CHAPTER 25 TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY: IMAGING, OPERATIVE AND NONOPERATIVE CARE, AND COMPLICATIONS

The previous chapter described pathophysiology and initial management of traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients. This chapter provides an overview of selected aspects of surgical management, nonoperative care, complications, and outcome.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Brain Swelling

Rapid brain swelling is a major concern after evacuation of an acute SDH. The speed with which this phenomenon occurs suggests that defective autoregulation may play an important role. A popular current practice is simply to leave the native dura open (but loosely cover the brain with a dural graft) and not replace the bone flap. Some neurosurgeons strongly advocate this practice, and it does seem to be effective in lowering intracranial pressure (ICP), but its effects on outcome remain unclear. Publications going back several decades report that a persistent vegetative state was commonly seen in survivors.1 Other concerns are that decompressive craniectomies may be performed too frequently or for poor or inadequate indications. Often, the bony opening that is left behind is too small, causing the swollen brain to strangulate and die, with the resulting edema tracking back intracranially and further aggravating intracranial hypertension.

Implicit in the previous discussion is the need to close the dura before brain swelling makes this impossible. As mentioned previously, this goal may seem antiquated in light of the current popularity of simply not replacing the bone flap. However, the authors have rarely encountered problems using this strategy, even when a retractor had to be used to gently depress swelling brain while the dural edges were forcibly pulled together with forceps so that they could be sutured together. This experience is consistent with laboratory data suggesting that decompressive craniectomy may actually promote cerebral edema.2

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Secondary Insults

The prehospital emphasis on prevention and early treatment of secondary cerebral insults continues during the ICU management of these patients and, in fact, forms the foundation of their management. Special attention should be paid to basic metabolic and physiologic parameters, including blood pressure, oxygenation, hemoglobin concentration, and serum sodium concentration. Surgery for associated injuries that do not absolutely require immediate treatment, such as facial fractures, hand or foot injuries, and even most long-bone fractures, is best deferred while the injured brain is still vulnerable to possible intraoperative metabolic disturbances.

Cerebral Monitoring

ICP monitoring has been widely available for decades. Whenever possible, a ventriculostomy catheter is preferred because of its relatively low cost, its ability to act as a therapeutic tool by draining CSF, and the ability to re-zero the monitor as needed. The development of antibiotic-impregnated catheters seems to have lowered the risk of ventriculostomy infection.3

Intraparenchymal monitors of the oxygen tension of the brain (PbtO2) have generated considerable interest because of the usually good relationship between PbtO2 and cerebral blood flow (CBF). Importantly, interpretation of these data requires knowledge of whether the catheter is measuring normal brain or whether it lies near contused or injured brain. Such positioning dictates whether the catheter is acting like a monitor of global metabolism or a gauge of the regional metabolism of the brain around the probe. Large areas with significantly abnormal regional metabolism may get lost in the background and not be detected if only a global monitor is used. Our preference has been to use local monitors like PbtO2 catheters to target brain tissue around contused or otherwise injured areas.4

Deep Venous Thrombosis

Prevention of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is important in comatose patients who may be bedridden for a prolonged period. Application of sequential compression devices immediately upon patient arrival in the ICU has been effective in our unit. We have not generally used pharmacologic prophylaxis immediately after injury for fear of aggravating potential coagulopathy and possibly contributing to delayed or recurrent intracranial hemorrhage. Occasionally, however, we have added low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) in patients who seemed to be at especially high risk. We have also used LMWH to treat DVT when it occurs. We do not routinely place prophylactic inferior vena cava (IVC) filters. Instead, we have generally reserved IVC filters in TBI patients for cases of documented DVT. We are more aggressive with patients who are paralyzed as a result of a spinal cord injury.

Treatment of Intracranial Hypertension

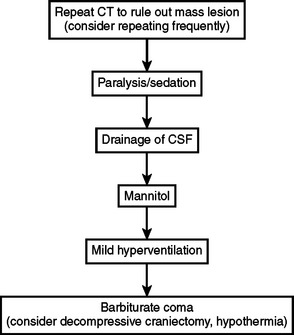

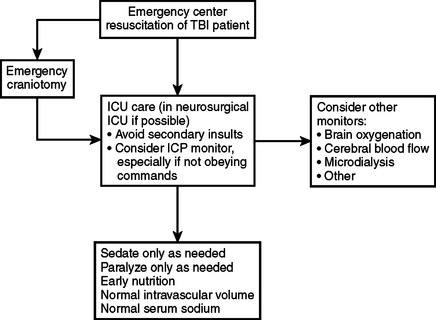

Many algorithms exist for the treatment of elevated ICP (Figure 1). These generally begin with safe, noninvasive interventions. If ICP continues to be elevated, progressively more aggressive treatments are applied. The variety of the algorithms that are available reflects the differences with which various centers embrace the individual treatments that make up those algorithms. Of note, use of steroids to treat TBI is not recommended.

