CHAPTER 12 TRAUMA

PRIMARY SURVEY

The principal elements of the primary survey are A, B, C and D, as follows.

(B) Breathing

Support ventilation if necessary. Expose the chest and examine for adequacy of respiration. Identify and treat life-threatening conditions such as flail chest, open wounds, tension pneumothorax or massive haemothorax.

(C) Circulation

Insert two 14-gauge peripheral intravenous cannulae. If this is not possible, then cannulate the internal jugular or femoral vein, or consider peripheral venous cut-down (e.g. saphenous vein). In ATLS doctrine, CVP lines are used for monitoring and not for resuscitation purposes. Adapt practice dependent on local skills, kit and expertise.

Insert two 14-gauge peripheral intravenous cannulae. If this is not possible, then cannulate the internal jugular or femoral vein, or consider peripheral venous cut-down (e.g. saphenous vein). In ATLS doctrine, CVP lines are used for monitoring and not for resuscitation purposes. Adapt practice dependent on local skills, kit and expertise. Commence fluid resuscitation with 2–3 L of crystalloid. If there is an ongoing fluid requirement, continue with blood / blood products. Colloids remain controversial in this setting, with growing evidence they may contribute to increased bleeding. Fully cross-matched blood is preferable but group-specific, or non-cross-matched O negative can be used, depending upon circumstances.

Commence fluid resuscitation with 2–3 L of crystalloid. If there is an ongoing fluid requirement, continue with blood / blood products. Colloids remain controversial in this setting, with growing evidence they may contribute to increased bleeding. Fully cross-matched blood is preferable but group-specific, or non-cross-matched O negative can be used, depending upon circumstances.EXPOSURE AND SECONDARY SURVEY

Once the initial survey is complete and the patient is stabilized, ensure that appropriate monitoring is established and that necessary investigations have been organized (Box 12.1).

Box 12.1 Investigations and monitoring

| Routine investigations | Monitoring |

|---|---|

| FBC | ECG |

| U&Es, glucose | Blood pressure (non-invasive or invasive) |

| Arterial blood gases | Pulse oximeter |

| (Pregnancy test) | CVP |

| ECG | Urine output |

| Lateral cervical spine X-ray | |

| Chest X-ray | |

| Pelvic X-ray | |

| Urine (stick test) |

Ultrasound is increasingly used to identify free fluid (blood) in the peritoneal, pleural and pericardial spaces. In this context, its value is in identifying a problem (e.g. peritoneal fluid) rather than the definitive diagnosis (e.g. ruptured spleen). There is much current interest in the use of ‘focused’ ultrasound examinations in trauma, which are easily learned and reliably performed by non-specialist medical staff (e.g. the ‘FAST’ scan) (Trauma Ultrasonography. The FAST and Beyond. http://www.trauma.org/archive/radiology/FASTintro.html).

INTENSIVE CARE MANAGEMENT

Multiple organ failure

Multiple organ failure is common after massive trauma. Typically patients develop a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), 24–48 h after apparently adequate resuscitation, which then progresses to multiple organ failure. Tissue damage, activation of the immune system and massive blood transfusion are all implicated but exact mechanisms are still not fully understood. Treatment is largely supportive. Possible sources of any ongoing inflammatory response, including necrotic tissue and foci of infection, must be excluded. (See Multiple organ failure, p. 329, and SIRS, p. 326.)

The management of specific groups of injuries is discussed below.

HEAD, FACE AND NECK INJURIES

Cervical soft-tissue injury

Direct injury to soft tissues of the neck can result in airway compromise, due either to haematoma / tissue swelling causing compression of the airway or to direct injury to the larynx or trachea. Secure the airway by early intubation and seek expert surgical help. Vascular injuries in the neck may compromise the cerebral circulation. Dissection of the carotid arteries by blunt injury from seatbelts or other trauma is rare but easily missed. Bleeding may track down into the chest, resulting in haemothorax or haemomediastinum and rarely cardiac tamponade. Carotid dissection can be identified using ultrasonography, CT scan or angiography.

