Transient Benign Cutaneous Lesions in the Newborn

Anne W. Lucky

Introduction

Transient benign cutaneous lesions in the newborn are important to recognize. Not only can parents be reassured, but costly, unnecessary and erroneous evaluations and treatment of presumed serious diseases can be prevented. This chapter discusses the most common transient benign conditions seen in neonates. Table 7.1 summarizes 15 studies of the incidences of transient benign cutaneous lesions.1–15 In some instances, racial and ethnic background may determine significant differences in the incidence of a disorder. Several excellent reviews of these conditions are also available.16–24

TABLE 7.1

Incidence of common transient benign lesions in the neonate1–20

| (%) | |

| Epstein’s pearls | 56–89 |

| Sebaceous hyperplasia | 21–48 |

| Erythema toxicum | 7–41 |

| Miliaria | 1–15 |

| Mongolian spots | |

| African-American | 32.1–96 |

| Asian | 60–86 |

| Latino | ~65 |

| Caucasian | 3–13 |

| Iranian | 71 |

| Salmon patch | |

| African-American | 59 |

| Asian | 22 |

| Latino | 68 |

| Caucasian | 70 |

| Iranian | 26 |

Papules and pustules

Milia

Milia are common papules that occur primarily on the face and scalp (Fig. 7.1). Clinically, they are tiny (up to 2 mm), white, smooth-surfaced papules, which are usually discrete, but their numbers may vary from a few to several dozen. They may be present at birth in 40–50% of newborns25 or appear later in infancy. In a recent Spanish study of 1000 newborns, they occurred in 16.6%; 80% being on the face.26 Although they usually occur on the face, they may be found anywhere. Milia are tiny inclusion cysts within the epidermis that contain concentric layers of trapped keratinized stratum corneum. Primary milia are associated with pilosebaceous units arising from the infundibula of vellus hairs. Secondary milia usually appear after trauma and originate from a variety of epithelial structures, such as hair follicles, sweat ducts, sebaceous ducts, or epidermis.27 Neonatal milia are presumably primary. The diagnosis is a clinical one. If confirmation is needed, a small incision with the tip of a #11 blade can release the contents, which appear either as a smooth, white ball or keratinous debris.

The most important differential diagnosis of milia is from sebaceous hyperplasia (see below), which also presents with small white papules. However, sebaceous hyperplasia tends to be clustered around the nose and a bit more yellow, and occurs in large plaques. Milia may be associated with certain syndromes,25 including epidermolysis bullosa, where lesions appear in sites of healing erosions, and in orofacial–digital syndrome type I, which features congenital mouth malformations, distinct facial features, and brachydactyly.28 In these cases, milia are numerous and persistent.

Milia usually resolve spontaneously over several months without treatment. If persistent, lesions can be incised and expressed, but this is rarely necessary. Why they occur with increased frequency in the newborn period is unknown.

Oral mucosal cysts of the newborn (palatal cysts or epstein’s pearls, and alveolar cysts or bohn’s nodules) (SEE ALSO Chapter 30)

Epstein’s pearls and Bohn’s nodules are actually both similar to milia,25 being microkeratocysts29–31 located in the mouth. They are 1–2 mm, smooth, yellow to gray-white papules found singly or in clusters, most commonly on the median palatal raphe (68–81%). They also occur on the alveolar ridges (22%), more on the maxillary than the mandibular ridge, but rarely on both. They occur in 64–89% of normal neonates and are more common in Caucasian infants. A recent study from Taiwan of 420 neonates up to 3 days old examined by one dentist, revealed a 94% incidence of oral cysts.32

Although there is no consistent use of nomenclature in the literature, usually when on the palate, these lesions have been called Epstein’s pearls, and when on the vestibular or lingual surfaces of the alveolar ridges, Bohn’s nodules (Fig. 7.2), and on the crest of the alveolar ridges, dental lamina cysts. The latter are thought to be derived from the ectoderm of the tooth bud.33 Although Bohn and others had presumed that these were mucous gland cysts, more recent studies have shown them to be keratin cysts derived from the dental lamina. Both of these epidermal cysts occur in keratinized mucous membranes and form in embryonic lines of fusion. Epstein’s pearls originate from epithelial remnants after fusion of palatal shelves. In a recent study of 1021 Swedish neonates,31 most of the palatal cysts had discharged spontaneously and resolved by age 5 months. Interestingly, 17 children developed new palatal cysts postnatally. However, most of the alveolar cysts regressed. A study of 60 premature compared with 60 term infants showed a lower prevalence in the prematures (9% vs 30%).34 The diagnosis is clinical. Other congenital papules in the mouth include gingival (alveolar) cysts of the newborn, congenital epulis (granular cell tumor), lymphangiomas, mucoceles, and ranulas (see also Chapter 30).29

