CHAPTER 3 Trauma

Major trauma

Pathophysiology

Several factors must also be considered that can alter the patient’s response to blood loss and must be considered in the resuscitation of these patients. These include the patient’s age, location, type and severity of the injury, the amount of time that has elapsed since the injury, prehospital interventions to address blood loss, and medications taken for chronic conditions, especially anticoagulants and beta-blockers. Since the patient has many other injuries, the classic signs of shock may be altered.

In patients who sustain major trauma, a widespread inflammatory response known as systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) may be triggered by massive tissue injury and the presence of foreign bodies such as road dirt, missiles, and invasive medical devices. Inflammatory mediators activate the coagulation cascade, increased catecholamines stimulate the production and release of white blood cells, and endothelial dysfunction ensues. The hemodynamic response and clinical findings are similar to those with sepsis. (See Chapter 11 for information on SIRS.)

Psychological response

Victims of major trauma sustain life-threatening injuries. The patient often is aware of the situation and fears death. Even after the physical condition stabilizes, the patient may have a prolonged and severe psychological reaction triggered by the trauma called posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Major trauma assessment: primary

Breathing assessment

Major trauma assessment: secondary

Vital signs

• Pulse rate may be elevated if the patient has experienced blood loss or stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) or be decreased in response to elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) from a severe head injury.

• Respiratory rate may also be increased due to SNS stimulation or hypoxia or may be decreased secondary to decreased level of consciousness.

• BP will be elevated with SNS stimulation or increased ICP or decreased due to hemorrhage.

• Temperature may be decreased from exposure to cold environment and development of hemorrhagic shock.

History

Head-to-toe assessment

• ![]() Observe each area for signs of trauma including bruising, abrasions, lacerations, and contusions.

Observe each area for signs of trauma including bruising, abrasions, lacerations, and contusions.

• Palpate each area to feel for crepitus and swelling.

• Auscultate for lung sounds, heart sounds, bowel signs, and bruits.

Labwork

Blood studies can reveal indications of hypoxia and/or continued bleeding and developing shock as well as identify special circumstances such as pregnancy and intoxication.

• Blood typing and screening or cross-matching

• Complete blood counts: hemoglobin (Hgb), increased white blood cell (WBC) count

• Coagulation studies including platelets, prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratio (INR)

• Serial arterial blood gases (ABGs)

• Urine or serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) for pregnancy

| Diagnostic Tests for Major Trauma | ||

|---|---|---|

| Test | Purpose | Abnormal Findings |

| Blood Studies | ||

| Type and screen/type and cross-match | To have type-specific and cross-matched blood available for resuscitation | Inability to cross-match if specimen is collected after multiple units of blood are transfused. |

| Arterial blood gas (ABG) | Assess for adequacy of oxygenation and ventilation and to determine the level of anaerobic metabolism. | pH <7.35 with increased PaCO2 (>45 mm Hg) indicates respiratory acidosis. Serum bicarbonate <22 mEq/L with a pH <7.35 can indicate metabolic acidosis. Decreased PaO2 indicates hypoxemia. Increased PaCO2 indicates inadequate ventilation. Base deficit <−2.0 mEq/L indicates increased oxygen debt. |

| Complete blood count (CBC) Hemoglobin (Hgb) Hematocrit (Hct) |

Assess for blood loss. | Decreased Hgb and Hct indicate blood loss. Often Hgb and Hct are within normal range initially, especially if the patient has not received a significant amount of fluid to replace the blood loss. The Hgb and Hct should be repeated after the patient has a fluid challenge if there is any indication of significant bleeding. |

| Electrolytes Potassium (K+) Glucose Creatinine |

Provide a baseline and assess for possible alterations. | Potassium may be elevated with crush injuries. Glucose is usually elevated after injury. Decreased glucose indicates hypoglycemia and may cause decreased level of consciousness. Elevated creatinine indicates decreased renal functioning, and care should be taken when administering contrast for radiologic studies. |

| Coagulation profile Prothrombin time (PT) with international normalized ratio (INR) Partial thromboplastin time (PTT) Fibrinogen D-dimer |

Assess for causes of bleeding, clotting and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) indicative of abnormal clotting present in shock or ensuing shock. | Decreased PT with low INR promotes clotting; elevation promotes bleeding; elevated fibrinogen and D-dimer reflect abnormal clotting is present. |

| Blood alcohol | To determine the level of alcohol in the patient’s blood | >10 mg/dl indicates the presence of alcohol in the patient’s blood. The higher the level, the more chance the patient has of showing signs of intoxication, but an absolute value will depend on the patient’s tolerance. This may interfere with neurologic assessment. |

| Carbohydrate deficient transferring (CDT) | To identify patients who have had excessive drinking for the past few weeks and may be at risk for alcohol withdrawal | >20 units/L for males and >26 units/L for females indicate excessive drinking. |

| Drug screen | To identify the presence of drugs in the patient”s system | Positive value indicates recent use of the substance. |

| Radiology | ||

| Chest radiograph (CXR) | Assess thoracic cage (for fractures), lungs (pneumothorax, hemothorax); size of mediastinum, size of heart. | Displaced lung margins will be present with pneumothoraces and hemothoraces. Cardiac enlargement may reflect cardiac tamponade. |

| Pelvic radiograph | Assess the integrity of the pelvic ring to indentify fractures and determine stability of the pelvis. | Fracture lines through any of the bones in the pelvis, widening of the symphysis pubis, and widening of the sacroiliac joint(s) |

| Computerized tomography head, neck, chest, abdomen, and/or pelvis | Assess for internal injuries. | Any findings of skeletal fractures, misalignment, organ damage, or abnormal collections of blood indicates injury to the organ/tissue involved. |

| Ultrasound: FAST Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma |

Assess for fluid around the heart, liver, spleen and bladder. | Abnormal collection of fluid |

| Invasive Studies | ||

| Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) | Assess for blood or in the peritoneal cavity or abnormal substrates in the peritoneal lavage fluid. | The presence of red or white blood cells, bile, food fibers, amylase, or feces in the lavage fluid suggests injury to the abdominal organs. Lavage fluid coming from the Foley catheter indicates bladder rupture. Lavage fluid coming from the chest tube, if present, indicates diaphragm rupture. |

Collaborative management

Care priorities

3. Manage hemorrhage and hypovolemia:

Stopping blood loss and restoring adequate circulating blood volume are imperative. Lack of resuscitation will lead to increasing oxygen debt and eventually to MODS and death. The goal of resuscitation in any trauma patient should be to restore adequate tissue perfusion. Two or more large-bore (XXgw:math1XX^ZZgw:math1ZZ16-gauge) short catheters should be placed to maximize delivery of fluids and blood. Use of intravenous (IV) tubing with an exceptionally large internal diameter (trauma tubing), absence of stopcocks, and use of external pressure are techniques used to promote rapid fluid volume therapy when indicated. In some cases the patient may require large central venous access, such as an 8.5 Fr introducer. When rapid infusion of large amounts of fluid is required, all fluid should be warmed to body temperature to prevent hypothermia. Rapid warmer/infuser devices are available to facilitate rapid administration of blood products. Fluid resuscitation should be used more judiciously in pediatric and older patients, as well as patients with significant craniocerebral trauma, who have precise fluid requirements (see Traumatic Brain Injury, p. 341).

• Crystalloids: Initial fluid used for resuscitation should be an isotonic electrolyte solution such as 0.9% normal saline (NS), or lactated Ringer’s (LR). Other balanced electrolyte solutions, such as Normosol-R pH 7.4 (Hospira) or Plasmalyte-A 7.4 (Baxter) may be used after initial fluid resuscitation has been completed.

• Rapid bolus: From 1 to 2 L of rapid IV fluid infusion for adults and 20 ml/kg for pediatric patients should be initiated in the prehospital setting. If the patient continues to show signs of shock after the bolus is complete, blood transfusions should be considered.

• Packed red blood cells (PRBCs): Typed and cross-matched blood is ideal, but in the immediate resuscitation period, if cross-matched blood is not available, type O blood may be used. Once the patient has been typed, type-specific blood can be used. Those patients requiring continuous blood transfusions need reassessment to identify the source of bleeding and definitive treatment to stop ongoing blood loss. A massive transfusion protocol may also need to be initiated.

• Massive transfusion is defined as replacement of one half of the patient’s blood volume at one time or complete replacement of the patient’s blood volume over 24 hours. A massive transfusion protocol ensures the patient receives plasma, platelets, and cryoprecipitate in addition to the packed red blood cells to prevent the complications related to coagulopathy. Another concern with massive transfusion is hypocalcemia caused by calcium binding with citrate in stored PRBCs, resulting in depressed myocardial contractility, particularly in hypothermic patients or in those with impaired liver function. One ampule of 10% calcium chloride should be considered for administration after every 4 units of PRBCs.

