Chapter 51 Transotic Approach

Despite well-documented technical details,1 there is a general misconception equating the transotic approach with the transcochlear approach of House and Hitselberger.2 Significant differences exist between the two approaches in the extent of exposure, the management of the facial nerve, and the obliteration of the surgical cavity. As a natural extension of subtotal petrosectomy, which forms the basis of lateral and posterior skull base surgery at the University of Zurich,1 the transotic approach was initially designed for acoustic neuromas and has since expanded to include other pathology. Several modifications were also made over the years to optimize its use.3–5

INDICATIONS

Acoustic Neuroma

At the University of Zurich, tumors larger than 2.5 cm that cause significant brainstem compression are managed by the neurosurgery department as a matter of departmental policy. Small intracanalicular tumors in patients with good hearing (using the 50/50 rule of at least 50 dB hearing loss and 50% discrimination score) are managed through a middle cranial fossa (transtemporal-supralabyrinthine) approach (see Chapter 35).

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

The evaluation for retrocochlear lesions, such as acoustic neuromas, is standard at the University of Zurich and includes routine audiometry, auditory brainstem response, electronystagmography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium enhancement. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) is still performed for bony assessment of lesions within or invading the temporal bone. Facial nerve status is recorded clinically using the Fisch grading system6 and quantified by electroneuronography before surgery.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Surgical Site Preparation, Positioning, and Draping

The positioning and draping for this procedure are similar to positioning and draping described in Chapter 1, with some minor differences. The patient is secured in supine position on the Fisch operating table (see Chapter 35), with the head turned away from the surgeon. A large plastic bag is incorporated into the draping to catch excess irrigation and blood.

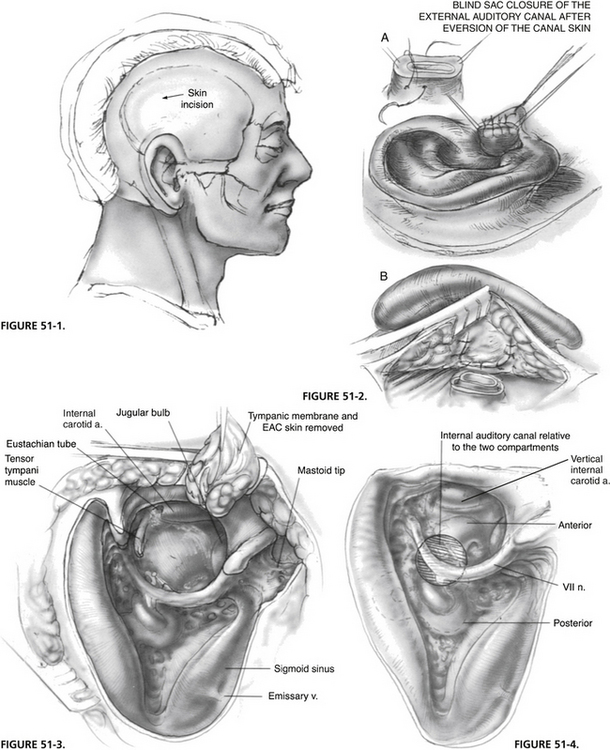

Skin Incision

A postauricular incision is placed along the hairline to keep it behind the operative cavity (Fig. 51-1). The incision is made from the mastoid tip to the temporal region for the surgical approach; its superior extension is made at the time of wound closure for the exposure of the temporalis muscle flap.

Blind Sac Closure of External Auditory Canal

A mastoid periosteal flap is developed while the postauricular skin flap is elevated. The external auditory canal is transected, and its skin is elevated, everted externally, and closed as a blind sac. A second layer of closure using the mastoid periosteal flap ensures a complete seal (Fig. 51-2).