Computed Tomography Scanning

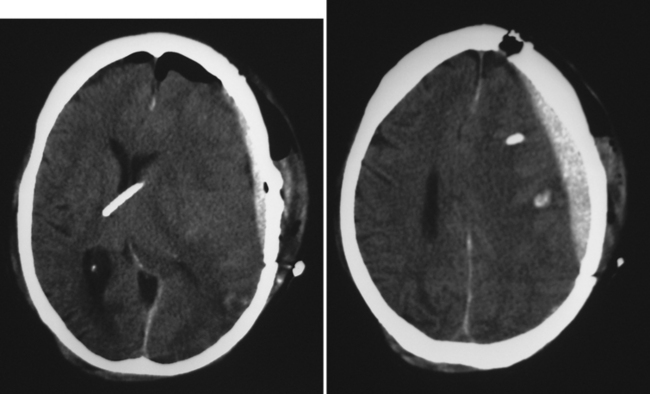

Repeat CT scanning should be considered if there is any suspicion that elevated ICP readings may be caused by a delayed or recurrent hematoma, by hydrocephalus or ventriculostomy malfunction, by a large infarction, and so on (Figure 2).

Sedation and Paralysis

Sedation and analgesics may help to lower ICP, supplemented if needed by neuromuscular blockade.

Cerebrospinal Fluid Drainage

Persistently elevated ICP may respond to CSF drainage if a ventriculostomy has been inserted. The older practice of routinely changing a ventriculostomy catheter every 5–7 days to prevent infection does not seem to be justified by more recent studies,5 and some centers have reported leaving catheters in place for 2 weeks or even longer without an increase in infection rates. The subsequent development of antibiotic-coated ventriculostomy catheters seems to have had a considerable impact on lowering the incidence of ventriculostomy-related infections.6

Osmotic Diuretics

Administration of mannitol is often a useful step. Mannitol has an osmotic effect that pulls fluid from the brain into the vascular compartment. It also decreases blood viscosity, which enables cerebral arteries to constrict (and thereby lower intracerebral blood volume) without decreasing CBF because the decrease in viscosity facilitates adequate flow through the narrower artery.7 Hypertonic saline is receiving a great deal of interest as a possible surrogate or supplement to mannitol. Its use has become especially widespread among pediatric intensivists. Although preliminary reports are encouraging, more solid data are still pending about the optimal method of administration and about relative indications, contraindications, and adverse events.

Barbiturate Coma

Persistent intracranial hypertension may respond to pentobarbital-induced coma.8 This treatment is effective at lowering ICP, but hypotension is a major problem. Prior to administering barbiturates, we usually insert a pulmonary artery catheter to ensure that intravascular volume is adequate. Likewise, we have pressors ready for immediate infusion if the blood pressure begins to decrease.

Decompressive Craniectomy

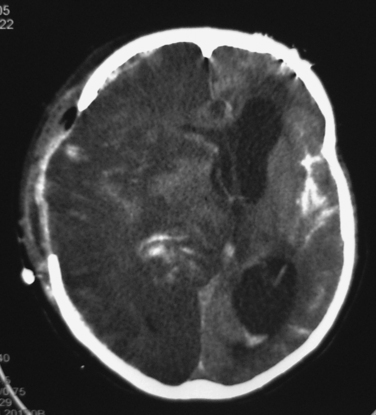

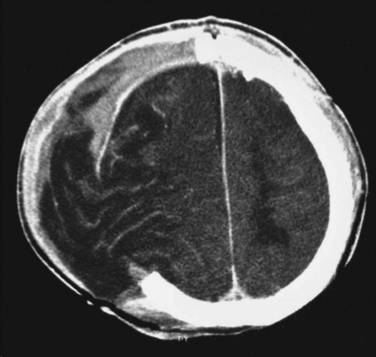

Intracranial hypertension that persists despite initiation of the treatments listed in Figure 1 is a serious problem. Decompressive craniectomy, in which a large part of the skull is temporarily removed so that the injured brain has room to swell, is currently a popular intervention. It seems clear that a large craniectomy can lower ICP, but uncertainty remains about whether it improves patient outcomes. It is possible that many of these operations are performed prematurely and/or with inadequate removal of bone (Figure 3). The complications of decompressive craniectomy can also be troubling, including development of contralateral subdural fluid collections and herniation of brain through the craniectomy defect (Figure 4).