• Autotransfusion: Shed blood from the patient can be collected, filtered, and reinfused. Shed blood is captured from chest tube drainage or the operative field and reinfused immediately. Various techniques are used to capture and reinfuse the blood. Advantages of autotransfusion include reduced risk of disease transmission, absence of incompatibility problems, and availability. Disadvantages include risk of blood contamination and presence of naturally occurring factors that promote anticoagulation.

• Colloids: Resuscitation with colloids has not been shown to reduce mortality and is not used in the initial resuscitation of trauma patients.

• Recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa): The standard use of rFVIIa in the resuscitation of trauma patients is still controversial. Some studies have shown a decrease in the number of units of PRBCs required for patients in hemorrhagic shock but have not shown a decrease in mortality. More studies are needed to determine the appropriate indications, contraindications, dosage, and timing of rFVIIa administration in trauma patients experiencing hemorrhagic shock.

An indwelling catheter is inserted to obtain a specimen for urinalysis and to monitor hourly urine output. See Renal and Lower Urinary Tract Trauma, p. 317, for precautions.

8. Control pain and anxiety with analgesics and anxiolytics:

Relief of pain and anxiety are accomplished using IV opiates and anxiolytics. All IV agents should be carefully titrated to desired effect, while avoiding respiratory depression, masking injury, or disguising changes in physiologic parameters. Use of the World Health Organization (WHO) ladder for pain management and a pain-rating scale are essential for the trauma population.

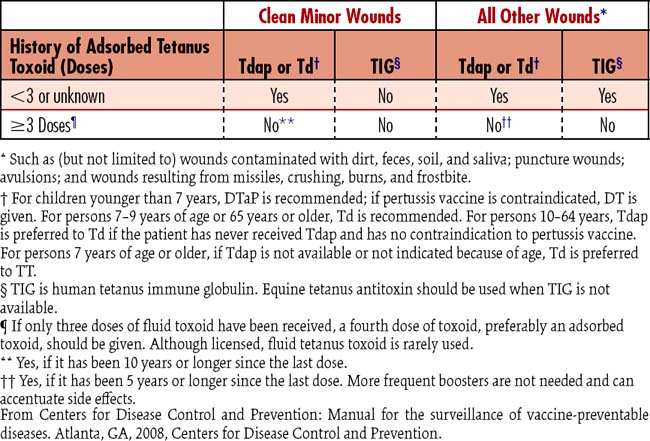

9. Provide tetanus prophylaxis:

Tetanus immunoglobulin and tetanus-toxoid are considered on the basis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations (Table 3-1).

10. Initiate nutritional support therapy:

![]() Infection and sepsis contribute to the negative nitrogen state and increased metabolic needs. Prompt initiation of nutrition therapy is essential for rapid healing and prevention of complications. Parenteral nutrition or postpyloric (jejunal) feedings may be used if postoperative ileus or injury to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is present. For more information, see Nutritional Support, p. 117.

Infection and sepsis contribute to the negative nitrogen state and increased metabolic needs. Prompt initiation of nutrition therapy is essential for rapid healing and prevention of complications. Parenteral nutrition or postpyloric (jejunal) feedings may be used if postoperative ileus or injury to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is present. For more information, see Nutritional Support, p. 117.

11. Facilitate evaluation for surgery:

CARE PLANS: MAJOR TRAUMA

Ineffective tissue perfusion, cardiopulmonary

related to significant blood loss/volume

1. Monitor for sudden blood loss or persistent bleeding.

2. Prevent blood volume loss (e.g., apply pressure to site of bleeding).

3. Monitor for fall in systolic BP to less than 90 mm Hg or a fall of 30 mm Hg in hypertensive patients.

4. Monitor for signs/symptoms of hypovolemic shock (e.g., increased thirst, increased HR, increased systemic vascular resistance (SVR), decreased urinary output [urine output], decreased bowel sounds, decreased peripheral perfusion, altered mental status, or altered respirations).

5. Position the patient for optimal perfusion.

6. Insert and maintain large-bore IV access.

7. Administer warmed IV fluids, such as isotonic crystalloids, as indicated.

8. Administer blood products (e.g., PRBCs, platelets, plasma, and cryoprecipitate) as appropriate.

9. Administer oxygen and/or mechanical ventilation, as appropriate.

10. Draw arterial blood gases and monitor tissue oxygenation.

11. Monitor Hgb/hematocrit (Hct) level.

12. Monitor coagulation studies, including INR, PT, PTT, fibrinogen, fibrin degradation/split products, and platelets.

13. Monitor lab studies (e.g., serum lactate, acid-base balance, metabolic profiles, and electrolytes).

14. Monitor fluid status, including intake and output, as appropriate.

15. Monitor for clinical signs and symptoms of overhydration/fluid excess.

1. Monitor BP, pulse, temperature, and respiratory status, as appropriate.

2. Note trends and wide fluctuations in BP.

3. Auscultate BPs in both arms and compare, as appropriate.

4. Initiate and maintain a continuous temperature monitoring device, as appropriate.

5. Monitor for and report signs and symptoms of hypothermia and hyperthermia.

1. Examine the pH level in conjunction with the PaCO2 and HCO3 levels to determine whether the acidosis/alkalosis is compensated or uncompensated.

2. Monitor for an increase in the anion gap (greater than 14 mEq/L), signaling an increased production or decreased excretion of acid products.

3. Monitor base excess/base deficit levels.

4. Monitor arterial lactate levels.

5. Monitor for elevated chloride levels with large volumes of NS.

related to airway obstruction, inadequate oxygenation

![]() Respiratory Status: Gas Exchange; Respiratory Status: Ventilation

Respiratory Status: Gas Exchange; Respiratory Status: Ventilation

1. Assess for patent airway; if snoring, crowing, or strained respirations are present, indicative of partial or full airway obstruction, open airway using chin-lift or jaw-thrust and maintain cervical spine alignment.

2. Insert oral or nasopharyngeal airway if patient cannot maintain patent airway; if severely distressed, patient may require endotracheal intubation.

3. When spine is cleared, position patient to alleviate dyspnea and ensure maximal ventilation, generally in a sitting inclined position unless severe hypotension is present.

4. Clear secretions from airway by having patient cough vigorously, or provide nasotracheal, oropharyngeal, or endotracheal tube suctioning as needed.

5. Have patient breathe slowly or manually ventilate with bag-valve-mask device slowly and deeply between coughing or suctioning attempts.

6. Assist with use of incentive spirometer as appropriate.

7. Turn patient every 2 hours if immobile. Encourage patient to turn self, or get out of bed as much as tolerated if patient is able.

8. Provide chest physical therapy as appropriate, if other methods of secretion removal are ineffective.

1. Provide humidity in oxygen.

2. Administer supplemental oxygen using liter flow and device as ordered.

3. Restrict patient and visitors from smoking while oxygen is in use.

4. Document pulse oximetry with oxygen liter flow in place at time of reading as ordered. Oxygen is a drug; the dose of the drug must be associated with the oxygen saturation reading or the reading is meaningless.

5. Obtain arterial blood gases if patient experiences behavioral changes or respiratory distress to check for hypoxemia or hypercapnia.

6. Monitor for changes in chest radiograph and breath sounds indicative of oxygen toxicity and absorption atelectasis in patients receiving higher concentrations of oxygen (FIO2 greater than 45%) for longer than 24 hours. The higher the oxygen concentration, the greater is the chance of toxicity.

7. Monitor for skin breakdown where oxygen devices are in contact with skin, such as nares and around edges of mask devices.

8. Provide oxygen therapy during transportation and when patient gets out of bed.

1. Monitor rate, rhythm, and depth of respirations.

2. Note chest movement for symmetry of chest expansion and signs of increased work of breathing such as use of accessory muscles or retraction of intercostal or supraclavicular muscles.

3. Ensure airway is not obstructed by tongue (snoring or choking-type respirations) and monitor breathing patterns. New patterns that impair ventilation should be managed as appropriate for setting.

4. Note that trachea remains midline, as deviation may indicate patient has a tension pneumothorax.

5. Auscultate breath sounds following administration of respiratory medications to assess for improvement.

6. Note changes in oxygen saturation (SaO2), pulse oximetry (SpO2), end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2), and ABGs as appropriate.

7. Monitor for dyspnea and note causative activities/events.

8. If increased restlessness or unusual somnolence occurs, evaluate patient for hypoxemia and hypercapnia as appropriate.

