Chapter 34 Transverse medial thigh lift

Introduction

The medial upper thigh area is often subject to ptosis and skin wrinkling, due to the thinness of the skin and the frequent fat deposition. The unsightly appearance of this region results in a number of patients, some as young as 35 years, seeking consultation and correction. Unfortunately, the transverse, superior and medial thigh lifts still have a poor reputation among plastic surgeons and patients alike due to the high complication rate and unsightly esthetic results. Complications previously encountered with traditional procedures included scar visibility at the upper aspect of the thigh, vulvar dehiscence, hypertrophic scarring mainly in the gluteal groove, wound dehiscence, infection, skin necrosis, and lymphocele.1

A well-conducted operation should aim at avoiding any lymphatic, venous or arterial vessel impairment as well as any skin trauma, and result in limited or no skin tension. These goals are possible, and have been advocated and clearly demonstrated for many years.2–5

Preoperative Preparation

Good communication and avoidance of unreasonable expectations is essential, especially in those patients with large thighs.6 We classify our patients into four types:

Type I: The patient presents with isolated fat excess of the upper inner thigh. This should respond well to liposuction alone.

Type II: The patient shows a limited skin laxity.

Type III: The patient shows important skin laxity or excess, but limited to the upper third of the inner thigh. Type II and type III will require skin resection in a vertical manner, for a proper “lift” of the inner thigh.

Type IV: The patient has a skin laxity extending to the lower part of the inner thigh. Type IV patients will require additional skin resection, to tighten the thigh transversally, with a vertical scar extending gradually down to the knee according to the importance of the necessary resection.

Anatomical Considerations

Fat Layers

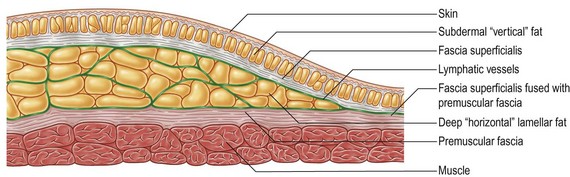

Fat distribution under the human skin is uneven (Fig. 34.1). There is an almost uniform superficial layer, where lobules are organized in a “vertical” manner, perpendicular to the skin surface. In these areas, the fascia superficialis is fused with the deep, premuscular fascia. In some areas, there is another layer, deep to the fascia superficialis, where the fat is organized in a “horizontal”, lamellar fashion, parallel to the skin surface. Liposuction allows for the elimination of most of the fat in the different layers, achieving not only volume reduction but also skin release. Skin retraction is best in those areas of deep fat, as retraction of the superficial, “vertical” fat layer often leads to surface irregularities.

Lymphatic Distribution

The lymphatic vessels of the skin (Fig. 34.1), after collecting from the surface, join into vessels situated just deep to the fascia superficialis. Therefore, in areas where there is deep fat, it is of the utmost importance that dissection stays superficial, in order to avoid any impairment of the lymphatic drainage. In some anatomical areas this boundary is not particularly obvious, for example in the outer thigh. Nevertheless, due to the frequently described lymphatic complications,7 dissection should stay superficial.

Skin Particularities

The skin of the upper inner thigh is very thin. Its blood supply will not tolerate excessive tension, which will subsequently lead to wound dehiscence or necrosis. Deep anchorage will prevent not only excessive tension on the suture line, but also secondary deformity, such as scar migration or vulvar dehiscence.8

