Chapter 37 Translabyrinthine Vestibular Neurectomy

Deafferentation of the peripheral vestibular system continues to play a role in the management of patients with fluctuating or poorly compensated vestibulopathy that remains refractory to medical therapies or vestibular rehabilitation. In various peripheral vestibular disorders, abnormal spontaneous or motion-induced inputs that conflict with normal contralateral responses can create symptoms of dizziness, imbalance, vertigo, motion intolerance, and visual instability (i.e., oscillopsia) with a resulting negative impact on quality of life.1 Removing these dynamic vestibular signals generated from the abnormal ear can create a static vestibular lesion, for which the brain is more easily able to compensate.2

Deafferentation of the peripheral vestibular system can be produced through surgical or chemical labyrinthectomy, vestibular nerve section (i.e., neurectomy or neurotomy), or a combination thereof. Although chemical labyrinthectomy may produce either a partial or a total loss of peripheral vestibular function from the affected ear,3,4 surgical labyrinthectomy or vestibular nerve section reliably produces a complete lesion.5 Chemical labyrinthectomy destroys the sensory hair cells of the semicircular canals (SSC) and otolithic organs, whereas surgical labyrinthectomy comprehensively removes the contents of the vestibular labyrinth. Conversely, vestibular nerve section more proximally creates deafferentation by interrupting the transduction of the abnormal neural impulses from the labyrinth to the brainstem. Both surgical procedures allow for direct pathologic assessment of tissues, which may be necessary in certain instances. Each of these approaches has merits and disadvantages, and must be chosen on an individualized basis for the patient and his or her condition.

This chapter focuses on translabyrinthine vestibular nerve section. This procedure, by necessity, combines the advantages of labyrinthectomy and vestibular nerve section, including (1) dual deafferentation of the peripheral vestibular end organs and (2) direct pathologic assessment of the contents of the vestibular labyrinth and the internal auditory canal (IAC). By removing preganglionic and postganglionic neural elements, a more complete vestibular lesion may be produced, especially in cases where previous labyrinthectomy or vestibular nerve section attempts have failed.6 Examination of the tissues may reveal inflammatory or neoplastic processes that require further medical attention.6,7

HISTORY

Charcot, in 1874, and later Frazier8 initially described neurectomy of the vestibulocochlear nerve. Subsequently, in 1928, Dandy9 strongly advocated intracranial sectioning of the eighth cranial nerve for paroxysmal vertigo symptoms. Although he noted that the procedure often was successful for relieving troubling vertigo, patients typically had a complete hearing loss in the operated ear. McKenzie,10 in 1931, developed a selective neurectomy technique, preserving auditory function in some cases. Some 30 years later, House11 developed the middle fossa and translabyrinthine approaches for vestibular nerve sectioning. Later modifications by Fisch and Glasscock and colleagues12–14 refined these approaches. The importance of preserving not only the cochlear nerve, but also the labyrinthine blood supply as a critical premise for hearing preservation was realized. Silverstein and colleagues15,16 later described in detail the complex interrelationship of the vestibular and cochlear nerve fibers in the cerebellopontine angle, allowing for even more selective neurectomy near the root entry zone in the brainstem. Over the last 50 years, Hitselberger and his colleagues can be credited with performing vestibular nerve section procedures on hundreds of patients with peripheral vestibular disorders.17 Today, successful vestibular nerve section relies on the anatomic and surgical principles developed by these pioneers.

DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS

Selecting an appropriate surgical intervention for patients with peripheral vestibular disorders is challenging. In considering such therapy, a diagnosis must first be rendered or, minimally, an affected ear must be identified. Although a detailed discussion regarding the diagnosis and management of vestibular disorders is beyond the scope of this chapter, an understanding of the various vestibular disorders is crucial to identifying a correct diagnosis and making an adequate treatment recommendation.18,19 Establishing the correct diagnosis may be difficult sometimes, and can require the input from various professionals in differing disciplines. Vertigo is the cardinal symptom of a vestibular system disorder. It is also important to recognize that many cases of dizziness are not related to the vestibular system at all, and dizziness without vertigo is common. When vertigo is absent, the diagnosis of vestibular disorder should be carefully scrutinized. Although the presence of vertigo can be of either central or peripheral origin, most cases of vertigo arise from the peripheral vestibular apparatus (SSC, otolithic organs, or vestibular nerves).

