CHAPTER 7 TRAUMA SYSTEMS AND TRAUMA TRIAGE ALGORITHMS

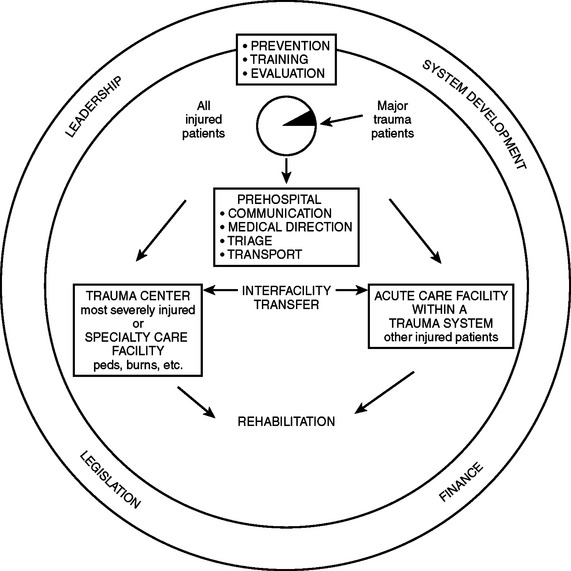

Trauma is a major national health care problem that affects one of four U.S. citizens annually. Traumatic injury, both accidental and intentional, is the leading cause of death in the United States for people aged 1 to 34 years. There are as many as 150,000 trauma deaths and approximately 80,000 others who sustain long-term disability each year with annual costs of more than $260 billion for trauma injury and treatment when loss of future productivity is considered. The most common fatal injuries in the country result form motor vehicle crashes, followed closely by gunshot wounds. Driving while impaired by alcohol is the most frequent cause of fatal motor vehicle crashes and accounts for 40% of traffic fatalities. The causes of traumatic death vary considerably depending on demographics. Urban and politically unstable areas typically have a higher incidence of penetrating trauma, whereas rural and stable communities have a predominance of blunt injuries, usually vehicular accidents. Nonetheless, causes of death after injury are remarkably similar. Central nervous system injury accounts for approximately half of all fatalities; hemorrhage for 35%; and sepsis, multiple organ failure, and pulmonary embolism combine for approximately 15%. With the introduction of trauma systems during the last three decades, the incidence of preventable death has dropped from approximately 25% to less than 5%. This is the result of improvements in care both for acute head injuries and for control of hemorrhage. In addition, the incidence of late death attributable to sepsis and multiple organ failure has diminished, possibly as a result of better and early resuscitation. The responsibility of the trauma surgeon encompasses the early recognition of injury, resuscitation, and then definitive care of the patient. As we improve the operative and intensive care rendered to trauma patients, we are beginning to reach the flat portion of the outcome curve. The area of injury prevention is still open to substantial improvement. To reduce the morbidity and mortality from trauma, surgeons must take a more active role in the prevention of trauma at the community level. Studies have shown the effect of these systems on the improvement of trauma care, with outcomes better than those predicted for some study populations. The necessary elements of a trauma system have been defined. These include four primary patient needs—access to care, prehospital care, hospital care, and rehabilitation. In addition, five issues require social and political solutions to supplement medical efforts: prevention, disaster medical planning, patient education, research, and rational financial planning. Recent federal legislation (The Trauma Care Systems Planning and Development Act) authorized planning, implementation, and development of statewide trauma care systems.

