12 Transplant surgery

Introduction and definitions

• Cadaveric donors who are brainstem dead are the commonest source of organs, often following severe head injury. The procedure for confirming brainstem death requires two senior doctors to perform a series of tests to establish the diagnosis (Box 12.1).

• Cadaveric non-heart-beating donors are occasionally used for renal transplants.

• Live donors may be related or non-related to the recipient. Living donors are usually first degree relatives of the recipient. Unrelated donors are rare in the developed world, though trading in organs occurs in poor countries.

• Autograft: transplantation of an organ from one part of the body to another part of the same individual.

• Isograft: transplantation of tissue between genetically identical individuals, i.e. identical twins.

• Allograft: transplantation of tissue from an individual of the same species. Most human organ transplants are allografts.

• Xenograft: transplantation of tissue from one species to another. This is limited to avascular tissues that have been treated to remove antigens. Porcine heart valves are examples of such grafts. Larger organs are rejected immediately. Using animal organs for human transplants would solve the organ shortage problem but there remain serious difficulties related to rejection and the potential for transfer of infectious diseases from the animal to human population.

• Orthoptic graft: the donor organ is transplanted to the same site after removal of the recipient’s diseased organ, e.g. liver transplantation.

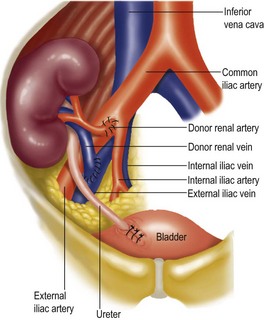

• Heterotopic graft: the organ is grafted to a site remote from the normal anatomic position, e.g. renal transplantation to the iliac fossa.

Box 12.1

Defining brain-stem death

3 Absent oculo-vestibular reflexes

4 No response to supraorbital pressure

5 No cough reflex or gagging response

6 No observed respiratory effort in response to disconnection of the ventilator (such that CO2 >6 kpa)

(from Academy of Medical Royal Colleges 2008 A Code of Practice for the Diagnosis and Confirmation of Death)

Rejection

• Hyperacute rejection is caused by preformed circulating antibodies present in the recipient’s blood which recognise antigens present on the cells of the donor organ. Rejection begins within hours and immediate loss of the graft ensues.

• Acute rejection is cell mediated and usually occurs 5–14 days after transplantation, though sometimes it may take several months.

• Chronic rejection involves cell- and antibody-mediated processes and causes graft ischaemia. Deterioration is slow and insidious but inevitably results in graft failure.

Matching donor to recipient

Tissue typing

The molecules that are involved in immune recognition are the major histocompatibility (MHC) antigens. Class I MHC antigens are expressed as integral proteins of the surface membranes of all nucleated cells and platelets. Class II MHC antigens are found on lymphocytes. The genes coding for the MHC proteins are located on the short arm of chromosome 6, termed the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) loci (Table 12.1). Tissue typing identifies which of the HLA-A, -B and -DR alleles are present for a donor or recipient.

Table 12.1 The four HLA loci and their importance in organ transplantation. Modern immunosuppressants have made HLA compatibility less critical

| HLA locus | Number of alleles identified/function |

|---|---|

| HLA-A | 20 alleles |

| HLA-B | 30 alleles (less importance for graft outcome) |

| HLA-C | No apparent role in immune response |

| HLA-DR | The most important: if donor and recipient match graft prognosis is better |

Immunosuppression

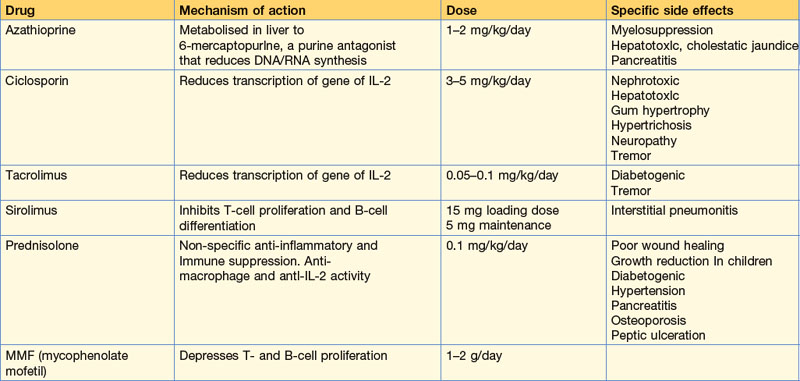

Immunosuppressive therapy prevents or reverses rejection of the transplanted organ but at the expense of increased risk of infectious and malignant disease (Box 12.2). Prophylaxis against rejection usually requires different agents to be used in combination. The main immunosuppressive agents, mechanisms of action, doses and side effects are summarised in Table 12.2. Acute rejection crises require high-dose intravenous steroids (methylprednisolone 500 mg three times a day) and occasionally monoclonal antibody therapy with basiliximab.

Organ retrieval and management of cadaveric organ donors

• maintain core temperature >35.5°C

• strict asepsis for ventilatory support; ensure adequate oxygenation and avoid high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) if possible

• adrenaline (epinephrine) is the best inotrope to support blood pressure

• treatment of diabetes insipidus (replace urine with 5% dextrose and desmopressin)

Kidney transplantation

Kidney transplantation is indicated for end-stage renal failure. The commonest causes are:

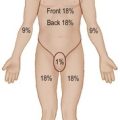

Ischaemic time comprises warm ischaemic time (between stopping the circulation through the organ and perfusing it with cold perfusion fluid) and cold ischaemia time, from the moment of cold perfusion to re-establishing blood flow after grafting. The shorter the ischaemia time, the sooner the graft will function after transplantation (Fig 12.1).

Liver transplantation

Indications for liver transplantation are summarised in Box 12.3. Outcome after transplantation for malignant disease is unpredictable and results are poor with high recurrence rates.

Pancreas transplantation

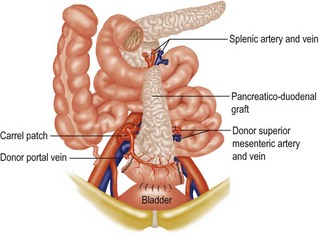

Pancreatic transplantation is indicated for insulin-dependent diabetes and may either be performed alone or together with renal transplantation for diabetics with advanced nephropathy. The operation is not widely performed in the UK though it is more popular in North America. There are two techniques: whole organ or segmental graft. The whole organ method has lower complication rates (Fig. 12.2). Results are improving but in the future it is likely that grafting of the pancreas will be replaced by transplantation of islet of Langerhans cells only.

Heart and lung transplantation

Heart, lung and heart-lung transplantation are discussed in Chapter 14.