Although most of these peripheral vestibular disorders manifest to the clinician with a clear clinical picture, occasionally differentiation from the common central causes of vertigo is difficult. Differentiation among the peripheral and central varieties of vertigo takes on even greater significance when ear-specific therapies are being contemplated. When peripheral deafferentation is considered in the treatment regimen, defining the peripheral cause and the affected labyrinth is crucial. The most common causes of peripheral (or ear-related) vertigo in adult patients include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Meniere’s disease, and vestibular neuronitis. More recently, superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SSCD) syndrome has become more frequently recognized.20,21 Common central causes of vertigo include migraine-related dizziness (also known as migraine vestibulopathy22), transient ischemic attack, and demyelinating disease such as multiple sclerosis and stroke.

Meniere’s disease is characterized by episodic vertigo that lasts minutes to hours with associated, fluctuating aural symptoms, including hearing loss, tinnitus, and pressure. Audiometric testing characteristically reveals a low-frequency sensorineural hearing impairment. In contrast, BPPV is characterized by brief (<20 seconds), position-induced attacks of vertigo in the absence of other auditory symptoms. Symptoms in these patients can be reproduced with the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, which often reveals a torsional nystagmus when the head is positioned with the affected ear in a gravity-dependent position. By contrast, vestibular neuronitis typically is considered when patients experience a single, prolonged (i.e., days) attack of vertigo, without associated auditory symptoms, which is followed by a period (i.e. days to weeks) of motion intolerance or BPPV or both. SSCD syndrome is characterized by symptoms of vertigo or dizziness induced by sound or pressure applied to the affected ear or via a Valsalva maneuver.20,21 Typically, auditory symptoms include hearing loss, pressure, and occasionally pulsatile tinnitus. In this disorder, audiometric testing commonly reveals a conductive hearing loss with preserved acoustic reflexes.

Migraine-related dizziness is common and can masquerade as any of the aforementioned vestibular disorders.22,23 It is characterized by episodic vertigo or dizziness that can last seconds to hours or even days. It may or may not be associated with headache, visual, or auditory symptoms. When retro-orbital headache and visual scotoma are associated with vertigo attacks, the diagnosis is seldom difficult. Symptoms often may abate following sleep, adding credence to the diagnosis. Patients with migraine-related dizziness frequently relate a history of motion or sound intolerance, however, in periods between attacks similar to individuals with BPPV and SSCD syndrome. Migraine-related vertigo may also be associated with a classic Meniere’s disease history, which can make distinguishing these disorders extremely difficult, especially when there is no hearing loss. Patients with migraine-related dizziness can have ENG abnormalities and can respond to diuretic therapies similar to patients with Meniere’s disease.24 All otologists who manage patients with vertigo should have a very high index of suspicion for this disorder. When patients have episodic vertigo in the absence of objective evidence of hearing loss, migraine-related dizziness must be ruled out before considering ear-specific therapy.

TREATMENT OF VESTIBULAR DISORDERS: AN OVERVIEW

Ear-specific therapies include destructive and nondestructive therapies. Destructive therapies are therapies that induce either partial or total vestibular deafferentation with or without hearing loss. Nondestructive therapies include endolymphatic sac procedures, intratympanic steroids,25 and transtympanic pressure therapy26 in patients with Meniere’s disease. For patients with SSCD syndrome, tympanostomy tube placement to control pressure-induced symptoms could also be considered as a nondestructive therapy. Canalith repositioning maneuvers are ear-specific therapies that often resolve unwanted positional vertigo in patients with BPPV.

