4 Trauma

Initial assessment

Primary survey

Table 4.1 outlines the priorities for the first few minutes of treating an injured patient. Each of the ‘ABCDE’ priorities is paired with an equally important task. The usual sequence of history, examination, investigation and treatment seen in non-emergency situations is abandoned. Treatment of immediately life-threatening conditions is instigated simultaneously with ongoing assessment.

| Airway | Cervical spine control |

| Breathing | 100% oxygen |

| Circulation: assess heart rate and blood pressure, establish IV access | Control of external haemorrhage |

| Disability (neurological state) | Pupils |

| Exposure: undress patient | Temperature control |

Airway

An airway problem may be suspected in the presence of:

• tachypnoea/agitation/use of accessory muscles of respiration

Breathing

Circulation

Note the heart rate and blood pressure. Pass two wide-bore cannulae in the antecubital fossae and commence infusion of 2000 mL of warm Hartmann’s solution. Subsequent management depends on the patient’s response to this initial fluid bolus (see ‘Shock’, Ch3 p50). Blood should be sent for full blood count, coagulation, cross-match, urea and electrolytes (U&E), glucose and amylase. Alcohol and other drugs may also be measured if indicated.

External haemorrhage should be controlled by direct pressure over the open wound.

Disability (neurological status)

The simplest assessment of consciousness is the AVPU scale:

If time permits, the more formal Glasgow Coma Score should be determined (see Table 4.5). Observe the pupils for dilatation and reactivity. A fixed, dilated pupil suggests an expanding intracranial haematoma or cerebral oedema (the third nerve becomes compressed along the edge of the tentorium cerebelli as the brain herniates downward, allowing unopposed sympathetic pupillary dilatation).

Shock

Shock is defined as acute circulatory collapse causing inadequate perfusion and resultant tissue hypoxia and is extremely common in trauma. Haemorrhagic shock is the most common cause in trauma. Other causes of shock and their clinical features are outlined in Table 3.3 (see pages 50-52).

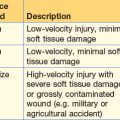

Haemorrhagic shock

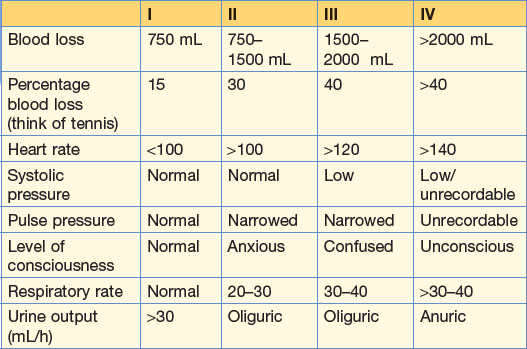

Haemorrhage is classified into four levels (Table 4.2), which are useful when estimating likely blood loss but are rarely clearly defined in practice. In true emergency situations patients are considered as responders, transient responders and non-responders, depending on the change in circulatory status following infusion of the initial bolus of 2000 mL warm crystalloid solution. Rapid responders who remain stable after the initial bolus do not need transfusion. Transient and non-responders need urgent blood transfusion and surgical intervention to identify and stem ongoing bleeding. When tracking down major haemorrhage in a hurry it is helpful to remember blood loss can only be in four places (and how to identify each in parentheses):

• chest (CXR, CT, in the chest drain)

• abdomen/pelvis (FAST ultrasound scan, X-ray of the pelvis, CT, DPL)

Blood in the chest, long bone fractures and major external haemorrhage are fairly easy to detect; most major occult blood loss is into the abdomen (see ‘Abdominal trauma’, p. 65).

Fluid resuscitation

When using crystalloid fluid for resuscitation, each unit volume of lost blood must be replaced by three times the volume of the crystalloid solution. Fully cross-matched blood is best for transfusion but takes time to prepare. Type-specific (ABO) blood is available much more quickly. Group O rhesus-negative blood is reserved for catastrophic exsanguinating haemorrhage (but see Box 4.2).