Hypothermia

Another potential treatment is hypothermia. The results of the National Acute Brain Injury Study: Hypothermia demonstrated lack of effect when this treatment was applied indiscriminately to all patients.9 However, like decompressive craniectomy or any other intervention, it is likely that a specific subpopulation of TBI patients can benefit. The difficulty for investigators and clinicians lies in identifying patients for whom an intervention has the most optimal benefit:risk ratio.

MORBIDITY AND COMPLICATIONS

Rebleeding or delayed intracranial bleeding can be catastrophic (see Figure 2). Some of these events may be caused by suboptimal surgical technique in which inadequate time was spent ensuring that hemostasis was present. Often, however, patients may have a pre-existing history of liver disease, and the trauma itself can predispose to a coagulopathic state. Aggressive use of fresh frozen plasma and sometimes platelets may help achieve hemostasis in patients with persistent diffuse oozing. Recent reports describing the successful use of recombinant factor VIIa in such cases have generated considerable interest.

MORTALITY

Unfortunately, mortality rate at hospital discharge is a poor outcome measure for TBI. Survival is not considered to be a good outcome if a patient will remain in a persistent vegetative state. Most TBI studies have considered death, persistent vegetative state, or severe disability to be a poor outcome, whereas good recovery or moderate disability has been viewed as a good outcome. These outcome categories are based on the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) (Table 1). In addition or instead of the GOS, some studies use more detailed instruments to assess outcome, especially if data are sought about less obvious measures, such as neuropsychological function.

| Score | Category | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Good recovery (GR) | Able to live and work independently despite minor disabilities. |

| 4 | Moderate disability (MD) | Able to live independently despite disabilities. Can use public transportation, work with assistance/supervision, and so on. |

| 3 | Severe disability (SD) | Conscious but dependent on others for self-care. Often institutionalized. |

| 2 | Persistent vegetative state (PVS) | Not conscious, but may appear “awake.” |

| 1 | Death (D) | Self-explanatory. |

CONCLUSIONS AND ALGORITHM

Figure 5 lists some basic principles and goals in the management of TBI patients. As always, the main goal remains the avoidance of secondary insults. The best monitor is a reliable neurologic examination repeated at regular intervals. Patients who do not obey commands may require monitoring of ICP and other parameters to facilitate prompt detection of adverse metabolic events. Generic algorithms are available for the treatment of intracranial hypertension (see Figure 1). Patient-specific interventions may supplement or replace these algorithms if monitoring data suggest the existence of particular pathophysiologic patterns in given patients.

1 Cooper PR, Rovit RL, Ransohoff J. Hemicraniectomy in the treatment of acute subdural hematoma: a re-appraisal. Surg Neurol. 1976;5:25-28.

2 Cooper PR, Hagler H, Clark WK, Barnett P. Enhancement of experimental cerebral edema after decompressive craniectomy: implications for the management of severe head injuries. Neurosurgery. 1979;4:296-300.

3 Zabramski JM, Whiting D, Darouiche RO, et al. Efficacy of antimicrobial-impregnated external ventricular drain catheters: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:725-730.

4 Gopinath SP, Valadka AB, Uzura M, Robertson CS. Comparison of jugular venous oxygen saturation and brain tissue PO2 as monitors of cerebral ischemia after head injury. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2337-2345.

5 Holloway KL, Barnes T, Choi S, et al. Ventriculostomy infections: the effect of monitoring duration and catheter exchange in 584 patients. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:419-424.

6 Muizelaar JP, Wei EP, Kontos HA, Becker DP. Mannitol causes compensatory cerebral vasoconstriction and vasodilation in response to blood viscosity changes. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:822-828.

7 Eisenberg HM, Frankowski RF, Contant CF, et al. High-dose barbiturate control of elevated intracranial pressure in patients with severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:15-23.

8 Clifton GL, Miller ER, Choi SC, et al. Lack of effect of induction of hypothermia after acute brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:556-563.

9 Marshall LF, Gautille T, Klauber MR, et al. The outcome of severe closed head injury. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:S28-S36.