9. Monitor chest x-ray reports as new films become available.

![]() Comfort Status: Physical, Pain Level

Comfort Status: Physical, Pain Level

1. Assess and document the location and intensity of the pain. Devise a pain scale with patient, rating discomfort from 0 (no pain) to 10 or any system that assists in objectively reporting pain level. If intubated, use a physiologic scale such as adult nonverbal pain scale or the FLACC scale.

2. Determine the needed frequency of making an assessment of patient comfort and implement monitoring plan.

3. Provide the patient with optimal pain relief with prescribed analgesics.

4. Ensure pretreatment analgesia and/or nonpharmacologic strategies prior to painful procedures.

5. Evaluate the effectiveness of the pain control measures used through ongoing assessment of the pain experience.

related to altered temperature regulation

Patient will maintain a normal body temperature above 36°C (96.8°F).

1. Cover with warmed blankets, as appropriate.

2. Administer warmed (37° to 40°C) IV fluids, as appropriate.

3. Administer heated oxygen, as appropriate.

4. Infuse all whole blood and PRBCs through a warmer.

5. Institute active core rewarming techniques (e.g., colonic lavage, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and extracorporeal blood rewarming), as appropriate.

![]() related to inadequate coping ability due to major physical and emotional stress

related to inadequate coping ability due to major physical and emotional stress

1. Explain all procedures, including sensations likely to be experienced during the procedure.

2. Provide factual information concerning diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

3. Encourage family to stay with patient, as appropriate.

4. Create an atmosphere to facilitate trust.

5. Control stimuli as appropriate, for the patient needs.

6. Determine the patient’s decision-making ability.

7. Administer medications to reduce anxiety, as appropriate.

1. Provide an atmosphere of acceptance.

2. Provide the patient with realistic choices about certain aspects of care.

3. Acknowledge the patient’s spiritual/cultural background.

4. Encourage the use of spiritual resources, if desired.

5. Encourage verbalization of feelings, perceptions, and fears.

6. Assist the patient to identify available social supports.

Additional nursing diagnoses

Also see nursing diagnoses and interventions as appropriate in Nutritional Support (p. 117), Mechanical Ventilation (p. 99), Hemodynamic Monitoring (p. 75), Prolonged Immobility (p. 149), and Emotional and Spiritual Support of the Patient and Significant Others (p. 200).

Abdominal trauma

Pathophysiology

Blunt trauma

There are three mechanisms of action with blunt trauma.

1. Rapid deceleration: On impact, the different organs that reside inside abdominal cavity move at different speeds depending on their density. This creates what is known as shear force, that is, two different directions applied to the organ, usually at the point of attachment, causing injury to other organs such as the aorta.

2. Crush of contents between the walls: Solid viscera are exceptionally affected when the compression occurs from the anterior abdominal wall and the spine or posterior cage.

3. External compression force: The force of external traumatic impact may increase the organ and abdominal pressures to such a degree that the hollow organs rupture.

Mechanisms of action with penetrating injury

• Diaphragm: Commonly injured at the left posterior portion after blunt trauma, the tear is best visualized by chest radiograph, which reveals an elevation of the left hemidiaphragm and air under the diaphragm.

• Spleen: The organ most frequently injured after blunt trauma, massive hemorrhage from splenic injury is common. Damage to the spleen may occur with the most trivial of injuries, so index of suspicion should be high. Splenic injury is often associated with hepatic or pancreatic injury due to close proximity of these organs. Splenectomy is the treatment of choice for major spleen injuries. Minor splenic injuries may be managed with direct suture techniques

• Liver: Most frequently involved in penetrating trauma (80%) because of its large size and location, the liver is less often affected by blunt injury (20%). Control of bleeding and bile drainage is the priority with hepatic injury. Mortality from liver injuries is about 10%. In most patients, bleeding from a liver injury can be controlled, such as with perihepatic packing. About 5% of injuries require packing for bleeds. Major arterial bleeding from the liver parenchyma will require further attention. Biliary tree injuries may require surgical repair and should be suspected with liver injury. The patient may be asymptomatic or have mild to moderate abdominal discomfort with biliary tree injury.

• Retroperitoneal vessels: Tears in retroperitoneal vessels associated with pelvic fractures or damage to retroperitoneal organs (pancreas, duodenum, and kidney) can cause bleeding into the retroperitoneum.

• Although the retroperitoneal space can accommodate up to 4 L of blood, detection of retroperitoneal hematomas is difficult and sophisticated diagnostic techniques may be required.

• Colon: Injury is most frequently caused by penetrating forces, although lap belts, direct blows, and other blunt forces cause a small percentage of colonic injuries. Because of the high bacterial content, infection is even more a concern than it is with small bowel injury. Most patients with significant colon injuries require a temporary colostomy.

• Undetected mesenteric damage: May cause compromised blood flow, with eventual bowel infarction. Perforations or contusions result in release of bacteria and intestinal contents into the abdominal cavity, causing serious infection.

Assessment: abdominal trauma

History and risk factors

First and foremost, it is essential to establish issues involved with the injury event (Box 3-1). These details regarding circumstances of the accident and mechanism of injury are invaluable in detecting the presence of specific injuries. Second, allergies, medications, and last meal eaten will play an important role in the maintenance of good resuscitation. Other information, previous abdominal surgeries, and use of safety restraints (if appropriate) should be noted. Hollow viscous injury is often missed but should always be suspected with a visible contusion on the abdomen. Medical information including current medications and last tetanus-toxoid immunization should be obtained. The history is sometimes difficult to obtain because of alcohol or drug intoxication, head injury, breathing difficulties, or impaired cerebral perfusion. Family members and emergency personnel may be valuable sources of information.

Vital signs

• ![]() Hypotension: Presence of hypotension is a sign of impending doom, but the absence of hypotension does not always accurately reflect an absence of hemorrhage. After an injury, a profound neuroendocrine response ensues to activate the beta receptors (sinus node and ventricular contractile tissue), the alpha receptors (smooth muscle in the arteries), and the renal tubules (promoting preservation of fluid), resulting in significant tachycardia, profound vasoconstriction, and progressive oliguria. These responses may mask the severity of hemorrhage. Patients on alpha or beta antagonists or those with acute spinal cord injuries (above C5) will not manifest these responses and therefore will have few compensatory mechanisms.

Hypotension: Presence of hypotension is a sign of impending doom, but the absence of hypotension does not always accurately reflect an absence of hemorrhage. After an injury, a profound neuroendocrine response ensues to activate the beta receptors (sinus node and ventricular contractile tissue), the alpha receptors (smooth muscle in the arteries), and the renal tubules (promoting preservation of fluid), resulting in significant tachycardia, profound vasoconstriction, and progressive oliguria. These responses may mask the severity of hemorrhage. Patients on alpha or beta antagonists or those with acute spinal cord injuries (above C5) will not manifest these responses and therefore will have few compensatory mechanisms.

• Pulse pressure: This measure may be effectively used to determine the amount of volume in the arteries (systolic minus diastolic BP, normal greater than 40 mm Hg). Pulse pressure generally correlates with the volume ejected by the left ventricle and therefore is a valuable tool for indication of volume in the vascular bed. Presence of pulsus paradoxus (Box 3-2) may be visualized with either the invasive arterial pressure trace or the plethysmograph of the pulse oximeter and is an invaluable tool in evaluating arterial volume.

Box 3-2 MEASURING PARADOXICAL PULSE

• After placing BP cuff on patient, inflate it above the known systolic BP. Instruct patient to breathe normally.

• While slowly deflating the cuff, auscultate BP.

• Listen for the first Korotkoff sound, which will occur during expiration with cardiac tamponade.

• Note the manometer reading when the first sound occurs, and continue to deflate the cuff slowly until Korotkoff sounds are audible throughout inspiration and expiration.

• Record the difference in millimeters of mercury between the first and second sounds. This is the pulsus paradoxus.

Observation and subjective/objective symptoms

• Inspection of all surfaces of trunk, head, neck, and extremities, including anterior lateral and posterior exposure, with notation of all penetrating wounds, contusions, tenderness, ecchymosis, or other marks and indicators. Multiple wounds may represent entrance or exit wounds but do not eliminate the possibility of objects that may remain internally.

• Kehr sign (left shoulder pain caused by splenic bleeding) also may be noted, especially when the patient is recumbent.

• Nausea and vomiting may occur, and the conscious patient who has sustained blood loss often complains of thirst—an early sign of hemorrhagic shock.

• Preoperative pain is anticipated and is a vital diagnostic aid. The nature of postoperative pain also can be important. Incisional and some visceral pain can be anticipated, but intense or prolonged pain, especially when accompanied by other peritoneal signs, can signal bleeding, bowel infarction, infection, or other complications.

Inspection

• Abrasions and ecchymoses may indicate underlying injury. The absence of ecchymosis does not exclude major abdominal trauma and massive internal bleeding. In the event of gunshot wounds, entrance and exit (if present) wounds should be identified.

