CHAPTER 31 Trapeziometacarpal Arthritis

ANATOMY

The anatomy of the thumb basilar joint is complex. This biconcave-convex saddle-shaped joint has minimal bony constraints, permitting a wide arc of mobility and facilitating prehension. The ligamentous structures about the elbow promote stability, and the muscular forces about the thumb confer large forces on the thumb in pinch and grasp.1 Basilar joint arthritis at the thumb is related to a variety of factors, including age and use, genetics, and hormonal effects. Bettinger and colleagues described the complex ligamentous structure about the trapeziometacarpal joint and 16 ligaments that stabilize the joint.2 The important anterior oblique (beak) ligament is considered the primary stabilizer of the trapeziometacarpal joint.3 Bettinger and coworkers described superficial and deep components of the beak ligament.2 The superficial and deep anterior oblique ligament, the dorsoradial ligament, the posterior oblique ligament, the ulnar collateral ligament, the intermetacarpal ligament, and the dorsal intermetacarpal ligament stabilize the thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) joint; the other nine ligaments stabilize the trapezium.2 The degree of anterior oblique ligament degeneration corresponded with the extent of arthritis4 in a cadaveric study. Laxity of the beak ligament may alter the contact pressures and congruity of the joint, leading to joint subluxation and arthritic changes.5

PATIENT EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

Examination may elicit the shoulder sign, in which the CMC joint is subluxated and the metacarpus adducted. The CMC grind test is performed by axial loading and circumduction of the metacarpal on the trapezium. Concomitant or alternative diagnoses should be ruled out; patients may have carpal tunnel syndrome (estimated to coexist in 43% of cases), deQuervain’s tendonitis, or hypermobility of the CMC joint.3,6 The status of the scaphotrapeziotrapeziod (STT) joint and arthritis in this joint should be assessed. Range of motion at the wrist and thumb should be documented, including thumb abduction and opposition (i.e., ability touch the base of the small finger) and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) motion. The MCP joint must be examined in hyperextension, which exacerbates metacarpal adduction. If MCP hyperextension is not addressed during ligament reconstruction, the stresses on the reconstruction may lead to failure. If hyperextension is greater than 30 degrees, the MCP joint should be treated with fusion, capsulodesis, or sesmoidectomy.7 If hyperextension is less than 30 degrees, the surgeon can consider pinning the MCP joint with a Kirschner wire for 4 to 6 weeks.

Diagnostic Imaging

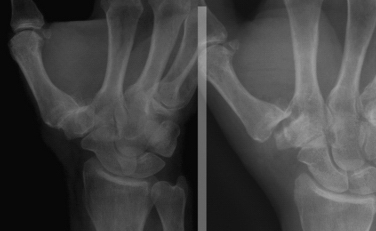

Radiographs that should be obtained include posteroanterior, lateral, and Bett’s views. From plain film radiographs, the extent of disease may be staged according to the system described by Eaton.8 However, it is important to consider the patient’s radiographic stage and symptoms together. Radiographs often demonstrate severe arthritis in a patient with only minimal symptoms; conversely, some patients have minimal changes on radiographs but are quite symptomatic.

TREATMENT

Eaton divided thumb CMC joint arthritis into stages, which are useful for deciding on treatment options.8 The stage I joint is essentially radiographically normal but may have slight widening caused by synovitis or effusion. It may be treated by conservative means, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and immobilization, but some authorities advocate ligament reconstruction, arthroscopy, or metacarpal osteotomy for stage I disease. Stage II disease is characterized by further joint space narrowing, changes with osteophyte formation (<2 mm), and mild to moderate joint subluxation. Stage III disease is characterized by moderate joint subluxation and prominent osteophyte formation (>2 mm), and stage IV is pantrapezial arthritis. Stages II through IV may be treated by arthroscopic or by open partial or complete trapeziectomy, with or without ligament reconstruction and interposition, fusion, or arthroplasty.

Patients with Eaton stage I, II, or III disease may be candidates for arthroscopy to determine the true extent of joint changes. In the early stages, in which the articular cartilage is intact but synovitic changes or ligamentous laxity is present, the pathology may be addressed by débridement and capsular shrinkage of the ligaments. Patients with more apparent changes, such as attenuation of the anterior oblique ligament and partial volar cartilage loss, may be candidates for extension osteotomy or arthroscopic débridement and interposition arthroplasty, whereas those with widespread cartilage loss may do best with arthroscopic débridement and interposition arthroplasty or conversion to an open procedure.9,10

Arthroscopic Technique

The technique for arthroscopy of the CMC joint has previously been described.11,12 The thumb is suspended in traction (Fig. 31-1), and surface landmarks are marked (Fig. 31-2). The joint is penetrated with a needle; fluoroscopy can help to confirm correct entry into the trapeziometacarpal joint rather than the STT joint. After the needle position is confirmed, the joint is insufflated with saline.