Perineal median raphe cysts and foreskin cysts

Other common locations for epidermal inclusion cysts are in the foreskin and along the ventral surface of the penis and scrotum (Fig. 7.3![]() ; see Fig. 9.8).35 These lesions tend to be larger than the milia that appear on the head and neck, and may represent a developmental abnormality of fusion with entrapment of epidermal or urethral cells. Histologically, they usually have a stratified squamous epithelial lining, but may have pseudostratified columnar epithelium or ciliated or mucus-secreting cells as well, depending on which part of the urethra they are derived from. They often will enlarge throughout infancy and/or seem to appear after the newborn period, often in young men.36 Some may be pigmented due to the presence of melanocytes and melanophages in the cyst lining.37 They are benign and asymptomatic, although they may require surgical removal because of their large size or if they become infected.

; see Fig. 9.8).35 These lesions tend to be larger than the milia that appear on the head and neck, and may represent a developmental abnormality of fusion with entrapment of epidermal or urethral cells. Histologically, they usually have a stratified squamous epithelial lining, but may have pseudostratified columnar epithelium or ciliated or mucus-secreting cells as well, depending on which part of the urethra they are derived from. They often will enlarge throughout infancy and/or seem to appear after the newborn period, often in young men.36 Some may be pigmented due to the presence of melanocytes and melanophages in the cyst lining.37 They are benign and asymptomatic, although they may require surgical removal because of their large size or if they become infected.

Miliaria

Miliaria is a general term for describing obstructions of the eccrine ducts.38 It occurs in 1–15% of normal neonates (Table 7.1). Miliaria occurs in infants in warm climates, or those who are being kept warm or are febrile. It is thus more common in non-air-conditioned nurseries and in hot, rather than in temperate climates.4,6 The clinical manifestations of miliaria vary, depending on the level of the obstruction.

In the immediate newborn period, the most common form of miliaria is the most superficial, miliaria crystallina (sudamina). In miliaria crystallina, ductal obstruction is subcorneal or intracorneal. Obstruction at this level leads to very superficial trapping of sweat under the stratum corneum, producing typical small, crystal-clear vesicles that resemble water droplets on the skin (Fig. 7.4). These vesicles are extremely fragile and may be wiped away on cleansing of the skin. Miliaria crystallina usually appears in the first few days of life, but there are reports of congenital lesions.39–42 Occasionally, there will be many neutrophils within the lesions, giving them a more pustular than vesicular appearance. The causes of ductal blockage or leakage are not known. Some authors, however, favor the hypothesis that the ductal occlusion is caused by extracellular polysaccharide substance (EPS) from Staphylococcus epidermidis.43 Miliaria crystallina is precipitated by environmental overheating or fever, with consequent superficial retention of sweat in the obstructed ducts and surrounding epidermis. The diagnosis is clinical, although a smear of the clear fluid contents of the vesicles shows an absence of cellular material or, at most, a few neutrophils. Reducing the ambient temperature or treating the fever will prevent and/or treat miliaria. Miliaria crystallina is benign, but could be mistaken for more serious vesicular or pustular disorders such as herpes simplex.

Miliaria rubra is also common in overheated or febrile infants. Other terms for this disorder include ‘heat rash’ and ‘prickly heat.’ Miliaria rubra presents as erythematous, 1–3 mm papules or papulopustules on the head, neck, face, scalp, and trunk (Figs 7.5![]() , 7.6). It can occur anywhere, but has a predilection for the forehead, upper trunk, and flexural or covered surfaces. The lesions are not follicular. When there is inflammation with multiple neutrophils in the lesions, as may be found under occlusion beneath monitor leads or bandages, miliaria rubra may look pustular and mimic worrisome conditions such as neonatal infections. Some authors subclassify this pustular form as miliaria pustulosa. Histologically, there is dermal inflammation around occluded eccrine ducts. The sweat duct obstruction is lower than in miliaria crystallina, but still intraepidermal. The diagnosis is made clinically, but if there is any doubt, a biopsy will confirm eccrine duct occlusion. The erythematous papules of miliaria rubra may mimic a variety of neonatal conditions, such as neonatal acne, as well as candidal, staphylococcal, or herpes simplex infections. Correcting the overheating is usually sufficient to manage miliaria.

