines must be comfortable enough within the team to ask for clarification when they do not understand members of another discipline. Another problem of “common language” that often takes a longer time to surface occurs when two or more disciplines use a common term and thus think they are communicating, when in reality they are not because they define the term differently in subtle ways.

Just as members of different disciplines speak different languages, they differ in other ways. It has been suggested that viewing disciplines as culturally diverse groups will result in a better understanding of and respect for the diverse perspectives of the disciplines.57,59 Some of the ways in which disciplines, like cultures, may differ are in their theoretical orientation and assumptions (e.g., biomedical, behavioral, and biopsychosocial)37,60; their mode of thinking (e.g., divergent/inductive vs. convergent/deductive)55,61; and values (e.g., saving life vs. quality of life).60,61 Also involved is developing an understanding of such areas as the education, levels of practice, areas of expertise, and roles of the individual disciplines.37,42,62 By learning about one another, team members not only develop a better general understanding of one another but are able to identify the specific roles and responsibilities of individual team members, how they interface with each other, and where their disciplines overlap.42,60

FACTORS THAT PRESENT CHALLENGES FOR INTERDISCIPLINARY TEAM COLLABORATION

The organizational structures in which interdisciplinary teams operate are vital to their survival and significantly affect their performance.39,63–65 In an era in which teamwork is becoming a norm within health care organizations, there is concern that many health care organizations may not be ready or able to support interdisciplinary teams as the norm in service provision.35,66 The interdisciplinary approach requires an organizational structure that values the interdisciplinary team approach and is able to support the approach fiscally. Increased emphases on fee-generating services and productivity are already having affecting the provision of interdisciplinary team services in organizations in which this approach to service provision has been used, especially in which health care team services cannot also be covered by facility charges.67 The fee-for-service structure and current reimbursement policies are real barriers to the interdisciplinary team approach68 and are being questioned if the team model, although based on “best practices,” is financially viable.67 Settings in which the interdisciplinary approach is used to serve children with developmental disabilities and their families are facing the same emphases on fee-generating services and productivity as are other settings that provide services through the interdisciplinary approach. The issue of reimbursement for services has created the hierarchy of disciplines that can generate fees and disciplines that cannot; those that cannot are at risk of no longer being included in the provision of services to the degree they once were. Also, one of the advantages of the interdisciplinary team approach has been the team meetings, which provide team members the opportunity to learn from one another, share information, and participate in collaborative decision making and planning. Current payment policies, however, do not cover the time involved in team meetings.68 As a result, some settings that had been based on an interdisciplinary team model of services have had to retrench to the multidisciplinary model.

A second challenge to the interdisciplinary team collaboration is the current status of interdisciplinary education. Although interdisciplinary training has been promoted in areas such as developmental disabilities, geriatrics, rehabilitation, and primary care for underserved populations since the 1960s, it has never been widely incorporated into disciplinary training. Disciplinary education is viewed as a means of socializing a student to his or her future roles within the discipline. This role socialization has often been considered a major barrier to interdisciplinary teamwork because it is conducted in isolation from other disciplines.9,35,42,54,58,63 Not only is it conducted in isolation but also students are not necessarily rewarded for looking beyond their discipline for knowledge. Frequently, students are awarded grades on written assignments on the basis of their knowledge of disciplinary literature rather than their ability to integrate congruent or noncongruent knowledge from other disciplines into their assignment.

Ducanis and Golin63 identified three elements of interdisciplinary or team training: cognitive information, affective and experiential learning, and clinical competence. Within universities, there have been isolated models of interdisciplinary training that have especially addressed the areas of cognitive information and experiential learning, but for the most part they have not been widely incorporated.15,19 As with the implementation of the interdisciplinary team approach within health care organizations, interdisciplinary education requires a university structure that values the interdisciplinary education and is willing to support the approach fiscally.42,54 In addition, universities have been challenged with integrating additional emerging discipline-specific knowledge areas into already crowded curricula; when faced with this situation, faculty members are more likely to support discipline-specific knowledge than interdisciplinary knowledge.54

CONCEPTUAL MODELS USED TO EVALUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY TEAMS

Multiple conceptual models have been used to study and evaluate interdisciplinary teams. In some models, originating from group process theory, teams are viewed as evolving through various developmental stages. One of these models was developed by Drinka40 and identifies the stages as forming, “norming,” confronting, performing and leaving. Another model, developed by Lowe and Herranen,69 identifies the stages as becoming acquainted, trial and error, collective indecision, crisis, resolution, and team maintenance. One of the differences in the models is that the first model recognizes that team membership does not remain constant and, as team members leave and new team members enter, there is an effect on team performance. In additional models, teams are viewed in terms of group problem solving as an indicator of group effectiveness,62,70 the social climate of the groups,71 group interactions and relational norms,65 or role behavior and conflict.54

As organizational theory began to be applied to interdisciplinary teams, models were developed in which teams were also viewed in terms of processes in different areas. In one model, teams are viewed in terms of the areas of establishing trust, developing common beliefs and attitudes, empowering team members, having effectively managed team meetings, and providing feedback about team functioning.33 Other models integrate multiple theoretical perspectives into the model. For example, a model developed by Bronstein34 focuses on team processes in the areas of interdependence, newly created professional activities, flexibility, collective ownership of goals, and reflection on process. All these models focus on team process as indicators of team performance, with the assumption that an effectively functioning interdisciplinary team will provide quality services. However, it has been suggested that process measures really do not reflect team outcome and are important primarily for team training purposes when the intent is to identify performance issues and provide feedback to assist the individual in improving his or her behavior.35