• Ecchymosis over the left upper quadrant (LUQ) suggests splenic rupture, and erythema and ecchymosis across the lower portion of the abdomen suggest intestinal injury caused by lap belts.

• Grey-Turner sign, a bluish discoloration of the flank, may indicate retroperitoneal bleeding from the pancreas, duodenum, vena cava, aorta, or kidneys.

• Cullen sign, a bluish discoloration around the umbilicus, may be present with intraperitoneal bleeding from the liver or spleen. Ecchymosis may take hours to days to develop, depending on the rate of blood loss.

Auscultation

• Bowel sounds: These are likely to be decreased or absent with abdominal organ injury or intraperitoneal bleeding. The presence of bowel sounds, however, does not exclude significant abdominal injury. Immediately after injury, bowel sounds may be present, even with major organ injury. Bowel sounds should be auscultated in each quadrant every 1 to 2 hours in patients with suspected abdominal injury. Absence of bowel sounds is expected immediately after surgery. Failure to auscultate bowel sounds within 24 to 48 hours after surgery suggests ileus, possibly caused by continued bleeding, peritonitis, or bowel infarction.

Palpation

• Tenderness to light palpation suggests pain from superficial or abdominal wall lesions, such as that occurring with seatbelt contusions.

• Deep palpation may reveal a mass, which may indicate a hematoma. Internal injury with bleeding or release of GI contents into the peritoneum results in peritoneal irritation and certain assessment findings. Box 3-3 describes signs and symptoms that suggest peritoneal irritation.

• Subcutaneous emphysema of the abdominal wall is usually caused by thoracic injury but also may be produced by bowel rupture.

• Measurements of abdominal girth may be helpful in identifying increases in girth attributable to gas, blood, or fluid. Visual evaluation of abdominal distention is a late and unreliable sign of bleeding.

• Peritoneal signs (pain, guarding, rebound tenderness) or abdominal distention in an unconscious patient requires immediate evaluation in either case.

Percussion

• Unusually large areas of dullness may be percussed over ruptured blood-filled organs. For example, a fixed area of dullness in the LUQ suggests a ruptured spleen. An absence (or decrease in the size) of liver dullness may be caused by free air below the diaphragm, a consequence of hollow viscous perforation, or, in unusual cases, displacement of the liver through a ruptured diaphragm.

• The presence of tympany suggests gas; dullness suggests that the enlargement is caused by blood or fluid.

HIGH ALERT!

Massive intestinal edema is common following laparotomy and prolonged shock. Inflammatory response, neuroendocrine stimulation, aggressive crystalloid resuscitation, bowel handling, intra-abdominal packing, and retroperitoneal hematomas may cause a delay in abdominal closure. If the abdomen is closed, the intra-abdominal volume may compress arteries, capillaries, the bladder, and the ureters. This compartment hypertension (abdominal compartment syndrome) may cause a significant hypotension, oliguria, and base deficit that will be difficult to combat. (See Abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome, p. 861).

| Diagnostic Evaluation of Abdominal Trauma | ||

|---|---|---|

| Test | Purpose | Abnormal Findings |

| FAST: focused assessment with sonography for trauma | Rapid, portable, noninvasive method to detect hemoperitoneum Uses four views to evaluate |

Based on the assumption that all clinically significant abdominal injuries are associated with hemoperitoneum. If positive for blood, may require CT. If negative, but suspicious, proceed to DPL. |

| CT scan | Used to evaluate integrity of cavities and organs | Wound tract outlined by hemorrhage, air, bullet or bone fragments that clearly extend into the peritoneal cavity; the presence of intraperitoneal free air, free fluid, or bullet fragments; and obvious intraperitoneal organ injury |

| Rectal examination | Evaluate for bony penetration | Blood in the stool (gross or occult) and/or the presence of a high riding prostate (indicates genitourinary or bowel injury) |

| Chest radiograph (CXR) | Assess size and integrity of heart, thoracic cage and lungs; rules out chest cavity penetration | Hemothoraces or pneumothoraces; air under diaphragm indicates peritoneal penetration. |

| Blood Studies | ||

| Complete blood count (CBC) Hemoglobin (Hgb) Hematocrit (Hct) RBC count (RBCs) WBC count (WBCs) |

Assess for occult bleeding or effects of gross bleeding | Decreased Hgb or Hct reflects blood loss, may be false negative when patient has lost significant volume. Repeat after 2 L of isotonic fluid resuscitation. |

| Electrolytes Potassium (K+) Magnesium (Mg2+) Calcium (Ca2+) Sodium (Na+) |

Assess for possible causes of dysrhythmias and/or heart failure | Decrease in K+, Mg2+, or Ca2+ may cause dysrhythmias. Elevation of Na+ may indicate dehydration. |

| Coagulation profile Prothrombin time (PT) with international normalized ratio (INR) Partial thromboplastin time (PTT) Fibrinogen D-dimer |

Assess for causes of bleeding, clotting, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) indicative of abnormal clotting present in shock or ensuing shock | Decreased PT with low INR promotes clotting; elevation promotes bleeding; elevated fibrinogen and D-dimer reflects abnormal clotting is present. |

Collaborative management

The initial focus should be stabilization and supporting hemodynamics, but the highest priority is to diagnose and repair causes of hemorrhage. Timely provision of needed surgery, preferably in a trauma center, is the critical factor impacting survival. Prolonged hypovolemia and shock result in organ ischemia and ultimately failure (see Major Trauma [p. 235], Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome [p. 365], Cardiogenic Shock [p. 472], Acute Renal Failure [p. 584], Hepatic Failure [p. 785]).

Care priorities

3. Manage hypovolemia and anemia:

Because massive blood loss is associated with most abdominal injuries, immediate volume resuscitation is critical. Initially, LR or a similar balanced salt solution is given. Colloid solutions may be helpful in the postoperative period if there are low filling pressures and evidence of decreased plasma oncotic pressure. Typed and cross-matched fresh blood is the optimal fluid for replacement of large blood losses. However, since fresh whole blood is rarely available, a combination of packed cells and fresh frozen plasma often is used. Overaggressive use of colloids and PRBCs may increase third spacing and SIRS. (See Major Trauma, p. 235, for more information.)

• Indication for immediate blood transfusion: Ongoing blood loss indicates hemodynamic instability despite the administration of 2 L of fluid to adult patients.

• Acidosis: Hemorrhagic shock reduces perfusion, resulting in hypoxemia, anaerobic metabolism, and lactic acidosis. The compensatory vasoconstrictive response shunts blood to the heart, lungs, and brain from the skin, muscles, and abdominal organs. Base deficit or lactate levels should be used to guide fluid resuscitation, ventilation, and BP support.

• Coagulopathy: Hypothermia, acidosis, and massive blood transfusion all lead to coagulopathy. The top priority is to stop the bleeding. Coagulopathy is treated by the administration of fresh frozen plasma, factor VII, cryoprecipitate, and platelets and correcting the hypothermia and acidosis. If bleeding persists, consider vasopressin infusion, which causes vasoconstriction and calcium chloride.

4. Consider surgery for penetrating abdominal injuries:

• Indication for emergency laparotomy:

• Removing penetrating objects can result in additional injury; thus attempts at removal should be made only under controlled situations with a surgeon and operating room immediately available.

• If evisceration occurs initially or develops later, do not reinsert tissue or organs. Place a saline-soaked gauze over the evisceration, and cover with a sterile towel until the evisceration can be evaluated by the surgeon.

• The issue of mandatory surgical exploration versus observation and selective surgery, especially with stab wounds, remains controversial. There is a trend toward observation of patients without obvious injury or peritoneal signs.

• Indications for laparotomy include one or more of the following: (1) penetrating injury suspected of invading the peritoneum (e.g., abdominal gunshot wound or abdominal stab wound with evisceration, hypotension, or peritonitis); (2) positive peritoneal signs (e.g., tenderness, rebound tenderness, involuntary guarding); (3) shock; (4) GI hemorrhage; (5) free air in the peritoneal cavity as seen on x-ray film; (6) evisceration; (7) massive hematuria; and (8) positive findings on DPL.

5. Consider an appropriate surgical intervention based on type of injury:

• Blunt, nonpenetrating abdominal injuries: Physical examination is important in determining the necessity for surgery in alert, cooperative, nonintoxicated patients. Additional diagnostic tests such as abdominal ultrasound, DPL, or CT are necessary to evaluate the need for surgery in the patient who is intoxicated or unconscious or who has sustained head or spinal cord trauma.

![]() • Need for immediate surgery vs. triad of failure: Once in the operating room, it may become apparent that the patient cannot survive a long procedure, or that the triad of failure (acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy) may cause death. At this point the surgeon may do limited repair and packing, choosing to delay major surgical repair.