, 7.6). It can occur anywhere, but has a predilection for the forehead, upper trunk, and flexural or covered surfaces. The lesions are not follicular. When there is inflammation with multiple neutrophils in the lesions, as may be found under occlusion beneath monitor leads or bandages, miliaria rubra may look pustular and mimic worrisome conditions such as neonatal infections. Some authors subclassify this pustular form as miliaria pustulosa. Histologically, there is dermal inflammation around occluded eccrine ducts. The sweat duct obstruction is lower than in miliaria crystallina, but still intraepidermal. The diagnosis is made clinically, but if there is any doubt, a biopsy will confirm eccrine duct occlusion. The erythematous papules of miliaria rubra may mimic a variety of neonatal conditions, such as neonatal acne, as well as candidal, staphylococcal, or herpes simplex infections. Correcting the overheating is usually sufficient to manage miliaria.

Miliaria profunda, the third and deepest level of sweat duct obstruction, has occlusion at or below the dermoepidermal junction. It is rare in the newborn period. In older children and adults, this deep obstruction causes white papules representing dermal edema and can prevent adequate sweating, leading to hyperthermia.

Sebaceous hyperplasia

Sebaceous hyperplasia is most prominent on the face, especially around the nose and upper lip, where the density of sebaceous glands is highest. It occurs in 21–48% of normal newborns (Table 7.1). Sebaceous hyperplasia appears as follicular, regularly spaced, smooth white-yellow papules grouped into plaques (Figs 7.7, 7.8![]() ). There is no surrounding erythema. Hormonal (androgen) stimulation in utero, which comes from either the mother or the infant, causes hypertrophy of sebaceous glands. Premature infants are less affected, but sebaceous hyperplasia occurs in nearly half of term newborns.6,7 Sebaceous hyperplasia gradually involutes in the first few weeks of life. The papules differ from milia, which are epidermal inclusion cysts, and are usually discrete, solitary, and whiter in color.

). There is no surrounding erythema. Hormonal (androgen) stimulation in utero, which comes from either the mother or the infant, causes hypertrophy of sebaceous glands. Premature infants are less affected, but sebaceous hyperplasia occurs in nearly half of term newborns.6,7 Sebaceous hyperplasia gradually involutes in the first few weeks of life. The papules differ from milia, which are epidermal inclusion cysts, and are usually discrete, solitary, and whiter in color.

Erythema toxicum neonatorum (toxic erythema of the newborn, ‘flea bite’ dermatitis)

Erythema toxicum is unquestionably the best-known benign eruption in the newborn period, occurring in approximately half of term newborns.40,43–45 Estimates of the incidence in large series range from 7% to 41% (Table 7.1), but frequencies as high as 72% have been reported.44 In a recent Spanish study of 1000 newborns, 16.7% were found to be affected in the first 72 h of life.46 The discrepancies in estimates of incidence may be due to the length of time these infants were observed. The presence of erythema toxicum has been well correlated with birthweight and gestational age.47 Other apparently associated environmental factors include first pregnancy, summer or autumn season, milk-powder feedings, vaginal delivery, and duration of labor.48 It is virtually never seen in premature infants or those weighing <2500 g. There is no sexual or racial predilection.49 Congenital lesions can occur,50–52 but the majority of cases have their onset between 24 and 48 h of life. Lesions wax and wane, usually lasting a week or less, but cases lasting beyond 7 days have been reported. Occasionally very atypical presentations are seen (i.e. onset as late as 10 days of age) and pustules contain predominantly neutrophils,49,53 but such cases require careful evaluation and skin biopsy to exclude other causes.

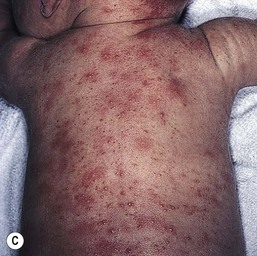

The classic eruption consists of barely elevated yellowish papules or pustules measuring 1–3 mm in diameter, with a surrounding irregular macular flare or wheal of erythema measuring 1–3 cm. The irregular shape of the flare has been likened to that of a flea bite (Figs 7.9A, 7.10![]() ). Although the characteristic lesions of erythema toxicum are usually discrete and scattered (Fig. 7.9B), extensive cases with either clusters of pustules, confluent papules, or pustules with surrounding erythema forming huge erythematous plaques can occur and be more difficult to diagnose (Fig. 7.9C). Lesions may appear first on the face and spread to the trunk and extremities, but may appear anywhere on the body except on the palms and soles.

). Although the characteristic lesions of erythema toxicum are usually discrete and scattered (Fig. 7.9B), extensive cases with either clusters of pustules, confluent papules, or pustules with surrounding erythema forming huge erythematous plaques can occur and be more difficult to diagnose (Fig. 7.9C). Lesions may appear first on the face and spread to the trunk and extremities, but may appear anywhere on the body except on the palms and soles.

