CHAPTER 73 Transnasal Esophagoscopy

History

The work of many pioneers has enabled the modern physician to visualize and study the esophagus.1 Bozzini, in 1806, was the first physician to report the ability to visualize the proximal esophagus.2 After studying the performances of sword swallowers, Kussmaul performed the first rigid esophagoscopy in 1868. Advances in equipment continued to be made through the work of physicians such as Von Mikulicz (1881, first electrically lighted esophagoscope), Einhorn (1897, distal illumination in an esophagoscope), and Jackson (advances in endoscopic instruments). Interestingly, Jackson did not use anesthesia, general or local, for esophagoscopy of adults.

While advances in equipment, lighting, and optics were being made in rigid instrumentation, a major advance toward flexible esophagoscopy was made through the work of Hirschowitz and associates,3 who presented the first fiberoptic gastroscope in 1957. Since that time, the examination of the esophagus has been conducted primarily by gastroenterologists with flexible endoscopes and patient sedation. Shaker,4 a gastroenterologist, published the first report of unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in 1994. Although initially met with limited interest from gastroenterologists, the appeal of unsedated transnasal esophagoscopy (TNE) grew among the otolaryngology community, particularly after the reports of Herrmann and Recio5 and the live demonstration by Aviv and colleagues6 in 2001.

Equipment

Two main camera systems exist for TNE. The proximal “add-on” camera is familiar to most otolaryngologists who perform endoscopy. Endoscopes utilizing this tool typically lack a working channel and require an add-on sheath. Alternatively, distal videochip technology has emerged, whereby optical impulses are converted to electric signals without the need for optical fibers.7 A separate video processor is required for visualization in this system (Fig. 73-1).

Tolerance of Unsedated Examination

Historically, examination of the esophagus has been performed with patient sedation. Analyses of the complication patterns during endoscopy reveal that most adverse events are related to sedation. Cardiopulmonary complications account for more than 50% of all reported complications, with the majority being due to aspiration, over-sedation, hypoventilation, vasovagal episodes, and airway obstruction.8 A 2007 national survey of endoscopists confirmed that unplanned cardiopulmonary events secondary to conscious sedation constitute the majority of endoscopy complications—67% of complications and 72% of mortalities were cardiopulmonary related.9

In addition to the medical risks of sedation, economic factors arise. The increased direct costs of conventional esophagoscopy include a longer procedure time, longer recovery time, and the costs associated with the needed medications, sedation, and recovery teams.10 Unsedated TNE has been found to be up to two thirds less expensive than conventional esophagoscopy.11,12 Indirect costs accrued with conventional esophagoscopy include the loss of work time for both the patient and an adult for patient transportation. In contrast, with an unsedated examination, patients are able to resume routine daily activities shortly after completion of the study.

Physiologic studies have verified that unsedated esophagoscopy is a safe procedure. In a prospective study, the changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressures, pulse rate, and rate-pressure product, as well as the drop in arterial oxygen saturation experienced by patients who had conventional transoral EGD, were significantly greater than in those undergoing either transnasal or transoral small endoscopy. Between the two small endoscope groups, these same parameters had a significantly greater change in the transoral group than in the transnasal group at 2 minutes after esophageal intubation.13 Additional studies have shown that a significant increase in heart rate and a significant decrease in oxygen saturation occur in those undergoing transoral esophagoscopy but not in those undergoing transnasal esophagoscopy.14

Although initial patient anxiety is higher before unsedated TNE, numerous studies have demonstrated a very high patient satisfaction rate, usually greater than that for conventional or transoral approaches.15–18 Crossover studies have shown that in patients who have undergone both sedated and unsedated endoscopy, the unsedated examination was better tolerated.19 Dumortier and coworkers20 found that 91% of patients who had undergone unsedated TNE who had also previously had a conventional EGD stated that they preferred the TNE examination. TNE was associated with fewer gagging sensations and was rated with higher patient satisfaction than unsedated transoral examinations.21–23

