Transperineal Repair of Rectal Prolapse

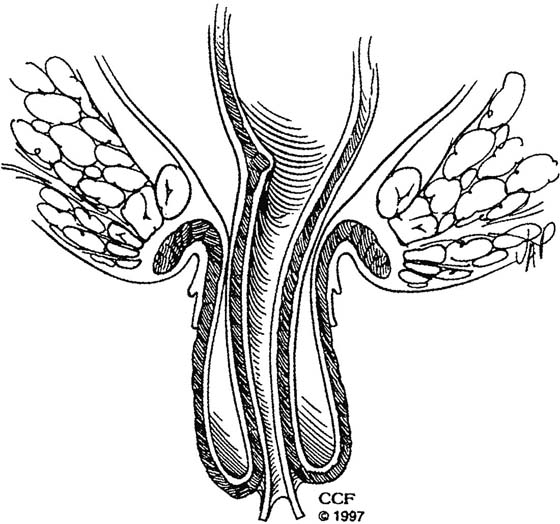

Rectal prolapse is characterized by a circumferential full-thickness protrusion of the rectum from the anus. It is believed to represent the culmination of a series of events leading to a sliding hernia through the levator hiatus (Fig. 101–1). This includes loss of sacral fixation, redundancy of the sigmoid colon and its mesentery, a deep anterior cul-de-sac, and a patulous anus. Treatments for rectal prolapse attempt to correct these problems and either restore the rectum to the pelvis or remove the hernia and redundant rectum. Although a number of options are available for the surgical correction of rectal prolapse, they can be broadly classified as transabdominal or transperineal.

Transabdominal repairs (laparoscopic or open) are better suited for most patients as they provide a more durable repair with a lower incidence of recurrence and improved functional outcomes when continence and overall bowel function are assessed.

This chapter addresses transperineal repairs, which are performed more often in elderly patients, who are poor candidates for general anesthesia or an abdominal incision. These patients tend to be older, to reside more frequently in nursing homes or assisted living, and to have a significantly greater number of comorbidities. In all transperineal approaches, the redundant rectum and any redundant sigmoid colon are resected, the cul-de-sac is obliterated, and the levators can be plicated posteriorly. The decision to perform a full-thickness resection (perineal proctectomy or the Altemeier procedure) or a partial-thickness resection (Delorme procedure) is based mainly on the surgeon’s preference, as these procedures seem to result in similar functional outcomes and recurrence rates.

Perineal Proctectomy (Altemeier Repair)

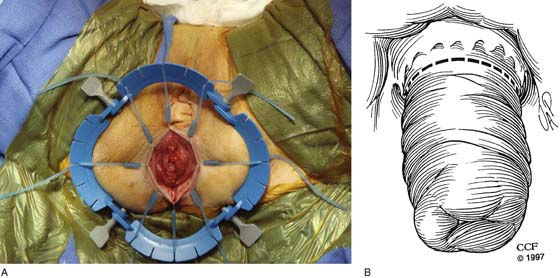

1. Spinal anesthesia is adequate for this procedure, but general anesthesia is acceptable if deemed safe. Most colorectal surgeons prefer to position the patient in a prone jackknife position under a spinal anesthesia with the buttocks taped apart. However, if the patient requires a vaginal procedure concomitantly, then a lithotomy position (Fig. 101–2) is preferred, so there is no need to reposition the patient. It is important to point out that in any type of combined procedure, the rectal prolapse should be addressed first, as it will be difficult to prolapse the rectum once the posterior colporrhaphy is performed.

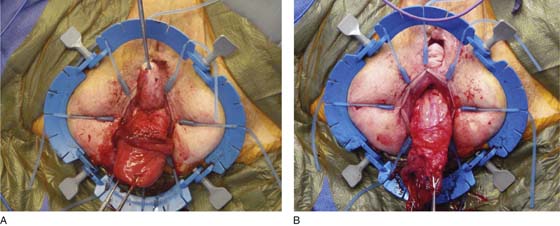

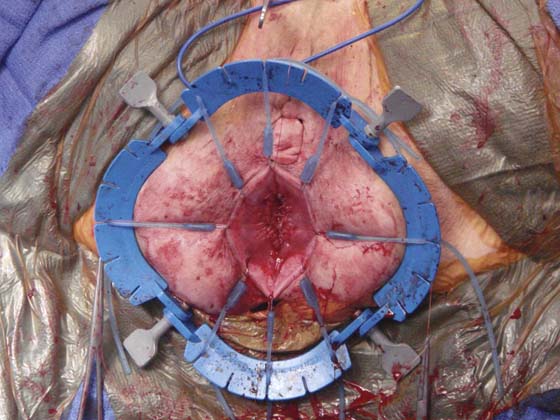

2. Once positioned, the rectum is prolapsed and a retractor is used to evert the anal canal (Fig. 101–3A, B), exposing the dentate line and the anal transition zone (zone between the rectal mucosa and the squamous mucosa of the anus). It is important to retain the transition zone, as it is important in discriminating gas from liquid and solid stool.

