CHAPTER 50 Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion

Anterior lumbar fusion was first described by Muller in 1906.1 Evolutions of the technique have included modifications of the abdominal approach to a less invasive, mini-open technique and the use of interbody cages or structural allografts augmented with autogenous iliac crest graft, local bone graft, or, more recently, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP-2).2–5 Without the augmentation of posterior support, it has been well recognized that there is an increased rate of graft subsidence.1,6 The combination of anterior lumbar interbody fusion with a posterolateral instrumented fusion (360-degree fusion) has been shown to yield fusion rates of greater than 95%.7 Anterior lumbar interbody fusion has significant potential morbidities, however, including potential injury to the great vessels, abdominal hernia, injury to the sympathetic chain with subsequent sexual dysfunction, and thromboembolus secondary to retraction of the artery.8–10

Recognition of the biomechanical advantages of an anterior lumbar interbody fusion augmented with rigid posterior instrumentation led to the development of posterior-only approaches to the disc space to eliminate the approach-related morbidity of anterior interbody fusions. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion was developed to provide access to the disc space via a bilateral posterior approach with retraction of the thecal sac. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion is limited in its use to below the level of the conus, however, owing to the degree of thecal sac retraction necessary. Because of the retraction of the neural elements with posterior lumbar interbody fusion, there is concern for injury to the nerve roots, pain syndromes secondary to injury of the dorsal root ganglion, and cerebrospinal fluid leaks.11

Anterior lumbar interbody fusion via a transforaminal posterior approach (transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion [TLIF]) was first described by Harms and Rolinger in 1982.12 Using a transforaminal approach via osteotomy of the pars interarticularis and inferior articular facet allows for facile access to the disc space with minimal retraction of the neural elements, avoids the morbidity of an anterior approach,13,14 and has a lower complication rate than direct posterior lumbar interbody fusion.11 Accessing the disc space via a posterior annulotomy, approximately 56% of the endplate can be prepared for fusion15 with placement of bone graft and interbody implant. Combined with standard posterolateral instrumentation, decortication, and bone grafting, radiographic fusion rates greater than 90% can be achieved.16 Published outcomes of single-level TLIF and multilevel TLIF are equivalent or better than anterior and 360-degree fusions, with restoration of the disc space height.16,17 TLIF has been shown to result in significant savings relative to anteroposterior interbody fusion, owing in part to the decreased operating room time, less blood loss, and shorter hospital stays.18

Although some degree of restoration of disc space height with TLIF has been documented, the magnitude of restoration has been shown to be less than that achieved via anterior lumbar interbody fusion.19,20 Similarly, longitudinal studies have shown a progressive loss of restored lordosis, as the fusion construct over time tends to drift back to the preoperative sagittal balance. The clinical significance of radiographic differences between anterior lumbar interbody fusion and TLIF is unknown because these radiographic differences have not been shown to correlate to differences in outcome measures.20

Radiculopathy secondary to a foraminal disc herniation is difficult to address adequately from a midline approach and decompression owing to limited access to the lateral foramen. A far-lateral or foraminal disc herniation may be managed with a facetectomy, facilitating a transforaminal approach to the nerve root.21 TLIF may be considered as treatment for a foraminal disc herniation, particularly in the setting of significant loss of disc space height, because one may directly decompress the nerve root with the facetectomy, achieve an interbody and posterolateral fusion, and achieve indirect decompression with increase in the disc space height.

Advances in less invasive spine surgery, mini-open approaches, tubular retractors, and percutaneous instrumentation systems have been applied to TLIF, and minimally invasive TLIF procedures have been proposed to address the morbidity of the posterior midline approach. Preliminary studies have suggested that minimally invasive approaches may result in less blood loss and shorter hospital stays.22–24 These preliminary reports are case series, however, so the results must be extrapolated to general practice with caution. Prospective randomized studies are needed comparing less invasive or minimally invasive TLIF procedures with the standard open midline approach to compare clinical outcomes and radiologic indices (disc space height, graft placement, lordosis, and fusion).

