Chapter 14 Trauma

Trauma in Australia and New Zealand is the leading cause of death in the first four decades of life. Fortunately, injury-related deaths have declined over the past 20 years; however, they continue to be a significant burden on health resources. The identification and management of seriously ill patients requires a coordinated approach that includes pre-hospital management, emergency management and definitive surgical care. The development of the Early Management of Severe Trauma Course and the Definitive Surgical Trauma Course, both available in Australia and New Zealand, has provided the platform for improved trauma management.

PRE-HOSPITAL TRIAGE

Pre-hospital assessment and management by ambulance services now enables the initial triage of patients to regional or major trauma services. The overriding goal is to get the right patient to the right hospital at the right time. Patients meeting the following criteria should be considered as having potentially life-threatening injuries requiring the services of an appropriately designated trauma centre. These criteria are also used by many hospitals as triggers to activate a trauma team response for an incoming patient, and include:

The definition of serious trauma to any body region includes the following.

PREPARATION

M Mechanism, e.g. fall, motor vehicle accident, pedestrian

I Injuries, e.g. abdominal tenderness, chest injury, fractured long bone

S Signs, e.g. pulse, systolic blood pressure, respiratory rate, conscious level

T Treatment, e.g. cervical spine immobilisation, oxygen, intravenous therapy, drugs

This information enables the trauma team to prepare and focus their attention on specific early interventions that may be life-saving for the given situation. For example, the multitrauma victim with abdominal injuries who remains hypotensive after 2 litres of intravenous fluids in the field will need uncrossmatched group O blood via a rapid warmer to be available on arrival and will probably require early transfer to the operating suite for definitive care.

PRIMARY SURVEY

3 Circulation and control of external haemorrhage

Examination

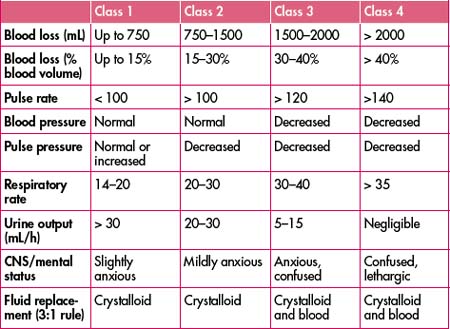

Assessment of a patient’s circulatory status does not require waiting for the blood pressure reading. Information gained from examination of the patient’s pulse, skin and level of consciousness is enough to make immediate resuscitation decisions, and the only equipment required is your eyes and your fingers. Remember to interpret your findings in the context of each individual you are assessing—the young, fit male who can compensate well despite considerable blood loss versus the elderly female with multiple comorbidities on numerous physiology-altering medications are two entirely different scenarios. Beware of patients who are hypotensive in the supine position—they have lost in excess of 30–40% of their blood volume and will require urgent resuscitation (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1 Estimated fluid and blood losses based on patient’s initial presentation (for a 70-kg patient)

Level of consciousness. A decreased level of consciousness is an indicator of poor cerebral perfusion and, again, is presumed to be due to hypovolaemia until proven otherwise.

Priorities

Deteriorating haemodynamic status may be due to:

Major blood loss can occur from the following five sites:

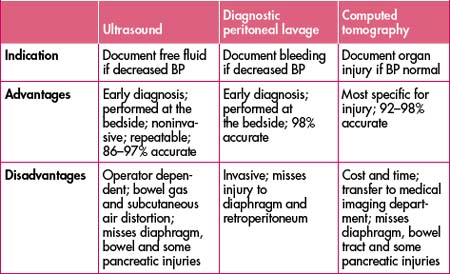

Always remember, however, that the patient may bleed into multiple sites simultaneously, making such an ‘orderly’ assessment difficult in practical terms. The role of bedside ultrasonograpy as an adjunct to the clinical examination in the trauma patient has been developing for many years throughout the world and is rapidly expanding in Australia, replacing diagnostic peritoneal lavage in many centres. It has the advantage of being rapid, safe, non-invasive and, most importantly, repeatable.

Code Crimson activation can be simplified to the following four steps:

Remember: It is a rule-in test—if it is negative all bets are off.

4 Disability: brief neurological examination

All patients with a GCS of less than 12 should have aggressive ABC management, including consideration for early intubation. This will enable controlled ventilation/oxygenation and allow the team to focus on the circulatory status, thus attending to two key factors responsible for adverse outcomes in traumatic brain injury—hypoxaemia and hypotension.

RESUSCITATION

Consider tetanus immunisation and prophylactic antibiotics as required.

The ongoing resuscitation status should be monitored by:

Persistent haemodynamic instability should again raise the possibility of:

MANAGEMENT OF LIFE-THREATENING CONDITIONS

As previously stated, life-threatening conditions should be suspected and identified during the primary survey. The management of these conditions may be based in the emergency department or may require immediate transfer to the operating suite.

Cardiac tamponade

The diagnosis should be suspected clinically and confirmed with FAST ultrasound if possible. Management revolves around adequate resuscitation and performing a left anterolateral thoracotomy to release the fluid within the pericardial sac. This should be undertaken by the most experienced trauma team member. Needle pericardiocentesis should only be considered in smaller hospitals if experienced staff are not available. Needle pericardiocentesis may be life-saving but rarely drains the pericardial sac adequately and is associated with significant complications.