REVIEW OF THE RESEARCH ON INTERDISCIPLINARY TEAMS

Several articles have included extensive reviews of the literature regarding interdisciplinary team care. The majority of these reviews concluded that there is little evidence of the effectiveness of interdisciplinary teams.45,53,60,68,72,73 These reviews of the literature also indicated the following:

Interestingly, the implementation of the interdisciplinary team approach on the basis of assumption is not unique in relation to the team approach. An example is the CRM approach to teamwork skills training, which serves as the basis for a variety of medical training programs focusing on reducing medical errors. The CRM has been used since 1980 to improve the operation of flight crews, despite the lack of definitive evidence that CRM decreases aviation errors.18 In addition, despite years of research regarding team performance in the military and corporate world, very little is known about the factors of that determine effective team performance.56

Schofield and Amodeo73 conducted an extensive review of the literature related to interdisciplinary teams in health care and human services settings. Not only did they conclude that there is limited evidence regarding the effectiveness of interdisciplinary teams, but the review also provided information regarding the fields from which the articles originated and the types of articles that have been written about interdisciplinary teams. From abstracts, Schofield and Amodeo identified 224 articles that potentially focused on the interdisciplinary approach to the provision of services. The majority of articles were in the fields of rehabilitation, geriatrics, health services, and mental health services; fewer than 25 articles were found in the field of developmental disabilities. After they eliminated articles that used the terms multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary without additional explanation, there were 138 potentially useful articles. Of theses articles:

Although concluding that there is little evidence regarding the effectiveness of interdisciplinary teams, the authors of these literature reviews acknowledged that research regarding interdisciplinary teams is complex and presents several challenges.68,72,74 For one thing, no two teams appear to be alike. The structure of interdisciplinary teams varies greatly between settings and, at times, within settings in terms of structure (e.g., composition of disciplines and number of team members).68 In addition, interdisciplinary teams function in clinical settings in which it is more difficult to use rigorous research designs.72 Third, the concept of the interdisciplinary team is to use the knowledge and skills of a number of disciplines to address a range of needs rather than an outcome in one area. As a result, the outcome of interdisciplinary team care becomes multidimensional and is more difficult to measure.72

Today there is an emphasis on cost containment, productivity, and evidence-based practice. If the interdisciplinary team approach is to survive this era, the approach based on assumption can no longer be justified. Research regarding the effectiveness of the interdisciplinary team approach needs to be better conceptualized, employ more sophisticated research designs when possible, and focus on both process and outcome.35,73 Studies must also clearly define what is meant when the terms multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary are used73 and must capture individual and team-level performance.35 Some of the specific challenging questions for future research include the following:68

1 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 20010, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2000.

2 Brown TM. An historical view of health care teams. In: Agich GJ, editor. Responsibility in Health Care. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel; 1982:3-21.

3 Cabot R. Social Service and the Art of Healing. New York: Moffat, Yard & Company, 1915.

4 Keith RA. The comprehensive treatment in rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:269-274.

5 Royer JA. Historical overview: Group dynamics and health care teams. In: Baldwin DC, Rowley BD, editors. Interdisciplinary Health Team Training. Lexington: University of Kentucky, Center for Interdisciplinary Education in Allied Health; 1982:12-28.

6 Benne KD, Bradford L, Gibb J, et al. The Laboratory Method of Changing and Learning. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books, 1975.

7 Lefkowitz B. The health center story: Forty years of commitment. J Ambul Care Manage. 2005;28:295-303.

8 Purtilo RG. Interdisciplinary health care teams and health care reform. J Law Med Ethics. 1994;22:121-126.

9 Leininger M. This I believe … about interdisciplinary education for the future. Nurs Outlook. 1971;19:787-791.

10 Wise H, Beckard R, Rubin I, et al. Making Health Teams Work. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger, 1973.

11 Wise H, Rubin I, Beckard R. Making health teams work. Am J Dis Child. 1974;127:537-542.

12 Kane RA. The interprofessional team as a small group. Soc Work Health Care. 1975;1(1):19-31.

13 Reuben DB, Levy-Storms L, Yee MN, et al. Disciplinary split: A treat to geriatrics interdisciplinary team training. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1000-1006.

14 Drinka TJK. Applying learning from self-directed work teams in business to curriculum development for interdisciplinary geriatric teams. Educ Geront. 1996;22:433-450.

15 Pew Health Professions Commission. Critical Challenges: Revitalizing the Health Professions for the Twenty-First Century. Berkeley, CA: University of California at Berkeley, Center for Health Professions, 1995.

16 Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2000.

17 Baker DP, Gustafson S, Beaubien JM, et al. Medical team training programs in health care. In: Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation. Volume 4: Programs, Tools, and Products (AHRQ Publication No. 050021 [4]). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005:253-267. pp. (Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/advances; accessed 10/23/06.)

18 Pizzi L, Goldfarb NI, Nash DB. Crew resource management and its application in medicine. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 43(AHRQ Publication No. 01-E058). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001:501-509. (Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety; accessed 10/23/06, Chapter 44.)