Surgical Procedure

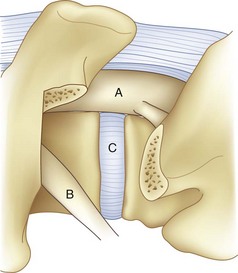

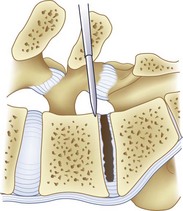

For transforaminal access to the disc space, it is necessary to remove the entire facet joint effectively on one side. This is accomplished by removing the inferior articular process of the cephalad level with an osteotomy through the pars interarticularis. This osteotomy should be performed on the side of greatest neural pathology; the osteotomy through the pars should be done as cephalad as possible to maximize the exposure but with care not to violate the pedicle itself (Fig. 50–1). Before the osteotomy, the ligamentum flavum should be completely freed from the lamina with a curet; particularly in the setting of a revision procedure, removal of the ligamentum and associated adhesions after the osteotomy may prove difficult and increase the risk of incidental durotomy. The transforaminal approach may be done either in concert with a midline laminectomy or with preservation of the spinous processes and midline ligamentous structures. To preserve the midline structures, one first makes the osteotomy up the medial aspect of the ipsilateral lamina, with the second osteotomy across the pars interarticularis as close as possible to the inferior margin of the cephalad pedicle. The inferior articular facet may be grasped with a Leksell rongeur or pituitary and rotated away from the underlying dura, taking care to remove any ligamentous adhesions with a curet.

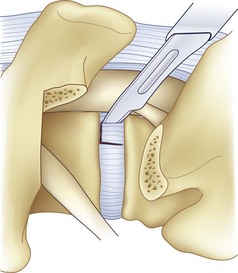

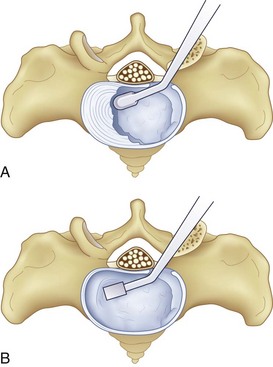

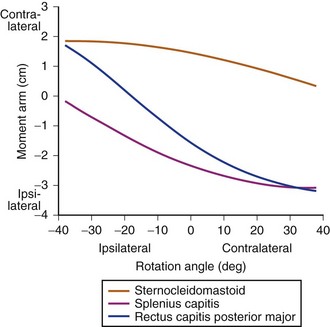

After completion of the surgical exposure of the transforaminal zone as described, a nerve root retractor should be placed medially to protect the thecal sac. With appropriate surgical exposure, only minimal retraction should be necessary as protection against incidental durotomy during the annulotomy. The posterior anulus should be incised widely with a box cut, with care taken to visualize the exiting and traversing nerve roots (Fig. 50–2). After completion of the annulotomy, the discectomy may be started with a pituitary rongeur and curets. A forward angled pituitary is necessary to enter the disc space on the contralateral side of the patient. When removing the disc and cartilage from the endplates, care must be taken not to violate the subchondral bone. Angled curets and chondrotomes should be used to remove the cartilaginous endplate from the far lateral side. A thorough discectomy and endplate preparation are essential, but absolute care must be taken not to violate the anterior anulus or subchondral bone (Fig. 50–3).

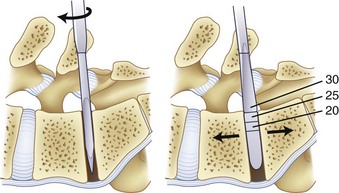

As the discectomy progresses, sequential dilation of the disc space should be accomplished with serial dilators. When impacting the dilators into the disc space, care must be taken to follow the sagittal plane of the interspace to avoid driving the dilator through the endplate, particularly in an osteoporotic patient (Fig. 50–4). If necessary, exposure may be aided by distracting between the spinous processes with a lamina spreader. After distraction, the assistant must hold the lamina spreader to stabilize it because inadvertent dislodgment may place the contents of the spinal canal at risk. The posterior lips of the vertebral bodies may be removed with osteotomes so that they are flush with the concavity of the endplate; if not removed, the interbody implant may be undersized (Fig. 50–5). After dilation to an appropriate size, the trial implant should be placed, with care taken to tamp it appropriately medial and anterior.