Histologically, the lesions are eosinophilic pustules and characteristically intrafollicular, occurring subcorneally above the entry of the sebaceous duct.54 This follicular location explains the absence of lesions on the palms and soles. Peripheral eosinophilia has also been associated in a minority (about 15%) of cases.

The etiology of erythema toxicum is unknown: a graft-versus-host reaction against maternal lymphocytes has been postulated as a possible mechanism,55 but recent studies failed to show the presence of maternal cells in these lesions.56 Another theory proposes an immune response to microbial colonization through the hair follicles as early as 1 day of age.57 Immunohistochemical analysis of lesions from 1-day-old infants supports the accumulation and activation of immune cells in erythema toxicum lesions.58

A variety of inflammatory mediators such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-8, eotaxin, aquaporins 1 and 3, psoriasin, nitric oxide synthetases 1, 2 and 3, and HMGB-1 have been associated with erythema toxicum immunohistochemically.45,59 Tryptase-expressing mast cells (but not the cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide LL-37) have been located in erythema toxicum biopsy specimens.60

The diagnosis of erythema toxicum can usually be made by clinical appearance alone, but simple scraping of the pustule, smearing the contents onto a glass slide, and staining with Wright or Giemsa stain will reveal sheets of eosinophils with a few scattered neutrophils. Skin biopsy is rarely needed.

The differential diagnosis of erythema toxicum includes other pustular disorders of the newborn: infantile acropustulosis has a more acral rather than truncal distribution; herpes simplex has a more vesicular character, with subsequent crusting; staphylococcal impetigo has more well-developed pustules; congenital candidiasis has a positive KOH and can be more scaly. Transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) (see below) has primarily neutrophils in the infiltrate and is present at birth, and the pustules quickly disappear, leaving pigmented macules, but erythema toxicum and TNPM may appear together in some infants. Miliaria rubra can also present with erythematous papulopustules, but these favor the head and neck and are smaller lesions without the erythematous flare. No therapy is needed for erythema toxicum except for parental reassurance.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis

This disorder was first described in 1976,61 although it had undoubtedly occurred before that time. In fact, an abstract in 196162 is likely to give the first description of TNPM, which was then called ‘lentigines neonatorum.’ It occurs primarily in full-term African-descent infants in both sexes. In the 1976 report, 4.4% of African-American and 0.6% of Caucasian infants were affected.61 Lesions were always present at birth.

TNPM has three phases and hence three types of lesion. First, very superficial vesicopustules, ranging in size from 2 mm to as large as 10 mm, may be present in utero and are virtually always evident at birth (Fig. 7.11A). Because they are intracorneal and subcorneal, and thus very fragile, the pustules may be easily wiped away during the initial cleaning of the infant to remove vernix caseosa, so that the pustular phase may not be evident (Fig. 7.11B). The second phase is represented by a fine collarette of scale around the resolving pustule (Fig. 7.11C). The third phase consists of hyperpigmented brown macules at the site of previous pustulation (Fig. 7.11D). Although these macules have been called ‘lentigines’ (because of their resemblance to lentils), they are not true lentigines but appear to represent transient postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. They may last for up to several months before they fade. Some infants are born with these macules, the pustular phase having presumably occurred in utero. The most common location for TNPM has been under the chin, on the forehead, at the nape, and on the lower back and shins, although the face, trunk, palms, and soles are also affected.

The etiology of TNPM is unknown. However, some authors63,64 have postulated that TNPM is a precocious form of erythema toxicum neonatorum, with clinical and histologic overlap. They have proposed the term sterile transient neonatal pustulosis to describe this overlap entity.65 It is more likely, however, that these two conditions, which are both common, may coexist. In most infants there is little confusion based either on clinical appearance or time of onset.

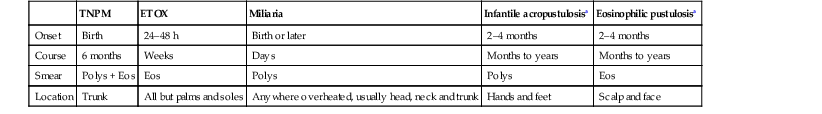

Smears of the contents of the pustules stained with Giemsa or Wright stain show predominantly neutrophils, although a few eosinophils have also been reported. A biopsy is rarely needed for diagnosis. Histologically, these lesions consist of subcorneal pustules filled with neutrophils, fibrin, and rare eosinophils.63 The differential diagnoses of transient benign pustular disorders in the neonate are summarized in Table 7.2. These benign conditions should be distinguished from neonatal staphylococcal infection, which would have a positive Giemsa stain on smear for polys and Gram-positive cocci and a positive bacterial culture, and for neonatal candidiasis, which would have a positive KOH examination for branching pseudohyphae and spores, as well as positive fungal cultures.