Box 4.2 Permissive hypotension/hypotensive haemostasis ‘The only way to stop the bleeding is to stop the bleeding’

There are several factors in haemorrhagic shock that challenge standard ATLS fluid-resuscitation:

Hypotension in haemorrhage is a natural protective mechanism

Hypotension facilitates in vivo coagulation

Hypotension secondary to haemorrhage can be tolerated for some time with moderately-well preserved cerebral and renal perfusion

Animal models have demonstrated that clot formed at the vessel bleeding point can be ‘pushed out’ at systolic pressures >80 mmHg

Aggressive fluid resuscitation with crystalloid has the following additional consequences:

Routes of administration of fluids

• Peripheral intravenous infusion – the most effective route for fast infusion of fluids is a wide-bore IV cannula in each antecubital fossa.

• Central line – percutaneous catheterisation of the femoral or internal jugular or subclavian veins allows central venous access. The long length of these catheters restricts the rate at which fluid may be given. Short, wide-bore peripheral lines are better.

• Venous cut-down – the long saphenous vein is easy to find just anterior to the medial malleolus or medial to the femoral pulse in the groin. It is quickly exposed through a small incision that permits catheterisation under direct vision. This technique is especially useful when all peripheral veins are collapsed and difficult to cannulate percutaneously.

• Intra-osseous needle (proximal tibia) – used for emergency resuscitation of children under 6 years of age, where no other access is available.

Chest trauma

Initial management follows the ABCDE protocol of the primary survey. Immediately life-threatening chest injuries that should be detected during the course of the primary survey are listed in Box 4.1 (p. 59).

Other chest injuries

While the ‘ATOM-FC’ (Box 4.1) injuries must be detected early, there are other thoracic problems that may not be obvious initially but which can be lethal if missed.

The chest X-ray in trauma

A systematic approach helps to detect all the useful information that a CXR provides for injured patients (Table 4.3). Rib fractures and pneumothoraces are more easily spotted if the film is rotated 90°.

| Lungs, pleural cavities, trachea and bronchi | Look for pneumothorax, haemothorax, pulmonary contusions, tracheal and bronchial disruptions. Since the patient is usually supine, even quite large haemothoraces may manifest only as a vague whitening of the lung field |

| Mediastinum | Widening of the mediastinum suggests aortic disruption. Air in the mediastinum may indicate oesophageal perforation |

| Diaphragm | Diaphragmatic rupture (usually on the left) Free gas under the diaphragm |

| Bones | Rib fractures, flail segments, scapular, sternum, clavicle and shoulder injuries. Fractures of the first rib and scapula are associated with high-velocity injuries and usually with serious organ damage. Lower left rib fractures raise the probability of splenic rupture |

| Soft tissues | Surgical emphysema is often seen with pneumothoraces |

| Tubes and lines | The positions of endotracheal, chest and nasogastric tubes and central venous line may all be checked on the CXR |

CT scanning and aortography may help confirm or exclude abnormalities suspected on the chest film.

Abdominal trauma

Examination

There are four things to check during the rectal examination:

Investigation

Table 4.4 outlines the advantages and disadvantages of ultrasound, diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) and CT scanning for abdominal trauma. For all but very unstable patients, CT scanning is by far the superior modality.

Table 4.4 Comparison of ultrasound, diagnostic peritoneal lavage and CT scanning for abdominal trauma

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound |

Treatment

Laparotomy

Indications for laparotomy include:

• persistent hypotension despite resuscitation where the blood loss is suspected to be abdominal; in these patients there is no time for complex investigations, they must be taken straight to theatre

• penetrating or gunshot wounds which obviously enter the peritoneal cavity

• radiological evidence of perforated viscus or severe organ damage.

Non-operative management

Accurate CT diagnosis of certain injuries, for example contained splenic haematoma or blunt renal trauma, may allow conservative treatment of conditions which would in the past have required surgery. Such patients need close monitoring (‘active re-observation’) and serial imaging with CT or ultrasound. See also Box 4.3.