As a last resort, destructive or deafferentation procedures are considered for patients with symptoms that remain refractory to the aforementioned approaches. Deafferentation can be accomplished by either chemical or surgical means, and can be directed at the receptors of the inner ear, the vestibular afferent fibers to the brain, or some combination thereof. When the labyrinth remains intact, these procedures can be undertaken with the intent of hearing preservation. Hearing-preserving total labyrinthine deafferentation procedures include vestibular nerve sectioning5,27 and intratympanic gentamicin.28 For patients with BPPV, partial deafferentation can be accomplished by partitioning of the affected posterior SCC while maintaining hearing.29 Likewise, patients with SSCD can achieve control of symptoms with surgery directed at occlusion of the affected superior SCC, often with improvement in hearing.30 When hearing is not an issue, transmastoid labyrinthectomy or translabyrinthine vestibular nerve sectioning can reliably provide comprehensive vestibular deafferentation.

Decision Making

The selection of a procedure for a particular patient depends on the frequency and severity of symptoms and the associated effect on quality of life, hearing status, and patient and otologist preference. Nondestructive procedures should be considered before destructive ones because the consequences of deafferentation using either chemical or surgical means include acute, post-treatment dizziness or vertigo or both with associated imbalance. Although compensation generally occurs after weeks to months, supplementary vestibular rehabilitation therapy is often needed.31 Despite all efforts, patients who have undergone deafferentation are often left with some residual imbalance that is refractory to physical therapy.5,32 These patients can be notably discouraged by such an outcome. Before undertaking deafferentation, patients should understand what it can accomplish—control of unwanted spontaneous or motion-induced attacks of vertigo. This control frequently comes at the expense of having some permanent degree of imbalance and motion intolerance, at least in sensory-deprived situations, such as during ambulation in the dark or while on an unstable surface or in periods of relative weightlessness.

When considering a destructive procedure, knowing what constitutes useful hearing is also crucial. Classically, serviceable hearing was defined as a pure tone average equal or better than 50 dB HL and a speech reception score (W22 word lists) of less or equal than 50% correct.33 In this regard, patients with hearing in an affected ear worse than this definition were considered for hearing sacrifice, whereas patients with better hearing were considered for a hearing-preserving approach. Subsequently, a classification scheme was developed by Shelton and Hitselberger,34 and later modified and adopted by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.35 This scheme defines good hearing (class A, pure tone average 30 dB, standard deviation score 70%), serviceable hearing (class B, pure tone average 50 dB, standard deviation score 50%), measurable hearing (class C, any measurable hearing loss), and a “dead ear” (class D, absence of measurable hearing).

Transmastoid Labyrinthectomy versus Translabyrinthine Vestibular Nerve Section for Deafferentation

Similar to transmastoid labyrinthectomy, translabyrinthine vestibular nerve section (TLVNS) results in a complete labyrinthectomy. In addition, preganglionic nerve sectioning, proximal to Scarpa’s ganglion, is accomplished.6,36 By necessity, TLVNS opens the IAC, exposing the patient to potential cerebrospinal fluid leakage and other intracranial complications.

Previous investigators have suggested that failed labyrinthectomy or vestibular nerve section might also occur because of the development of a postsurgical neuroma in the labyrinth or at the cut ends of the vestibular nerves.6,7,36 Traumatic neuromas can result in spontaneous neural impulses through either ephaptic transmission or neural crosstalk.37 These spontaneous impulses can presumably result in conflicting information at the level of the brainstem nuclei, creating vertigo and dizziness. Finally, some neurotologists might consider the dual denervation accomplished by TLVNS as the most reliable method for eliminating ear-related vertigo in patients with poor hearing, and would use this as their primary approach in selected cases. The use of TLVNS as a primary form of deafferentation must be balanced against the additional risks of dural opening in an individual patient.