TABLE 7.2

The differential diagnoses of transient benign pustular disorders in the neonate

| TNPM | ETOX | Miliaria | Infantile acropustulosisa | Eosinophilic pustulosisa | |

| Onset | Birth | 24–48 h | Birth or later | 2–4 months | 2–4 months |

| Course | 6 months | Weeks | Days | Months to years | Months to years |

| Smear | Polys + Eos | Eos | Polys | Polys | Eos |

| Location | Trunk | All but palms and soles | Anywhere overheated, usually head, neck and trunk | Hands and feet | Scalp and face |

a See Chapter 10 for further discussion.

TNPM, transient neonatal pustular melanosis; ETOX, erythema toxicum.

Neonatal acne (cephalic pustulosis)

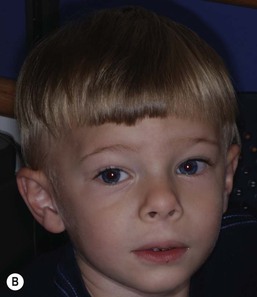

So-called neonatal acne (see Chapters 10 and 25) is one of the most common transient conditions in neonates and young infants. This condition is not truly a form of acne vulgaris, which has distinguishing features such as comedones and larger inflammatory papules and pustules (Figs 7.12, 7.13![]() ) (see Chapter 25). Instead it is characterized by smaller inflammatory papules and pustules more reminiscent of miliaria. The nosology and etiology of this common disorder are debated: is it a form of acne or another pustular disorder of infancy? The term ‘neonatal cephalic pustulosis’ has been proposed to replace the term neonatal acne, and both continue to be used. Neonatal acne may occur at birth but more typically appears within the first few weeks of life. Classically, neonatal acne has been described as inflammatory, erythematous papules and pustules, located primarily on the cheeks, but scattered over the face and often extending onto the scalp. Coexistence with fine scaling in the scalp and eyebrows also raise a relationship to seborrheic or atopic dermatitis (Fig. 7.14). In addition, clinical differentiation between neonatal acne and miliaria rubra may be impossible in some cases. Biopsies would aid in diagnosis, but they are not justified, as both conditions are benign and transient.

) (see Chapter 25). Instead it is characterized by smaller inflammatory papules and pustules more reminiscent of miliaria. The nosology and etiology of this common disorder are debated: is it a form of acne or another pustular disorder of infancy? The term ‘neonatal cephalic pustulosis’ has been proposed to replace the term neonatal acne, and both continue to be used. Neonatal acne may occur at birth but more typically appears within the first few weeks of life. Classically, neonatal acne has been described as inflammatory, erythematous papules and pustules, located primarily on the cheeks, but scattered over the face and often extending onto the scalp. Coexistence with fine scaling in the scalp and eyebrows also raise a relationship to seborrheic or atopic dermatitis (Fig. 7.14). In addition, clinical differentiation between neonatal acne and miliaria rubra may be impossible in some cases. Biopsies would aid in diagnosis, but they are not justified, as both conditions are benign and transient.

Comedones are absent. It has been hypothesized that this condition may represent an inflammatory reaction to Pityrosporum (Malassezia) species, both M. furfur and M. sympodialis. Treatment is usually not needed, however either an imidazole cream or low-potency topical corticosteroid, e.g. hydrocortisone 1%, may be useful in particularly severe cases.

Sucking blisters, erosions, pads, and calluses

Sucking blisters, erosions, and calluses on the hands and forearms are present at birth and can be solitary or bilateral.66 Although the primary lesion from sucking is usually a tense, fluid-filled blister on normal-appearing skin (Fig. 7.15), when the blister has ruptured an erosion may result. If the sucking has been less vigorous and more chronic, the lesion may become a callus. These lesions appear to result from repetitive vigorous sucking in utero at one particular site. Often when the neonate is presented after birth with the affected extremity, he/she will immediately demonstrate sucking behavior on that area. Sucking blisters on the extremities may be mistaken for other serious disorders such as herpes simplex, but their solitary, asymmetric nature and characteristic location should help to establish the correct diagnosis.

In infants who are vigorous suckers postnatally, sucking pads or calluses can also occur on the lips (Fig. 7.16 and see Fig. 27.9). These occur postnatally and should be differentiated from the lesions on the extremities. Sucking calluses appear on the mucosa caudal to the closure line of infants’ lips and are hyperkeratotic pads which eventually desquamate over 3–6 months.67,68 Histologically, there is epithelial hyperplasia and intracellular edema secondary to friction. No therapy is required.

