Chapter 49 Translabyrinthine Approach

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

House1,2 first began removing acoustic tumors through the translabyrinthine approach in 1960. Physicians at the House Ear Clinic have been using this approach for most larger acoustic tumor removals. Since 1983, we have performed more than 2700 tumors using this approach. The translabyrinthine procedure allows excellent access to the cerebellopontine angle (CPA) and exposure of the entire facial nerve from the brainstem to the stylomastoid foramen. The approach is extradural through most of the surgery. The primary disadvantage is sacrifice of hearing.

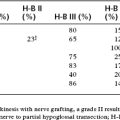

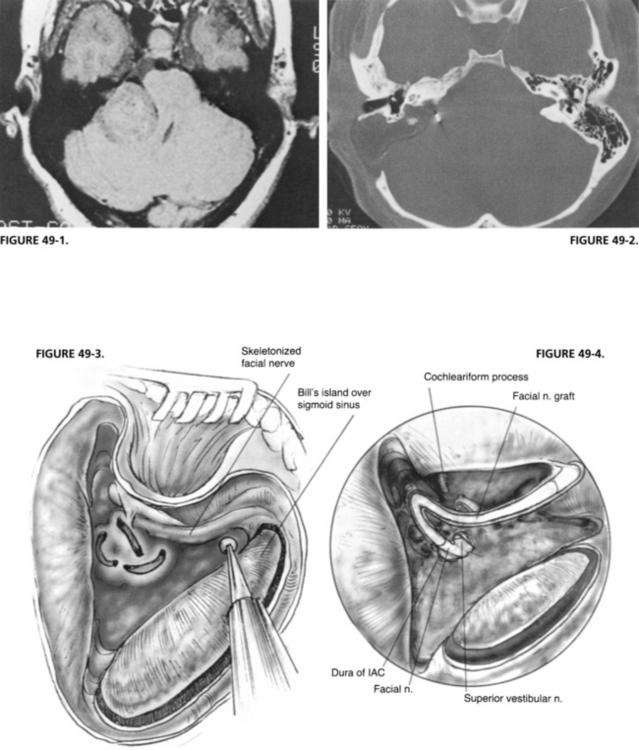

Regardless of the size of the tumor, the translabyrinthine approach is ideal for acoustic neuromas when the hearing is poor. It is also ideal for facial nerve lesions, such as neuromas; trauma owing to operative injury; or head trauma. The approach has many advantages. It is the most direct route to the structures of the CPA (Figs. 49-1 and 49-2).3 The lateral end of the internal auditory canal (IAC) can be dissected to ensure complete tumor removal from this area, and to allow consistent anatomic identification of the facial nerve.4 The approach for facial nerve lesions offers exposure of the mastoid, tympanic, and labyrinthine portions of the facial nerve. Identification of the facial nerve in the mastoid is facilitated after removal of the semicircular canals (Fig. 49-3). Because the labyrinth has been removed, the labyrinthine segment of the nerve is readily followed into the IAC. The IAC and CPA can be exposed widely if the lesion involves the facial nerve in the posterior fossa. The facial nerve is readily accessible from the brainstem to the stylomastoid foramen and beyond into the parotid gland. In addition to vestibular schwannoma removal, the translabyrinthine craniotomy approach is used for other tumors (e.g., meningiomas, cholesteatomas involving the petrous bone and posterior fossa, cholesterol granulomas, glomus tumors, and adenomas), for decompression of the facial nerve, and for repair of the facial nerve by either direct end-to-end anastomoses or nerve grafting (Fig. 49-4).

FIGURE 49-2. Postoperative CT scan of patient shown in Figure 49-1. Note extent of removal of bone from mastoid and labyrinth.