Accuracy of Examination

Dean and associates24 reported a high degree of correlation between the endoscopic findings (sensitivity 89%, specificity 97%) of TNE examinations and of conventional EGD. Although the biopsy sample size obtained with TNE is generally smaller than that obtained with conventional endoscopy, numerous studies have verified the accuracy of TNE-guided biopsies. In patients with known Barrett’s metaplasia, Saeian and colleagues25 found that the congruence between biopsy samples obtained with conventional endoscopy and those obtained with TNE was 97%. In a crossover study of 121 patients, Jobe and colleagues26 compared the endoscopic findings and the histologic detection of Barrett’s esophagus from biopsy specimens obtained from unsedated TNE and conventional esophagoscopy. A moderate to very good extent of agreement was present for endoscopic findings, such as hiatal hernias and esophagitis, between the two endoscopic modalities. In addition, although the biopsy specimen size was significantly smaller with TNE, there was a moderate extent of agreement in pathologic findings.26

Technique

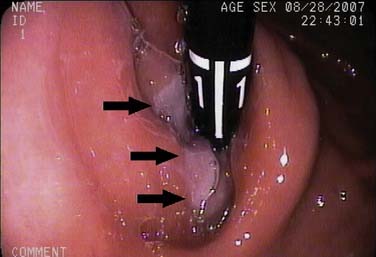

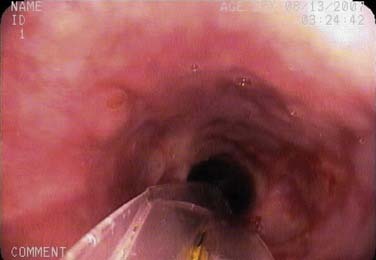

The endoscope is advanced into the distal esophagus for visualization of the gastroesophageal junction and the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ), also known as the Z-line. The endoscope is advanced more deeply into the stomach and retroflexed to visualize the gastric cardia. The mucosa of the entire esophagus is examined while the instrument is withdrawn. The post-cricoid region is visualized by insufflation of a burst of air as the endoscope is withdrawn from the esophagus (Fig. 73-2).15

Normal Findings

The anatomy of the esophagus viewed through a thin endoscope appears different from that obtained through a rigid esophagoscope or a conventional oral esophagoscope.27 By nature of the smaller size of the scope, TNE does not distort the anatomy of the esophagus, thereby allowing the natural curvatures and external compressions to be easily seen.

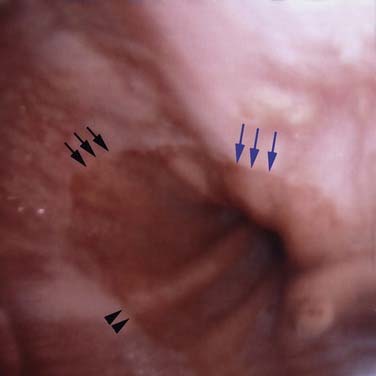

Esophageal squamous epithelium normally appears as a gray-white color, whereas the gastric columnar epithelium is of a salmon-pink hue. The SCJ occurs at the meeting of the esophageal mucosa and gastric mucosa. An irregularly shaped SCJ may be found and is not always pathologic. The junction of the gastric rugae and the network of terminal linear vessels marks the level of the gastroesophageal junction. The SCJ and the junction should normally coincide. However, finding the SCJ above the gastroesophageal junction represents clinical Barrett’s esophagitis (Figs. 73-3 and 73-4).

Indications

The rate at which pathology is found on TNE performed in an otolaryngology practice is high, approaching 50%.15,28 Indications for TNE can be divided into three major categories: esophageal, extraesophageal, and procedure-related. Esophageal indications include dysphagia, refractory or long-standing gastroesophageal reflux, abnormal radiographic study, and screening for Barrett’s metaplasia. Extraesophageal indications include globus pharyngeus, head and neck cancer, laryngopharyngeal reflux, and chronic cough. Reavis and colleagues29 found that patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma exhibited extraesophageal reflux symptoms more frequently than typical gastroesophageal reflux complaints, with chronic cough being the most common single complaint.29 Procedures for which TNE may be used are detailed in the following sections.