PREOPERATIVE TESTING

Functional Vestibular System Assessment

Electronystagmography

Before vestibular deafferentation, the ENG test battery serves to delineate the peripheral vestibular reactivity of each ear. This delineation may help determine the affected side if this is not clinically obvious. In cases of known laterality, ENG can rule out an unsuspected, contralateral peripheral vestibular deficit, preventing unwanted bilateral, vestibular hypofunction.5

Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

The clinical utility of VEMP testing is primarily for documenting inferior vestibular nerve function or dysfunction, and assisting in the diagnosis of SSCD syndrome. For patients with SSCD syndrome, VEMP thresholds are classically reduced compared with unaffected ears.20 For patients contemplating deafferentation, the usefulness of the results of VEMP testing remains to be determined. It seems that the clinical utility of VEMP testing can be thought of as being similar to ENG testing. That is, VEMP testing might be useful to determine the affected side if this is not clinically obvious. In cases of known laterality, VEMP might help rule out an unsuspected, contralateral peripheral vestibular deficit, preventing unwanted bilateral, vestibular hypofunction.

Platform Posturography

Platform posturography can be used to determine the overall functional impact of a particular vestibular disorder on balance. This test can provide some information regarding visual, vestibular, proprioceptive, and motor contributions to balance function.38 Although this test may not be helpful preoperatively for decision making, serial posturography may allow for a better assessment of the effects of postoperative vestibular rehabilitation efforts.

Anatomic Vestibular and Auditory System Assessment

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI should be part of the diagnostic work-up for patients with persistent balance and equilibrium problems. Specifically, MRI should be used to assess possible central and retrocochlear pathology.39 An adequate study should be furnished as a high-resolution study with at least 1.5 T and should include T1-weighted and T2-weighted studies. Also, a contrast-enhanced T1-weighted series should be obtained. A continuous interference in a steady state (CISS) sequence might help to delineate each nerve within the IAC, and is generally part of a CN VIII protocol used in most institutions.

High-Resolution Computed Tomography

Some authors supplement MRI with a high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan of the temporal bones. High-resolution CT provides visualization of bony structures and can delineate middle ear and mastoid anatomy. High-resolution CT remains the gold standard to determine the anatomic integrity of the superior SCC and should be used to rule out superior SSCD.40

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

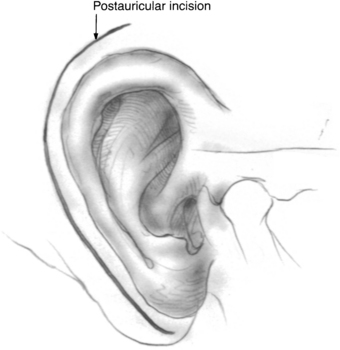

An incision is made approximately 1 cm above and behind the postauricular crease and follows the contour of the auricle (Fig. 37-1). A plane is established in the galea aponeurotica lateral to the temporalis muscle, and the auricle is turned forward. This layer is best established directly over the temporalis fascia superiorly and over the mastoid periosteum inferiorly. The musculoperiosteal flap is incised separately and elevated off the mastoid cortex with the help of a periosteal elevator or monopolar electrocautery. This flap is moved forward to the level of the posterior external auditory canal and mastoid tip, and subsequently fixed with a large self-retaining retractor. Care is taken not to create an opening in the external auditory canal skin because this can provide a route for cerebrospinal fluid leakage postoperatively.

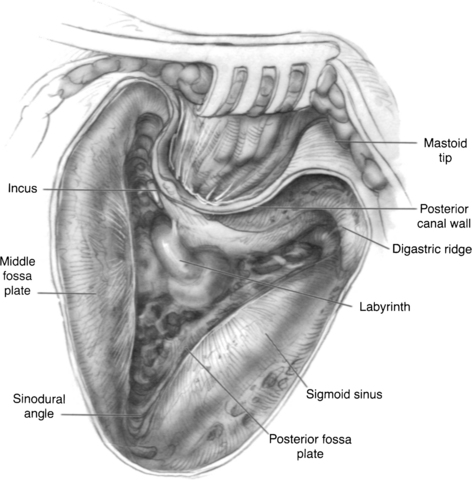

The high-speed drill with a large cutting burr and constant suction-irrigation is used to perform a cortical mastoidectomy. The posterior aspect of the external auditory canal wall and the bone overlying the inferior temporal lobe dura is thinned, and the sigmoid sinus is skeletonized (Fig. 37-2). The mastoid antrum, horizontal SCC, and short process of the incus are brought into clear view. For the sigmoid sinus, an eggshell of bone is usually left over the vein wall to protect it from manipulation during deeper dissection. Some surgeons leave a larger bony island over the sinus to compress it medially and gain better exposure of the medial temporal bone. The sinodural angle is opened as far posteriorly on the cortex as possible. Because the vestibule lies medial to the facial nerve, a tangential view is facilitated by this additional exposure.