TRAUMA SYSTEMS

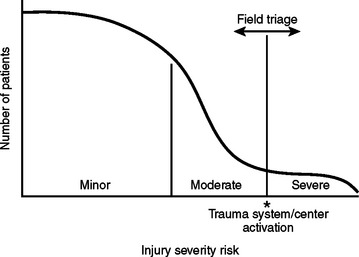

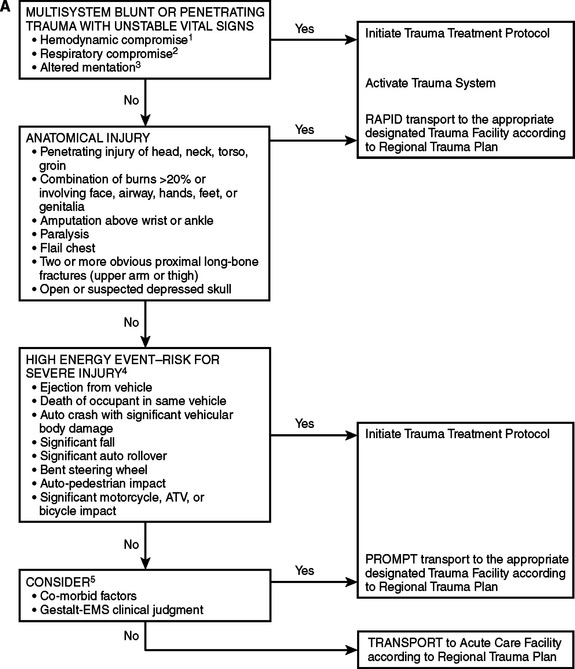

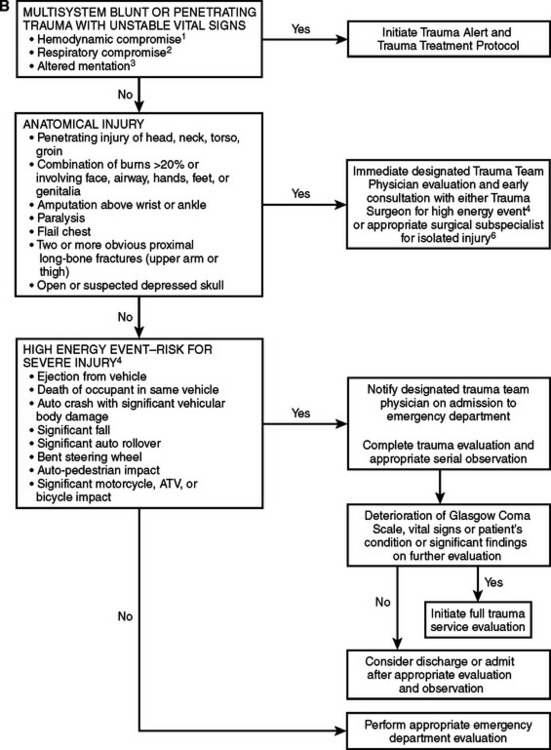

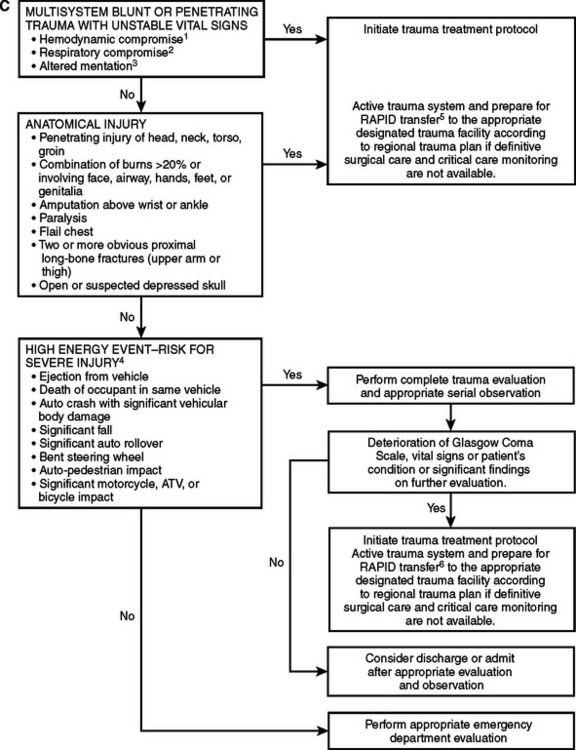

Major trauma patients are those with either a severe injury or a risk for severe injury. A severe injury is one that could result in morbidity or mortality, and is classically defined as an injury with an Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 16 or higher. On initial evaluation, these patients typically have abnormal vital signs or a significant anatomical injury. However, triage is often inexact due to patients’ variable physiological responses to trauma. In some patients, minor injuries can result in morbidity or mortality due to the patient’s age and/or comorbid factors, and some patients may have a delayed physiological response to trauma. Patients involved in a high-energy event are at risk for severe injury. Five to 15% of these patients, despite normal vital signs and no apparent anatomical injury on initial evaluation, will have a severe injury discovered after full trauma evaluation with serial observations (Figure 1).

Current systems (“exclusive systems”) often rely on overtriage to trauma centers, and often an exaggerated and unnecessary response from trauma professionals. Such systems may cause overtreatment of certain patients, unnecessary expenses, burnout of participants, and underutilization of certain health care resources, including personnel. In spite of these excesses, such systems may still run the risk of not treating all injured patients, including not appropriately treating all major trauma patients. Undertriage runs the obvious risk of excluding some major trauma patients from receiving appropriate care. An inclusive system uses a tiered response to provide appropriate delivery, evaluation, and care for all patients, including the major trauma patient, in a cost-effective manner. One example of an inclusive trauma system is patient triage designed to care for major trauma patients by matching patient severity to facility in a timely manner. Considerations in triage include injury severity, injury severity risk, time and distance from site of injury to definitive care, inter-hospital transfers considering guidelines for immediate versus postintervention transports, and factors that activate the regional system (Figure 2).