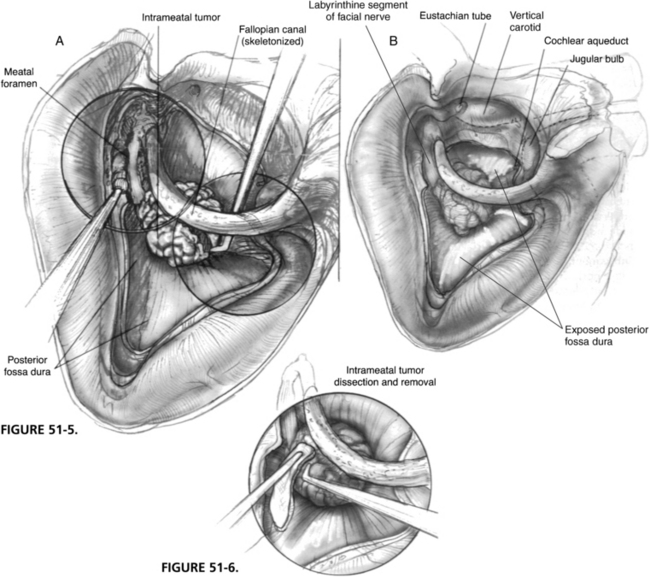

Subtotal Petrosectomy: Exposure of Jugular Bulb and Petrous Carotid

A complete mastoidectomy is performed, and the remaining external auditory canal skin, tympanic membrane, and ossicles are removed in a stepwise fashion. The tympanic bone is progressively thinned out, and a complete exenteration of the pneumatic spaces (retrofacial, retrolabyrinthine, supralabyrinthine, hypotympanic, infralabyrinthine, and pericarotid) is carried out. Figure 51-3 shows the surgical cavity at the completion of this step. The middle fossa dura, sigmoid sinus, and jugular bulb are blue-lined; the fallopian canal and the vertical portion of the petrous carotid artery are skeletonized. The mastoid tip is removed to reduce the depth of the surgical cavity.

Exenteration of Otic Capsule

With the completion of subtotal petrosectomy, the surgical cavity is divided into two compartments by the fallopian canal (Fig. 51-4). Because the enlarged IAC lies mostly deep within the anterior compartment, the advantage of the transotic approach to access this region fully is clear.

Unroofing of Labyrinthine Portion of Facial Nerve

The completed exposure is shown in Figure 51-5. The posterior fossa dura surrounding the porus is circumferentially exposed from the carotid artery to the sigmoid sinus, and from the jugular bulb to the level of the superior petrosal sinus.

Tumor Removal

A few instruments are required for tumor removal. Bayonet and angled bipolar forceps, cup forceps, microraspatories, and a long suction with finger control are the most essential instruments. The intrameatal portion of the tumor is approached first and is separated from the facial nerve until the level of the porus. Figure 51-6 illustrates the advantage of the additional space obtained with the transotic exenteration, whereby the intrameatal portion of the tumor can be easily displaced and mobilized during its removal.

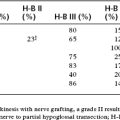

The posterior fossa dura is incised between the sinodural angle and the posterior edge of the porus. The incision is extended superiorly and inferiorly along the porus (Fig. 51-7). It is important to elevate the dura with a hook before making an incision to prevent the inadvertent injury of vessels over the cerebellum. The dural edges must be cauterized before extending the incision to facilitate hemostasis. One must also be acutely aware of the variations of the course of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) and its branches.

FIGURE 51-7 Dural incisions. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; PFD, posterior fossa dura.

FIGURE 51-9. Intracapsular tumor reduction.

FIGURE 51-10. Intracranial facial nerve dissection. AICA, anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

The superior and inferior dural flaps are retracted with 4-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) sutures, which are clipped to the wound edges (Fig. 51-8). The full extent of the tumor usually can be shown. The posterior pole of the tumor abuts against the cerebellum and the petrosal vein, and the AICA courses anteroinferior to the tumor.

Intracapsular reduction of the tumor can now begin and is continued until tumor margins can be seen without tension being placed on the facial nerve. During this step, the meatal dura at the superior pole of the porus is not detached to render some stability to the tumor. It is crucial to handle the tumor meticulously; manipulations should be carried out with suction over a Cottonoid, and the displaced facial nerve should always be in view to avoid undue traction (Fig. 51-9).

With sufficient reduction, separation of the facial nerve can now be attempted. The advantage of the transotic approach is now easily appreciated because the displaced facial nerve can be followed in its entirety. The dural attachments of the tumor at the porus are cut, and the nerve can be gently grasped with bipolar forceps and teased away from the tumor (Fig. 51-10). Likewise, the AICA can be separated from the nerve by using the tips of the forceps or by pulling on the coagulated branches.

At the inferior pole of the tumor, the origin of CN VIII and the course of the AICA looping around it are identified. In many instances, the root exit zone of the facial nerve, always anterior to CN VIII, is identified only after CN VIII is cut. The anterior access of the transotic approach offers an unparalleled view to an area that is usually partially hidden from the surgeon during suboccipital or translabyrinthine surgery.7,8 In this exact region, the facial nerve is most tenuous and frequently appears as a thin, transparent band. Any manipulation not under direct vision can easily rupture the nerve. When it is completely detached from all vital structures, the tumor can now be removed. The CPA and all its structures are exposed in Figure 51-11.