Head injuries

Minor head injuries

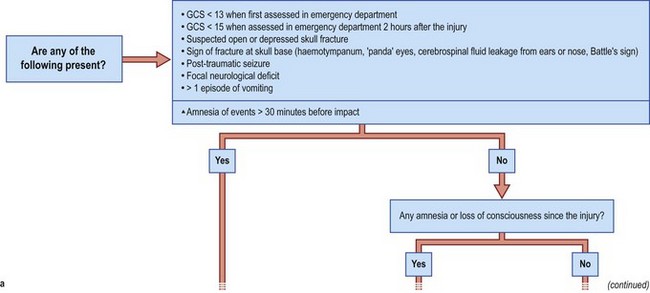

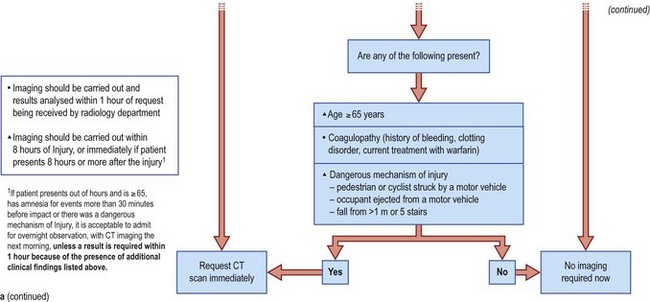

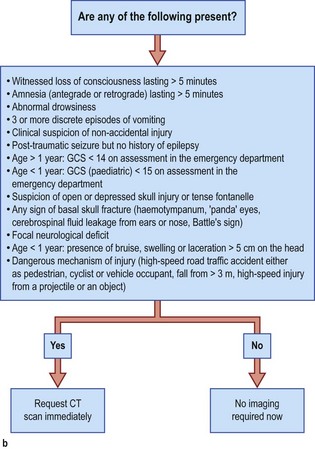

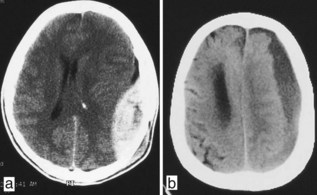

Those who were unconscious for longer periods, who have been drinking alcohol or have a skull fracture should be admitted for a minimum of 24 hours for neurological observation. Patients who have a clinical indication for admission (e.g. no carer at home) do not necessarily require skull X-rays; they simply require observation, with immediate CT scanning if they deteriorate (Fig. 4.1). CT has become the first-line investigation in head injury assessment.

Major head injuries

The Glasgow Coma Score (Table 4.5) is a reproducible way of quantifying depression of consciousness and should be assessed in all significant head injuries.

| A normal individual scores 15, whilst a corpse still scores 3. |

| Anyone with a score under 8 is by definition in coma and requires intubation and urgent CT scan |

| Score | |

|---|---|

| Best motor response | |

| Obeys commands | 6 |

| Localises pain | 5 |

| Withdraws to pain | 4 |

| Flexes to pain | 3 |

| Extends to pain | 2 |

| None | 1 |

| Speech | |

| Normal | 5 |

| Confused | 4 |

| Inappropriate | 3 |

| Incomprehensible sounds (grunts etc.) | 2 |

| None | 1 |

| Eyes | |

| Open spontaneously | 4 |

| Open to command | 3 |

| Open to pain | 2 |

| None | 1 |

Prognosis

See Table 4.6. Hypotension is thought to have particular relevance: intracranial perfusion pressure = MAP−ICP.

| Status | Percentage of patients |

|---|---|

| Complete recovery | 30 |

| Some disablement but able to look after themselves | 20 |

| Severe disablement: vegetative state or unable to care for themselves | 10 |

| Death | 40 |

Spinal injuries

Types of spinal injury

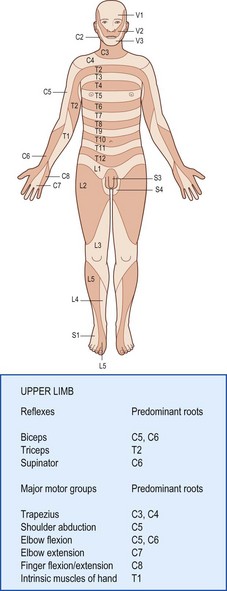

Damage below the cervical spine spares the arms (see Fig. 4.3); lesions above C3 paralyse the diaphragm and are lethal without immediate ventilation (e.g. the ‘hangman’s fracture’; fracture dislocation of C2 on C3).

Burns

Examination

Area

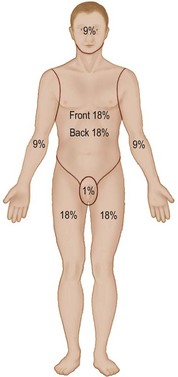

The ‘rule of nines’ is most convenient (Fig. 4.4). Alternatively the palm of an individual accounts for 1% of their surface area. For infants a Lund–Browder chart is used.

Trauma in pregnancy

Initial X-rays should still be obtained since the benefit to the fetus outweighs the small risk.