SUPPORT FOR REGIONALIZED TRAUMA CARE

Although regionalization of trauma care has the inevitable consequence of increased prehospital transport times, particularly in rural areas removed from large trauma centers, some states have designed inclusive systems in which a large number of smaller centers have been designated as lower-level trauma centers. One of the primary functions of a statewide trauma system is to oversee the initiation of standardized protocols intended to ensure the timely triage and transfer of severely injured patients to facilities with appropriate therapeutic resources. Several studies document increased trauma center use and enhanced patient outcomes among metropolitan trauma centers after implementation of a regionalized trauma system.

INITIAL APPROACH TO THE CRITICALLY INJURED PATIENT

Prehospital Care: Intervention at Injury Site

Resuscitation and evaluation of the trauma patient begins at the injury site. The goal is to get the right patient to the right hospital at the right time for definitive care. First responders (typically, firefighters and police) provide rapid basic trauma life support (BTLS) and are followed by paramedics and fight nurses with advanced trauma life support (ATLS) skills. Medical control is ensured by pre-established field protocols, radio communication with a physician at the base hospital, and subsequent trip audits. Management priorities of BTLS on the scene are (1) to access and control the scene for the safety of the patient and the prehospital care providers, (2) to tamponade external hemorrhage with direct pressure, (3) to protect the spine after blunt trauma, (4) to clear the airway of obstruction and provide supplemental inspired oxygen, (5) to extricate the patient, and (6) to stabilize long-bone fractures. Whereas the benefits of BTLS are undisputed, the merits of the more advanced interventions remain controversial.1,2 Airway access, once considered a major asset of the care provided by paramedics and flight nurses, has now been questioned, not only because missed tracheal intubation is a concern but also because unintentional hyperventilation (hypocarbia) is detrimental in the setting of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).3–5 Moreover, the value of intravenous fluid administration remains controversial.6,7

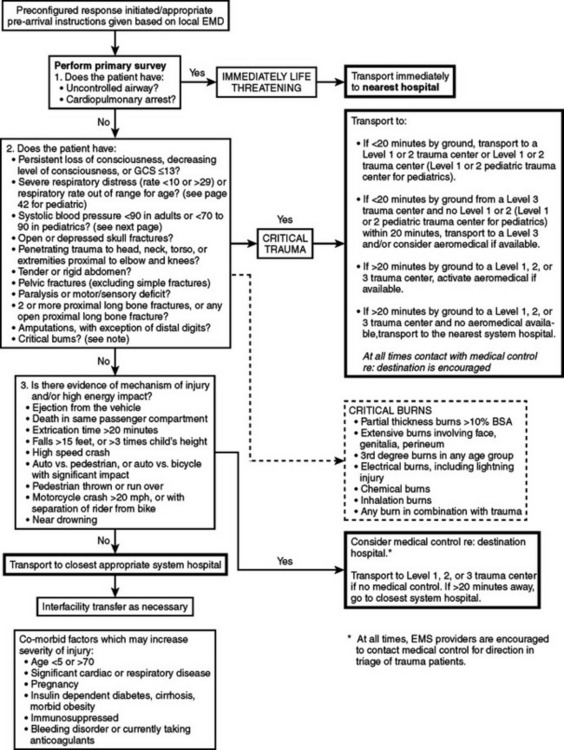

Field Triage

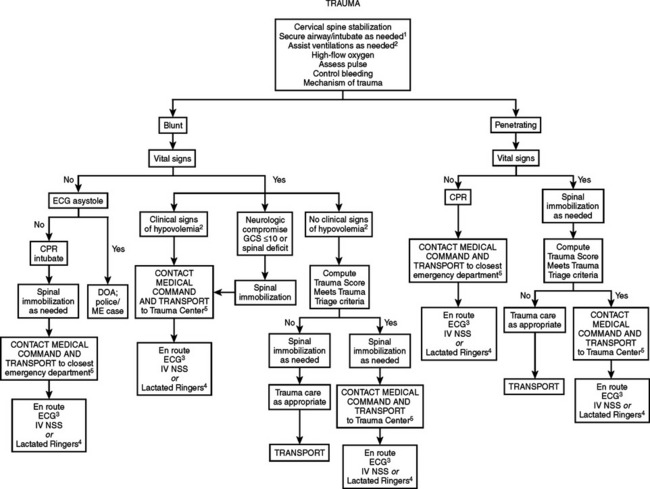

Prehospital trauma scores have been devised to identify critically injured trauma victims, who represent about 10%–15% of all injured patients. When it is geographically and logistically feasible, critically injured patients should be taken directly to a designated Level I trauma center or to a Level II trauma center if a Level I trauma center is more than 30 minutes away. The currently available field trauma scores, however, are not entirely reliable for identifying critically injured patients8: to capture a sizable majority of patients with life-threatening injuries, a 50% overtriage is probably necessary. Advance transmission of key patient information to the receiving trauma center facilitates the organization of the trauma team and ensures the availability of ancillary services9 (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3 Trauma field triage criteria and point-of-entry plan for adult patients.

