Chapter 36 Transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty

1 INTRODUCTION

The ultimate goal of surgical treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is to improve symptoms and eliminate disease morbidity and mortality. This is accomplished by altering airway sizecompliance and shape. Successful surgery eliminates collapseairflow limitation and airway obstruction during sleep. The precise features of successful versus unsuccessful surgery remain poorly understood.

2 SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

2.1 EVALUATION

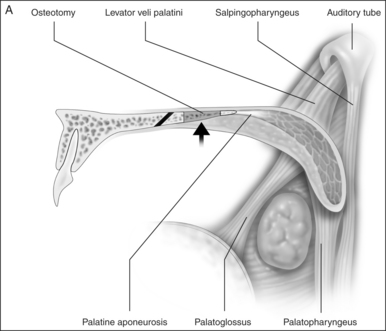

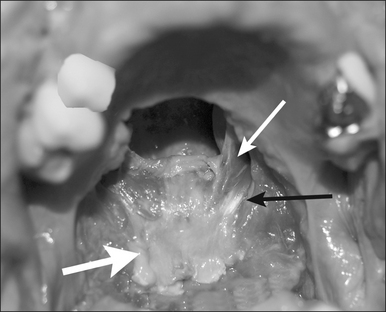

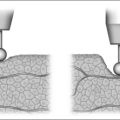

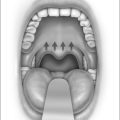

Preoperativelynasopharyngeal endoscopy is currently the primary method of airway evaluation and is performed in both a sitting and supine body position. Features evaluated include sizeshapeareas of collapseand pharyngeal swallow. During endoscopyclose attention is focused on the size and the shape of the proximal pharyngeal isthmus. Narrowing of the airway proximal to this point of estimated excision of traditional UPPP is an indication for primary transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty. The shape of the pharyngeal isthmus indicates whether narrowing is from anterior–posterior compression (transversely shaped) or from collapse of the lateral walls (sagittally shaped). The locations of the levator muscle and palatopharyngeal sphincter are identified by visualizing the anterior fold of the torus tubarus (torus levatorius) which leads to the position of the levator muscle in the soft palate (Fig. 36.1). A narrow anterior to posterior airway at this level indicates retromaxillary airway narrowing. Such an abnormality cannot be addressed by traditional palatopharyngoplasty without aggressive excision of the levator muscle.

Evaluation of the oropalatal airway is also needed. Since the palate relative to the tongue base is pulled forward a small oropalatal airway space may be worsened. This requires additional surgery even if the pharyngeal retroglossal airway space is not severely abnormal. The oropalatal airway is assessed initially with routine oral examination. A modified Malampatti 1 or 2 position indicates excellent oropalatal airway space. Modified Malampatti 3 and 4 have a compromised oropalatal airway. Those patients with very small oral airways who are primarily mouth breathers need this segment treated prior to palatal surgery.