19 Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2001.

20 Institute of Medicine. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003.

21 Peppe KK, Sherman RG. Nursing in mental retardation: Historical perspective. In: Curry JB, Peppe KK, editors. Mental Retardation: Nursing Approaches to Care. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1978:3-18.

22 Sheridan MD. The Handicapped Child and His Home. London: National Children’s Home, 1965.

23 The President’s Panel on Mental Retardation: A Proposed Program for National Action to Combat Mental Retardation. Washington, DC: Superintendent of Documents, 1962.

24 UAF Long Range Planning Task Force. The Role of Higher Education in Mental Retardation and Other Developmental Disabilities. Washington, DC: Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1976.

25 Chamberlin HR. The interdisciplinary team: Contributions by allied medical and nonmedical disciplines. In: Gabel S, Erickson MT, editors. Child Development and Developmental Disabilities. Boston: Little, Brown; 1980:435-470.

26 Katzenbach JR, Smith DK. The Wisdom of Teams. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1993.

27 Cowell J, Michaelson J. Flawless teams. Executive Excellence. 2000;17(3):11.

28 Hrickiewicz M. What makes teams successful? Health Facil Manage. 2001;14(3):4.

29 Stahelski AJ, Tsukuda RA. Predictors of cooperation in health care teams. Small Group Res. 1990;21:220-233.

30 Poulton BC, West MA. The determinants of effectiveness in primary health care teams. J Interprof Care. 1999;13:7-18.

31 Katzenbach JR, Smith DK. The discipline of teams. Harv Bus Rev. 1993;71(2):111-120.

32 Sands RG, Stafford RG, McClelland M. “I beg to differ”: Conflict in the interdisciplinary team. Soc Work Health Care. 1990;14(3):55-72.

33 Dukewits P, Gowan L. Creating successful collaborative teams. J Staff Dev. 1996;17(4):12-16.

34 Bronstein LR. A model for interdisciplinary collaboration. Soc Work. 2003;48(3):113-116.

35 Baker DP, Salas E, King H, et al. The role of teamwork in the professional education of physicians: Current status and assessment recommendations. J Qual Patient Safety. 2005;31:185-202.

36 De Wachter M. Interdisciplinary teamwork. J Med Ethics. 1976;2:52-57.

37 Pearson PH. The interdisciplinary team process, or the professionals’ Tower of Babel. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1983;25:390-397.

38 Frattali CM. Professional Collaboration: A Team Approach to Health Care. Clinical Series No. 11. Rockville, MD: National Student Speech Language Hearing Association, 1993.

39 Orchard CA, Curran V, Kabene S. Creating a culture for interdisciplinary collaborative professional practice. Med Educ Online. 2005;10:11. (Available at: http://www.med-ed-online.org; accessed 10/24/06.)

40 Drinka TJ. Interdisciplinary geriatric teams: Approaches to conflict as indicators of potential to model teamwork. Educ Gerontol. 1994;20:87-103.

41 Ellingston LL. Communication, collaboration, and teamwork among health care professionals. Commun Res Trends. 2002;21(3):3-21.

42 Satin DG. A conceptual framework for working relationships among disciplines and the place of interdisciplinary education and practice: Clarifying muddy waters. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 1994;14(3):3-24.

43 McCollum JA, Hughes M. Staffing patterns and team models in infancy programs. In: Jordan JB, editor. Early Childhood Education: Birth to Three. Reston, VA: Council for Exceptional Children; 1988:130-146.

44 Briggs MH. Team decision-making for early intervention. Infant Toddler Interv Transdiscip J. 1991;1(1):1-9.

45 Wiecha J, Pollard T. The interdisciplinary eHealth team: Chronic care for the future. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e22. (Available at: http://www.jmir.org/2004/e22/; accessed 10/24/06.)

46 Meeth LR. Interdisciplinary studies: A matter of definition. CHANGE. 1978;10(7):10.

47 Hall P, Weaver L. Interdisciplinary education and teamwork: A long and winding road. Med Educ. 2001;35:867-875.

48 Maruping LM, Agarwal R. Managing team interpersonal process through technology: A task-technology fit perspective. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89:975-990.

49 Cole KD. Organizational structure, team process, and future directions of interprofessional health care teams. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2003;24(2):35-49.

50 Rothschild SK, Lapidos S. Virtual integrated practice: Integrating teams and technology to manage chronic disease in primary care. J Med Syst. 2003;27(1):85-93.

51 Vroman K, Kovacich J. Computer-mediated interdisciplinary teams: Theory and reality. J Interprof Care. 2002;16:159-170.

52 Furst S, Reeves M, Rosen B, et al. Managing the life of virtual teams. Acad Manage Exec. 2004;18(2):6-20.

53 McCallin A. Interdisciplinary team leadership: A revisionist approach for an old problem? J Nurs Manage. 2003;11:364-370.

54 Aaronson WE. Interdisciplinary health team role taking as a function of health professional education. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 1991;12(1):97-110.

55 Drinka TJK. From double jeopardy to double indemnity: Subtleties of teaching interdisciplinary geriatrics. Educ Gerontol. 2002;28:433-449.