(From Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Department of Public Health.)

Figure 4 Adult triage, transport, and transfer guidelines: Oklahoma model trauma triage algorithms for (A) prehospital, (B) Level I/II trauma center, and (C) Level III/IV trauma center. For prepubescent patients, refer to the pediatric trauma algorithm (Figure 5). 1. In addition to hypotension, other early signs of hypovolemia may include pallor, tachycardia, or diaphoresis. 2. Tachypenia (hyperventilation) alone will not necessarily initiate this level of response. 3. Altered sensorium secondary to sedative-hypnotic will not necessarily initiate this level of response. 4. High-energy event signifies a large release of uncontrolled energy. Patient is assumed injured until proven otherwise, and multisystem injuries might exist. Determinants to be considered by medical professionals are direction and velocity of impact, patient kinematics and physical size, and the residual signature of energy release (e.g., major vehicle damage). 5. Clinical judgment must be exercised and may upgrade to a high level of response and activation. Age and comorbid conditions should be considered in the decision. 6. Isolated blunt or penetrating trauma not associated with a high-energy event with a potential for multisystem injury.

(Based on American College of Emergency Physicians Guidelines. Approved by the Triage, Transport, and Transfer Committee of the Oklahoma State Trauma Advisory Council, October 27, 1995, and the Oklahoma Emergency Medical Services Advisory Council on January 24, 1997.)

GUIDELINES FOR WITHHOLDING OR TERMINATION OF RESUSCITATION IN PREHOSPITAL CARDIOPULMONARY ARREST

Injury is the leading cause of death for Americans between age 1 and 44 years. The EMS system is the portal into the medical system for many of the most seriously injured trauma victims. Some of these patients will be unsalvageable due to the extent of their injuries. In order to preserve dignity and conserve precious human and financial resources, as well as to minimize risks to the health care workers involved, patients who can be predicted to be unsalvageable should not be transported emergently to the emergency department (ED) or trauma center. The National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP) and the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (COT) support out-of-hospital withholding or termination of resuscitation for adult traumatic cardiopulmonary arrest (TCPA) patients who meet specific criteria. The literature review of prehospital TCPA is extrapolated from emergency thoracotomy research. This research is retrospective in nature, therefore limiting the validity of the conclusions. The guidelines appear in Table 1.

Table 1 Guidelines for Withholding or Termination of Resuscitation in Prehospital Cardiopulmonary Arrest

| Resuscitation efforts may be withheld in any blunt trauma patient who, based on out-of-hospital personnel’stient assessment, is found apneic, pulseless, and without organized ECG activity upon the arrival of EMS at the scene. |

| Victims of penetrating trauma found apneic and pulseless by EMS, based on their patient assessment, should be rapidly assessed for the presence of other signs of life, such as papillary reflexes, spontaneous movement, or organized ECG activity. If any of these signs are present, resuscitation should be performed and the patient transported to the nearest emergency department or trauma center. If these signs of life are absent, resuscitation efforts may be withheld. |

| Resuscitation efforts should be withheld in victims of penetrating or blunt trauma with injuries obviously incompatible with life, such as decapitation or hemi-corpectomy. |

| Resuscitation efforts should be withheld in victims of penetrating or blunt trauma with evidence of a significant time lapse since pulselessness, including dependent lividity, rigor mortis, and decomposition. |

| Cardiopulmonary arrest patients in whom the mechanism of injury does not correlate with clinical condition, suggesting a nontraumatic cause of the arrest, should have standard resuscitation initiated. |

| Termination of resuscitation efforts should be considered in trauma patients with EMS-witnessed cardiopulmonary arrest and 15 minutes of unsuccessful resuscitation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). |

| Traumatic cardiopulmonary arrest patients with transport time to an emergency department or trauma center of more than 15 minutes after the arrest is identified may be considered nonsalvageable, and termination of resuscitation should be considered. |

| Guidelines and protocols for TCPA patients who should be transported must be individualized for each EMS system. Consideration should be given to factors such as the average transport time within the system, the scope of practice of the various EMS providers within the system, and the definitive care capabilities (trauma centers) within the system. Airway management and intravenous line placement should be accomplished during transport when possible. |

| Special consideration must be given to victims of drowning and lightning strike and in situations where significant hypothermia may alter prognosis. |

| EMS providers should be thoroughly familiar with the guidelines and protocols affecting the decision to withhold or terminate resuscitative efforts. |

| All termination protocols should be developed and implemented under the guidance of the system EMS medical director. On-line medical control may be necessary to determine the appropriateness of terminating resuscitation. |

| Policies and protocols for terminating resuscitation efforts must include notification of the appropriate law enforcement agencies and notification of the medical examiner or coroner for final disposition of the body. |

| Families of the deceased should have access to resources, including clergy, social workers, and other counseling personnel, as needed. EMS providers should have access to resources for debriefing and counseling as needed. |

| Adherence to policies and protocols governing termination of resuscitation should be monitored through a quality review system. |