Umbilical granuloma, patent urachus and omphalomesenteric duct remnant (umbilical polyp)

In some neonates, granulation tissue develops at the umbilical stump after the cord dries up and falls off, usually 6–8 days after birth. In most infants, the raw surface of the umbilicus heals within 12–15 days.69,70 Umbilical granulomata are grayish-pink papules on the umbilical stump (Figs 7.17![]() , 7.18). They are extremely friable and bleed easily on touching. They have a ‘velvety’ feel to the surface.

, 7.18). They are extremely friable and bleed easily on touching. They have a ‘velvety’ feel to the surface.

The etiology of umbilical granulomas is failure of the surface of the proximal portion of the cord to heal and subsequent proliferation of endothelial cells without atypia.71 The term granuloma is misleading, because these lesions are composed of proliferating endothelial cells, like pyogenic granulomas, and are not true granulomas.

The diagnosis is usually made clinically and confirmed with resolution with topically applied silver nitrate. However, it is important to distinguish umbilical granulomas from other embryonic remnants. The normal umbilical cord consists of two umbilical arteries, one umbilical vein, a rudimentary allantois attached to the bladder (urachus), and a remnant of the vitelline (omphalomesenteric duct) attached to the ileum.69 The proximal end of the vitelline duct creates Meckel’s diverticulum. A patent urachus will intermittently discharge urine. A persistent vitelline duct will have a malodorous discharge. An umbilical polyp is a distal remnant of the vitelline duct that creates an erythematous papule similar in appearance to an umbilical granuloma, but the surface is sticky because of mucus secreted from the intestinal mucosa (see Fig. 9.33);72 rarely, both remnants are present in the umbilical lesion.73 These developmental lesions all require surgical therapy. When talc-containing powders are used on the umbilical stump, talc granulomas can also form and look identical to umbilical granulomas.

The traditional treatment of umbilical granulomas is topical application of silver nitrate. Care must be taken to very lightly touch only the granulomas; otherwise chemical burns may occur on the surrounding normal skin.74 If lesions fail to respond to one or two treatments, then serious consideration should be given to alternative diagnoses. Most umbilical granulomas are seen and treated by pediatricians and rarely come to the attention of the dermatologist.

Color changes in the newborn (Box 7.1)

Pigmentary abnormalities resulting from abnormalities of melanin

Dermal melanosis (Mongolian spots)

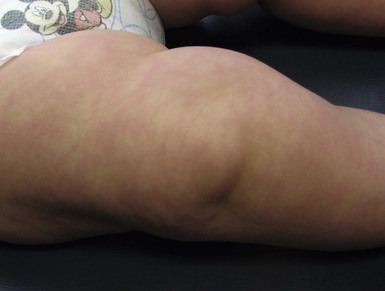

Mongolian spots are collections of melanocytes located in the dermis. They are macules or patches that may be solitary and measure a few millimeters, or multiple and several centimeters in size. They are a distinctive slate blue, gray, or black (Figs 7.19, 7.20, 7.21) and are most commonly located over the buttocks and sacrum, but often occur elsewhere.2,75 Over the buttocks, Mongolian spots are seen in up to 96% of African-American, 86% of Asian, 65% of Latino and 13% of Caucasian neonates. In the sacral location, they usually resolve over several years.

Similarly appearing dermal melanosis in other locations such as the arms and shoulders (nevus of Ito), around the cheek and eye, including the sclera (nevus of Ota),76 or elsewhere on the body (Fig. 7.22![]() ), may not resolve at all. The blue color of dermal melanosis is a result of the Tyndall effect, in which red wavelengths of light are absorbed and blue wavelengths are reflected back from the brown melanin pigment located deep in the dermis. The pathogenesis is postulated to be a defect in migration of pigmented neural crest cells, which usually reside at the dermoepidermal junction. Histologically, spindle-shaped melanocytes are dispersed within dermal collagen. No treatment is recommended for dermal melanosis. Extensive Mongolian spots have been described in infants with GM1 gangliosidosis (see Chapter 24) and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis (see Chapter 23).

), may not resolve at all. The blue color of dermal melanosis is a result of the Tyndall effect, in which red wavelengths of light are absorbed and blue wavelengths are reflected back from the brown melanin pigment located deep in the dermis. The pathogenesis is postulated to be a defect in migration of pigmented neural crest cells, which usually reside at the dermoepidermal junction. Histologically, spindle-shaped melanocytes are dispersed within dermal collagen. No treatment is recommended for dermal melanosis. Extensive Mongolian spots have been described in infants with GM1 gangliosidosis (see Chapter 24) and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis (see Chapter 23).