• Need for immediate surgery vs. triad of failure: Once in the operating room, it may become apparent that the patient cannot survive a long procedure, or that the triad of failure (acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy) may cause death. At this point the surgeon may do limited repair and packing, choosing to delay major surgical repair.

6. Considerations regarding closure of the abdominal surgical incision:

1. Silo bag closure: A 3-L sterile plastic irrigation bag is emptied and cut to lie flat. The edges are trimmed and sutured to the skin.

2. Vacuum pack: A 3-L sterile plastic irrigation bag is emptied and cut to lie flat, then placed into the abdomen, and the edges are placed under the sheath. Two suction drains are placed on top of the bag, and a large adherent steridrape is then placed over the whole abdomen. The catheters are placed to suction, providing continuous drainage.

3. Vacuum-assisted closure: This consists of a sterile sponge dressing with an adherent dressing and a continuous negative pressure; it promotes closure, blood flow, and collagen formation.

7. Provide nutritional support:

Patients with abdominal trauma have complex nutritional needs because of the hypermetabolic state associated with major trauma and traumatic or surgical disruption of normal GI function. Often infection and sepsis contribute to a negative nitrogen state and increased metabolic needs. Prompt initiation of parenteral or postpyloric feedings, as appropriate, in patients unable to accept conventional enteric feedings and the administration of supplemental calories, proteins, vitamins, and minerals are essential for healing. For additional information, see Nutritional Support, p. 117.

9. Manage pain using analgesics:

CARE PLANS: ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

related to active loss of blood volumes or secondary to management of fluids

![]() Fluid Balance; Electrolyte and Acid-Base Balance

Fluid Balance; Electrolyte and Acid-Base Balance

1. Monitor BP every 15 minutes, or more frequently in the presence of obvious bleeding or unstable vital signs. Be alert to changes in MAP of greater than 10 mm Hg.

2. Monitor HR, ECG, and cardiovascular status every 15 minutes until volume is restored and vital signs are stable. Check ECG to note HR elevations and myocardial ischemic changes (i.e, ventricular dysrhythmias, ST-segment changes), which can occur because of dilutional anemia in susceptible individuals.

3. In the patient with evidence of volume depletion or active blood loss, administer pressurized fluids rapidly through several large-caliber (16-gauge or larger) catheters. Use short, large-bore IV tubing (trauma tubing) to maximize flow rate. Avoid use of stopcocks, because they slow the infusion rate.

4. Fluids should be warmed to prevent hypothermia.

5. Measure central pressures and thermodilution CO every 1 to 2 hours or more frequently if blood loss is ongoing. Calculate SVR and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) every 4 to 8 hours or more often in unstable patients. Be alert to low or decreasing CVP and PAWP.

HIGH ALERT!

![]() An elevated HR, along with decreased PAWP, decreased CO/CI, and increased SVR, suggests hypovolemia (see Table 5-10 for hemodynamic profile of hypovolemic shock). Anticipate slightly elevated HR and CO caused by hyperdynamic cardiovascular state in some patients who have undergone volume resuscitation, particularly during the preoperative phase. Also anticipate mild to moderate pulmonary hypertension, especially in patients with concurrent thoracic injury, such as pulmonary contusion, smoke inhalation, or early acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ARDS is a concern in patients who have sustained major abdominal injury, inasmuch as there are many potential sources of infection and sepsis that make the development of ARDS more likely (see Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, p. 365).

An elevated HR, along with decreased PAWP, decreased CO/CI, and increased SVR, suggests hypovolemia (see Table 5-10 for hemodynamic profile of hypovolemic shock). Anticipate slightly elevated HR and CO caused by hyperdynamic cardiovascular state in some patients who have undergone volume resuscitation, particularly during the preoperative phase. Also anticipate mild to moderate pulmonary hypertension, especially in patients with concurrent thoracic injury, such as pulmonary contusion, smoke inhalation, or early acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ARDS is a concern in patients who have sustained major abdominal injury, inasmuch as there are many potential sources of infection and sepsis that make the development of ARDS more likely (see Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, p. 365).

6. Measure urinary output every 1 to 2 hours. Be alert to output less than 0.5 ml/kg/hr for 2 consecutive hours. Low urine output usually reflects inadequate intravascular volume in the patient with abdominal trauma.

7. Monitor for physical indicators of arterial hypovolemia: (1) cool extremities, (2) capillary refill greater than 2 seconds, (3) absent or decreased amplitude of distal pulses, (4) elevated serum lactate, and (5) base deficit.

8. Estimate ongoing blood loss. Measure all bloody drainage from tubes or catheters, noting drainage color (e.g., coffee grounds, burgundy, bright red [Table 3-2]). Note the frequency of dressing changes as a result of saturation with blood to estimate amount of blood loss by way of the wound site.

| Source | Composition and Usual Character |

| Mouth and oropharynx | Saliva; thin, clear, watery; pH 7 |

| Stomach | Hydrochloric acid, gastrin, pepsin, mucus; thin, brown to green, acidic |

| Pancreas | Enzymes and bicarbonate; thin, water, yellowish brown; alkaline |

| Biliary tract | Bile, including bile salts and electrolytes; bright yellow to brownish green |

| Duodenum | Digestive enzymes, mucus, products of digestion; thin, bright yellow to light brown, may be green, alkaline |

| Jejunum | Enzymes, mucus, products of digestion; brown, watery with particles |

| Ileum | Enzymes, mucus, digestive products, greater amounts of bacteria; brown, liquid, feculent |

| Colon | Digestive products, mucus, large amounts of bacteria; brown to dark brown, semiformed to firm stool |

| Postoperative (gastrointestinal surgery) | Initially, drainage expected to contain small amounts of fresh blood appearing bright to dark; later, drainage mixed with old blood appearing dark brown (“coffee grounds”); and then approaches normal composition |

| Infection present | Drainage cloudy, may be thicker than usual; strong or unusual odor, drain site often erythematous and warm |

It is important to know the normal in order to recognize the abnormal.

![]() Electrolyte Management; Fluid Monitoring; Hypovolemia Management

Electrolyte Management; Fluid Monitoring; Hypovolemia Management

related to physical injury secondary to trauma or surgical intervention

1. Medicate appropriately for pain relief. It is important to note that opiate analgesics can decrease GI motility, causing nausea, vomiting, and delay of bowel activity. These factors are especially significant if the patient has had a recent laparotomy.

2. Provide comfort measures, maintain proper positioning of affected extremities while turning patient and supporting incisional areas.

3. Explain procedures to patient and include education regarding pain relief measures.

1. Note color, character, and odor of all drainage from any surgical site, orifice, drain, or site of invasive catheters.

2. Report the presence of foul-smelling or abnormal drainage. See Table 3-2 for a description of the usual character of GI drainage.

3. Monitor temperature, hemodynamics, and vital signs closely.

4. For more interventions, see this diagnosis in Major Trauma, p. 235.

Ineffective tissue perfusion: gastrointestinal

1. Auscultate for bowel sounds hourly during the acute phase of abdominal trauma and every 4 to 8 hours during the recovery phase. Report prolonged or sudden absence of bowel sounds during the postoperative period, because these signs may signal bowel ischemia or mesenteric infarction.

2. Evaluate patient for peritoneal signs (see Box 3-3), which may occur initially as a result of injury or may not develop until days or weeks later, if complications caused by slow bleeding or other mechanisms occur.

3. Ensure adequate intravascular volume (see Deficient Fluid Volume, p. 253).

4. Evaluate laboratory data for evidence of bleeding (e.g., serial Hct) or organ ischemia (e.g., AST, ALT, lactic dehydrogenase [LDH]). Desired values are as follows: Hct greater than 28% to 30%, AST 5 to 40 IU/L, ALT 5 to 35 IU/L, and LDH 90 to 200 U/L.

5. Document amount and character of GI secretions, drainage, and excretions.

6. Assess and report any indicators of infection or bowel obstruction (e.g., fever, severe or unusual abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, unusual drainage from wounds or incisions, change in bowel habits).

![]() Tissue Integrity: Skin and Mucous Membranes

Tissue Integrity: Skin and Mucous Membranes

1. Protect the skin surrounding tubes, drains, or fistulas, keeping the areas clean and free from drainage. Gastric and intestinal secretions and drainage are highly irritating and can lead to skin excoriation. If necessary, apply ointments, skin barriers, or drainage pouches to protect the surrounding skin. If available, consult ostomy nurse for complex or involved cases.

2. For other interventions, see this diagnosis in Major Trauma, p. 235.

Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements

![]() Nutritional Status: Food and Fluid Intake; Nutritional Status

Nutritional Status: Food and Fluid Intake; Nutritional Status

1. Collaborate with physician, dietician, and pharmacist to estimate patient’s metabolic needs on the basis of type of injury, activity level, and nutritional status before injury.