Initial Electrocardiographic Rhythm

There is some evidence that the initial ECG rhythm obtained at the scene by EMS may be predictive of survival. All of the studies combined by Batistella et al.,10 Fulton et al., Esposito et al.,9 and Aprahamian suggest that the presence of an ECG rhythm such as asystole, idioventricular rhythm, or severe bradycardia is indicative of an unsalvageable patient. Patients with a sinus-based pulseless electrical activity may represent a potentially salvageable subset of TCPA patients. Given that the TCPA is a critical event, the presence of any abnormal ECG pattern as an indicator of survival has limited significance. Blunt and penetrating injury as the cause of the TCPA was not distinguished in these studies, and given that blunt injury causing TCPA is associated with a very poor survival rate, it may be that survivors of TCPA may have penetrating trauma as their inciting event.

PREHOSPITAL CARE CONTROVERSIES

Advanced Trauma Life Support

The growing sophistication of emergency medical services has expanded the scope of prehospital care, but the extent of prehospital interventions remains a highly controversial issue. In trauma, advocates of the so-called scoop-and-run philosophy argue that resuscitative efforts in the field unnecessarily delay provision of definitive care and have detrimental effects on physiology and survival when overzealously applied. At present, there is little evidence to support the use of ATLS in prehospital management of urban trauma patients. ATLS skills may be of value in rural areas where transport time exceeds 30 minutes, but unfortunately, the limited volume of serious trauma in such areas makes it difficult to gain the experience necessary to maintain this expertise.

Prehospital Intubation of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury

Because hypoxia has been associated with increased mortality in patients with TBI, aggressive prehospital airway protocols that include rapid sequence intubation have been instituted. This practice may, however, be associated with worse outcomes.3

Resuscitation with Hypertonic Saline

Small-volume hypertonic saline (HS) has been shown to be as effective as large volume crystalloid in expanding plasma volume and enhancing cardiac output. HS increases perfusion of the microcirculation by inducing selective arteriolar vasodilation and by reducing the swelling of red blood cells and endothelium, at the expense of possibly increasing bleeding. HS combined with HS dextran (HSD) may have improved resuscitative effects. Trials comparing HS to HSD have shown inconsistent results with respect to improved survival, yet confirming that a bolus of either fluid was safe. Subgroup analysis of these studies showed that patients who presented with shock and concomitant severe TBI benefited the most from HSD. In comparison to isotonic saline, both HS and HSD raised cerebral perfusion pressure, lowered intracranial pressure, and reduced brain edema.

PEDIATRIC TRAUMA SYSTEM

Injury is the leading cause of death in children older than 1 year. In 2001, more than 5500 children younger than 15 years died as a result of injuries. Another 1000 died because of violent deaths, the result of homicide or suicide. With respect to nonfatal injuries, in 2002, more than 100,000 children were hospitalized, and more than 6 million children were evaluated in emergency departments after sustaining an injury. Falls are the most common mechanism of injury and motor vehicle crashes are the most deadly, accounting for 30%–60% of traumatic pediatric deaths. Trauma systems, pediatric trauma centers (PTCs), and caregivers who are specifically trained to treat children are all components of a system of care designed to provide better outcomes for patients. Regional PTCs were established to optimize the care of injured children. However, because of the relative shortage of PTCs, many injured children continue to be treated in adult trauma centers (ATCs). It is well known that the geographic distribution of trauma centers results in a significant number of children being treated in adult centers with various ACS designations.15 As a result, growing controversy has evolved regarding the impact of PTCs and ATCs on outcome for injured children. Many medical facilities are not adequately staffed or equipped with the necessary resources to optimally care for severely injured pediatric trauma victims.

An EMSC sponsored APSA study published in 2005 demonstrated that injured children have better outcomes when trauma care is received at a designated children’s hospital. Densmore et al.17 used the 2000 Kid’s Inpatient Database (part of the Health Care Cost and Utilization Project sponsored by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality) to describe pediatric trauma patient allocation to hospitals and associated injury outcomes. Approximately 80,000 pediatric trauma cases from 27 states were analyzed. The authors concluded that younger and more severely injured children have improved outcomes in children’s hospitals.