56 Driskell JE. Collective behavior and team performance. Hum Factors. 1992;34:277-288.

57 Vincenti VB. Family and consumer sciences university faculty perceptions of interdisciplinary work. Fam Consum Sci Res J. 2005;34(1):81-104.

58 Garner HG. Challenges and opportunities of teamwork. In: Orelove FP, Garner HG, editors. Teamwork: Parents and Professionals Speak for Themselves. Washington, DC: Child Welfare League of America; 1998:11-29.

59 Clark P. Values in health care professional socialization: Implications for geriatric education in interdisciplinary teamwork. Gerontologist. 1997;37:441-451.

60 Simpson G, Rabin D, Schmitt M, et al. Interprofessional health care practice: Recommendations of the National Academies of Practice expert panel on health care in the 21st century. Issues Interdiscip Care: Natl Acad Pract Forum. 2001;3(1):5-19.

61 Qualls SH, Czirr R. Geriatric health teams: Classifying models of professional and team functioning. Gerontologist. 1988;28:372-376.

62 Christensen C, Larson JR. Collaborative medical decision making. Med Decis Mak. 1993;13(4):339-346.

63 Ducanis AJ, Golin AK. The Interdisciplinary Health Care Team: A Handbook. Germantown, MD: Aspen, 1979.

64 Butterill D, O’Hanlon J, Book H. When the system is the problem, don’t blame the patient: Problems inherent in the interdisciplinary inpatient team. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37:168-172.

65 Amundson SJ. The impact of relational norms on the effectiveness of health and service teams. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2005;24:216-224.

66 Cashman SB, Reidy P, Cody K, et al. Developing and measuring progress toward collaborative, integrated, interdisciplinary health care teams. J Interprof Care. 2004;18:183-196.

67 Melzer SM, Richards GE, Covington MW. Reimbursement and costs of pediatric ambulatory diabetes care by using the resource-based relative value scale: Is multidisciplinary care financially viable? Pediatr Diabetes. 2004;5:133-142.

68 Cooper BS, Fishman E. The Interdisciplinary Team in the Management of Chronic Conditions: Has Its Time Come? Baltimore: John Hopkins University, Partners for Solutions, 2003.

69 Lowe JI, Herranen M. Understanding teamwork: Another look at the concepts. Soc Work Health Care. 1981;7(2):1-11.

70 Whorley LW. Evaluating health care team performance: Assessment of joint problem-solving action. Health Care Superv. 1996;14(4):71-76.

71 Brock D, Barker C. Group environment and group interaction in psychiatric assessment meetings. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1990;36:111-120.

72 Schmitt MH, Farrell MP, Heinemann GD. Conceptual and methodological problems in studying the effects of interdisciplinary geriatric teams. Gerontologist. 1988;28:753-764.

73 Schofield RF, Amodeo M. Interdisciplinary teams in health care and human service settings: Are they effective? Health Soc Work. 1999;24:210-219.

74 Opie A. Thinking teams thinking clients: Issues of discourse and representation in the work of health care teams. Sociol Health Illness. 1997;19:259-280.

8B. Family-Centered Care and the Medical Home

Societal changes have affected the relationship between families, children, and pediatricians.1,2 Technological advances, the growing prevalence of chronic disease in children, increasing empowerment of patients as consumers, and public access to information once available only through professionals, as well as the decreasing frequency of longitudinal patient-physician relationships, have affected the capability of the existing health care system to meet the needs of children and their families. If primary authority for clinical decision making in behalf of children is delegated to the pediatrician on the basis of professional expertise, there is a risk of minimizing the family’s lived experience; therefore, from many perspectives, traditional roles are no longer preferred. Instead, many families and pediatricians desire a relationship in which the contributions of each is valued. These role changes, along with acknowledgement that the health care system is failing to produce desired outcomes despite dramatically spiraling costs, urge redesign.3 Efforts to improve the quality of health care have focused on transforming biomedically dominated care processes to those guided by patients’ and families’ unique needs and values. In this chapter, we address relationship-focused quality improvement strategies by exploring the concept of family-centered care, examining selected evidence linking family-centered care to outcomes for children and families, discussing how family-centered care is applied in the medical home model within pediatric primary health care settings, and suggesting future directions in family-centered care practices and research.

HISTORICAL FOUNDATIONS OF THE FAMILY-CENTERED CARE CONCEPT

Family-centered care is one of several terms referring to a patient-centric view of the patient-physician relationship, and this concept is a relatively recent social movement. Although the concept began gaining momentum largely through the advocacy led by parents of children with special health care needs (CSHCN) in the 1980s, aspects of its underlying principles can be found in philosophical writings on the patient-physician relationship from ancient through contemporary times.3–5 Through the years, the concept has been discussed under the guise of different labels, including client-centered therapy,6 patient-centered care,4,7 and relationship-centered care.8 The common theme is that successful caregiving requires not only accurately diagnosing disease but also valuing the importance of human interactions in health care experiences and the legitimacy of the patient’s beliefs and preferences. Patient centeredness is frequently described by contrasting it to physician or system centeredness; the difficulty in attaining the required paradigm shift is highlighted by comparison to the inversion of thinking necessary to view the sun rather than the earth as the center of the universe.9 In a system-centered model, care processes are structured to facilitate the function of health care professionals to serve patients; patients must adapt to the constraints of the system. When a patient-centered model is used, the opposite is true: The system accommodates the individual. In pediatrics, patient-centered care is typically referred to as family-centered care to acknowledge that children’s well-being is inextricably linked to that of their families. A family-centered approach requires recognition that families have the most expertise about their child and, therefore, that they have the right and the responsibility to collaborate in medical decision making in behalf of their child.9,10 The following sections highlight some of the historical forces that have shaped the concept of family-centered care, including policy changes affecting family presence during hospitalizations, epidemiological changes in children’s health, broadening views of health determinants, and growing numbers of families raising CSHCN. Theoretical benefits of family-centered care, as well as empirical evidence regarding the efficacy of its use, are examined later in the chapter.