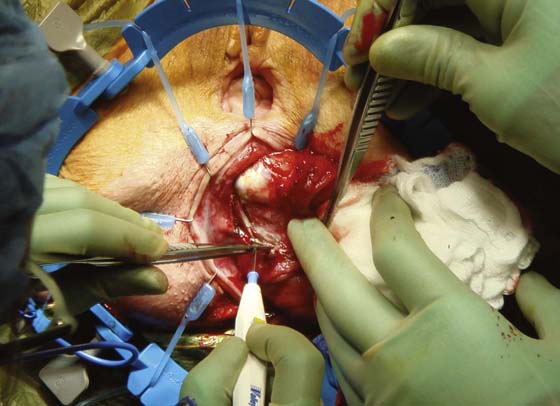

3. Electrocautery is then used to divide the rectal wall circumferentially (Fig. 101–4). With a finger in the rectum, folding of the rectal wall creates several layers, and the incision should be deep enough to expose the mesorectal fat on the inner tube of the rectum (Fig. 101–5).

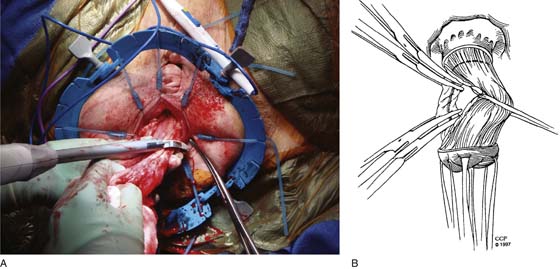

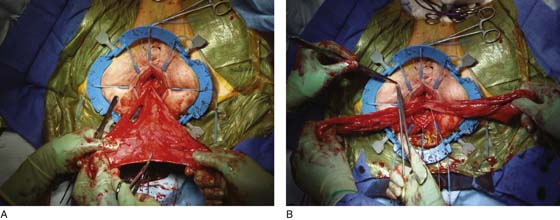

4. Between the anterior rectal wall and the vagina (Fig. 101–6A), the hernia sac or enterocele sac can be found and should be opened to facilitate lateral and posterior dissection (Fig. 101–6B).