Potoka et al.12 analyzed 13,351 injured children from the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcome Study between 1993 and 1997. With mortality as the major outcome variable, cases were evaluated and compared based on type of trauma center: PTC, Level I ATC (ATC I), Level II ATC, or an ATC with added qualification to treat children (ATC AQ). They reported that most injured children were treated at a PTC or an ATC AQ and that most children younger than 10 years were admitted to a PTC. Overall survival was significantly better at a PTC and an ATC AQ compared with an ATC I and a Level II ATC. Survival for head, spleen, and liver injuries was significantly better at a PTC compared with all other destinations combined. Children who sustained moderate or severe head injuries were most likely to undergo neurosurgical intervention and have a better outcome when treated at a PTC. Despite similar mean AISs for spleen and liver trauma, significantly more children underwent surgical exploration (especially splenectomy) for spleen and liver injuries at an ATC compared with a PTC. Nonoperative management of splenic and hepatic injuries decreases the potential morbidities of surgical therapy and postsplenectomy sepsis. They concluded that pediatric commitment in a Level I trauma center results in nonoperative treatment of injured children commensurate with that established in regional PTCs. The authors concluded that children treated at a PTC or ATC-AQ have significantly better outcomes compared to those treated at an ATC. In addition, ACS-verified centers had significantly higher survival rates compared with unverified centers. Severely injured children (ISS >15) with head, spleen, or liver injuries had the best overall outcome when treated at a PTC. This difference in outcome may be attributable to the approach to operative and nonoperative management of head, liver, and spleen injuries at PTCs.

Pediatric patients with severe TBI are more likely to survive if treated in PTCs or ATC AQs, rather than in Level I or Level II ATCs.

Pediatric patients with severe TBI are more likely to survive if treated in PTCs or ATC AQs, rather than in Level I or Level II ATCs. The pediatric patient with severe TBI who requires neurosurgical procedures has a lower chance of survival in Level II ATCs versus the other centers.

The pediatric patient with severe TBI who requires neurosurgical procedures has a lower chance of survival in Level II ATCs versus the other centers. In 2001, Osler et al.19 reviewed 53,113 pediatric trauma cases from 22 PTCs and 31 ATCs included in the National Pediatric Trauma Registry to evaluate survival rates. They reported the overall mortality rate to be lower at PTCs (1.81% of 32,554 children) than at ATCs (3.88% of 18,368 children). The authors concluded that although PTCs have higher overall survival rates compared with ATCs, the difference disappears when the analysis controls for ISS, Pediatric Trauma Score, age, mechanism, and ACS verification status.

In 2001, Osler et al.19 reviewed 53,113 pediatric trauma cases from 22 PTCs and 31 ATCs included in the National Pediatric Trauma Registry to evaluate survival rates. They reported the overall mortality rate to be lower at PTCs (1.81% of 32,554 children) than at ATCs (3.88% of 18,368 children). The authors concluded that although PTCs have higher overall survival rates compared with ATCs, the difference disappears when the analysis controls for ISS, Pediatric Trauma Score, age, mechanism, and ACS verification status. In 1994, Bensard et al.18 sought to critically evaluate the outcome of injured children treated in an ATC I by adult trauma surgeons. The probability of survival was calculated using TRISS methodology. They found that the observed survival (98.0%) in children compared favorably with the TRISS-predicted survival (97.7%), and showed no difference in relative risk for acutely injured children (+0.47) compared with young adults (+0.45) or national norms such as the Major Trauma Outcomes Study (MTOS) reference set. They concluded that the triage of injured children to an ATC I does not adversely affect outcome. However, there are limitations when applying the TRISS methodology to children which include very few pediatric patients in the original data set, elements of the physiological data which use adult norms and not pediatric norms, and finally, the MTOS-derived data from 1982 to 1989 may be questionable, as injury rates declined from 1990 to 2005. These data support the continued triage of acutely injured children to regional trauma centers regardless of pediatric or adult designation.

In 1994, Bensard et al.18 sought to critically evaluate the outcome of injured children treated in an ATC I by adult trauma surgeons. The probability of survival was calculated using TRISS methodology. They found that the observed survival (98.0%) in children compared favorably with the TRISS-predicted survival (97.7%), and showed no difference in relative risk for acutely injured children (+0.47) compared with young adults (+0.45) or national norms such as the Major Trauma Outcomes Study (MTOS) reference set. They concluded that the triage of injured children to an ATC I does not adversely affect outcome. However, there are limitations when applying the TRISS methodology to children which include very few pediatric patients in the original data set, elements of the physiological data which use adult norms and not pediatric norms, and finally, the MTOS-derived data from 1982 to 1989 may be questionable, as injury rates declined from 1990 to 2005. These data support the continued triage of acutely injured children to regional trauma centers regardless of pediatric or adult designation.Conclusions