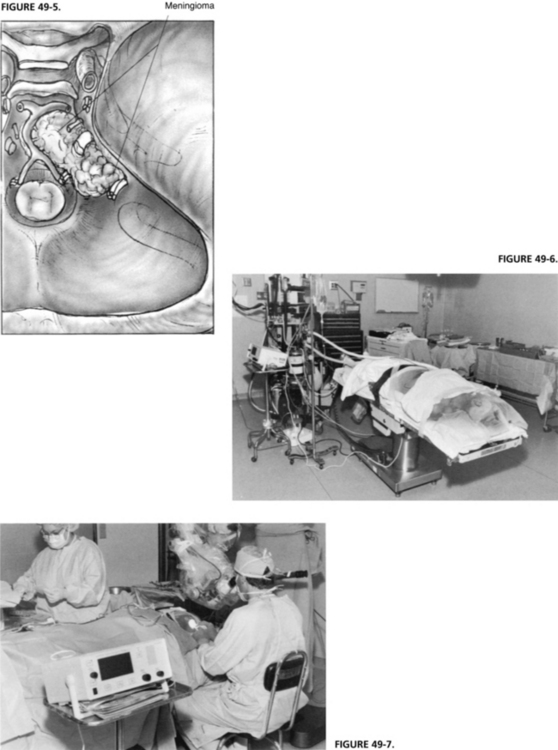

For tumors involving the area anterior to the internal auditory nerve at the clivus, the standard translabyrinthine approach is modified to allow anterior exposure (Fig. 49-5). The facial nerve is removed from the fallopian canal in the tympanic and mastoid segments and is reflected anteriorly. The cochlea is removed to provide excellent exposure anterior to the IAC (see Chapter 52).

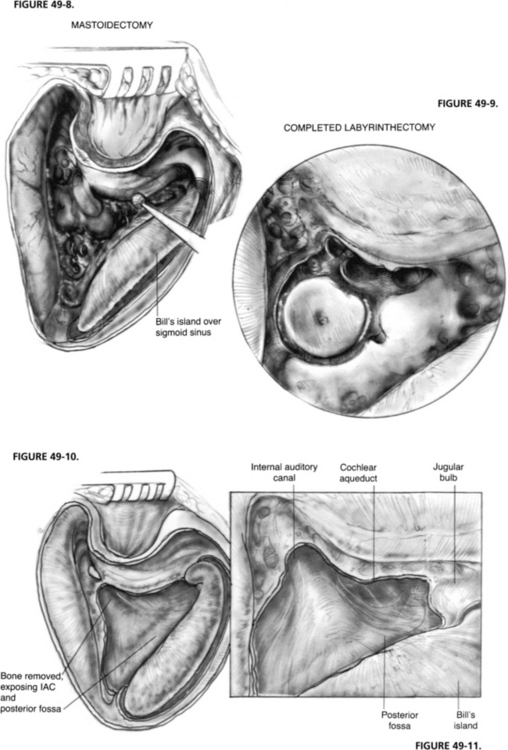

A major advantage of the translabyrinthine approach is that the patient is in the supine position with the head turned away from the surgeon (Figs. 49-6 and 49-7). This position eliminates some of the possible complications of the classic suboccipital approach to the CPA in which the sitting position is used, such as risks of air embolism and injury to the cerebellum from retraction. Quadriplegia has been reported in association with the sitting position.5 The translabyrinthine approach poses diminished danger of air embolism and requires less retraction of the cerebellum. Much of the surgery is extradural, lessening the chances of injury to the brain. The extradural dissection also greatly decreases the seeding of bone dust into the subarachnoid space.