Before labyrinthectomy and subsequent permanent hearing loss, the operative consent, audiogram, and ENG are reviewed again as an additional level of safety. The labyrinthectomy is initially carried out using a 3 or 4 mm cutting burr. First, the horizontal SCC is half-opened on its superior border from the ampulla anteriorly to the intersection with the posterior SCC. The horizontal SCC is initially only half-opened to protect the external genu of the facial nerve inferiorly. Next, the posterior SCC is opened and traced superiorly to its confluence with the superior SCC (i.e., common crus) (Fig. 37-3). The common crus may be followed directly toward the vestibule (Fig. 37-4). The superior SCC is also opened along the entire path to the ampulla. During this maneuver, care is taken not to damage the temporal lobe dura, which usually lies in very close approximation to the superior SCC lumen.

The superior and posterior surfaces of the external genu of the facial nerve are now carefully identified to facilitate dissection of the posterior SCC ampulla, which lies more medially. Inferior dissection in the retrofacial air cell tract beyond the posterior SCC ampulla is unnecessary in this procedure, and might reveal the jugular bulb. When the three SCC ampullae and the common crus have been opened to the vestibule, the spherical and elliptical recesses of the vestibule and the endolymphatic duct can be appreciated. At this point, all soft tissue elements of the membranous labyrinth are removed. This step would be the normal end point for postganglionic, transmastoid labyrinthectomy (Fig. 37-5).

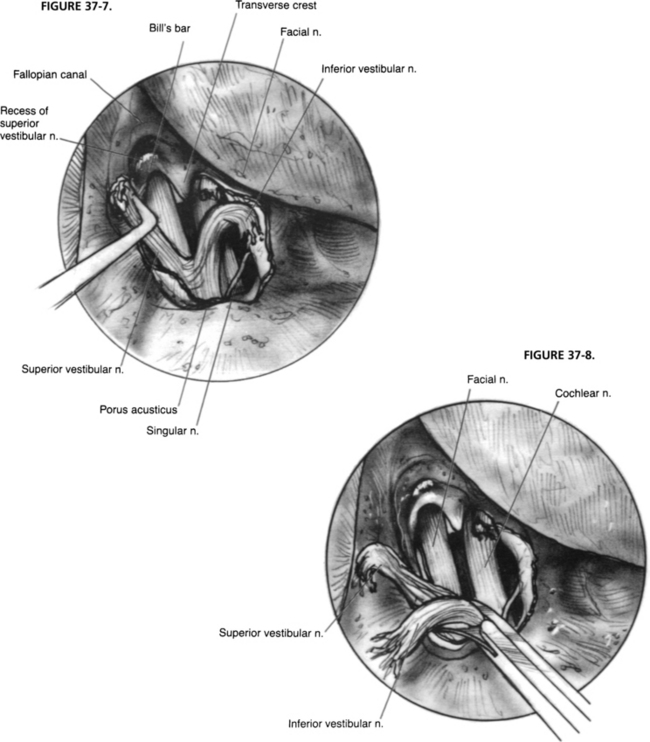

When the IAC dura is identified medially, further anterior dissection superior and inferior to the canal allows for the creation of “troughs.” These troughs should create approximately 270 degrees of dural exposure over the medial two thirds of the IAC (Fig. 37-6). The superior trough is bounded superiorly by the temporal lobe dura and inferiorly by the IAC dura. The inferior trough is bounded superiorly by the IAC dura and inferiorly by the cochlear aqueduct and jugular bulb. Frequently, air cells are encountered in the superior trough above the IAC. In the inferior trough, dissection usually reveals the cochlear aqueduct as a fibrous tissue–containing tract that elutes cerebrospinal fluid. Inferior dissection below the aqueduct should be avoided because the lower cranial nerves can be at risk in this region. Finally, dural decompression of the lateral aspect of the IAC should proceed to identify the vertical and the horizontal crests of the IAC, and subsequently the facial nerve in its labyrinthine segment.