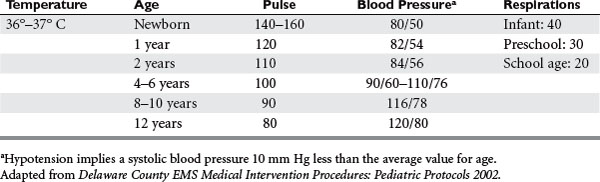

With the regionalization of designated pediatric subspecialty and trauma care centers and the triaging of injured children to appropriate designations, pediatric trauma systems in the United States are becoming valuable tools in the optimum care of injured children. However, with the specialization of pediatric trauma care systems still in its infancy, the triage of all injured children to regional PTCs may be impractical and may unnecessarily exclude Level I ATCs from the care of acutely injured children. Ongoing studies on pediatric trauma, including measures of morbidity and functional outcomes, are needed to further define the optimal models and systems for trauma care. PTCs are the only institutions with the pediatric trauma volumes necessary for the study of outcome measures, and with the capabilities to take the initiative in the study injury prevention (Figure 5 and Table 2).

PRACTICE MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES FOR GERIATRIC TRAUMA

Triage Issues in Geriatric Trauma

Statement of the Problem

Issues to define include the following:

| Level I | There are insufficient class I and class II data to support any standards regarding triage of geriatric trauma patients. |

| Level II | Advanced patient age should lower the threshold for field triage directly to a trauma center. |

| Level III | Advanced patient age is not predictive of poor outcomes following trauma, and therefore should not be used as the sole criterion for denying or limiting care in this patient population. |

| The presence of pre-existing medical conditions in elderly trauma patients adversely affects outcome. | |

| In patients 65 years of age and older, a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 8 is associated with a dismal prognosis. If substantial improvement in GCS is not realized within 72 hours of injury, consideration should be given to limiting further aggressive therapeutic interventions. | |

| Postinjury complications in the elderly trauma patient negatively impact survival and contribute to longer lengths of stay in survivors and nonsurvivors compared to younger trauma patients. | |

| With the exception of patients who are moribund on arrival, an initial aggressive approach should be pursued with the elderly trauma patient, as the majority will return home, and up to 85% will return to independent function. | |

| In patients 55 years of age and older, an admission base deficit 6 is associated with a 66% mortality. Patients in this category may benefit from inpatient triage to a high-acuity nursing unit. | |

| In patients 65 years of age and older, a Trauma Score 7 is associated with a 100% mortality. Consideration should be given to limiting aggressive therapeutic interventions. | |

| In patients 65 years of age and older, an admission respiratory rate 10 is associated with a 100% mortality. Consideration should be given to limiting aggressive therapeutic interventions. | |

| Compared to younger trauma patients, patients 55 years of age and older are at considerably increased risk for undertriage to trauma centers even when these older patients satisfy appropriate triage criteria. The factors responsible for this phenomenon must be identified and strategies developed to counteract it. |

Scientific Foundation

For the geriatric trauma patient, the process begins in the prehospital arena, where prehospital providers must decide on the basis of relatively scant clinical information whether a patient should bypass the local hospital in favor of a trauma center. The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS-COT), among other medical organizations, in its manual “Optimal Resources for the Care of the Trauma Patient,” has published a set of triage criteria to aid prehospital providers in identifying appropriate patients for direct transport to trauma centers.1 Within this document, it is suggested that patients aged over 55 should be “considered” for direct transport to a trauma center, apparently without regard to the severity of injury. This recommendation is based on a substantial medical literature that demonstrates significantly worse outcomes for geriatric trauma patients compared to their nongeriatric counterparts.

Predictors of Mortality in Geriatric Population

Severity of Injury Scoring and Outcome

The ISS is probably the most widely studied anatomic or physiologic severity of illness score yet to be correlated with geriatric trauma outcome. Its use as a predictor of outcome and mortality in geriatric are inconclusive. ISS is severely limited in its prognostic capability due to significant delays in obtaining sufficient data to calculate the score.

Parameters for Resuscitation of the Geriatric Trauma Patient

The evidence-based recommendations in Table 4 will provide the trauma practitioner a guide to decision making in the resuscitation phase of care of the geriatric patient.