Transnasal Esophagoscopy in Head and Neck Oncology

Panendoscopy is considered part of the standard evaluation of patients diagnosed with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Often, these patients possess comorbidities that increase the risks of general anesthesia. Unsedated office TNE allows for an examination of the aerodigestive tract without the morbidity of anesthesia. A complete examination can be performed in a high percentage of patients, with series reporting up to 99%.30 Biopsy specimens can also be obtained on the day of the in-office endoscopy. In patients with presumed head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, a high degree of congruence has been shown between specimens obtained through TNE and those obtained from standard operating room panendoscopy.31

Patients requiring extensive resection of a head and neck malignancy may need complex reconstruction, including the use of free tissue flaps. TNE may be used for surveillance of the reconstruction and to check the integrity of the flap both in the immediate postoperative period and during further follow-up examinations.32

Transnasal Esophagoscopy in Barrett’s Esophagus

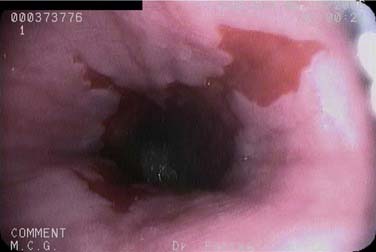

Although most cancers in the United States are showing a decline in prevalence, the rate of esophageal adenocarcinoma is on the rise. Barrett’s esophagus represents a premalignant state for this type of esophageal neoplasm. TNE is a useful screening examination for this condition. Limitations of TNE include the inability to use jumbo forceps or comfortably to obtain a full four-quadrant range of biopsy specimens spaced every 1 to 2 cm, which are standard during conventional Barrett’s esophagus surveillance. Therefore, TNE is not currently recommended for the surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus (Fig. 73-5).

Transnasal Esophagoscopy in Dysphagia

Dysphagia is a growing clinical concern, particularly among the elderly. TNE complements other diagnostic tools, including manometry, flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow (FEES), flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing with sensory testing (FEESST), and radiographic studies such as the barium esophagram and the modified barium swallow. Unlike these other studies, TNE allows direct visual inspection of the mucosa. An additional advantage of this unsedated examination is the ability to subjectively assess peristaltic activity. A pill, food, or a liquid can be swallowed and observed to travel through the esophagus, in order to localize areas of decreased peristalsis or narrowing. Transit time for a liquid is usually less than 13 seconds. Conditions found during TNE for dysphagia include esophagitis, strictures, rings, large hiatal hernias, webs, primary or metastatic neoplasms, eosinophilic esophagitis, vascular anomalies, and diverticula. A tight lower esophageal stricture found on endoscopy can also suggest the diagnosis of achalasia rather than the presence of a tumor (pseudoachalasia) (Fig. 73-6).

Additional Diagnostic Applications of Transnasal Esophagoscopy

New indications for TNE are continually being developed. Among its novel applications are documenting the resolution of Helicobacter pylori infection and the detection and grading of esophageal varices.33 The ability to evaluate esophageal pathology without sedation is particularly valuable in patients with cirrhosis in order to avoid the risk of postsedation encephalopathy.34 Similarly, serial evaluations after a caustic ingestion can be accomplished with TNE without the need for repeated anesthesia. Foreign bodies, such as impacted food, may be diagnosed with TNE and “pushed” into the stomach. It is our opinion that unsedated TNE should not be used for the removal of foreign bodies because of airway concerns. Finally, technologic innovations, such as narrow-band imaging, may further improve the diagnostic accuracy of TNE.35