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

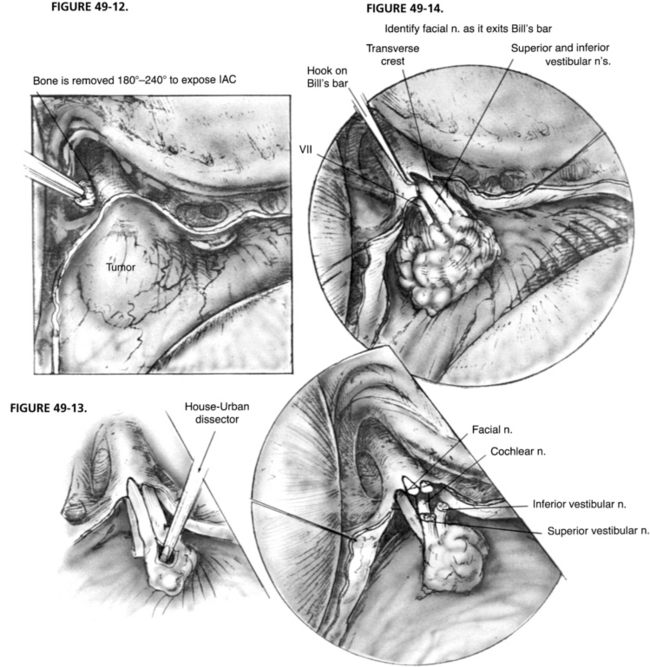

A complete mastoidectomy is performed with a high-speed drill with various sizes of cutting and diamond burrs. Removing bone 2 cm posterior to the sigmoid sinus is crucial for adequate exposure of the dura of the posterior cranial fossa. A small island of bone (Bill’s island—named for William F. House, who first suggested it) is left over the otherwise exposed sigmoid sinus (Fig. 49-8). This bony cover protects the sigmoid sinus from the shaft of the burr as the drilling proceeds medially to remove the labyrinth. The dissection continues with the removal of all bone covering the posterior fossa dura medial to the sigmoid sinus and down to the labyrinth. It is important to remove all bone over the sinal dural angle and a small amount of bone over the middle fossa dura adjacent to the angle. In larger tumors or contracted mastoids, we recommend removal of 2 to 3 cm of bone from temporal squama. We prefer to perform all of the lateral bone work before beginning the labyrinthectomy to obtain better exposure of the deep structures.

After the complete mastoidectomy is performed, and the bone is removed from posterior fossa dura, sigmoid sinus, and some of the middle fossa dura, the deepest point of dissection shifts to the sinal-dural angle. The labyrinthectomy begins with the removal of the lateral semicircular canal and extends posterior to the posterior canal. The bone removal is continued inferior and anterior toward the ampullated end of this canal (Fig. 49-9). The ampulla of the posterior canal is the landmark for the inferior border of the IAC. The inferior extent of bony removal is the jugular bulb. The posterior semicircular canal is opened inferiorly to the vestibule and superiorly to the common crus. The facial nerve is identified in its descending portion in the mastoid and skeletonized to just proximal to the stylomastoid foramen.

The common crus is opened to the vestibule. The superior canal is now opened and removed to its ampullated end in the vestibule. This portion of the superior canal identifies the area where the superior vestibular nerve exits the lateral end of the IAC and is in close proximity to the labyrinthine segment of the facial nerve. Similarly, the singular nerve exits the IAC at the posterior semicircular canal ampulla, and the inferior vestibular nerve exits the canal at the saccule and the spherical recess. Identification of these structures delineates the superior and inferior extent of the IAC. As the bone posterior to the IAC is removed, the vestibular aqueduct and the beginning of the endolymphatic sac are removed. An eggshell thickness of bone is left over the dura of the IAC to avoid injury to the underlying structures until all of the bony dissection is completed (Fig. 49-10).

The IAC is not entered at this time because bone must be removed medially to the porus acusticus. The IAC runs deep from the vestibule and away from the surgeon. A great deal of bone must be removed to expose the contents of the IAC and the CPA properly. Bone is removed around the canal superiorly and inferiorly to expose at least 270 degrees in circumference. The inferior limit of bone removal is the cochlear aqueduct and the jugular bulb. The cochlear aqueduct enters the posterior fossa directly inferior to the midportion of the IAC, superior to the jugular bulb (Fig. 49-11).6 It identifies the location of the neural compartment of the jugular foramen anterior to the jugular bulb. By not removing bone from anterior and deep to the cochlear aqueduct, injury to CN IX, X, and XI is avoided. Bone is removed from the inferior portion of the IAC and particularly the inferior lip, affording access to the inferior poll of the tumor in the CPA.

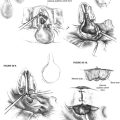

The facial nerve is identified as it exits the lateral end of the IAC at the vertical crest of bone (Bill’s bar) with a sharp 3 mm hook. The facial nerve may be identified further in its proximal labyrinthine segment by additional bone removal. The hook is passed carefully along the inside of the superior distal IAC until Bill’s bar is palpated (Fig. 49-12). It is not unusual for the facial nerve monitor to sound a warning as the hook passes along the nerve at the proximal portion of the fallopian canal.