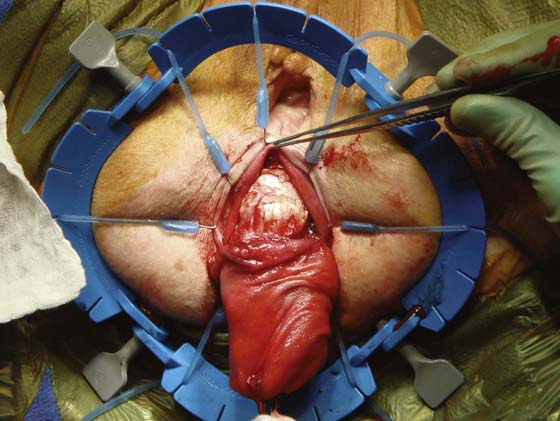

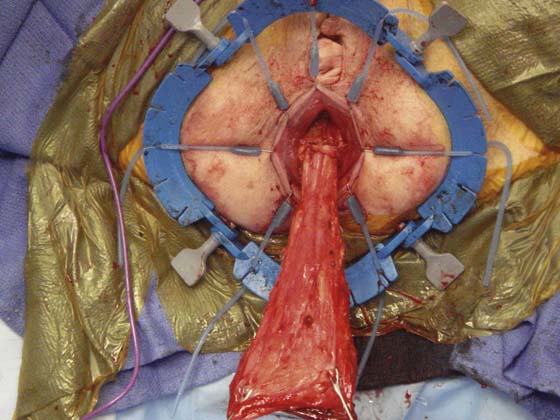

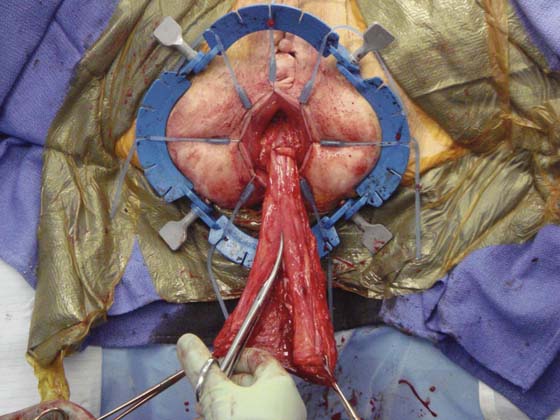

5. The author’s preference is to divide the mesorectum with a bipolar energy device (Fig. 101–7A), but it can be clamped and ligated just as effectively with heavy Vicryl ties (Fig. 101–7B). The dissection should be continued until there is no more laxity in the bowel, which now should be tethered only by the sigmoid or descending colon mesentery at the top of the sacral promontory (Fig. 101–8).

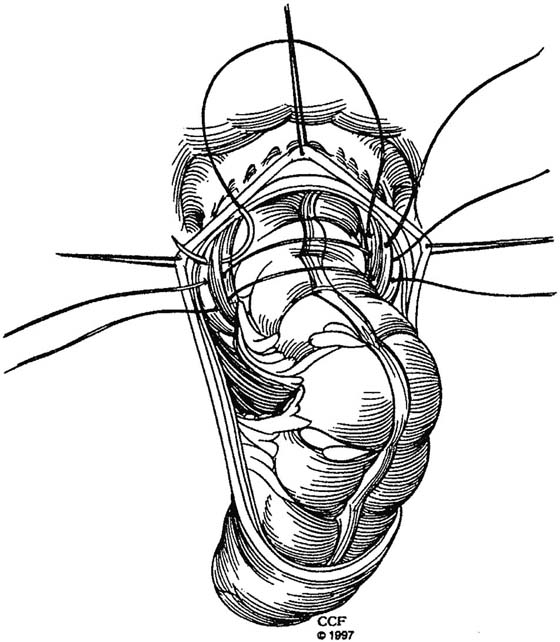

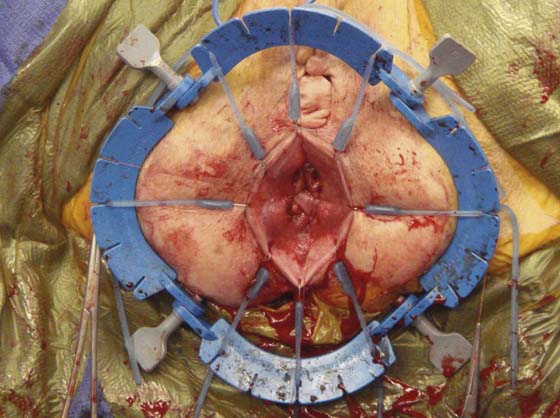

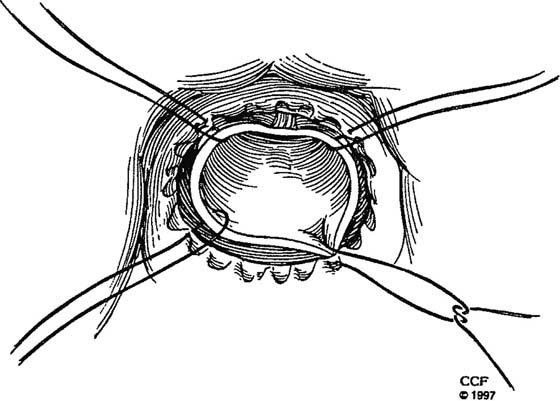

6. Before the anastomosis is conducted, a posterior levatorplasty can be performed (Fig. 101–9) in an effort to restore the anorectal angle, which is believed to be important in the overall continence of the patient.

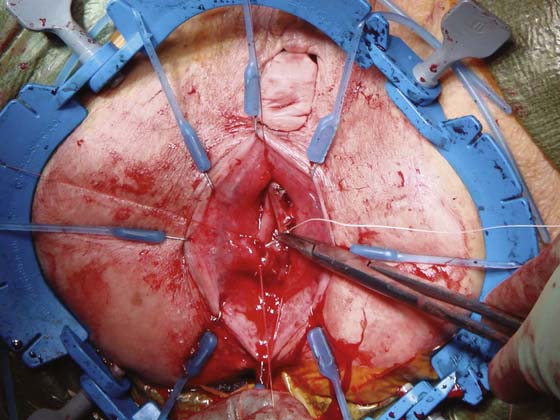

7. The redundant rectum is then resected (Figs. 101–10 and 101–11A, B) and sewn to the distal remnant with a series of interrupted 3-0 Vicryl sutures (Figs. 101–12 through 101–14).