Changes in Hospital Policies Affecting Families Rights and Responsibilities

Even until the late 1950s, most medical professionals believed that visits from parents to their hospitalized children would inhibit effective care. Observations that children cried more in the presence of a parent or became distressed when their parent left led physicians and nurses to interpret parental visits as harmful for children.11 As a result, parents were regularly excluded from partnership in medical decision making about their children. By the 1970s, because of accumulating evidence that episodes of separation from their parents had the potential to harm children’s psychological well-being,12–14 U.S. hospital policies began allowing parents to stay with their children during admissions.15 Newborns began rooming in with their mothers instead of group nurseries, and fathers were permitted in the delivery room to support mothers during labor.16 The restrictive hospital policies before the 1970s that curtailed the family’s ability to comfort a hospitalized child (or other family member) provide an example of strategies that maintained institutional and staff control and exemplify system-centered models of health care delivery.

Epidemiological Changes in Children’s Health and Broadening Views of Health Determinants

In the 1970s, health services researchers brought attention to the growing prevalence of children’s psychosocial difficulties. Haggerty and colleagues called this growing challenge “the new morbidity” in their 1975 publication, Child Health and the Community,17 and conceptualized the interdependence of the family, the community, and children’s health. The authors asserted that for pediatricians to remain relevant to the well-being of children, pediatric training and practice would have to shift from focusing solely on the individual child to examining broader contextual aspects, including the family. The shift in thinking that Haggerty and colleagues’ work prompted, together with the rising tide of consumerism, undoubtedly fostered child health professionals to begin exploring the value of encouraging parents to be partners in medical decision making.

Further support for the importance of the family to children’s health came in 1977 in Engel’s classic article presenting the biopsychosocial medical model.18 His argument for a new paradigm of medical thinking that moved beyond a solely biomedical view to one that incorporated the inseparability of social and psychological influences on human health lent further support to Haggerty and colleagues’ argument that pediatricians needed to shift their focus beyond the child to the family context in order to foster children’s health.

Children with Special Health Care Needs and Their Families

Increasing recognition of the growing proportion of CSHCN and the ability of the U.S. health care system to successfully meet their needs spurred public organizers and government policy makers to improve the lives of these children and their families. In the U.S., key agencies that pioneered the CSHCN and family-centered care movement included the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB), the Association for the Care of Children’s Health (ACCH), Association of University Centers of Excellence in Disabilities, and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). As a division of the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. federal government’s Department of Health and Human Services, MCHB has long been charged with improving all children’s, women’s, and families’ health and is the designated organization that allocates funds from the federal Social Security Title V Act. ACCH, a now-defunct public organization originally formed in the 1960s, advocated along with MCHB for children’s health care system improvements. In the 1980s and 1990s, both organizations, along with the AAP and Association of University Centers of Excellence in Disabilities, were instrumental in broadening the conceptualization of children’s chronic disabling health conditions beyond one divided into specific disease categories to a more general category labeled children with special health care needs, defined as:

Those children who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health care-related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.19

Former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop’s 1987 Conference on Children with Special Health Care Needs disseminated the first widely acknowledged definition of family-centered care in the United States.20 This definition, formulated before the conference by parents, professionals, and policy makers active in the ACCH and MCHB, was published as a monograph, “Family-centered Care for Children with Special Health Care Needs,” that came to be commonly known as “Big Red” because of the red color of the cover.21 The ACCH made further refinements of the “Big Red” definition in 1994,9 which resulted in the key principles of family-centered care listed in Table 8B-1.22 Although the ACCH eventually disbanded, the Institute for Family-Centered Care, established in 1992, assumed the role that ACCH played and continues to disseminate information to promote the practice of family-centered care through annual conferences, information publications, guidelines for hospitals, and consultations to individual health organizations.23 MCHB also continues to include family-centered care into its improvement mandates for CSHCN:

From Shelton TL, Stepanek JS: The key elements of family-centered care. In Family-Centered Care for Children Needing Specialized Health and Developmental Services, 3rd ed. Bethesda, MD: Association for the Care of Children’s Health, 1994, p vii.