The facial nerve is stimulated electrically to obtain a threshold response. Despite a normal response intraoperatively, the patient may still show an immediate or delayed facial paralysis because of impaired vascular supply and the inevitable trauma to the nerve during dissection. If stimulation fails to produce a response or facial contraction, and if the anatomic integrity of the nerve is precarious, it is best to proceed with nerve grafting immediately. Failure to do so while waiting for the improbable return of facial function may delay reinnervation for 2 years. The details of intracranial/intratemporal and hypoglossal/facial crossover grafting techniques are beyond the scope of this chapter and are discussed elsewhere.1,9

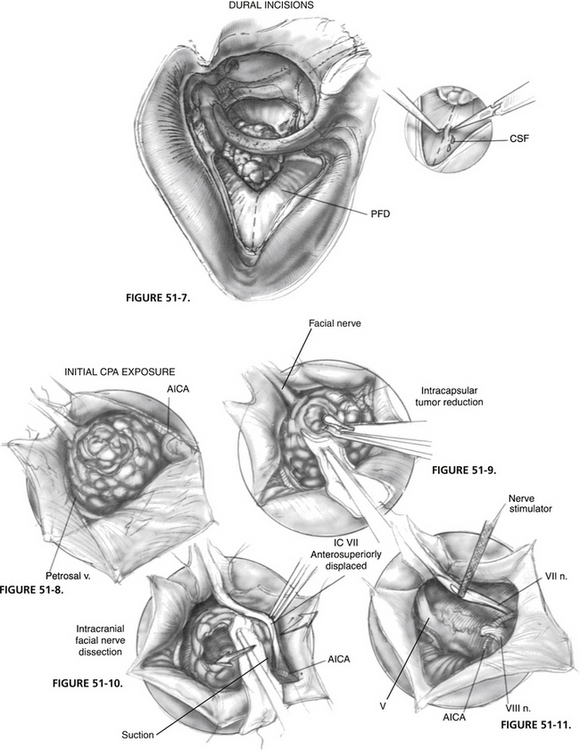

Wound Closure

A musculofascial graft that is slightly larger than the dural defect is taken from the temporalis muscle. It is placed under the dura and fixed in place with the two 4-0 Vicryl sutures used previously as stay sutures (Fig. 51-12). These sutures are passed through the edges of the graft and secured to the dura. A second temporalis fascial graft is used to cover the opened IAC. A small muscle graft is also used as a plug to supplement the prior wax obliteration of the eustachian tube. Both grafts are stabilized with fibrin glue.

FIGURE 51-12 Dural closure. IAM, internal auditory meatus.

FIGURE 51-13. Fat obliteration of surgical cavity.

FIGURE 51-14. Temporalis muscle flap. SCM, Sternocleidomastoid.

A second layer of closure with abdominal fat grafts is to follow. A large piece of fat is first passed under the fallopian canal and firmly anchored (Fig. 51-13). Several small pieces of fat are used to fill out the surgical cavity and are stabilized with fibrin glue.

The posterior half of the temporalis muscle is now transposed and sutured in place with 2-0 Vicryl sutures. Additional fat is placed under the muscle flap to create a slight compressive tension (Fig. 51-14). This type of closure has consistently minimized the incidence of postoperative CSF leaks, which is another advantage of the transotic approach. A small plastic suction drain is inserted over the muscle flap while the skin incision is closed in two layers with 2-0 polyglycolic acid (Dexon) and 3-0 nylon sutures.