Procedures

Stricture Dilation

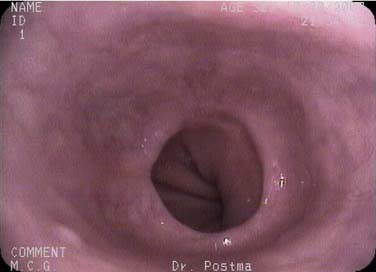

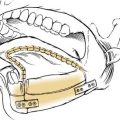

When patients complain of a primarily solid rather than liquid dysphagia, an anatomic etiology is often present, such as a stricture or web. Traditionally, the treatment of esophageal strictures involves mechanical dilation, often with bougies, in the operating room or with sedated endoscopy. Patients may need multiple treatment sessions. The need for numerous anesthetics and “blind” dilation is avoided with the use of unsedated TNE.36 Controlled radial expansion (CRE) balloons can be passed over a guidewire to dilate narrowed segments.37,38 Evidence suggests that these balloons may be less traumatic than bougies.39 Unsedated TNE has been used to successfully dilate esophageal strictures in conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa as well as those induced by reflux or radiation.40,41 The endoscope can also guide placement of controlled radial expansion balloons to treat radiation-induced stenosis of the nasopharynx. Neopharyngeal strictures that may occur after total laryngectomy have been successfully dilated with the use of office unsedated TNE as well (Fig. 73-7).42

Tracheoesophageal Puncture

Tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP) is one of the most commonly used vocal rehabilitation pathways following total laryngectomy.43 TNE can be used for secondary TEP placement. Traditionally, secondary TEP placement is performed with general anesthesia and a rigid esophagoscope. In addition to the risks associated with general anesthesia, this technique can be complicated by difficulty passing the rigid esophagoscope in patients lacking neck flexion or passing the instrument through friable tissue.44

The procedure begins with the endoscope’s being passed into the neopharynx. A needle is then passed through the posterior tracheal wall and through the anterior wall of the esophagus, which is observed under direct visualization. Air is insufflated into the neopharynx to promote visualization and protect the posterior esophageal wall from accidental needle penetration. The incision is enlarged and then either a catheter or the TEP prosthesis itself may be inserted. A study found that in-office, unsedated secondary TEP placement was successful in 10 of 11 patients.45 TNE can also be used to diagnose and replace a TEP device that has failed because of malposition.46

Additional Therapeutic Applications of Transnasal Esophagoscopy

Laser fibers can be passed through the working channel for ablation of esophageal papillomas or other small tumors. Unsedated TNE has also been used successfully to position wireless telemetry devices in the esophagus for pH monitoring.47

Complications

One of the most feared complications of esophagoscopy is esophageal perforation. Among the thousands of cases performed, only one case of esophageal perforation has been reported, when unsedated TNE was performed by a gastroenterologist.16 There have been no reported cases of esophageal perforation during TNE performed by an otolaryngologist. Minor complications have been reported. In two of the largest series reported, involving 700 patients from the United States and 1100 patients from France, rates of epistaxis were reported between 0.85% and 2% and those of vasovagal events to be 0.3%.15,20 Mild, self-resolving nasal discomfort was reported at 1.6%.

Andrus JG, Dolan RW, Anderson TD. Transnasal esophagoscopy: a high-yield diagnostic tool. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:993-996.

Aviv JE, Takoudes TG, Ma G, et al. Office-based esophagoscopy: a preliminary report. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:170-175.

Doctor VS, Enepekides DJ, Farwell DG, et al. Transnasal oesophagoscopy-guided in-office secondary tracheoesophageal puncture. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122(3):303-306.

Dumortier J, Napoleon B, Hedelius F, et al. Unsedated transnasal EGD in daily practice: results with 1100 consecutive patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:198-204.

Garcia RT, Cello JP, Nguyen MH, et al. Office-based unsedated small-caliber endoscopy is equivalent to conventional sedated endoscopy in screening and surveillance for Barrett’s esophagus: a randomized and blinded comparison. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2693-2703.

Marsh BR. Historic development of bronchoesophagology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:689-716.

Postma GN, Bach KK, Belafsky PC, et al. The role of transnasal esophagoscopy in head and neck oncology. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:2242-2243.

Postma GN, Belafsky PC, Aviv JE. Atlas of Transnasal Esophagoscopy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

Postma GN, Cohen JT, Belafsky PC, et al. Transnasal esophagoscopy: revisited (over 700 consecutive cases). Laryngoscope. 2005;115:321-323.

Reavis KM, Morris CD, Gopal DV, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms better predict the presence of esophageal adenocarcinoma than typical gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Ann Surg. 2004;239:849-856.

Saeian K, Staff DM, Vasilopoulos S, et al. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy accurately detects Barrett’s metaplasia and dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:472-478.