Table 4 Evidence-Based Recommendations for Decision Making in Resuscitation Phase of Care of the Geriatric Patient

| Level I recommendations: | There are insufficient data to support a Level I recommendation for endpoints of resuscitation in the elderly patient as a standard of care. |

| Level II recommendations: | Any geriatric patient with physiologic compromise, significant injury (Abbreviated Injury Scale [AIS] >3), high-risk mechanism of injury, uncertain cardiovascular status, or chronic cardiovascular or renal disease, should undergo invasive hemodynamic monitoring using a pulmonary artery catheter. |

| There are insufficient data to support a Level I recommendation for endpoints of resuscitation in the elderly patient as a standard of care. | |

| Level III recommendations: | Attempts should be made to optimize to a cardiac index 4 l/min/m2 and/or an oxygen consumption index of 170 cc/min/m2. |

| Base deficit measurements may provide useful information in determining status of resuscitation and risk of mortality. |

Summary

While multiple clinical and demographic factors have demonstrated an association with outcome following trauma in geriatric patients, the ability of any specific factor alone, or in combination with other factors, to predict an unacceptable outcome for any individual geriatric trauma patient is quite limited. An initial course of aggressive therapy seems warranted in all geriatric trauma patients, regardless of age or injury severity, with the possible exception of those patients who arrive in a moribund condition. Geriatric trauma patients who do not respond to aggressive resuscitative efforts within a timely fashion are likely to have poor outcomes even with continued aggressive treatment. Modification of the intensity of treatment provided to these “nonresponders” should be considered. For geriatric trauma patients who do respond favorably to aggressive resuscitative efforts, the prognosis, not only for survival but also for return to their preinjury level of function, is quite good, and certainly justifies the effort.

CONCLUSION

The benefits of successful implementation of this plan include the following:

Increase in the number of productive working years seen in the United States through reduction of death and disability

Increase in the number of productive working years seen in the United States through reduction of death and disability Decrease in the costs associated with initial treatment and continued rehabilitation of trauma victims

Decrease in the costs associated with initial treatment and continued rehabilitation of trauma victimsAprahamian C, Thompson BM, Gruchow HW, Mateer JR, Tucker JF, Stueven HA, Darin JC. Decision-Making in pre-hospital sudden cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(4):445-449.

Batistella FD, et al. Trauma patients 75 years and older: long-term follow-up results justify aggressive management. J Trauma. 1998;44:618-624.

Bensard DD, et al. A critical analysis of acutely injured children managed in an adult Level 1 trauma center. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:11-18.

Delaware County EMS Medical Intervention Procedures II. Pediatric Protocols. Rev.. December 15, 2002.

Densmore, et al. Outcomes and delivery of care in pediatric injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:92-98.

EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group. Practice Management Guidelines for Geriatric Trauma. East Northport, NY: Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, 2001.

Esposito TH, et al. Do pre-hospital trauma center triage criteria identify major trauma victims? Arch Surg. 1995;130:171-176.

Fulton RL, Voigt WJ, Hilakos AS. Confusion surrounding the treatment of traumatic cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:209-214.

Gaines BA. Pediatric trauma care: an ongoing evolution. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2005;6:4-7.

Hannan EL, Farrell LS, Cooper A, Henry M, et al. Physiologic trauma triage criteria in adult trauma patients: are they effective in saving lives by transporting patients to trauma centers? J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:584-592.

Hopson LR, Hirsh E, Delgado J, Domeier RM, et al. Guidelines for Withholding or Termination of Resuscitation in Prehospital Traumatic Cardiopulmonary Arrest: Joint Position Statement of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Lenexa, KS: National Association of EMS Physicians, 2003.

Hoyt DB, Coimbra R. Trauma systems. In: Greenfield LJ, editor. Surgery: Scientific Principles and Practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001:280-283.

Junkins EP, O’Connell KJ, Mann NC. Pediatric trauma systems in the United States: do they make a difference? Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2006;7(2):76-81.

Khan CA, et al. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Notes. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(6):212.

MacKenzie EJ, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:366-378.

DA Margolin, DJ Johan & WF Fallon: Response After Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest in the Trauma Patient Should Determine Aeormedical Transport to a Trauma Center

Mullins RJ, Mann NC. Population-based research assessing the effectiveness of trauma systems. J Trauma. 1999;47:S34-S41.

Osler TM, et al. Do pediatric trauma centers have better survival rates than adult trauma centers? An examination of the National Pediatric Trauma Registry. J Trauma. 2001;50:96-101.

Peterson TD, Vaca F. Commentary: trauma systems: a key factor in homeland preparedness. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(6):799-801.

Potoka DA, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma in the pediatric patient. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2005;6:23-31.

Reilly JJ, et al. Use of a statewide administrative database in assessing a regional trauma system: the New York City experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(4):509-518.

Scalea TM, et al. Geriatric blunt multiple trauma: improved survival with invasive monitoring. J Trauma. 1990;30:129-136.

Smith DP, Enderson BL, Maull KI. Trauma in the elderly: determinants of outcome. South Med J. 1990;83:171-177.

Trauma Systems, Pediatric Trauma Centers, and the Neurosurgeon. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 4(3), 2003. (Suppl)

Wright SW, Dronen SC, Combs TJ, Storer D. Aeormedical transport of patients with posttraumatic cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:721-726.