TIPS AND PITFALLS

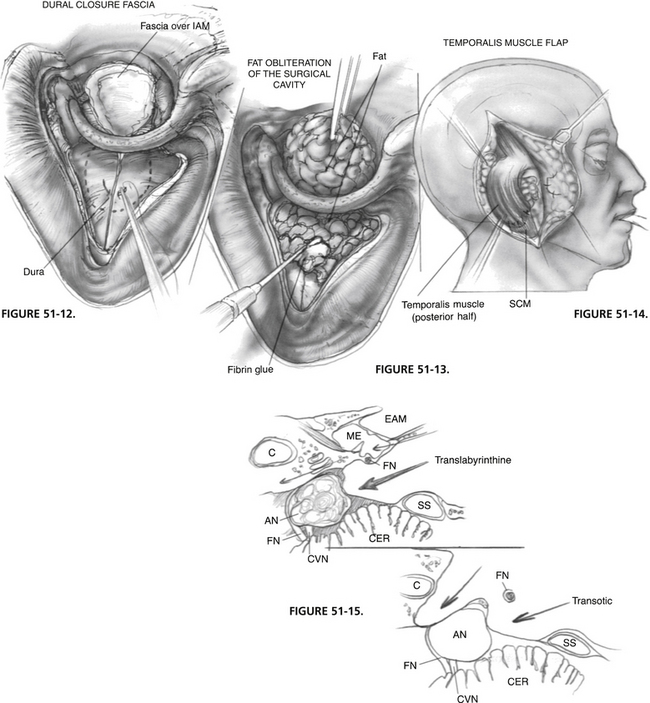

The transotic approach is more than a combination of the translabyrinthine and transcochlear approaches. It uses the complete infralabyrinthine compartment of the temporal bone, from the carotid artery to the sigmoid sinus, and from the jugular bulb to the superior petrosal sinus. It provides the largest possible transtemporal access to the CPA, which can be best appreciated by comparing the cross-sectional surgical exposure of the transotic approach with the translabyrinthine approach shown in Figure 51-15.

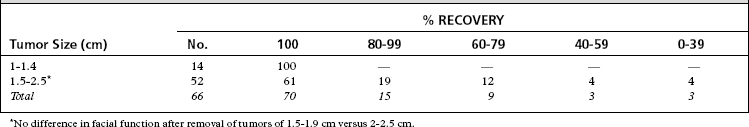

RESULTS

In this series, 66 patients were available for follow-up of at least 2 years. Tumors 1 to 1.4 cm were removed with no incidence of permanent facial injury, and 80% of patients with tumors 1.5 to 2.5 cm had normal or near-normal facial function (Table 51-1). Since 1988, the unroofing of the labyrinthine portion of the facial nerve has been a standard step in the transotic approach, which is believed to be a major contributing factor in the diminished incidence of delayed facial palsy in acoustic neuroma surgery.

ALTERNATIVE TECHNIQUES

Translabyrinthine and suboccipital approaches are perhaps the most established and popular techniques, whereas the middle fossa approach has traditionally been reserved for small tumors in patients with serviceable hearing; an extended version of the middle fossa approach has gained popularity in some centers to remove tumors measuring 4.5 cm10,11 despite a seemingly high morbidity.12 The relative efficacy of each of these approaches is difficult to quantify without a randomized multi-institutional study.

Our own experience with the translabyrinthine removal of acoustic neuromas before 1979 was unsatisfactory in many respects, and the problems were subsequently rectified with the transotic approach.1 There are three advantages of the transotic approach over the translabyrinthine approach, as follows:

1. Fisch U., Mattox D. Microsurgery of the Skull Base. New York: Thieme Publishers; 1988.

2. House W.F., Hitselberger W.E. The transcochlear approach to the skull base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1976;102:334-342.

3. Jenkins H.A., Fisch U. The transotic approach to resection of difficult acoustic tumors of the cerebellopontine angle. Am J Otol. 1980;2:70-76.

4. Gantz B.J., Fisch U. Modified transotic approach to the cerebellopontine angle. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1983;109:252-256.

5. Chen J.M., Fisch U. The transotic approach in acoustic neuroma surgery. J Otolaryngol. 1993;22:331-336.

6. Burres S., Fisch U. The comparison of facial grading systems. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;112:755-758.

7. Whittaker C.K., Leutje C.M. Translabyrinthine removal of large acoustic neuromas. Am J Otol. 1985;7(Suppl):155-160.

8. Gardner G., Robertson J.H. Transtemporal approaches to the cranial cavity. Am J Otol. 1985;7(Suppl):114-120.

9. Fisch U., Lanser M.J. Facial nerve grafting. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1991;24:691-708.

10. Wigand M.E., Haid T. Extended middle cranial fossa approach for acoustic neuroma surgery. Skull Base Surg. 1991;1:183-187.

11. Kanzaki J., Ogawa K., Yamamoto M., et al. Results of acoustic neuroma surgery by the extended middle cranial fossa approach. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl (Stockh). 1991;487:17-21.

12. Kanzaki J., Ogawa K., Tsuchihashi N., et al. Postoperative complications in acoustic neuroma surgery by the extended middle cranial fossa approach. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl (Stockh). 1991;487:75-79.