The overall national agenda is to provide and promote family-centered, community-based, coordinated care for CSHCN and to facilitate the development of community-based systems of services for such children and their families.24

The concept of family-centered care has undergone further refinements by researchers interested in early intervention services for CSHCN. Dunst and colleagues found that early intervention professionals and programs employing an empowering or enabling helpgiving relationship model more effectively achieve desirable child and family outcomes. The work of Dunst and colleagues has focused on outcomes, including family self-determination, decision-making capability, control, and self-efficacy and has precipitated a deeper understanding of the family-centered concept.25 They have extended the notion of family-centered care from one of simply incorporating parents in the delivery of health care to their children to the broader ideals of family-empowerment and marshalling community supports that are individualized by child and family need instead of imposing help from menu-driven service systems. Family empowerment has been explained as follows: “Family empowerment refers to families acquiring the capacity to exercise power. It makes them not just into actors, but into agents capable of shaping the conditions in which they live as they would want to shape them.”26 Dunst and colleagues proposed employing a conceptual framework of helpgiving relationships that empowers families by promoting family competency to identify and manage their child’s needs. Their model of empowerment requires specific conditions for both families and professionals. They require that families have (1) an increased understanding of their child’s needs, (2) the ability to deploy competencies to meet those needs, and (3) self-efficacy (a belief that they are capable) to do so.27 Among the conditions for help givers in their model are that professionals (1) have a proactive stance (help givers believe help seekers are already competent or have the capacity to become competent), (2) create opportunities for competence to be displayed (help givers provide enabling experiences to help seekers), and (3) allow help seekers to use their competencies to access resources and attribute success to their own actions, not the professional’s. In essence, Dunst and colleagues suggested that viewing the relationship from a strengths-based perspective rather than a deficit one is a more effective way to achieve desired outcomes for CSHCN and their families.

The multidisciplinary research group at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada also has done extensive work on refining the concept of family-centered care as it relates to CSHCN (note that they use the word service in place of the word care). In a summary of the theoretic and research literature,28 Rosenbaum attempted to organize the sometimes disparate meanings of family-centered service by dividing the concept into a three-level framework consisting of (1) basic premises or assumptions, (2) guiding principles, and (3) elements or key service provider behaviors. The basic premises are beliefs, values, and ideals about families and together form the backbone of the concept of family-centered service. Each premise has several guiding principles directed to professionals to help them ground their interactions with families. The elements are specific provider behaviors that follow from the assumptions and guiding principles. The addition of the key elements was an attempt to approach a definition that included measurable behaviors. Their conceptualization is summarized in Table 8B-2.

TABLE 8B-2 Premises, Principles, and Elements of Family-Centered Service

| Premises (Basic Assumptions) | ||

| Parents know their children best and want the best for their children. | Families are different and unique. | Optimal child functioning occurs within a supportive family and community context. The child is affected by the stress and coping family members. |

| Guiding Principles (“Should” Statements) | ||

| Each family member should have the opportunity to decide the level of involvement theywish in decision-making for their child. | Each family and family member should be treated with respect (as individuals). | The needs of all family members should be considered. |

| Parents should have the ultimate responsibility for the care of their children. | The involvement of all family members should be supported and encouraged. | |

| Elements (Key Service Provider Behaviors) | ||

| Service Provider Behaviors | Service Provider Behaviors | Service Provider Behaviors |

|---|---|---|

| To encourage parent decision-making | To respect families | To consider psychosocial needs of all members |

| To assist in identifying strengths | To support families | To encourage participation by all members |

| To provide information | To listen | To respect coping styles |

| To assist in identifying needs | To provide individualized service | To encourage use of community supports |

| To collaborate with parents | To accept diversity | To build on strengths |

| To provide accessible services | To believe and trust parents | |

| To share information about the child | To communicate clearly |

Adapted from Rosenbaum P: Family-Centered Service. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 18(1):1-20, 1998.

SELECTED RESEARCH EVIDENCE REGARDING FAMILY-CENTERED CARE

Summary of Evidence

Our discussion to this point has focused on the development of the concept of family-centered care. Now we turn to an examination of the empirical evidence regarding this process of care. At first glance, in view of the convincing arguments of the many stakeholders interested in disseminating family-centered care improvements throughout the health care system, the reader might conclude that shifting existing care processes to those that are more family-centered is the most desirable method to successfully support families as they adapt to raising a child with special health care needs. However, before widespread dissemination of any improvement strategy, it is desirable to explore the intervention for the possibility of lack of desired benefit or even potential to harm.29 In addition, understanding how organizational structure affects patient outcomes is important but suffers from a lack of available methods of studying this aspect of care.30 Furthermore, despite the existing literature on family-centered and patient-centered care, commentaries and qualitative studies continue to point out that parents and professionals have limited or conflicting ideas about the meaning and scope of these concepts.31–34

Before discussing the research regarding family-centered care interventions and outcomes, an example involving the “Mr. Yuk” sticker in the childhood poisoning prevention campaign illustrates the importance of empirical evaluation of interventions. “Mr. Yuk,” created by the Pittsburgh Poison Center at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh in 1971, was based on a logical assumption that applying these bright green stickers with a scowling face to bottles of medicines and other potentially toxic substances would help discourage children from ingesting the contents. Distributing these stickers to parents of young children became routine practice in most ambulatory child health care settings after clinicians incorporated the expert recommendation to do so. However, at least two studies35,36 done in the 1980s long after the intervention was entrenched suggested that “Mr. Yuk” stickers do not effectively keep toddlers away from potential poisons and may even attract children to them. One of the studies did note, however, that the stickers might work for older children or as part of a larger poisoning prevention campaign, highlighting the importance of tailoring interventions.36