After implant trialing, the interspace should be bone grafted with the clinically indicated graft material. Bone graft should be placed into the anterior interspace and the implant. After anterior grafting of the interspace, the implant with graft is placed, and tamps are used to direct the implant anterior and medially (Fig. 50–6).

rhBMP-2 is currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in an anterior interbody cage but is not FDA approved for use in a posterior transforaminal interbody fusion. Several studies have investigated the off-label use of rhBMP-2 in TLIF, with published fusion rates similar to rates achieved with autograft bone in the cage. There have been reports of an increased incidence of radiculopathy postoperatively on the side of the transforaminal approach when rhBMP-2 is used, and an increased incidence of heterotopic bone formation has been noted.25 When rhBMP-2 is used posterolaterally, there have been reports of sterile seroma formation and local tissue swelling.26 Some investigators have hypothesized that rhBMP-2 may incite an inflammatory response along the nerve root if it leaks out of the intervertebral space, but this has not been confirmed. An increased incidence of transient vertebral body osteolysis has been noted27,28; it is hypothesized that with perforation of the endplate, the rhBMP-2 may incite a transient remodeling of the cancellous bone. The surgeon should take into consideration these reported complications when contemplating the use of rhBMP-2 in an “off-label” setting.

Although the transforaminal approach is advocated over a direct posterior approach to the intervertebral space in part because it necessitates comparatively less retraction of the thecal sac, there have been reports of postoperative radiculopathy on the ipsilateral side of the transforaminal approach. Some instances of radiculopathy may result from overly vigorous retraction of the exiting nerve root. There have been reports more recently of an increased incidence of radiculopathy when rhBMP-2 is used in the intervertebral space and incidences of heterotopic bone formation.25,29 This is an “off-label” use of rhBMP-2. This issue is significant, however, owing to the increasing use of biologics in spine surgery. It is hypothesized that biologics that upregulate the transforming growth factor pathway may promote an inflammatory response if they are introduced to the neural space. If the surgeon thinks it is clinically indicated to use a biologic osteoinductive promoter in the disc space, it may be advisable to consider strategies to minimize the possibility of migration from the disc space to the spinal canal and neural foramen.

There is some debate regarding the optimal position of the interbody graft. Harms and Rolinger12 originally described the procedure with a middle to posterior third graft position, to take advantage of the stronger posterolateral endplates. Subsequently, other authors have advocated a more anterior position of the interbody graft to improve its load-sharing properties and to facilitate restoration of lumbar lordotic angle.30 In disc space preparation and implant insertion, care must be taken to preserve the anterior anulus. Violation of the anterior anulus may result in inadvertent entry into the retroperitoneum with either an instrument or an implant, which may be catastrophic because of the nearby location of the large vessels. During preparation of the disc space, dilation, trialing, and implant insertion, the surgeon must maintain direct visualization of the working space. Intraoperative x-ray or fluoroscopic imaging should be used if there is any ambiguity regarding the position of instruments, implants, or the angle of the disc space. If there is a decline in hemodynamic status at any point after beginning disc space preparation, the potential of a vascular catastrophe must be considered.

Case Presentation

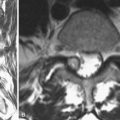

A 38-year-old woman who had a prior right-sided L4-5 microdiscectomy presented with recurrent right L5 radiculopathy and significant back pain (Fig. 50–6). She was managed initially with selective L5 root blocks and physical therapy without improvement. Plain films and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a recurrent right-sided L4-5 disc herniation and significant loss of disc space height at L4-5 with a new degenerative spondylolisthesis. Given the recurrent disc herniation and degeneration with spondylolisthesis of the L4-5 interspace, L4-5 TLIF was offered to stabilize the L4-5 interspace, restore the disc space height, and decompress the nerve root.