2. Consider patient’s specific injuries when planning nutrition. For example, expect patients with hepatic or pancreatic injury to have difficulty with blood sugar regulation.

3. Patients with trauma to the upper GI tract may be fed enterally, but feeding tube must be placed distal to the injury. Disruption of the GI tract may require a feeding gastrostomy or jejunostomy. Patients with major hepatic trauma may have difficulty with protein tolerance.

4. Ensure patency of gastric or intestinal tubes to maintain decompression and encourage healing and return of bowel function. Avoid occlusion of the vent side of sump suction tubes, because this may result in vacuum occlusion of the tube.

• For additional information, see Nutritional Support (p. 117) and Major Trauma (p. 235).

![]() Electrolyte Management; Feeding; Nutrition Therapy; Tube Feeding

Electrolyte Management; Feeding; Nutrition Therapy; Tube Feeding

1. Evaluate the patient’s reaction to the stoma or missing/mutilated body part by observing and noting evidence of body image disturbance (see Box 2-4).

2. Anticipate feelings of shock and disbelief initially. Be aware that trauma patients usually do not receive the emotional preparation for ostomy, amputation, and other disfiguring surgery that the patient undergoing elective surgery receives.

3. Anticipate and acknowledge normalcy of feelings of rejection and isolation (and uncleanliness in the case of fecal diversion).

4. Offer patient opportunity to view stoma/altered body part. Use mirrors if necessary.

5. Encourage patient and significant others to verbalize feelings regarding altered/missing body part.

6. Offer patient the opportunity to participate in care of ostomy, wound, or incision.

7. Confer with surgeon regarding advisability of a visit by an ostomate or a patient with similar alteration in body part.

8. Be aware that most colostomies are temporary in persons with colonic trauma. This fact can be reassuring to the patient, but it is important to verify the type of colostomy with the surgeon before explaining this to the patient.

Additional nursing diagnoses

Also see Major Trauma for Hypothermia (p. 244) and Posttrauma syndrome (p. 245). For additional information, see other diagnoses under Major Trauma, as well as nursing diagnoses and interventions in the following sections, as appropriate: Hemodynamic Monitoring (p. 75), Prolonged Immobility (p. 149), Emotional and Spiritual Support of the Patient and Significant Others (p. 200), Peritonitis (p. 805), Enterocutaneous Fistula (p. 778), SIRS, Sepsis, and MODS, (p. 924), and Acid Base Imbalances (p. 1).

Acute cardiac tamponade

Pathophysiology

Potential causes of cardiac tamponade include the following:

• Trauma: blunt or penetrating cardiac trauma

• Iatrogenic: cardiac surgery, cardiac catheterization, pacemaker implant

• Nontraumatic hemorrhage: dissecting aortic aneurysm, anticoagulation therapy

• Left ventricular rupture: following extensive myocardial infarction

• Infection: viral, bacterial, or fungal

• Neoplasms/carcinoma: most commonly breast and lung

• Other: connective tissue disease, pleural effusions, radiation therapy, uremic states

Acute cardiac tamponade is usually the result of trauma, iatrogenic causes, and hemorrhage. Subacute tamponade causes are related to the slower accumulation of fluids seen with infections, neoplasms, and tissue disease. Occult or low pressure tamponade is seen in hypovolemic settings. Regional tamponade can occur with large pleural effusions or with any loculated fluid within the pericardial space. Pericardial effusions can be described using the Horowitz classification system based on the echo-free space seen with echocardiograms (Box 3-4). One must be aware that any nonacute tamponade may become acute when rapid deterioration in patient condition related to low CO occurs and requires emergent care.

Assessment: acute cardiac tamponade

Observation

• Early signs and symptoms: Muffled or distant heart tones, distended neck veins, hypotension (Beck triad), pulsus paradoxes, and unwillingness to lay flat/supine, anxiety, dyspnea, change in sensorium

• Early hemodynamic changes: Decreased BP, increase in RA pressure (RAP) or CVP. Pulsus paradoxus of greater than 10 mm Hg (see Box 3-2); low CO

• Late signs and symptoms: Signs of cardiogenic shock including decreased BP, weak or thready pulse, confusion, restlessness, cold clammy skin, pallor

• Late-stage hemodynamic changes: Continued hypotension, low CO, right and left atrial pressures equalize, and pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) increases

Vital signs

• Sinus tachycardia, commonly seen as compensatory response to decreased stroke volume

• Monitor BP; assess for significant hypotension, narrow pulse pressure, systolic BP less than 90, and pulsus paradoxus. Pulsus paradoxus is a drop of greater than 10 mm Hg in the systolic BP during inspiration and results from the decreased stroke volume with increased intrathoracic pressure.

• Exertional dyspnea early progressing to dyspnea and orthopnea

• Hoarseness and hiccups may be present due to laryngeal and phrenic nerve involvement.

• Low urine output is the result of low CO and taken with other signs should be viewed as a signal for intervention in the absence of hemodynamic monitoring.

Auscultation

• Beck triad of muffled or distant heart tones, distended neck veins, and hypotension, although described as classic, are seen in 10% to 33% of patients. Muffled heart tones may not be apparent with the patient sitting upright, depending on the volume of tamponade. JVD is not always present in acute tamponade, as it is commonly seen in constrictive pericarditis. In the presence of hypovolemia, blood flowing toward the RA during inspiration makes the finding of JVD less likely. Pericardial friction rub may be heard with pericarditis.

Hemodynamic monitoring

• Decreased BP: SBP less than 90 mm Hg requires intervention

• Increased CVP: Greater than 12 mm Hg

• Pulsus paradoxus: Greater than 10 mm Hg; easily seen in arterial waveform with lower systolic BP during inspiration

• Absence of Kussmaul sign: Kussmaul sign is the absence of a decline in jugular venous pressure during inspiration. Because the RV can accommodate increased volume with inspiration in tamponade, a decline in the jugular venous pressure can be seen. This is significant as to differentiate tamponade from constrictive pericarditis.

• Pulmonary artery pressure (PAP): Increased

• CVP equalizes with left atrial pressure (LAP) or pulmonary artery occlusive pressure (PAOP).

• BP, CO, and CI continue to decrease, requiring fluid and vasopressor and inotropic support until definitive treatment is provided.

• If untreated, tamponade can lead to PEA or total cardiac arrest.

• Pulsus paradoxus related to hypovolemia will resolve with fluid administration.

• Pulsus paradoxus will not resolve in acute cardiac tamponade with fluid administration alone.

Screening diagnostic tests

| Diagnostic Tests for Acute Cardiac Tamponade | ||

|---|---|---|

| Test | Purpose | Abnormal Findings |

| Electrocardiogram (ECG): 12 lead | Assess for any ischemia or infarct, underlying rhythm disturbances, or pericarditis. | Electrical alternans is a beat-to-beat change in the QRS, from swinging of the heart within the pericardium. It is rare and seen with very large volume effusions. Presence of ST-segment depression or T-wave inversion (myocardial ischemia), ST elevation (acute myocardial infarction), new bundle branch block (especially left bundle branch block), or pathologic Q waves (resolving/resolved myocardial infarction) in two contiguous or related leads. Pericarditis shows ST-segment and T-wave changes, which are often confused with ischemic changes but are more diffuse and follow a four-stage pattern (Table 5-9). Low voltage of QRS highly indicative of tamponade |

| Radiology | ||

| Chest radiograph (CXR) | Assess for a widening mediastinum. Assess size of heart, thoracic cage (for fractures), thoracic aorta (for aneurysm), and lungs (pneumonia, pneumothorax); assists with differential diagnosis of chest pain. | Widening mediastinum is indicative of acute cardiac tamponade, especially important for trauma, postprocedural, and postsurgical patients. Cardiac silhouette enlargement with clear lung fields is indicative of pericardial effusion; but >200 ml of fluid must be present for this finding to be apparent. |

| Echocardiography (2D or Doppler ECHO) |

It is the most definitive test for diagnosing early cardiac tamponade. Assessment of thoracic aneurysms that might have dissected into the valve or coronary arteries causing tamponade. Determine type of fluid within the pericardial space. Assess for mechanical abnormalities related to effective pumping of blood from both sides of the heart. |