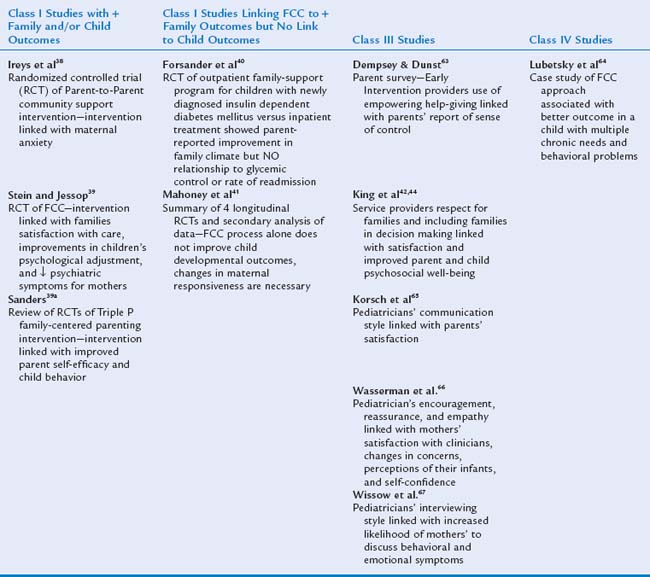

Research linking family-centered care to desired outcomes is available but challenging to summarize as a whole because of the heterogeneity of the definitions of the concept, study populations, focus of investigation, and methodological quality across studies. Furthermore, a complete review of the existing literature on family-centered care is beyond the scope of this chapter. With these limitations in mind, we have chosen to explore several articles linking family-centered care and outcomes and summarized several other articles according to quality of study methodology in Table 8B-3. Evidence is listed alphabetically by author’s names in columns based on the commonly used categorization scheme that organizes studies according to strength of the methodological quality.37 Class I evidence is considered the strongest for drawing valid conclusions between interventions and outcomes and results from randomized controlled trials. Class II evidence is second most powerful and includes nonrandomized trials, before-and-after evaluations, and studies in which participants serve as their own controls. Class III evidence refers to cross-sectional and case-control designs. Class IV evidence, derived from the weakest study designs, pertains to descriptive studies, case reports, and expert opinion. Note that classes III and IV evidence hold value in that they provide starting points for further study and suggested practices in the absence of higher classes of data.

Selected Class I Evidence Regarding Family-Centered Care and Outcomes

Randomized controlled trials of components of family-centered care summarized in the two left columns of Table 8B-3 are described in further detail. Ireys and colleagues evaluated the effect of referral to parent-to-parent support for mothers caring for children with chronic illness and found that mothers in the intervention group had lower anxiety levels, as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory and the Psychiatric Symptom Index.38 Stein and Jessop showed that in a longitudinal family-centered support program for families of CSHCN (the Pediatric Ambulatory Care Treatment Study), the group receiving intervention showed greater satisfaction with care, improvements in children’s psychological adjustment, and fewer psychiatric symptoms for mothers.39 In Australia, Sanders demonstrated in multiple studies the effectiveness of a family-centered parenting intervention, the Positive Parenting Program (Triple-P) for problematic child behaviors.39a Another study done in Sweden with children with newly diagnosed insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus showed associations between outpatient family-centered care processes and parent-reported improvement in family climate but failed to show a relationship to children’s glycemic control or rate of readmission.40 The last report mentioned in the randomized controlled trials in Table 8B-3 is a summary of class I studies that failed to show a simple link between care processes and child outcomes.41 Instead, the authors argued that only if interventions addressed maternal responsiveness were they successful in improving children’s developmental outcomes.

Using the three-level framework conceptualization of family-centered care noted in Table 8B-2, researchers in the Ontario group documented an association between family-centered care for CSHCN and their families in Canadian children’s rehabilitation centers and outcomes such as parent satisfaction with services,42,43 as well as improved parent and child psychosocial well-being.44 In these and other studies listed in Table 8B-3 in the two right columns, the investigators used methods that make it difficult to draw firm conclusions between family-centered care and outcomes. Furthermore, criticisms of using satisfaction and psychosocial well-being as outcomes are derived from the bias presumed inherent in subjective data and the observation that the measurement of traits is more psychometrically reliable than the measurement of states (i.e., satisfaction). In a summary of selected evidence, Rosenbaum found five randomized controlled trials evaluating family-centered care and provided a summary of other pertinent publications, most of who authors had used methods in the class II to class IV categories.28 Shields and associates published a Cochrane Colloquium review protocol for meta-analysis of family-centered care for hospitalized children in 2003 (updated in 2004) but have not begun collecting studies based on the protocol.45 We were not able to find any other publications of controlled trials or meta-analyses pertaining to family-centered care, despite an extensive search.