2.2 THE PROCEDURE

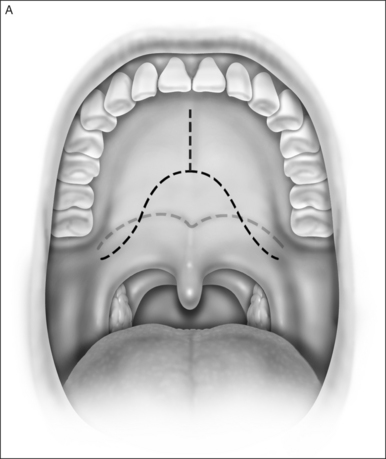

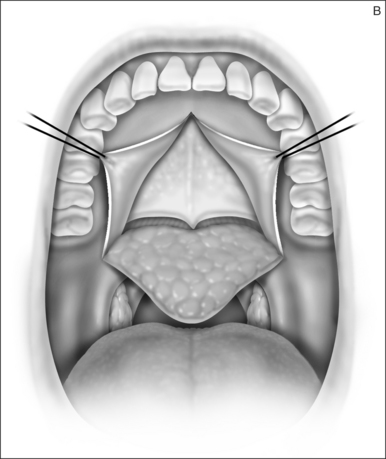

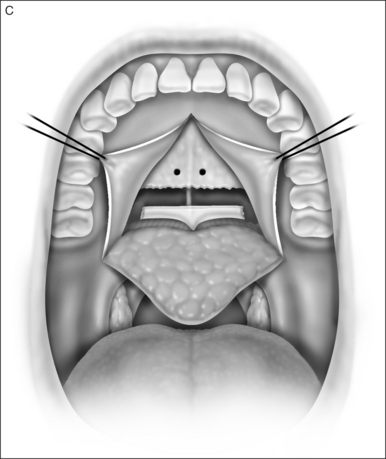

2.1.1 INCISIONFLAP ELEVATION

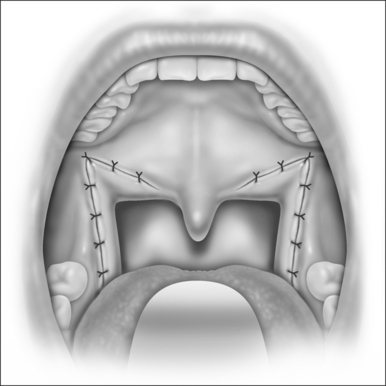

A palatal incision is outlined beginning at the central hard palate posterior to the alveolus. The anterior extent of the flap should extend approximately 5 mm anterior to the planned osteotomy. The incision is at the junction of the thinner palatal mucosa and the thicker fibroadipose and muscular layer (Fig. 36.1). The incision goes immediately medial to the greater palatine foramen and is then flared laterally at the junction of the hard and soft palate to extend laterally over the area of the hamulus. This results in a curvilinear ‘omega arch’ appearance. An additional incision extends vertically up the midline of the hard palate (‘T’ incision). This allows for laterally based flaps which allow for more lateral and anterior exposure of the hard palate and reduce the need for a longer midline flap which is at risk of tip necrosis.

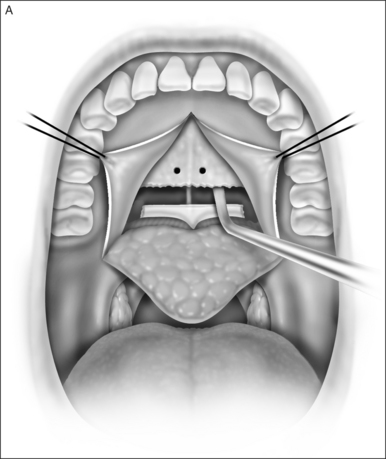

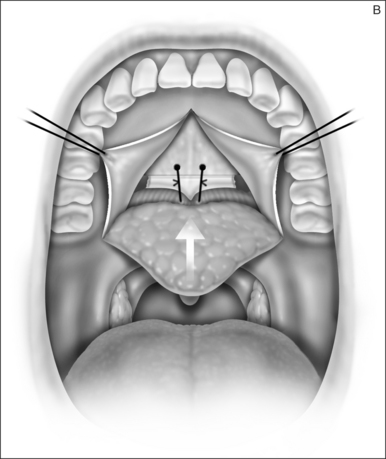

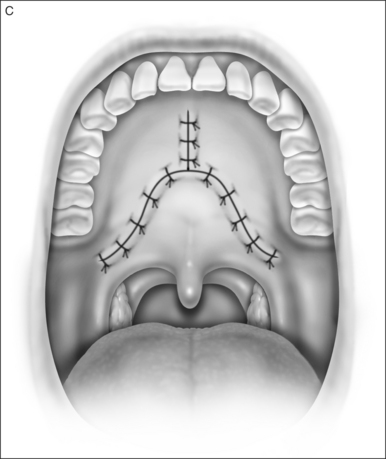

2.1.2 OSTEOTOMY, MOBILIZATION, TENDINOLYSIS, ADVANCEMENT AND CLOSURE

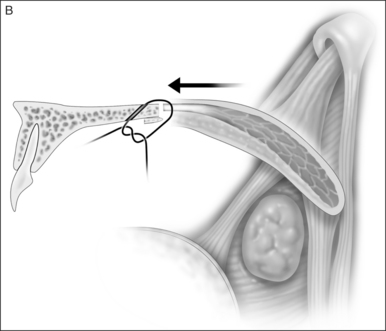

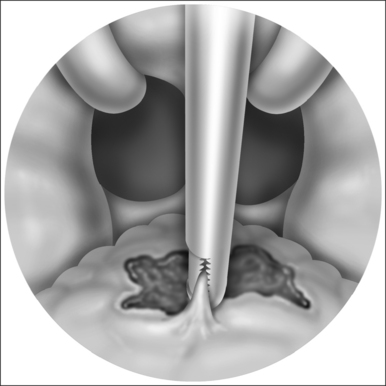

The soft palate must be mobilizedto allow palate advancement. The tensor tendon is incised laterally medial to the insertion on the hamulus. Tendonolysis includes both the tensor tendon and if needed fascial bands of the anterior belly of the levator palatini muscle (Fig. 36.4). Visual-izing the nasopharynx is important to identify the lateral nasopharyngeal walls and other landmarks and to avoid inadvertent dissection and trauma into the lateral wall of the nasopharynx. Nasal mucosa is incised (with electrocautery) proximal and lateral to the osteotomy. Fibroadipose tissue is dissected medial to the hamulus to identify the white fibers of the tensor tendon. These are in close proximity to the nasopharyngeal muscosa and tendonolysis is best approached from the dorsal (nasopharyngeal) surface. With sharp or judicious electrocautery dissectionthe tensor tendon is identified and cut.