After drilling is complete, bone chips are removed, and the dura is opened. Dural opening is accomplished via sharp dissection. The safest way to identify the intradural facial nerve is by careful palpation of Bill’s bar with visualization of the labyrinthine segment. The superior vestibular nerve is avulsed from its labyrinthine attachment, and the soft tissue plane between the vestibular and facial nerves is developed. The inferior vestibular nerve is transected similarly and dissected medially (Fig. 37-7). Scarpa’s ganglion lies approximately midway within the IAC portion of the nerve. If pathologic assessment is needed, a portion of the nerve is removed and sent to the laboratory (Fig. 37-8). Although the cochlear nerve may also be sectioned, this action would preclude its use in future cochlear implantation if that opportunity arises.41

Closure is accomplished by first plugging the eustachian tube and then closing the dural defect and wound. The eustachian tube is addressed through the facial recess by placing a piece of absorbable knitted fabric (Surgicel) deeply in to the tubal lumen. Secondarily, pieces of muscle usually from the temporalis are packed into the eustachian tube and middle ear up to the facial recess opening; another sheet of Surgicel holds this in place. The dural opening is closed by careful packing with strips of abdominal fat placed partly through the opening.42 With such a small defect, a watertight closure is usually attained with a few carefully placed pieces. A titanium mesh placed over the mastoid cortex opening is often helpful to bolster the fat in place.43 The wound is closed in layers with an interrupted absorbable suture, and a firm mastoid dressing is placed.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient is watched in the intensive care unit for a day with hourly neurologic checks and then is moved to a step-down room when neurologic stability is ensured. If an abdominal wound drain was used, this is removed on postoperative day 1. Antibiotics are discontinued after 24 hours so as not to promote infection with resistant organisms. Patients are encouraged to sit up and dangle their legs off the side of the bed on the 1st or 2nd postoperative day, and to begin ambulation with help as soon as possible. Ambulation and activity are usually limited by the degree of vertigo, nausea, and vomiting. These symptoms are usually controlled medically with vestibular suppressants, such as droperidol, diazepam, meclizine, and dimenhydrinate. When static compensation is sufficient, ambulation is usually possible with some assistance. At this point, head movements still elicit significant vertigo and are usually avoided. Discharge is possible when the patient is able to ambulate and tolerate a diet; however, driving is contraindicated until head movement does not cause dizziness. This level of activity usually requires dynamic compensation to occur. This process can take weeks to occur, and may require a course of vestibular rehabilitation therapy to become complete.31

The rate of static compensation for vertigo while in the hospital is predicted by the severity of the postoperative nystagmus. Horizontal spontaneous nystagmus is evident in all three directions of gaze (third-degree nystagmus) on the 1st or 2nd postoperative days. According to Alexander’s law, as the level of static compensation increases as a result of alterations in the vestibular nuclei tonic discharge rate, nystagmus becomes evident only in central and contralateral gazes (second-degree nystagmus). When further compensation occurs, nystagmus may be evident only on contralateral gaze (first-degree nystagmus). This level of nystagmus usually coincides with the patient’s ability to ambulate and readiness for discharge around the 5th to 7th postoperative day.18

COMPLICATIONS

Complications seen with TLVNS may include cerebrospinal fluid leak, meningitis, and facial paralysis.6,36,44 Facial paralysis can be considered the consequence of working in an area in which the nerve is anatomically at risk. Avoidance is the best solution to this problem: the surgeon should be certain of the nerve’s location and treat it with respect.45 Postoperative steroids or limited decompression of the nerve, particularly in the labyrinthine segment, may be useful in preventing sequelae when the nerve is known to have been traumatized. When fever and meningismus occur, a lumbar puncture is performed, and appropriate antibiotic coverage is instituted to treat bacterial meningitis. This complication is rare.