Schlueck G, McQuaid KR. Unsedated ultrathin EGD is well accepted when compared with conventional sedated EGD: a multicenter randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1606-1612.

Shaker R. Unsedated transnasal pharyngoesophagogastroduodenoscopy (t-EGD). Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:346-348.

Thota PN, Zuccaro G, Vargo JJ, et al. A randomized prospective trial comparing unsedated esophagoscopy via transnasal and transoral routes using a 4-mm video endoscope with conventional endoscopy with sedation. Endoscopy. 2005;37:559-565.

Waring JP, Baron TH, Hirota WK, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Standards of Practice Committee. Guidelines for conscious sedation and monitoring during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:317-322.

Yagi J, Adachi K, Arima N, et al. A prospective randomized comparative study on the safety and tolerability of transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1226-1231.

1. Marsh BR. Historic development of bronchoesophagology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:689-716.

2. Bush RB, Leonhardt H, Bush IM, et al. Bozzini’s lichtleiter: a translation of his original article (1806). Urology. 1974;3:119-123.

3. Hirschowitz BL, Curtiss LE, Peters CW, et al. Demonstration of a new gastroscope “the fiberscope”. Gastroenterology. 1958;35:50-53.

4. Shaker R. Unsedated transnasal pharyngoesophagogastroduodenoscopy (t-EGD). Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:346-348.

5. Herrmann IF, Recio SA. Functional pharyngoesophagoscopy: a new technique for diagnostics and analyzing deglutition. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;8:163-167.

6. Aviv JE, Takoudes TG, Ma G, et al. Office-based esophagoscopy: a preliminary report. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:170-175.

7. Lux G, Knyrim K, Scheubel R, et al. Electronic endoscopy—fibres or chips? Z Gastroenterol. 1986;24:337-343.

8. Waring JP, Baron TH, Hirota WK, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Standards of Practice Committee. Guidelines for conscious sedation and monitoring during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:317-322.

9. Sharma VK, Nguyen CC, Crowell MD, et al. A national study of cardiopulmonary unplanned events after GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:27-34.

10. Garcia RT, Cello JP, Nguyen MH, et al. Unsedated ultrathin EGD is well accepted when compared with conventional sedated EGD: a multicenter randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1606-1612.

11. Watts TL, Shahidzadeh R, Chaudhary A, et al. Cost savings of unsedated transnasal esophagoscopy. Paper presented at: 87th Annual Meeting of the American Broncho-Esophageal Association; April 26-27, 2007; San Diego, CA.

12. Gorelick AB, Inadomi JM, Barnett JL. Unsedated small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): less expensive and less time-consuming than conventional EGD. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:210-214.

13. Yagi J, Adachi K, Arima N, et al. A prospective randomized comparative study on the safety and tolerability of transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1226-1231.

14. Kawai T, Miyazaki I, Yagi K, et al. Comparison of the effects on cardiopulmonary function of ultrathin transnasal versus normal diameter transoral esophagogastroduodenoscopy in Japan. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:770-774.

15. Postma GN, Cohen JT, Belafsky PC, et al. Transnasal esophagoscopy: revisited (over 700 consecutive cases). Laryngoscope. 2005;115:321-323.

16. Zaman A, Hahn M, Hapke R, et al. A randomized trial of peroral versus transnasal unsedated endoscopy using an ultrathin videoendoscope. Gastroinest Endosc. 1999;49:279-284.

17. Garcia RT, Cello JP, Nguyen MH, et al. Unsedated ultrathin EGD is well accepted when compared with conventional sedated EGD: a multicenter randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1606-1612.

18. Mulcahy HE, Riches A, Kiely M, et al. A prospective controlled trial of an ultrathin versus a conventional endoscope in unsedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2001;33:311-316.

19. Thota PN, Zuccaro G, Vargo JJ, et al. A randomized prospective trial comparing unsedated esophagoscopy via transnasal and transoral routes using a 4-mm video endoscope with conventional endoscopy with sedation. Endoscopy. 2005;37:559-565.

20. Dumortier J, Napoleon B, Hedelius F, et al. Unsedated transnasal EGD in daily practice: results with 1100 consecutive patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:198-204.