SPINAL CORD INJURIES

Spinal cord injury may occur as a result of trauma, vertebral collapse, infection, tumours, infarcts and other pathologies. The classic features of complete spinal cord injury are total loss of motor and sensory function below the level of the injury. (In the acute setting, the apparent level of the injury may be higher than actual due to inflammation and oedema around the site of injury.) A number of patterns of incomplete injuries are also recognized (Table 12.1).

| Complete cord injury | Total paralysis and loss of sensation below level of injury |

| Cord hemisection, Brown–Séquard syndrome | Ipsilateral paralysis and contralateral loss of sensation below level of lesion |

| Central cord syndrome | Greater motor loss in upper limbs than lower. Variable sensory loss below level of lesion |

| Anterior cord syndrome | Paralysis, loss of pain / temperature sensation below level of lesion Proprioception and vibration preserved |

In all cases of significant trauma, assume that the spine (cervic, thoracic or lumbar) is injured until proven otherwise and immobilize it as part of initial resuscitation. Signs suggestive of spinal cord injury in an unconscious patient are given in Box 12.2.

Box 12.2 Signs suggestive of spinal cord injury in an unconscious patient

Diaphragmatic pattern of breathing

Unexplained hypotension / bradycardia

Management

Immobilize the spine to prevent secondary damage. Use a cervical collar, sandbags and tape for cervical spine, plus spinal board. (Log roll with inline stabilization to control head and neck movement.)

Immobilize the spine to prevent secondary damage. Use a cervical collar, sandbags and tape for cervical spine, plus spinal board. (Log roll with inline stabilization to control head and neck movement.) Sympathetic interruption from cord injury will produce hypotension and bradycardia, depending upon the level of cord injury. Vasopressors / inotropes may be required to maintain the circulation. Exclude haemorrhage from other injuries (e.g. in the ‘silent’ denervated abdomen).

Sympathetic interruption from cord injury will produce hypotension and bradycardia, depending upon the level of cord injury. Vasopressors / inotropes may be required to maintain the circulation. Exclude haemorrhage from other injuries (e.g. in the ‘silent’ denervated abdomen). Tracheal intubation and assisted ventilation may be required for respiratory insufficiency or to facilitate surgery. Consider awake fibreoptic intubation using local anaesthesia. Alternatively, intubate the anaesthetized patient with inline immobilization of the neck. The use of a bougie and McCoy laryngoscope or video laryngoscopes limit the need to extend the neck.

Tracheal intubation and assisted ventilation may be required for respiratory insufficiency or to facilitate surgery. Consider awake fibreoptic intubation using local anaesthesia. Alternatively, intubate the anaesthetized patient with inline immobilization of the neck. The use of a bougie and McCoy laryngoscope or video laryngoscopes limit the need to extend the neck. Urinary retention is common (and is an important cause of spinal hyperreflexia). Pass a urinary catheter.

Urinary retention is common (and is an important cause of spinal hyperreflexia). Pass a urinary catheter. High-dose steroids (methylprednisolone), if given early, may have beneficial effects in spinal injury.

High-dose steroids (methylprednisolone), if given early, may have beneficial effects in spinal injury. Discuss the management with the local spinal injuries unit or spinal surgeon. The indications for early spinal decompression and surgical stabilization are controversial. Transfer to a spinal injury unit only after exclusion and stabilization of other injuries in a general / neurosurgical unit.

Discuss the management with the local spinal injuries unit or spinal surgeon. The indications for early spinal decompression and surgical stabilization are controversial. Transfer to a spinal injury unit only after exclusion and stabilization of other injuries in a general / neurosurgical unit.THORACIC INJURIES

Rib fractures

These are significant because of the potential for injury to the underlying viscera. Elderly patients with brittle ribs may have impressive rib fractures with little underlying injury. Conversely, younger patients with more flexible ribs may have severe visceral injury without obvious fractures.

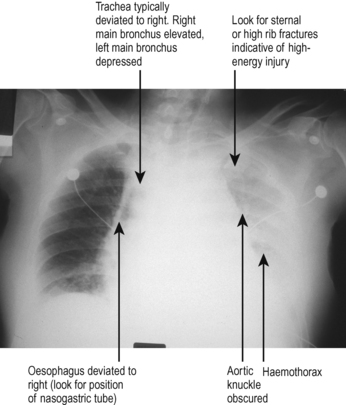

Mediastinal injury

Rapid deceleration injuries can result in injury to the mediastinal contents; in particular, traumatic transection of the aorta or other great vessels. Many patients with such injuries will die before reaching hospital, but some develop a contained rupture that is at risk of massive rebleeding at any time, hours or even days ahead. The typical finding is that of a widened mediastinum on CXR. Typical features are shown in Fig. 12.1.