Pericardial effusions with and without tamponade. Aortic dissections and aneurysms. Abnormal ventricular wall movement or motion, low ejection fraction, incompetent or stenosed heart valves, abnormal intracardiac chamber pressures |

| Transesophageal ECHO | Post cardiac surgery effusions often accumulate at the posterior wall with compression of RA. Useful for assessment of regional cardiac tamponade. Also can be done without delay while patient is being prepped in operating room for emergent thoracotomy or can be done in operating room. Assess for mechanical abnormalities related to ineffective pumping of blood from both sides of the heart using a transducer attached to an endoscope. | Same as above but can provide enhanced views, particularly of the posterior wall of the heart. |

| Blood Studies | ||

| Complete blood count (CBC) Hemoglobin (Hgb) Hematocrit (Hct) RBC count (RBCs) WBC count (WBCs) Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) |

Assess for anemia, inflammation, and infection; assists with differential diagnosis of cause of tamponade. | Decreased RBCs, Hgb, or Hct reflects hemorrhage or anemia. Elevated WBC and or ESR indicative of infection or inflammatory pericarditis unless secondary to uremia. |

| Coagulation profile Prothrombin time (PT) with international normalized ratio (INR) Partial thromboplastin time (PTT) Fibrinogen D-dimer |

Assess for causes of bleeding, clotting, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) indicative of abnormal clotting present in shock or ensuing shock. Anticoagulated patients are at higher risk for tamponade with procedures. |

Elevated PTT, PT with high INR promotes bleeding; elevated fibrinogen and D-dimer reflect abnormal clotting is present. |

| Electrolytes Potassium (K+) Magnesium (Mg2+) Calcium (Ca2+) Sodium (Na+) |

Assess for possible causes of dysrhythmias and/or heart failure. | Decrease in K+, Mg2+, or Ca2+ may cause dysrhythmias. Elevation of Na+ may indicate dehydration (blood is more coagulable). Low Na+ may indicate fluid retention and/or heart failure. |

| Other C-reactive protein (CRP) Anti–streptolysin O (ASO) |

Assess for cause of pericarditis. | CRP can be indicative of inflammation unless patient has uremia. ASO elevated with immunologic cause. |

Collaborative management

| Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Disease from the Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology | |

| In 2004, findings were published from the Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases in the European Heart Journal. These findings included specific recommendations for various forms of pericardial disease to include cardiac tamponade. The treatment guidelines have been widely cited in the worldwide medical literature. The following are limited to the recommendations for the treatment of acute (surgical) cardiac tamponade. | |

| Intervention | Rationale |

| The diagnostic tests as presented reflect these guidelines with the addition of CT, spin-echo, and cine MRI. | To assess the size and extent of simple and complex pericardial effusions. These are also helpful to measure the size of very large effusions. |

| Pericardiocentesis (Class I) | Absolute indication for cardiac tamponade with hemodynamic instability |

| Surgical drainage with bleeding suppression (Class I) | For wounds, ruptured ventricular aneurysm, or dissecting aorta aneurysm with hemorrhage or any tamponade in which needle clotting would make needle evacuation impossible |

| Thoracoscopic drainage, subxiphoid window, or open surgery | Indicated for loculated tamponade |

| In 2003, the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) presented a task force recommendation for the use of echocardiography for all patients with pericardial disease. This recommendation would include the cardiac tamponade patient unless an emergent surgical procedure was needed prior to evaluation. | |

From www.acc.org/qualityandscience/clinical/statements.htm

Care priorities

Medications used to increase the BP by stimulating vasoconstriction in the peripheral vasculature include neosynephrine or norepinephrine. These medications are less effective in a setting of hypovolemia.

6. Administer inotropic agents:

Medications used to increase myocardial contractility and CO include dopamine, dobutamine, and milrinone (see Appendix 6).

7. Stabilize bp with ongoing titration of medications and fluids:

CARE PLANS: ACUTE CARDIAC TAMPONADE

related to decreased preload secondary to compression of ventricles by fluid in the pericardial sac

Cardiac care: acute hemodynamic regulation

1. Assess cardiovascular function by evaluating heart sounds and neck veins hourly. Consult physician for muffled heart sounds, new murmurs, new gallops, irregularities in rate and rhythm, and distended neck veins.

2. Monitor all patients with blunt or penetrating trauma to the chest and abdomen for physical signs of acute cardiac tamponade, persistent hemodynamic instability, and shock symptoms more severe than expected for the blood loss.

3. Evaluate patient for pulsus paradoxus: an abnormal decrease in arterial systolic BP during inspiration compared with that during expiration of greater than 10 mm Hg difference (see Box 3-2).

4. Measure and record hemodynamic parameters. Consult physician or midlevel practitioner for sudden abnormalities or changes in trend. Early signs of tamponade include elevated CVP with normal BP and pulsus paradoxus. Later signs include equalization of CVP and LAP (PAOP) and elevated PAP in the presence of hypotension and low CO and CI (see Box 3-4).

5. Evaluate ECG for ST-segment changes, T-wave changes, rate, and rhythm. The optimum is sinus rhythm or sinus tachycardia. Maintain continuous cardiac monitoring.

6. For patients presenting with PEA and narrow-complex tachycardia on ECG, have a high suspicion of acute cardiac tamponade as the cause and follow ACLS guidelines.

7. Administer blood products, colloids, or crystalloids as prescribed. For trauma patients, use large-bore IV lines in the periphery, if possible. Use pressure infusers and rapid-volume/warmer infusers for patients who require massive fluid resuscitation.

8. Be prepared to administer vasopressor agents (e.g., norepinephrine, phenylephrine, dopamine) if fluid resuscitation does not support patient’s BP. Positive isotropic agents (e.g., milrinone) may be used to support CO in short-term management. The underlying problem is decreased ventricular filling, so these are temporizing measures for hemodynamic support until correction of the tamponade occurs.

9. Have emergency equipment available for immediate pulmonary artery catheterization, central line insertion, arterial line insertion, pericardiocentesis, or thoracotomy.

10. Assess heart rate and monitor ECG: sinus tachycardia, commonly seen as compensatory response to decreased stroke volume.

Ineffective tissue perfusion: pulmonary, peripheral, and cerebral

1. Assess tissue perfusion by evaluating the following at least hourly: level of consciousness (LOC), BP, pulses, pupillary response, skin temperature, and capillary refill.

2. Evaluate urine output hourly to ensure that it is at least 0.5 ml/kg/hr.

3. Maintain tissue perfusion by delivering prescribed blood products, colloids, crystalloids, vasopressors, and positive inotropes.

4. If hypotension occurs: ensure hypovolemia is treated, with fluid administration, prior to or simultaneously with vasopressors for treatment of hypotension. Administer vasopressors via central line whenever possible. Frequently assess peripheral IV lines for evidence of infiltration. If vasopressor agents infiltrate subcutaneous tissues, necrosis occurs. Follow appropriate management protocol for your institution.

5. Have emergency oxygen and intubation and mechanical ventilation equipment available.

6. Anticipate and prepare for emergent surgery and pericardiocentesis evacuation, if needed.

Acute spinal cord injury

Pathophysiology

Mechanisms of injury to the spinal cord can be traumatic or nontraumatic. Traumatic injuries include MVCs, falls, sports injuries, or acts of violence (e.g., gunshot wounds or stabbings). These injuries are the result of mechanical forces that result in sudden flexion, hyperextension, vertebral fracture, compression of the cord, rotation of the cord, or direct injury to the cord as in a stabbing or gunshot wound. Nontraumatic injuries may be a result of vascular injury (aortic disruption or spinal artery occlusion), degenerative diseases (spondylosis), inflammatory events, neoplasms, or autoimmune diseases (multiple sclerosis). Injuries to the spinal cord regardless of mechanism of injury include concussion, contusion, laceration, transsection, hemorrhage, ischemia, and avascularization. See SCI classifications and terminology in Table 3-3.