Cerebrospinal fluid leakage occurs in less than 5% of TLVNS cases using the previously described techniques. This low incidence is likely due to the limited dural opening needed for this procedure and careful closure. If wound leakage occurs, this can be managed with simple oversewing at the bedside. If rhinorrhea occurs, this is managed with a firm pressure bandage, head of bed elevation, and lumbar subarachnoid drainage for 5 days.46 If resolution of the leak is not seen after aggressive drainage, the wound is explored, and the adipose plug is readjusted.

RESULTS AND LITERATURE OVERVIEW

TLVNS is successful at relieving spontaneous attacks of vertigo in 75% to 95% of patients with Meniere’s disease; it is substantially less successful in patients with vertigo not related to Meniere’s disease.36,47 These findings suggest that our ability to diagnose the disorder correctly as one of the peripheral vestibular apparatus or ability to induce stable and complete central vestibular compensation remains imperfect.5,6,32

1. Green J.D.Jr., Verrall A., Gates G.A. Quality of life instruments in Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1622-1628.

2. Igarashi M. Vestibular compensation: An overview. Acta Otolaryngol. 1984;406:78-82.

3. Hoffmann K.K., Silverstein H. Inner ear perfusion: Indications and applications. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11:334-339.

4. Blakley B.W. Clinical forum: A review of intratympanic therapy. Am J Otol. 1997;18:520-526.

5. Eisenman D.J., Speers R., Telian S.A. Labyrinthectomy versus vestibular neurectomy: Long-term physiologic and clinical outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:539-548.

6. Monsell E.M., Brackmann D.E., Linthicum F.H.Jr. Why do vestibular destructive procedures sometimes fail? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;99:472-479.

7. Linthicum F.H.Jr., Alonso A., Denia A. Traumatic neuroma: A complication of transcanal labyrinthectomy. Arch Otolaryngol. 1979;105:654-655.

8. Frazier C.H. Intracranial division of the auditory nerve for persistent aural vertigo. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1912;15:524-529.

9. Dandy W.E. Intracranial division of the vestibular portion of the auditory nerve for Meniere’s disease. Arch Surg. 1928;16:1127-1152.

10. McKenzie K.G. Intracranial division of the vestibular portion of the auditory nerve for Meniere’s disease. Can Med Assoc J. 1936;34:369-381.

11. House W.F. Surgical exposure of the internal auditory canal and its contents through the middle, cranial fossa. Laryngoscope. 1961;71:1363-1385.

12. Fisch U. Vestibular and cochlear neurectomy. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1974;78:ORL252-ORL255.

13. Glasscock M.E.III, Kveton J.F., Christiansen S.G. Middle fossa vestibular neurectomy: An update. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:216-220.

14. Glasscock M.E.III. The surgical treatment of vertigo. South Med J. 1973;66:526-530.

15. Silverstein H., Norrell H., Haberkamp T., et al. The unrecognized rotation of the vestibular and cochlear nerves from the labyrinth to the brain stem: Its implications to surgery of the eighth cranial nerve. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;95:543-549.

16. Silverstein H. Cochlear and vestibular gross and histologic anatomy (as seen from postauricular approach). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:207-211.

17. Nguyen C.D., Brackmann D.E., Crane R.T., et al. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: Evaluation of technical modification in 143 cases. Am J Otol. 1992;13:328-332.

18. Baloh R.W., Honrubia V. Clinical Neurophysiology of the Vestibular System, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

19. Baloh R.W., Halmagyi G.M. Disorders of the Vestibular System, 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996.

20. Minor L.B., Carey J.P., Cremer P.D., et al. Dehiscence of bone overlying the superior canal as a cause of apparent conductive hearing loss. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:270-278.

21. Minor L.B., Solomon D., Zinreich J.S., et al. Sound- and/or pressure-induced vertigo due to bone dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:249-258.