With larger tumors, the size of the tumor is reduced by the use of the House-Urban (Fig. 49-13) or ultrasonic dissector. The surface of the tumor is carefully inspected first to identify nerves. Occasionally, the facial nerve is deflected posterior. The tumor capsule is incised, and the dissector is inserted to begin the intracapsular removal of the bulk of the tumor. Excessive manipulation of the tumor must be avoided to prevent traction of the facial nerve. The capsule of the tumor is collapsed toward its center, greatly facilitating its dissection from the CPA. The tumor is followed medially to the brainstem. The plane between the tumor and the brainstem is developed with sharp and blunt dissection. Cottonoids are placed between the brainstem and the tumor to protect the underlying structures. At this point, attempts are made to identify the facial nerve superiorly. It is usually anterior to the tumor, but may be draped over the top of it. CN IX is identified inferiorly. In large tumors, CN IX, X, and XI may be stretched over the inferior surface of the tumor. Manipulation of the tumor may cause a change in the pulse rate or blood pressure. During this phase of the tumor removal, use of a fenestrated neurotologic suction tip helps avoid injury to surrounding structures.7

The vestibular nerve and tumor are separated from the facial nerve in the IAC and carefully dissected medially to the porus acusticus and into the CPA (Fig. 49-14). Some tumors involve the lateral end of the IAC, complicating identification of the facial nerve in the canal. In these cases, bone is removed from the proximal fallopian canal to allow positive identification of the facial nerve where it is not involved with tumor. This maneuver greatly reduces injury to the facial nerve.

Management of the Contracted Mastoid

Using several crucial maneuvers, we have never altered our approach to the CPA based on anatomic variations.8 Wide removal of the bone of the temporal squama and presigmoid and postsigmoid posterior fossa dura overcomes the limitations imposed by a low-lying tegmen and anterior-placed sigmoid sinus. For a high jugular bulb, we recommend skeletonization along its anteromedial, medial, and posterior surfaces without compression. This skeletonization, combined with the ability to retract the widely exposed temporal lobe dura superiorly, provides an improved line of sight in the deep field of the CPA.

COMPLICATIONS

Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak

Before 1974, we used temporalis muscle to close the dura, and our incidence of CSF leak was 20%.2 Since we began using abdominal fat instead, this incidence has been reduced to less than 7% in translabyrinthine acoustic tumor removals.9 Since we began using titanium mesh for cranioplasty in mid-2003, our incidence of CSF rhinorrhea has been reduced to 3.3%.

RESULTS

Postoperative Follow-up

In our experience, vestibular schwannomas rarely recur after translabyrinthine removal. Our recurrence rate for unilateral tumors removed through the translabyrinthine approach treated between 1961 and 1995 was 0.3%.10 The average interval to recurrence was 10 years. Based on these findings, we have recommended a single gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study 5 years postoperatively.

NEUROSURGICAL TECHNIQUES IN ACOUSTIC TUMOR SURGERY

1. House W.F. Acoustic neuroma [Monograph]. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1964;80:598-757.

2. House W.F. Translabyrinthine approach. In: House W.F., Luetje C.M., editors. Acoustic Tumors Management. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1979:43-87. vol. 2

3. Brackmann D.E. Translabyrinthine removal of acoustic neurinomas. In: Brackmann D.E., editor. Neurological Surgery of the Ear and Skull Base. New York: Raven Press; 1982:235-241.

4. House W.F., Leutje C.M., editors. Acoustic Tumors Management. Baltimore: University Park Press, 1979. vol. 1

5. Hitselberger W.E., House W.F.. A warning regarding the sitting position for acoustic tumor surgery. [Editorial]. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 106, 1980, 69.

6. Brackmann D.E., Green D. Translabyrinthine approach for acoustic tumor removal. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992;25:311-329.

7. Brackmann D.E. Fenestrated suction for neuro-otologic surgery. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1977;84:975.

8. Friedman R.A., Brackmann D.E., van Loveren H.R., Hitselberger W.E. Management of the contracted mastoid in the translabyrinthine removal of acoustic neuroma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:342-344.

9. Rodgers G.K., Luxford W.M. Factors affecting the development of cerebrospinal fluid leak and meningitis after translabyrinthine acoustic tumor surgery. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:959-962.

10. Shelton C. Unilateral acoustic tumors: How often do they recur after translabyrinthine removal? Laryngoscope. 1995;105:958-966.

11. Brackmann D.E., Cullen R.D., Fisher L.M. Facial nerve function after translabyrinthine vestibular schwannoma surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:773-777.