8. Once completed, the anastomosis should be located at the top of the transition zone (Fig. 101–15), and the prolapse should be corrected (Fig. 101–16).

FIGURE 101–1 This illustrates the sliding hernia through the levators and sphincters, creating the full-thickness prolapse. Note the two distinct tubes with mucosa being exposed overlying the muscularis propria, which when divided will expose the outer layer of the inner tube (mesorectal fat).

FIGURE 101–2 The patient is in lithotomy with the rectum prolapsed. Note also the significant vaginal prolapse.

FIGURE 101–3 A. The Lone Star Retractor (CooperSurgical, Trumbull, CT) is very useful in everting the anus while exposing the rectal mucosa and the anal transition zone. The characteristic patulous anus of patients with prolapse is evident. B. The dotted line shows the point of transection.

FIGURE 101–4 The rectal wall is divided circumferentially by means of electrocautery. All layers of the rectal wall need to be divided if the prolapse is to be resected successfully.

FIGURE 101–5 This picture demonstrates the division of the muscularis propria of the rectal wall, exposing the underlying fat layer referred to as the mesorectum. This contains the lymphatics and the blood supply to the rectum and needs to be divided. Once through this layer, the muscularis propria of the inner tube will be exposed.

FIGURE 101–6 A. The vagina is prolapsed and is being lifted up off the anterior wall of the rectum. The enterocele or hernia sac will be found by continuing to dissect in this plane. If seen from an abdominal approach, this dissection would open the pouch of Douglas. B. Once the sac is opened, the rectum is delivered and the extraperitoneal rectum becomes evident.

FIGURE 101–7 To resect the redundant rectum, the mesorectum must be divided. This (A) can be done with an energy or bipolar device or (B) can be ligated between Kelly clamps and tied.

FIGURE 101–8 Once the rectal mesentery is fully divided, the prolapse becomes fully everted, exposing the top of the rectum and not infrequently the sigmoid colon. If there is still redundancy, the sigmoid mesentery can be divided at the sacral promontory. Great care must be taken when dividing the mesentery very proximally, as bleeding can be difficult to manage in the pelvis. Additionally, if the mesentery is taken too proximally, the colonic wall can become ischemic, resulting in an unsafe anastomosis.

FIGURE 101–9 Before performing the anastomosis, the levators can be plicated together using a nonabsorbable suture. This step can help restore the anorectal angle if placed posteriorly and reduce the size of the rectal hiatus. This may help to prevent recurrent prolapse. Care should be taken not to narrow the rectum, and at least one finger should be able to easily pass between the levators and the rectum.

FIGURE 101–10 The rectum is placed on stretch and the orientation is established so that there is no twisting. To maintain this orientation, the muscular tube is divided longitudinally along its anterior surface to the point where it will be cut off. The goal is to remove as much of the rectum or colon as is safe so that there is a good residual blood supply and the anastomosis is not under tension. A stitch is placed at the apex of the incision to the distal cuff of the transition zone.

FIGURE 101–11 A. The anterior stitch can be seen at the top of the picture, and a second longitudinal incision is made along the posterior aspect of the muscular tube. By approaching the anastomosis in this way, there is no risk of losing the proximal segment into the pelvis, and orientation is maintained. B. A second stitch is then placed posteriorly, much like the first stitch.

FIGURE 101–12 The two halves of the muscular tube are then resected circumferentially right and left, with stitches placed right lateral and left lateral.

FIGURE 101–13 Additional sutures are then placed in each quadrant. Two to three usually suffice. Often there is a size mismatch between the proximal colon and the rectal cuff, which can be dealt with by approaching the anastomosis through this stepwise approach.

FIGURE 101–14 The completed anastomosis should be tension-free and should show no evidence of ischemia. A gentle digital examination will reveal any defects remaining that can be repaired with additional sutures and will confirm a patent anastomosis.

FIGURE 101–15 Anastomosis is complete between the proximal colon and the transition zone (remnant rectal cuff). The transition zone allows for the discrimination of gas, liquid, and solid stool. Although this does not guarantee that the patient will be continent, most will experience improvement.

FIGURE 101–16 At the conclusion of the procedure, the rectal prolapse is no longer evident. One can see that there is little trauma to the anal margin skin and anoderm, which means that patients will have very little pain postoperatively—a key goal of this procedure.