Other Selected Evidence Regarding Receipt of Family-Centered Care and CSHCN

MCHB, in collaboration with the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, surveyed a nationally representative sample of more than 100,000 households across the country to measure the health and well-being of U.S. children.46,47 The National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), administered to families by telephone, included more than 38,000 families across the United States that had at least one child with special health care need and included questions to measure the six core outcomes listed in Table 8B-4. To assess the progress in achieving their national agenda for CSHCN, the survey included questions regarding families’ perceptions that their care was family-centered. Prevalence estimates from this study showed that 12.8% of children (9.3 million) younger than 18 years need a special health care issue to be addressed. Approximately one third of the families surveyed indicated that they were dissatisfied by the lack of critical elements of family centeredness. Questions regarding family centeredness emphasized the extent to which care provided by the child’s physicians and nurses focused on the family’s needs and not simply the child’s medical condition. Areas addressed included whether the professional (1) met information needs, (2) made the parent feel like a partner, (3) was sensitive to family values and culture, (4) spent enough time, and (5) listened to family concerns. One third of the families reported being usually or always dissatisfied with at least one family-centered aspect of their child’s care. Furthermore, families of such children living in poverty and from minority groups were more likely to be dissatisfied with these aspects of care. Although the data were based on self-report and collected cross-sectionally, which precluded causal conclusions, this study provides an important starting point from which to design more in-depth evaluations of family-centered aspects of the health care system and family health care provider interactions.

TABLE 8B-4 Maternal and Child Health Bureau Core Outcomes for CSHCN

|

All families of CHSCN will have adequate public and/or private health insurance to pay for the services they need.

|

CSHCN, children with special health care needs.

From McPherson M, Weissman G, Strickland BB, et al: Implementing community-based systems of services for children and youths with special health care needs: How well are we doing? Pediatrics 113:1538–1544, 2004.

THE MEDICAL HOME

History and Definition of the Medical Home Concept

The AAP has called for children to have a “medical home” since the 1960s.48 The original 1967 AAP definition referred to a single location of all medical information about a patient, especially children with chronic disease or disabling conditions.49 The idea evolved over the next 35 years to the current one, which emphasizes a concept broader than the notion of a single location. Now the medical home is conceptualized as a quality approach to providing cost-effective primary health care services in which families, health care providers, and related professionals work as partners to identify and access medical and nonmedical services to help children and their families achieve their maximum potential. In 2002, the AAP published a more definitive operational definition clarifying specific activities within each of seven medical home domains: accessible, family-centered, continuous, comprehensive, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective (see Appendix, Chapter 8B for a more complete description of the domains).50–52 Despite progress in clarifying the concept, significant challenges to establishing medical homes for all children remain; an important one is the lack of an adequate reimbursement structure for physicians’ services provided in a medical home. The next section describes a model that has been used to study the implementation of the medical home concept.

Efforts to Promote the Medical Home Concept

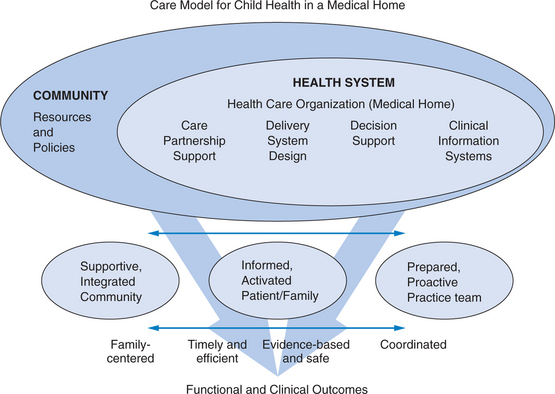

The MCHB funded the National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) to conduct multistate learning collaboratives to help disseminate the medical home concept throughout the United States.52 NICHQ staff and faculty, state Title V leaders, and private practices constituted two consecutive 15-month Medical Home Learning Collaboratives, the first occurring in 2003 to 2004 and the second in 2004 to 2005. The first collaborative included 30 practices in 12 states: Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Louisiana, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin. The second consisted of nine states and multiple practices in the District of Columbia, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont, and West Virginia. The Learning Collaboratives studied the recommended best practices for making changes to enhance care for CSHCN. They employed NICHQ’s framework for improvement, which is based on a synthesis of models from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Breakthrough Series Model,53 the Model for Improvement,54–56 and the Chronic Care Model.57 NICHQ’s model for improvement highlights the need for four key components of practice Microsystems: a clinical information system, effective decision support, a well-designed delivery system emphasizing planned care, and expert support for both family and developmentally appropriate child self-management. The model, schematically represented in Figure 8B-1, also highlights the key role of organizational leadership and the importance of linking health services and community resources.58 The second collaborative used process information regarding what did or did not work from the first learning experience and assessed resulting outcomes occurring as a result of incorporating medical home principles in primary care practices.

FIGURE 8B-1 The care model for child health in a medical home.58

(Adapted from Wagner’s Chronic Care Model in Wagner EH: Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effect Clin Prac 1:2-4, 1998. Reprinted with permission from National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality.)

Select Evidence Regarding Elements of the Medical Home and Outcomes

Documented outcomes from the second NICHQ Medical Home Learning Collaborative included an increase in implementation of medical home concepts in the practices, an improvement in participation of parents in their children’s care, a decrease in unplanned hospitalization rates for CSHCN, a reduction in emergency department visits, decreases in numbers of missed school and work days, and an increase in capability of Title V organizations to implement, spread, and sustain medical home concepts within practices. A report on the implementation process and outcomes can be accessed at NICHQ’s Web site.58

A descriptive study with a screening tool to identify CSHCN59 in primary care settings revealed that the screener has the potential to identify a vulnerable group of children who need comprehensive and coordinated care. An example study of care coordination’s effect on outcomes demonstrated that care coordination was accepted by families and resulted in increased services, but the authors were not able to link the process of coordinating care with the outcomes.60

Practical Suggestions for Practitioners Wishing to Implement a Medical Home