The management of great vessel injury is increasingly by radiological stenting rather than open surgery, where such facilities exist. Refer the patient to cardiothoracic surgeons, vascular surgeons, or vascular interventional radiologists. Immediate management includes controlled hypotension (e.g. GTN or esmolol infusion).

Cardiac contusions

Blunt trauma to the anterior chest wall can result in injuries to the myocardium, coronary arteries, valves and other related structures. The presence of a fractured sternum should raise suspicion. Typically myocardial contusions may result in dysrhythmias and ischaemic injury patterns on ECG. These are often transient and not significant but dysrhythmias may require appropriate intervention. Rarely, injury to the anterior descending coronary artery may lead to myocardial infarction. Perform serial 12-lead ECGs and send blood for troponin. Echocardiography can indicate dyskinesia suggestive of myocardial contusion, valvular damage, and pericardial effusions. Transthoracic views may be sufficient, but have poor sensitivity for detecting aortic dissection or root injury. A transoesophageal echo or CT angiogram (where available) are valuable for excluding these diagnoses. Seek specialist advice.

ABDOMINAL INJURIES

Ruptured liver

Where possible, liver trauma is managed conservatively. Post-traumatic liver haemorrhage is often amenable to radiological intervention (embolization). Where laparotomy is unavoidable, surgeons may pack the liver bed and close the abdomen, with the aim of returning to theatre after 48 h. If haemodynamically stable, patients with liver rupture should be transferred to a specialist unit.

Abdominal compartment syndrome

If intra-abdominal pressure rises above venous pressure (e.g. as a result of intra-abdominal haemorrhage) then perfusion to the abdominal organs is impaired. The first indication may be a falling urine output in the presence of an increasingly tense and quiet abdomen. Intra-abdominal pressure can be measured by connecting the urinary catheter to a pressure transducer. Intra-abdominal pressures above 20 mmHg, together with evidence of end organ dysfunction, are suggestive of abdominal compartment syndrome. The management is surgical exploration (see p. 174).

SKELETAL INJURIES

Pelvic injuries

Urethral injury should be considered in all cases of pelvic injury. Suspect if there is bleeding from the urethral meatus or an abnormal rectal examination. Do not attempt urethral catheterization. Seek help from urologists. Diagnosis is by urethrogram, which can be performed in A&E. Contrast is injected via the urethra, looking for extravasation on X-ray. Management is by suprapubic catheter, with definitive repair at a later date.

FAT EMBOLISM

Investigations

The diagnosis is often one of exclusion. Fat droplets may be seen in retinal vessels, sputum or urine: none of these findings is specific for the condition. CT scan of the brain is usually normal or shows mild diffuse cerebral oedema; MRI scans show areas of microinfarction in severe cases.

PERIPHERAL COMPARTMENT SYNDROMES

Compartment syndrome may be caused by any process that leads to soft-tissue swelling, including infection, haemorrhage or ischaemia. Typical causes are shown in Box 12.3.

Box 12.3 Typical causes of peripheral compartment syndrome

Vascular injury (including surgery)

Diagnosis relies upon clinical suspicion. Look for swollen, tense and painful muscles (particularly on extension) in the calf and forearm. Remember pain may be masked by epidural / regional anaesthetic blocks. Pulses may be absent but are not invariably so. Diagnosis is confirmed by measurement of compartmental pressure, obtained by insertion of a 21-gauge (green) needle connected to a flush device and pressure transducer (as for any intravascular monitoring). It should be appreciated that there are multiple compartments in each limb so measurement requires knowledge of the appropriate anatomy (seek advice). Pressures greater than 30 mmHg are an indication for fasciotomy and debridement of dead muscle. This can be performed in the ICU. Wounds are left open, and closed subsequently when swelling subsides. Seek surgical advice.

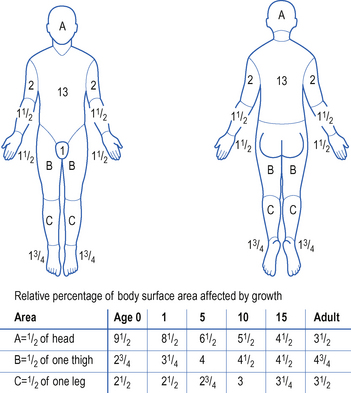

BURNS

Patients with extensive burn injuries (>20% body surface area) are usually managed in regional burns centres. You may, however, be called to help in the initial resuscitation of a burns victim or may be required to manage the patient in the general ICU because of other coexisting problems. A typical chart for the assessment of burn area is shown in Fig. 12.2.