21. Murata A, Akahoshi K, Sumida Y, et al. Prospective randomized trial of transnasal versus peroral endoscopy using an ultrathin videoendoscope in unsedated patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:482-485.

22. Trevisani L, Cifala V, Sartori S, et al. Unsedated ultrathin upper endoscopy is better than conventional endoscopy in routine outpatient gastroenterology practice: a randomized trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:906-911.

23. Preiss C, Charton JP, Schumacher B, et al. A randomized trial of unsedated transnasal small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) versus peroral small-caliber EGD versus conventional EGD. Endoscopy. 2003;35:641-646.

24. Dean R, Dua K, Massey B, et al. A comparative study of unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy and conventional EGD. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:422-424.

25. Saeian K, Staff DM, Vasilopoulos S, et al. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy accurately detects Barrett’s metaplasia and dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:472-478.

26. Jobe BA, Hunter JG, Chang EY, et al. Office-based unsedated small-caliber endoscopy is equivalent to conventional sedated endoscopy in screening and surveillance for Barrett’s esophagus: a randomized and blinded comparison. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2693-2703.

27. Postma GN, Belafsky PC, Aviv JE. Atlas of Transnasal Esophagoscopy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

28. Andrus JG, Dolan RW, Anderson TD. Transnasal esophagoscopy: a high-yield diagnostic tool. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:993-996.

29. Reavis KM, Morris CD, Gopal DV, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms better predict the presence of esophageal adenocarcinoma than typical gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Ann Surg. 2004;239:849-856.

30. Kim MK, Deschler DG, Hayden RE. Flexible esophagoscopy as part of routine panendoscopy in ENT resident and fellowship training. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001;80:49-50.

31. Postma GN, Bach KK, Belafsky PC, et al. The role of transnasal esophagoscopy in head and neck oncology. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:2242-2243.

32. Bach KK, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Evaluation of flaps following pharyngoesophageal reconstruction. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002;81:766.

33. Saeian K, Townsend WF, Rochling FA, et al. Unsedated transnasal EGD: an alternative approach to conventional esophagogastroduodenoscopy for documenting Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:297-301.

34. Saeian K, Staff D, Knox J, et al. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy: a new technique for accurately detecting and grading esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2246-2249.

35. Parham K. Detection of Barrett’s esophagus using transnasal esophagoscopy with narrow-band imaging. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(5):953-954.

36. Rees CJ, Belafsky PC. Chronic esophageal stricture with Barrett’s esophagus. Ear Nose Throat J. 2007;86:88.

37. Chiu YC, Hsu CC, Chiu KW, et al. Factors influencing clinical applications of endoscopic balloon dilation for benign esophageal strictures. Endoscopy. 2004;36:595-600.

38. Rowe-Jones JM, George CD, Moore-Gillon V, et al. Balloon dilatation of the pharynx. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1993;18:102-107.

39. Lang T, Hümmer HP, Behrens R. Balloon dilation is preferable to bougienage in children with esophageal atresia. Endoscopy. 2001;33:329-335.

40. Postma GN, Belafsky PC, Koufman JA. Dilation of an esophageal stricture caused by epidermolysis bullosa. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002;81:86.

41. Bach KK, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Esophageal papillomatosis with stricture. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;83:19.

42. Vaghela HM, Moir AA. Hydrostatic balloon dilatation of pharyngeal stricture under local anaesthetic. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:56-58.

43. Singer MI, Blom ED. An endoscopic technique for restoration of voice after laryngectomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1980;89:529-533.

44. Bach KK, Postma GN, Koufman JA. In-office tracheoesophageal puncture using transnasal esophagoscopy. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:173-176.

45. Doctor VS, Enepekides DJ, Farwell DG, et al. Transnasal oesophagoscopy-guided in-office secondary tracheoesophageal puncture. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122(3):303-306.

46. Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Kaufman JA. Replacement of a failed tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP) under direct vision. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001;80:862.

47. Belafsky PC, Allen K, Castro-Del Rosario L, et al. Wireless pH testing as an adjunct to unsedated transnasal esophagoscopy: the safety and efficacy of transnasal telemetry capsule placement. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:26-28.