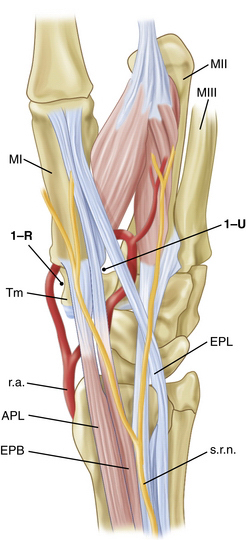

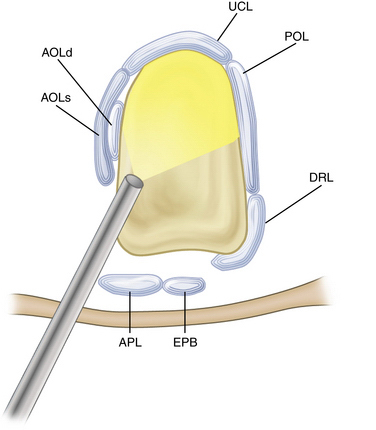

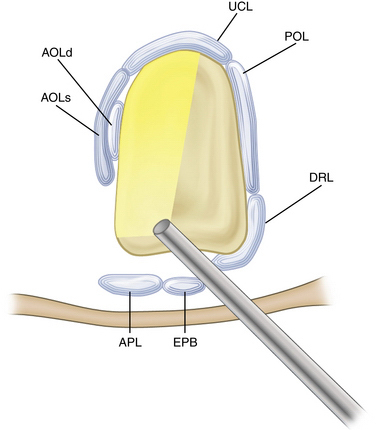

The 1-R (radial) and the 1-U (ulnar) portals are used (Fig. 31-3). The 1-R portal is made between the abductor pollicis longus and flexor carpi radialis tendons at the CMC joint level. The 1-R portal is useful to examine the dorsal radial, palmar oblique, and ulnar collateral ligaments, and it provides a view of the radial aspect of the joint. It also allows visualization of the intermetacarpal ligament and the distal insertions of the anterior oblique ligament into the first metacarpal (Fig. 31-4).

The 1-U portal is placed just ulnar to the extensor pollicis brevis tendon. This area can have a higher incidence of superficial radial nerve branches crossing the portal site than the 1-R portal area does. The radial artery is only a few millimeters from the ulnar side of the portal. Similar to the procedure used when establishing the 1-R portal, the skin should be carefully incised, and a small hemostat should be used to gently dissect and spread down to the capsular tissue. This helps to avoid traumatic injury to branches of the superficial radial nerve or the radial artery. The 1-U portal tends to enter the joint through the dorsal radial ligament or between the dorsal radial ligament and the palmar oblique ligament, and this portal allows visualization of the anterior oblique and ulnar collateral ligaments (Fig. 31-5). It may also be used as the main working portal for interventions after diagnostic arthroscopy.11

After the bony work has been completed, the interposition material is placed. Some surgeons have used autograft tissue, such as one half of the flexor carpi radialis tendon or the palmaris longus.12,13 Xenograft, allograft, or manufactured materials may be cut to match the articular surface area of the joint. Several commercial materials have been advocated for this purpose.14–17 The interposition material is placed into the joint with a small, curved hemostat through a portal.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

PITFALLS

CONCLUSIONS

Although limited data are available regarding outcomes after arthroscopic first CMC joint procedures, existing series document results similar to those for ligament reconstruction or ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition.9,10,12,14,17

1. Cooney WP3rd, Chao EY. Biomechanical analysis of static forces in the thumb during hand function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:27-36.

2. Bettinger PC, Linscheid RL, Berger RA, et al. An anatomic study of the stabilizing ligaments of the trapezium and trapeziometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24:786-798.

3. Eaton RG, Littler JW. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1655-1666.

4. Doerschuk SH, Hicks DG, Chinchilli VM, Pellegrini VDJr. Histopathology of the palmar beak ligament in trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24:496-504.

5. Pellegrini VDJr. Osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint: the pathophysiology of articular cartilage degeneration. I. Anatomy and pathology of the aging joint. J Hand Surg Am. 1991;16:967-974.

6. Florack TM, Miller RJ, Pellegrini VD, et al. The prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in patients with basal joint arthritis of the thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17:624-630.

7. Lourie GM. The role and implementation of metacarpophalangeal joint fusion and capsulodesis: indications and treatment alternatives. Hand Clin. 2001;17:255-260.

8. Eaton RG, Glickel SZ, Littler JW. Tendon interposition arthroplasty for degenerative arthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1985;10:645-654.

9. Badia A. Trapeziometacarpal arthroscopy: a classification and treatment algorithm. Hand Clin. 2006;22:153-163.

10. Badia A, Khanchandani P. Treatment of early basal joint arthritis using a combined arthroscopic débridement and metacarpal osteotomy. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2007;11:168-173.

11. Berger RA. A technique for arthroscopic evaluation of the first carpometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22:1077-1080.

12. Menon J. Arthroscopic management of trapeziometacarpal joint arthritis of the thumb. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:581-587.

13. Menon J. Arthroscopic evaluation of the first carpometacarpal joint, [comment]. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23:757.

14. Adams JE, Merten SM, Steinmann SP. Arthroscopic interposition arthroplasty of the first carpometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg Eur. 2007;32:268-274.

15. Adams JE, Steinmann SP. Interposition arthroplasty using an acellular dermal matrix scaffold. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73:319-326.

16. Adams JE, Steinmann SP, Culp RW. Trapezium-sparing options for thumb carpometacarpal joint arthritis. Am J Orthop. 2008;37(suppl 1):8-11.

17. Culp RW, Rekant MS. The role of arthroscopy in evaluating and treating trapeziometacarpal disease. Hand Clin. 2001;17:315-319.