Surgical Technique

Preparation and Positioning

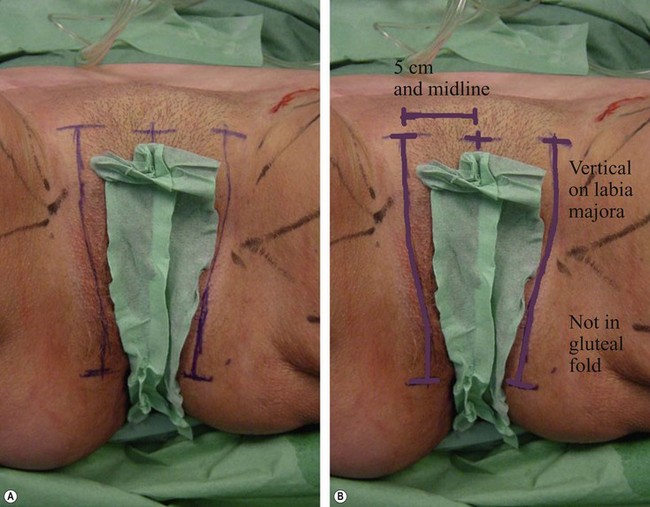

The incision line should avoid the inguinal crease, where there is a major risk of impairment of the lymphatics.2,9–11 Our incision is vertical within the pubis, starting from below the hairline, medial to the groin crease, 3 to 4 cm away from the midline on either side. Another reason for a pubic positioning is that superficial dissection in the groin region to preserve lymphatic vessels will result in a very thin skin flap, which will not tolerate any tension. The incision is then extended vertically toward the pubic tubercle along the labia majora. If the amount of skin resection is major, it seems preferable, as advocated by Le Louarn,11 to extend the marking of the incision to the inner part of the buttock toward the ischial tuberosity and the anal margin. This is a superior incision line as opposed to the gluteal fold, as this area is very prone to hypertrophic and painful scarring and is technically difficult to correct.

Skin Release

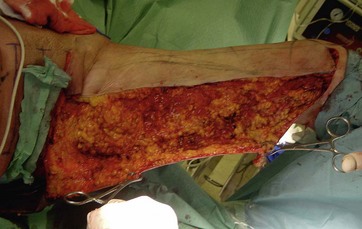

Extensive liposuction allows for a very thin skin flap (Fig. 34.3); the fascia superficialis is kept deep to undermining, preserving the lymphatic vessels’ integrity; skin elevation is limited to the planned resection.

Skin resection does not go beyond the elevated flap (Fig. 34.4); the risk of skin necrosis is reduced to a minimum.

FIG. 34.4 Skin resection does not go beyond elevated flap, risk of skin necrosis reduced to a minimum.

After infiltration with the following solution (1 liter saline, 40 ml of 1% lidocaine and 1 mg of epinephrine (adrenaline)), extensive liposuction will allow for volume reduction and associated skin tension release. This will effectively free the superficial dermal layers with preservation of deep fibrous and vascular attachments, as originally analysed in 1992 by Le Louarn5 and subsequently by Illouz.12 Surgical undermining becomes therefore unnecessary, apart from the zones to be removed; all fat there should be removed. The skin incision is superficial to the subcutaneous tissue. The margin is hooked and lifted, to undermine as superficial to the fascia superficialis as possible, as it is fairly easy to identify after removal of all fat. The excised skin is therefore extremely thin.

Skin Resection

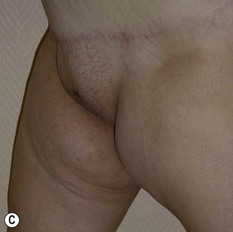

This point is anchored to Colles’s fascia with 2-0 Vicryl sutures. Two or three other anchoring points are then defined on either side, the superior flap being rotated medially towards the pubis with deep stitches grasping the deep fascia and the muscle insertion at the ischial tuberosity. The periosteum should be avoided, as this can be painful. Skin resection is performed step by step, only on the excess skin thus defined. Closure is achieved in two layers with 3-0 Vicryl sutures. No drainage is required, as there is no dead space. Figure 34.5 shows the closure of the incisions on the first side. Note, that despite the thigh position and vertical component, there is no deformation of the genital fold line. Note tension in the subgluteal fold; the scar will remain invisible posteriorly.

Optimizing Outcomes

Simple points to note are the following:

• Any surgical approach should stay superficial to the fascia superficialis, or premuscular fascia, whether perpendicular to the surface (skin incisions) or parallel to it (undermining), to preserve all lymphatic vessels.

• Undermining should be minimal in its extension so as to avoid impairment of blood supply.

• Tissue release should be maximal to allow for easy resection of excess skin and fat, and closure without tension.

• Deep anchorage with fixation to strong structures is mandatory.

• Incisions should be positioned in areas hidden and not prone to hypertrophic scarring.