Resuscitation

The basic principles of resuscitation of the burn victim are the same as for any other patient. The main problems relate to the potential for thermal injuries to the airway, large fluid losses and potential for infection.

Give humidified oxygen by face mask. If there are extensive facial burns, or any evidence of thermal injury to the airway, the airway should be secured by endotracheal intubation. This should be performed electively before oedema and swelling make intubation impossible.

Give humidified oxygen by face mask. If there are extensive facial burns, or any evidence of thermal injury to the airway, the airway should be secured by endotracheal intubation. This should be performed electively before oedema and swelling make intubation impossible. Establish i.v. access. Where possible, avoid siting cannulae through burned skin, to reduce the risk of infection. (Ultrasound is helpful to guide central venous cannulation if burns are extensive.)

Establish i.v. access. Where possible, avoid siting cannulae through burned skin, to reduce the risk of infection. (Ultrasound is helpful to guide central venous cannulation if burns are extensive.)The fluid requirements depend on the size of the burn. This is estimated from the rule of nines or from burns charts. A number of regimens are described for fluid replacement based on either crystalloid or colloid infusion. Examples are shown in Box 12.4.

Box 12.4 Examples of fluid regimens for the resuscitation of burns victims

| Mount Vernon formula | Parkland formula |

|---|---|

| 4.5% albumin | Ringer lactate |

| Volume (mL) = 0.5 × weight (kg) × % burn | Volume (mL) = 4 × weight (kg) × % burns |

| Over six consecutive periods of 4, 4, 4, 6, 6 and 12 h each | Given over 24 h |

ELECTROCUTION

NEAR DROWNING

Management

Establish invasive cardiovascular monitoring (arterial line and CVP) and support circulation as necessary.

Establish invasive cardiovascular monitoring (arterial line and CVP) and support circulation as necessary. If evidence of aspiration on CXR, consider broad-spectrum antibiotics (seek microbiological advice). Otherwise await cultures.

If evidence of aspiration on CXR, consider broad-spectrum antibiotics (seek microbiological advice). Otherwise await cultures.The degree of hypoxic brain injury is the main factor in quality of outcome following near drowning. Severe hypothermia can, however, provide significant brain protection, particularly in children, and therefore it can be difficult to predict outcomes. Good outcomes can occasionally be achieved despite prolonged periods of immersion and prolonged cardiac arrest. (See also Hypothermia, p. 226)

The cervical spine should be assumed to be unstable and must be protected at all times. Use in-line immobilization during airway manoeuvres. A cervical collar should be applied and sandbags and tape used to preventunnecessary movement of the cervical spine.

The cervical spine should be assumed to be unstable and must be protected at all times. Use in-line immobilization during airway manoeuvres. A cervical collar should be applied and sandbags and tape used to preventunnecessary movement of the cervical spine.

Evidence suggests that following trauma, early over aggressive fluid resuscitation may worsen outcome. Where surgical haemostasis cannot be immediately achieved, the goal of fluid resuscitation should be to only restore the circulating volume sufficiently to achieve a blood pressurecompatible with critical organ perfusion (see below).

Evidence suggests that following trauma, early over aggressive fluid resuscitation may worsen outcome. Where surgical haemostasis cannot be immediately achieved, the goal of fluid resuscitation should be to only restore the circulating volume sufficiently to achieve a blood pressurecompatible with critical organ perfusion (see below).

X-rays of the spine do not exclude instability resulting from ligament injury. Spinal cord damage can only befully excluded by clinical examination in an awake, co-operative patient. Therefore, even if X-rays are normal, you should maintain immobilization until the spine can be assessed clinically. CT or MRI can give further information.

X-rays of the spine do not exclude instability resulting from ligament injury. Spinal cord damage can only befully excluded by clinical examination in an awake, co-operative patient. Therefore, even if X-rays are normal, you should maintain immobilization until the spine can be assessed clinically. CT or MRI can give further information.

Suxamethonium can be used in the first few hours after injury. Avoid after 24 h because of the potential for massive K+ release. (See Suxamethonium, p. 43.)

Suxamethonium can be used in the first few hours after injury. Avoid after 24 h because of the potential for massive K+ release. (See Suxamethonium, p. 43.)