The pigmentation of nevus of Ota has been successfully treated with the Q-switched ruby laser.76,77 Small risks of melanoma and glaucoma exist for a nevus of Ota. It is most important to distinguish dermal melanosis from bruising, which would undergo a sequential color change from blue-black to green to yellow, so that there is no confusion about possible child abuse.

Transient epidermal hyperpigmentation

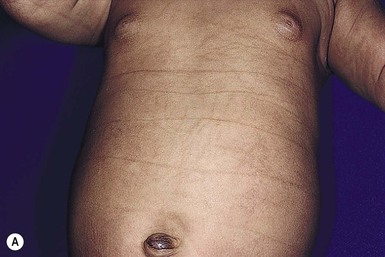

In more darkly pigmented neonates, transient, nearly black hyperpigmentation can be observed in the genital areas on the labia and scrotum (Fig. 7.23A,B), in a linear fashion on the lower abdomen (linea nigra), around the areolae, in the axillae, on the pinnae, and at the base of the fingernails (Fig. 7.23C).18 This is believed to be due to stimulation by melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) in utero, but the mechanism is unclear.

Other nonhormonal patterns of brown hyperpigmentation have also been reported. Horizontal bands of hyperpigmentation corresponding to creases in the abdomen (Fig. 7.24A) or on the back seem to reflect flexion in utero.78–80 They are transient and tend to fade within 6 months. They are thought to be a result of mechanical trauma from hyperkeratosis within the folds. Transient reticulated or linear pigmentation on the back and knees has also been reported (Fig. 7.24B),81 presumably as a result of post-traumatic hyperpigmentation in utero.

The most important differential diagnosis of the neonate with hormonally induced hyperpigmentation is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). In this life-threatening condition there is massive stimulation by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) resulting from an enzyme block in the synthesis of cortisol. The hyperpigmentation is believed to be due to cross-reactivity of ACTH with MSH receptors. Children with CAH also have ambiguous genitalia and will die if not promptly diagnosed and treated with replacement cortisol.

Transient hypopigmentation

African-American and Asian infants often have much lighter overall pigmentation in the newborn period, which gradually darkens over the first year of life. Generalized hypopigmentation is also seen in genetic conditions such as phenylketonuria (PKU), Menkes’ syndrome, Chediak–Higashi syndrome, and albinism. Non-transient but benign isolated hypopigmented macules and patches have been called nevus depigmentosus or, when in a segmental distribution, mosaic hypopigmentation. Such lesions can also be associated with genetic syndromes such as hypomelanosis of Ito and tuberous sclerosus (see Chapter 23).

Transient pigmentary changes not caused by melanin

Physiologic jaundice results from transient elevation of serum bilirubin, resulting in a generalized yellow discoloration of the skin in the first few days of life (Figs 7.25, 7.26![]() ). With jaundice, in contrast to carotenemia, which occurs later in infancy at age 1–2 years, there is yellow discoloration of the sclerae as well as the skin. Physiologic jaundice fades after the bilirubin returns to normal.

). With jaundice, in contrast to carotenemia, which occurs later in infancy at age 1–2 years, there is yellow discoloration of the sclerae as well as the skin. Physiologic jaundice fades after the bilirubin returns to normal.

Meconium staining often will darken the vernix caseosa but can also leave patchy, yellow-brown pigmentation, especially on desquamating epidermis.

Color changes resulting from vascular abnormalities

Cutaneous vasomotor instability

The ability of neonates to adjust to extrauterine surroundings is at first immature, and they can exhibit distinct cutaneous blood flow abnormalities. When neonates are cold, their constricted capillaries and venules may produce a reticulated, mottled, blanchable, violaceous pattern termed cutis marmorata (Figs 7.27, 7.28![]() ). Exposure to cold temperatures may also induce more vasoconstriction in acral than central areas of the body, resulting in deep violaceous to blue coloration of the hands, feet and lips, termed acrocyanosis (Fig. 7.29). Both of these conditions occur more often in premature infants. These transient conditions rapidly improve upon rewarming of the infant, and the tendency to occur diminishes with age. Cutis marmorata should not be confused with cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita, a vascular malformation that persists for several years and occurs in large, well-defined patches.