HISTORY

M Medications—particularly anticoagulants!

P Past history—particularly diseases that alter clotting ability; pregnancy

L Last food/fluid; last tetanus injection

Specific injuries may be predicted from the mechanism of injury.

1 Injuries in motor vehicle crashes

2 Injuries in pedestrian–motor vehicle accidents

Again, pre-hospital information that gives some idea of the energy transfer involved is important.

3 Injuries in falls

5 Injuries in assaults

Knowledge of the mechanism of injury provides ‘advanced warning’ regarding possible injuries—it is a useful guide, but remember there are always exceptions.

SPECIFIC INJURIES

Head trauma

(See also Chapter 15, ‘Neurosurgical emergencies’.)

Traumatic brain injury is common. Unfortunately, despite this fact, there is a scarcity of good evidence in the literature upon which to base investigation and management decisions, particularly with regard to the patient with mild head injury. It is important to determine at an early stage whether your facility can provide the appropriate care necessary for the patient’s severity of injury or whether urgent transfer to another hospital will provide the best possible care.

Severe head injury

Neck injuries

Key points in management include:

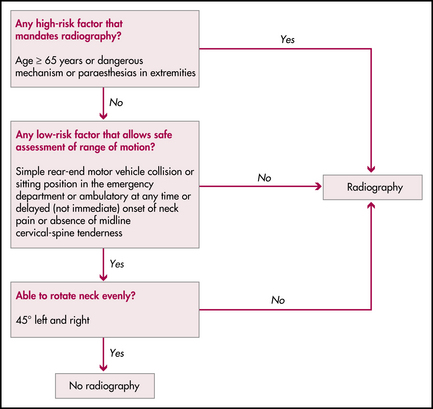

Alternative guideline for clearing the cervical spine is the Canadian C-spine rule; see Figure 14.1.

Abdominal trauma

Blunt abdominal trauma

Key points in the management include:

Penetrating abdominal trauma

Advice regarding resuscitation and imaging is as for blunt trauma (see above). Other important points include:

Thoracic trauma

Often when the patient first arrives, the examination and chest X-ray are performed in the supine position, and allowances must be made for this in terms of exam technique and film interpretation. For example, percussion should be performed in an anterior to posterior direction for detecting the presence of a haemothorax—and the chest X-ray will have a generalised increase in radiodensity on the affected side as compared to the usual meniscus on an erect film. Watch out for the patient with a widened mediastinum on chest X-ray suspicious for a contained rupture of the aorta—if you don’t have cardiothoracic facilities, transfer the patient without delay so further investigation and treatment can take place at the right hospital.

Traumatic diaphragmatic injury. Often missed; interpret X-rays with care. Early surgical consultation is important.

Pelvic trauma

Pelvic injuries can range in severity from simple pubic rami fractures to unstable injuries with associated life-threatening exsanguination. It is important to appreciate the magnitude of force required to fracture the pelvis—and hence the high association with other potentially life-threatening injuries.

Three common mechanisms of injury are:

Important points in the management of these injuries include:

Musculoskeletal trauma

Musculoskeletal trauma is very common. Fortunately most injuries are neither limb- nor life-threatening, although they can on occasion look very dramatic. It is important not to be distracted by the injury and to manage all these patients in an orderly fashion with meticulous attention to the ABCs first. Some important points in the management of such injuries include:

Compartment syndrome

DEFINITIVE CARE

Trauma service performance improvement

Clinical indicators

Clinical indicators are measures of the process or outcomes of care. They are not designed to be exact standards, but rather act as ‘flags’ to alert clinicians to possible problems in the system or opportunities for improvement. For clinical indicators to be effective they must be relevant and clearly defined. Development of a set of clinical indicators is interactive. Indicators are reviewed on an ongoing basis with reference to the usefulness of the data and the resources required to collect it. Trauma service indicators are used to monitor process and outcomes of care from the pre-hospital phase through to rehabilitation and discharge. Close analysis of data is required as there may be valid reasons why an event occurs differently from an expectation.

Examples of trauma service clinical indicators are:

American College of Surgeons. Trauma performance improvement: a reference manual. Online. Available: http://www.facs.org/dept/trauma/handbook.html; 2002.

American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Advanced trauma life support—faculty manual, 7th edn. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2004.

Curtis K., Ramsden C., Friendship J. Emergency and trauma nursing. Mosby Australia. 2007.

Ferrera P.C., Colucciello S.A., Marx J.A., et al. Trauma management—an emergency medicine approach. St Louis: Mosby; 2001.

Hoffman J.R., Mower W.R., Wolfson A.B., et al. for The National Emergency X-radiography Utilization Study Group. Validity of a set of clinical criteria to rule out injury to the cervical spine in patients with blunt trauma. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(2):94-99.

Holcomb J.B., et al. Damage control resuscitation: directly addressing the early coagulopathy of trauma. J Trauma. 2007;62:307-310.

NSW Health Department. Easy guide to clinical practice improvement. A guide for health professionals. Online. Available: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/quality/files/cpi_easyguide.pdf; 2002.

NSW Health Department. The clinician’s toolkit for improving patient care, 1st edn. Sydney: NSW Health Department; 2001.

St Vincent’s Hospital trauma handbook. 4th edn, St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney, 2002.

Stiell I.G., et al. The Canadian C-Spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2510-2518.