2.1.3 DISTAL PALATOPHARYNGOPLASTY

In patients with an anatomically normal palate and uvulano surgery of the uvula and distal palate is required. In patients with redundant palatepillar mucosauvulaor tonsilsconservative surgery to tighten or remove this tissue may be needed with or without a tonsillectomy. In many patientspalatal advancement is performed after UPPP failure. In these or other cases pharyngeal stenosis may be present and scar release with conservative lateral pharyngoplasty or Z-plasty pharyngoplasty may be needed.

4 RESULTS

Early experience observed significant reductions in Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI) and Apnea Index (AI). A 67% successful response rate with a Respirators Disturbance Index (RDI) of less than 20 events/hour was observed in patients who only underwent transpalatal advancement.1–4 RDI in the responder group decreased from 52.8 to 12.3 events/hour. Seven of 11 patients (64%) had RDI reduced to less than 20 events/hour. Increased retropalatal size and decreased compliance have been observed. Photographic evaluation demonstrated increased velopharyngeal anterior posterior dimension and enlargement of the lateral pharyngeal ports.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty offers a potential alternative to aggressive UPPP in an attempt to enlarge the upper oropharyngeal airway and improve respiratory function. With this procedure the soft palate is mobilized not excisedand enlargement occurs with advancement. This advancement affects both the upper and lateral pharyngeal airway. Since palatal advancement alters only a portion of the airwaycomprehensive treatment is still required.

1. Zohar Y, Finkelstein Y, Strauss M, et al. Surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: comparison of techniques. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:1023-1029.

2. Ryan CF, Love LL. Unpredictable results of laser assisted uvulopalatoplasty in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax. 2000;55:399-404.

3. Blumen MB, Dahan S, Wagner I, et al. Radiofrequency versus LAUP for the treatment of snoring. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:67-73.

4. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 306 consecutively treated surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108:117-125.

Aboussouan et al. (1995) Aboussouan LS, Bolish JA, Wood BG, et al. Dynamic pharyngoscopy in predicting outcome of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for moderate and severe obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1995;107:941-946.

Caballero et al. (1998) Caballero P, Alvarez-Sala R, Garcia-Rio F. CT in the evaluation of the upper airway in healthy subjects and in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1998;113:111-116.

Friedman et al. (2002) Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Bass L. Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:13-21.

Fujita et al. (1998) Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, et al. Surgical correction of anatomic abnormalities of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:923-934.

Ikematsu et al. (1987) Ikematsu T. Palatopharyngoplasty and partial uvulectomy method of Ikematsu: a 30 year clinical study of snoring. In: Fairbanks DNL, Fujita S, Ikematsu T, Simmons FB, editors. Snoring and Sleep Apnea. 1st edn. New York: Rivlin Press; 1987:130-134.

Katsantonis et al. (1993) Katsantonis GP, Moss K, Miyazaki S, et al. Determining the site of airway collapse in obstructive sleep apnea with airway pressure monitoring. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:1126-1131.

Li et al. (2001) Li KK, Troell RJ, Riley RW, Powell NB, Koester U, Guilleminault C. Uvulopalatopharyngoplastymaxillomandibular advancementand the velopharynx. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1075-1078.

Morrison et al. (1993) Morrison DL, Launois SH, Isono S, et al. Pharyngeal narrowing and closing pressures in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:606-611.

Shepard et al. (1990) Shepard JW, Thawley SE. Localization of upper airway collapse during sleep in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:1350-1355.

Sher et al. (1996) Sher AE, Schechtman KB, Piccirillo JF. The efficacy of surgical modifications for the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996;19:156-177.

Skatvedt (1992) Skatvedt O. Continuous pressure measurements in the pharynx and esophagus during sleep in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:1275-1280.

Skatvedt et al. (1996) Skatvedt O, Akre H, Godtlibsen OB. Continuous pressure measurements in the evaluation of patients for laser assisted uvulopalatoplasty. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;253:390-394.

Woodson (1997) Woodson BT. Retropalatal airway characteristics in UPPP compared to transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:735-740.

Woodson (1999) Woodson BT. Acute effects of palatopharyngoplasty on airway collapsibility. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:82-86.

Woodson BT, Toohill RJ. Transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:269-276.

Woodson BT, Wooten MR. Manometric and endoscopic localization of airway obstruction after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:38-43.

Woodson B.T., Robinson S., Lim H.J. Transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty outcomes compared to uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:211-217.