). Exposure to cold temperatures may also induce more vasoconstriction in acral than central areas of the body, resulting in deep violaceous to blue coloration of the hands, feet and lips, termed acrocyanosis (Fig. 7.29). Both of these conditions occur more often in premature infants. These transient conditions rapidly improve upon rewarming of the infant, and the tendency to occur diminishes with age. Cutis marmorata should not be confused with cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita, a vascular malformation that persists for several years and occurs in large, well-defined patches.

The so-called ‘harlequin’ color change is a rare physiologic phenomenon, whereby the amount of blood flow differs markedly on the right and left sides of the body, with a sharp cutoff at the midline.82,83 This is most often seen when a child is lying on one side, the dependent side exhibiting vasodilation and being strikingly redder than the upper half of the body (Fig. 7.30![]() ). The face and genitalia may be spared. Episodes last from seconds to minutes and are rapidly reversible with a change in position or increased activity. It is more common in premature infants, but can affect up to 10% of full-term babies. Its onset is at 2–5 days of age, and the phenomenon lasts up to 3 weeks. There is no pathologic significance.

). The face and genitalia may be spared. Episodes last from seconds to minutes and are rapidly reversible with a change in position or increased activity. It is more common in premature infants, but can affect up to 10% of full-term babies. Its onset is at 2–5 days of age, and the phenomenon lasts up to 3 weeks. There is no pathologic significance.

Rubor resulting from excessive hemoglobin

Because newborns have high levels of hemoglobin (16–18 g/dL) in the first weeks of life stimulated by in utero erythropoietin,84 there is generalized rubor, which fades as the hemoglobin physiologically drops to normal levels. Twin transfusion may occur in twins as a result of shunting of blood from one to the other, resulting in a major color difference at birth, reflecting a marked discrepancy in hemoglobin levels between the two infants.

Capillary ectasias (nevus simplex, salmon patch)

Erythematous macules and patches occurring over the occiput, eyelids, glabella, and, to a lesser extent, the nose and upper lip are minor vascular stains consisting of ectatic capillaries in the upper dermis with normal overlying skin (Figs 7.31, 7.32, 7.33–7.37). They occur in 70% of Caucasian, 68% of Latino, 59% of African-American, and 22% of Asian newborns,3 and have been given the common designations ‘angel’s kisses’ (eyelids) or ‘stork bites’ (nape) (Table 7.1). Most of the lesions resolve over several months to years (Figs 7.31, 7.38B), but 25–50% of nuchal lesions and a much smaller percentage of the glabellar lesions may persist into adult life. While the glabella, eyelids and nape are the most classic and characteristic locations for nevus simplex, more widespread involvement can be seen, including the vertex and occipital scalp, nose and perinasal skin, philtrum, lumbosacral skin and infrequently, the upper and mid-back. The more extensive form of nevus simplex is sometimes referred to as ‘nevus simplex complex’,85 the primary differential diagnosis of these benign transient lesions with the other true capillary malformations (port-wine stains also known as ‘nevus flammeus’), which do not resolve. These are usually more lateral in location and often continue to darken and thicken with age. The transient stains, particularly the glabellar ones, are often inherited as an autosomal dominant trait.

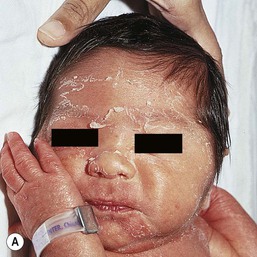

Vernix caseosa

Vernix caseosa is notable on the surface of the skin at birth as a chalky-white mixture of shed epithelial cells, sebum, and sometimes hair (Fig. 7.39). The vernix presumably serves as a lubricant to protect the infant skin from amniotic fluid. It enhances skin hydration and provides a natural barrier. Recent studies support its role in natural defense from microbes because it contains antimicrobial peptides and lipids.86 There is a marked difference in the biomarkers for structural proteins, cytokines and albumin during fetal maturation and its composition tends to favor wound healing and antimicrobial activity.87,88 It becomes thicker with advancing gestational age, although postmature infants usually have no vernix. In infants who have prepartum passage of meconium, the vernix may be stained yellow-brown, and this can be a clue to fetal distress.

Desquamation

Most full-term infants will have fine desquamation of the skin at 24–48 h of age. Premature infants do not show desquamation until 2–3 weeks of life. The postmature infant, however, is often born with cracking and peeling of the skin that is much greater in intensity than in full-term or premature infants (Fig. 7.40). The differential diagnosis of physiologic desquamation includes various forms of ichthyosis, as well as hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. These are discussed in detail in Chapters 19 and 29.

Access the full reference list at ExpertConsult.com ![]()

Figures 3, 5, 8, 10, 12, 13, 17, 19, 21, 22, 25–28, 30, 33–37 are available online at ExpertConsult.com