Table 3-3 SPINAL CORD INJURY CLASSIFICATIONS AND TERMINOLOGY

| Type | Closed (blunt) Open (gunshot wound or stabbing) |

| Cause | Motor vehicle crashes, falls, sports-related injury, acts of violence |

| Site | Level of injury involved (cervical thoracic, lumbar, sacral) |

| Mechanism | Flexion (deceleration injury, backward fall, diving injury) Extension (whiplash or fall with hyperextension of neck) |

| Stability | Integrity of supporting anatomy including vertebral bodies, ligaments, articulating processes, and facet joints |

| Complete | Tetraplegia (quadraplegia) or paraplegia (absence of motor, sensory, and vasomotor function below the level of the injury) More frequently seen in cervical injuries |

| Incomplete | Sparing of some motor and sensory function below the level of the lesion More frequently seen in lumbar injuries |

Acute phase assessment

Observation and physical assessment findings

• Flaccid paralysis below the level of injury of all skeletal muscles with absence of deep tendon reflexes (DTRs)

• Loss of temperature control with development of anhidrosis (absence of sweating)

• Loss of proprioception (position sense)

• Loss of visceral and somatic sensation, and loss of the penile reflex

• Bowel and bladder paralysis resulting in urinary retention and fecal retention occurring along with GI shutdown resulting in paralytic ileus

| Level of Injury | Manifestation |

| C4 and above | Loss of muscle function, including respiratory function; fatal outcome unless ventilation is provided immediately |

| C4-C5 | Same as above; phrenic nerve may be spared; assisted ventilation; quadriplegia/tetraplegia |

| C6-C8 | Diaphragm and accessory muscles or respiration retained; movement of neck, shoulders, chest, and upper arms; quadriplegia |

| T1-T3 | Neck, chest, shoulder, arm, hand, and respiratory function retained; difficulty maintaining a sitting position; paraplegia |

| T4-T10 | More stability of trunk muscles; paraplegia |

| T11-L2 | Use of upper extremities, neck, and shoulders; some function of upper thigh; reflex emptying of bowel; males may have difficulty achieving and maintaining an erection; decreased seminal emission |

| L3-S1 | Reflex emptying of bowel/bladder; decreased/lack of ability to have an erection; decreased seminal emission; all muscle groups in upper body function; most muscles of lower extremities function |

| S2-S4 | Flaccid bowel and bladder; lower extremity weakness; all muscle groups function; no ability to have a reflex erection |

This syndrome involves injury to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord supplied by the anterior spinal artery and may be caused by an acute burst fracture, herniation of an intervertebral disk, or a vascular injury or occlusion due to trauma, clot, or surgical procedure such as aortic aneurysm repair.

The prognosis varies with each patient and depends on the degree of structural damage and edema.

• Preserved (UMN) or areflexive bladder (LMN)

• Erectile dysfunction (UMN) or anesthesia to sacral dermatomes (LMN)

• May exhibit hypertonicity, especially if the lesion is isolated and primarily UMN

• Muscle stretch reflex (deep tendon reflexes) demonstrate hyperreflexive and muscle tone is increased, causing spasticity.

• Pattern of LMN responses (flaccid paralysis, areflexia, and loss of muscle tone with muscle fasciculations)

• Diminished muscle strength in the lower extremities consistent with the involved nerve root (see later).

• Greater involvement in the lower lumbar and sacral roots based on the muscle group distribution innervated by the spinal nerve involved

• Sensation is diminished or lost to pinprick and light touch along the dermatome pattern of the nerve; often there is saddle anesthesia with diminished or absent sensation to the glans penis or clitoris.

• Anal sphincter tone may or may not be present.

• There may be a history of urinary retention or loss of bladder tone and incontinence.

• Diminished or absent muscle strength in the muscles listed next assists in localizing the injury.

Collaborative management

Care priorities

1. Immobilize the injured site:

Cervical collar and/or head blocks and backboard: The initial treatment for a suspected cervical spine injury.

Cervical traction: Once the injury has been diagnosed, cervical traction to immobilize and reduce the fracture or dislocation can be achieved in several ways including application of a cervical-thoracic orthotic (CTO), a halo device with vest, or a traction system using Gardner-Wells, Vinke, or Crutchfield tongs. In traction therapy, the tongs are inserted through the outer table of the skull and attached to ropes and pulleys with weights to achieve bony reduction and proper alignment. Cross-table lateral radiographs should be obtained until desired realignment of the vertebral bodies is achieved. Another alternative is a special frame or bed (e.g., RotoRest kinetic treatment table). The use of the CTO or halo device for skeletal fixation of the head and neck allows for earliest mobilization and rehabilitation if no surgery is needed.

Surgical intervention: During the immediate postinjury phase, surgery is controversial, and immediate or early surgery postinjury may have little effect on the neurologic outcome and the benefit-to-harm ratio is uncertain. Surgery may be performed (1) if the neurologic deficit is progressing—for example, if cord compression is imminent, in the presence of an expanding hematoma or neoplasm, (2) in the presence of compound fractures, (3) if there is a penetrating wound of the spine, (4) if bone fragments are localized in the spinal canal, or (5) if there is acute anterior spinal cord trauma. Surgeries may include decompression laminectomy, closed or open reduction of the fracture, or spinal fusion for stabilization. Once stabilization of the spine occurs, the patient can be mobilized unless contraindicated for other reasons.

![]() Respiratory insufficiency is a hallmark in SCI, and the more rostral the injury, the more likely it is that the injury will affect ventilation. The need for assisted ventilation is based on level of injury, ABG values, and the results of pulmonary function tests, pulmonary fluoroscopy, and physical assessment data. The need for mechanical ventilation is likely with injuries at C4 and above, patients older than 40, smokers, and patients with associated chest trauma and immersion injuries. Initially, the patient may require intubation and, later, tracheotomy. Persons with high cervical injury who survive the initial injury but have paralysis of the muscles of respiration may require permanent tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation.

Respiratory insufficiency is a hallmark in SCI, and the more rostral the injury, the more likely it is that the injury will affect ventilation. The need for assisted ventilation is based on level of injury, ABG values, and the results of pulmonary function tests, pulmonary fluoroscopy, and physical assessment data. The need for mechanical ventilation is likely with injuries at C4 and above, patients older than 40, smokers, and patients with associated chest trauma and immersion injuries. Initially, the patient may require intubation and, later, tracheotomy. Persons with high cervical injury who survive the initial injury but have paralysis of the muscles of respiration may require permanent tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation.

5. Manage vasodilation-induced hypovolemia:

In patients with neurogenic shock, blood volume is normal but the vascular space is enlarged, causing peripheral pooling, decreased venous return, and decreased CO. Careful fluid repletion, usually with crystalloids, is indicated. Pressor therapy is initiated for patients unresponsive to fluid volume replacement (see discussion under Pharmacotherapy, which follows). For fluid management in patients with multisystem trauma, see Major Trauma, p. 235.

Stool softeners (e.g., docusate sodium):

Prevent fecal impaction and distention of the bowel, which could stimulate an episode of AD.

12. Prevent infection, control inflammation and coagulation:

To prevent thrombophlebitis, DVT, and pulmonary emboli.

CARE PLANS: ACUTE SPINAL CORD INJURY

![]() Respiratory Status: Ventilation

Respiratory Status: Ventilation

1. Assess for signs of respiratory dysfunction: shallow, slow, or rapid respirations; poor cough; vital capacity less than 1 L; changes in sensorium; anxiety; restlessness; tachycardia; pallor; adventitious breath sounds (i.e., crackles, rhonchi), decreased or absent breath sounds (bronchial, bronchovesicular, vesicular), decreased tidal volume (less than 75% to 85% of predicted value) or vital capacity ( less than 1 L).

2. Monitor ABG studies; report abnormalities. Be particularly alert to PaO2 less than 60 mm Hg, PaCO2 greater than 50 mm Hg, and decreasing pH, inasmuch as these findings indicate the need for assisted ventilation possibly caused by atelectasis, pneumonia, or respiratory fatigue.

3. Monitor vital capacity at least q8h. If it is less than 1 L, PaO2/PaO2 ratio is ≤0.75, or copious secretions are present, intubation is recommended.

4. If patient does not require intubation with mechanical ventilation, implement the following measures to improve airway clearance:

5. Suction secretions as needed, and hyperoxygenate before suctioning.

6. Monitor patient for evidence of ascending cord edema: increasing difficulty with swallowing secretions or coughing, presence of respiratory stridor with retraction of accessory muscles of respiration, bradycardia, fluctuating BP, and increased motor and sensory loss at a higher level than the initial findings.

7. If patient has cranial tongs or traction with a halo apparatus in place, monitor patient’s respiratory status every 1 to 2 hours for the first 24 to 48 hours and then every 4 hours if patient’s condition is stable. Be alert to absent or adventitious breath sounds, and inspect chest movement to ensure that the vest is not restricting diaphragmatic movement.

8. If intubation via endotracheal tube or tracheostomy becomes necessary, explain the procedure to patient and significant others.

![]() Airway Management; Oxygen Therapy; Respiratory Monitoring; Mechanical Ventilation

Airway Management; Oxygen Therapy; Respiratory Monitoring; Mechanical Ventilation

Autonomic dysreflexia (ad) (or risk for same)

related to abnormal response of the autonomic nervous system to a stimulus

1. Assess for the classic triad of AD: throbbing headache, cutaneous vasodilation, and sweating above the level of injury. In addition, extremely elevated BP (e.g., ≥250 to 300/150 mm Hg), nasal stuffiness, flushed skin (above the level of the injury), blurred vision, nausea, bradycardia, and chest pain can occur. Be alert to the following signs of AD that occur below the level of injury: pilomotor erection, pallor, chills, and vasoconstriction.

2. Assess for cardiac dysrhythmias, via cardiac monitor during initial postinjury stage (2 weeks).