Complications and Their Management

Lymphatic Drainage and Lymphocele

Some authors have advocated the risks of seroma or lymphocele formation associated with liposuction. In 1990 Ersek et al7 reported that liposuction associated with undermining in nine cases of abdominolipectomies led to seroma and pseudo bursa formation. This results in uneven skin retraction and unsightly aspect and he advocates waiting for 6 weeks after suction for resection. In 1995, Candiani et al9 operated on 18 patients for medial thigh lift with a full thickness undermining including the premuscular fascia, “cautious lipoaspiration when it was really necessary” and deep fasciofascial anchoring to Colles’s fascia. They observed three bilateral seromas requiring repeat aspirations. In their 2008 report on seroma development, Shermak et al13 found only 4% of seroma formation in thigh lifts. However, in 2009 Bruschi14 performed 11 liposuctions on 35 cases of thighplasty, and did not report any case of a lymphatic problem. In 25 cases, over a 2-year period, Le Louarn and Pascal in 2004,11 while preserving fascia superficialis, had no cases of lymphatic edema or seroma formation. In 2006, Espinosa-de-los-Monteros et al15 noted only two seromas in 60 cases of abdominoplasty with extensive liposuction, but preserving Scarpa’s fascia of the lower abdomen. Since introducing extensive liposuction, superficial dissection and no undermining, we have had no cases of lymphorrhea or lymphocele.

Clinical Cases

Case 1: Preoperative (Fig. 34.6A, B) and postoperative views (Fig. 34.6C, D) of the same patient, after bodylift and thighplasty with extensive circumferential liposuction of the thighs. A fair result.

Case 2: Preoperative (Fig. 34.7A–C) and postoperative views (Fig. 34.7D–F): in this early result, correction is satisfactory, but scar placement, due to extent of skin resection, could not allow for proper fixation on the deep planes, therefore allowing for downward scar migration. Nevertheless, no vulvar dehiscence occurred.

Case 3: Preoperative (Fig. 34.8A) and postoperative views (Fig. 34.8B): a very difficult condition. No indication for a vertical thigh approach, as the excess skin is limited to the upper third of the thigh. Extensive circumferential thigh liposuction should probably have been performed to allow for a better rotation of the anterior skin towards the pubis. No vulvar dehiscence despite the extreme vertical skin resection.

Case 4: Fig. 34.9A, B: a good result with the described technique, although today the vertical pubic scar would be slightly more medially placed.

1 Borud LJ, Cooper JS, Slavin SA. New management algorithm for lymphocele following medial thigh lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(4):1450–1455.

2 Shaer WD. Gluteal and thigh reduction: reclassification, critical review and improved technique for primary correction. Aesth Plast Surg. 1984;8:165–172.

3 Lockwood T. Superficial fascial system (SFS) of the trunk and extremities: a new concept. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(6):1009–1018.

4 Lockwood T. Lower body lift with superficial fascial system suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92(6):1112–1122.

5 Le Louarn C. Partial subfascial abdominoplasty: our technique apropos of 36 cases. Aesth Plast Surg. 1992;37:547–552.

6 Lewis CM. Dissatisfaction among women with “thunder thighs” undergoing closed aspirative lipoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg. 1987;11:187–191.

7 Ersek RA, Schade K. Subcutaneous pseudobursa secondary to suction and surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85:442–445.

8 Hodgkinson DJ. Medial thighplasty, prevention of scar migration, and labial flattening. Aesth Plast Surg. 1989;13:111–114.

9 Candiani P, Campiglio GL, Signorini M. Fascio-fascial suspension technique in medial thigh lifts. Aesth Plast Surg. 1995;19:137–140.

10 Spirito D. Medial thigh lift and D.E.C.L.I.V.E. Aesth Plast Surg. 1998;22:298–300.

11 Le Louarn C, Pascal JF. The concentric medial thigh lift. Aesth Plast Surg. 2004;28:20–23.

12 Illouz YG. A new safe and aesthetic approach to suction abdominoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg. 1992;16:237–245.

13 Shermak MA, Rotellini-Coltvet LA, Chand D. Seroma development following body contouring surgery for massive weight loss: patient risk factors and treatment strategies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(1):280–288.

14 Bruschi S, Datta G, Bocchiotti MA, et al. Limb contouring after massive weight loss: functional rather than aesthetic improvement. Obes Surg. 2009;19:407–411.

15 Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, De la Torre JI, Rosenberg LZ, et al. Abdominoplasty with total abdominal liposuction for patients with massive weight loss. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30:42–46.