22. Brantberg K., Trees N., Baloh R.W. Migraine-associated vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:276-279.

23. Shepard N.T. Differentiation of Meniere’s disease and migraine-associated dizziness: A review. J Am Acad Audiol. 2006;17:69-80.

24. Furman J.M., Sparto P.J., Soso M., et al. Vestibular function in migraine-related dizziness: A pilot study. J Vestib Res. 2005;15:327-332.

25. Boleas-Aguirre M.S., Lin F.R., Della Santina C.C., et al. Longitudinal results with intratympanic dexamethasone in the treatment of Meniere’s disease. Otol Neurotol. 2008;29:33-38.

26. Gates G.A., Verrall A., Green J.D.Jr., et al. Meniett clinical trial: Long-term follow-up. Arch Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:1311-1316.

27. Rosenberg S.I., Silverstein H., Hoffer M.E., et al. Hearing results after posterior fossa vestibular neurectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:32-37.

28. Cohen-Kerem R., Kisilevsky V., Einarson T.R., et al. Intratympanic gentamicin for Meniere’s disease: A meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:2085-2091.

29. Parnes L.S., McClure J.A. Posterior semicircular canal occlusion in the normal hearing ear. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:52-57.

30. Limb C.J., Carey J.P., Srireddy S., et al. Auditory function in patients with surgically treated superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:969-980.

31. Whitney S.L., Rossi M.M. Efficacy of vestibular rehabilitation. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000;33:659-672.

32. Teufert K.B., Berliner K.I. De la Cruz A: Persistent dizziness after surgical treatment of vertigo: An exploratory study of prognostic factors. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:1056-1062.

33. De la Cruz A., Teufert K.B., Berliner K.I. Surgical treatment for vertigo: Patient survey of vertigo, imbalance, and time course for recovery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:541-548.

34. Shelton C., Hitselberger W.E. The treatment of small acoustic tumors: Now or later? Laryngoscope. 1991;101:925-928.

35. Monsell E.M. New and revised reporting guidelines from the Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium. American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, Inc. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113:176-178.

36. De La Cruz A., Teufert K.B., Berliner K.I. Transmastoid labyrinthectomy versus translabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: Does cutting the vestibular nerve make a difference in outcome? Otol Neurotol. 2007 Sep;28(6):801-808.

37. Rasminsky M. Spontaneous activity and cross-talk in pathological nerve fibers. Assoc Res Nerv Mental Dis. 1987;65:39-49.

38. Monsell E.M., Furman J.M., Herdman S.J., et al. Computerized dynamic platform posturography. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:394-398.

39. Sedwick J.D., Gajewski B.J., Prevatt A.R., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the search for retrocochlear pathology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124:652-655.

40. Minor L.B. Superior canal dehiscence syndrome. Am J Otol. 2000;21:9-19.

41. Facer G.W., Facer M.L., Fowler C.M., et al. Cochlear implantation after labyrinthectomy. Am J Otol. 2000;21:336-340.

42. House J.L., Hitselberger W.E., House W.F. Wound closure and cerebrospinal fluid leak after translabyrinthine surgery. Am J Otol. 1982;4:126-128.

43. Fayad J.N., Schwartz M.S., Slattery W.H., et al. Prevention and treatment of cerebrospinal fluid leak after translabyrinthine acoustic tumor removal. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:387-390.

44. Langman A.W., Lindeman R.C. Surgery for vertigo in the nonserviceable hearing ear: Transmastoid labyrinthectomy or translabyrinthine vestibular nerve section. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:1321-1325.

45. Dew L.A., Shelton C. Iatrogenic facial nerve injury: Prevalence and predisposing factors. Ear Nose Throat J. 1996;75:724-729.

46. Fishman A.J., Marrinan M.S., Golfinos J.G., et al. Prevention and management of cerebrospinal fluid leak following vestibular schwannoma surgery. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:501-505.

47. Nelson R.A. Translabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. In: Brackmann D.E., Shelton C., Arriaga M.A., editors. Otologic Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001:433-439.