Complications

TLIF has a complication rate that is comparatively low relative to that of anteroposterior lumbar interbody fusion.14 For single-level TLIF, fusion rates are reported to be greater than 90%, but they are less than 90% for multilevel procedures. As with any procedure with pedicle screws, there is the possibility of screw misplacement; the incidence of a misplaced pedicle screw with TLIF procedure is approximately 5%.13 Transient postoperative neurologic deficit has been reported to range from 2% to 7%. Neurologic deficits lasting longer than 3 months were reported to occur in 4% of patients undergoing minimally invasive TLIF approaches in one series of 73 minimally invasive cases.14 In cases reported to have a postoperative radiculopathy, the most commonly affected nerve root is L5.16

Minor complications have been reported to occur in 16% of cases, with an approximately 5%/level risk of transient radiculopathy and 4%/level risk of incidental durotomy.13,16 One large series of 124 consecutive TLIF procedures (51 open, 73 minimally invasive) reported a 20% incidence of cerebrospinal fluid leak in the open cases.14 Postoperative infections have an incidence of approximately 5%.13,16 Postoperative hematomas have been reported to have an incidence of approximately 4%.14 In addition to postoperative radiculopathy on the ipsilateral side of transforaminal approach, there has also been a report of postoperative radiculopathy on the contralateral side,31 hypothesized to occur in the setting of asymptomatic contralateral stenosis that is exacerbated by the increased lordosis resulting from the procedure. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy has been reported postoperatively,16 presumably from irritation of the dorsal root ganglion. Postoperative gastrointestinal complications, predominantly ileus, were reported in 4% of patients in the series reported by Potter and colleagues16 of 100 TLIF procedures; one patient developed pseudomembranous colitis.

Summary

Key Points

1 Javernick MA, Kuklo TR, Polly DWJr. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: Unilateral versus bilateral disc removal—an in vivo study. Am J Orthop. 2003;32:344-348.

2 Potter BK, Freedman BA, Verwiebe EG, et al. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: Clinical and radiographic results and complications in 100 consecutive patients. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:337-346.

3 Kwon BK, Berta S, Daffner SD, et al. Radiographic analysis of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:469-476.

4 Whitecloud TS3rd, Roesch WW, Ricciardi JE. Transforaminal interbody fusion versus anterior-posterior interbody fusion of the lumbar spine: A financial analysis. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:100-103.

5 Villavicencio AT, Burneikiene S, Bulsara KR, et al. Perioperative complications in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion versus anterior-posterior reconstruction for lumbar disc degeneration and instability. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:92-97.

1 Resnick DK. Lumbar interbody fusion: Current status. Neurosurg Q. 2008;18:77-82.

2 Burkus JK, Heim SE, Gornet MF, et al. Is INFUSE bone graft superior to autograft bone? An integrated analysis of clinical trials using the LT-CAGE lumbar tapered fusion device. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:113-122.

3 Burkus JK, Dorchak JD, Sanders DL. Radiographic assessment of interbody fusion using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein type 2. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:372-377.

4 Burkus JK, Heim SE, Gornet MF, et al. The effectiveness of rhBMP-2 in replacing autograft: An integrated analysis of three human spine studies. Orthopedics. 2004;27:723-728.

5 Mummaneni PV, Pan J, Haid RW, et al. Contribution of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to the rapid creation of interbody fusion when used in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: A preliminary report. Invited submission from the Joint Section Meeting on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves, March 2004. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1:19-23.

6 Dennis S, Watkins R, Landaker S, et al. Comparison of disc space heights after anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989;14:876-878.

7 Kwon BK, Hilibrand AS, Malloy K, et al. A critical analysis of the literature regarding surgical approach and outcome for adult low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(Suppl):S30-S40.

8 Kulkarni SS, Lowery GL, Ross RE, et al. Arterial complications following anterior lumbar interbody fusion: Report of eight cases. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:48-54.

9 Johnson RM, McGuire EJ. Urogenital complications of anterior approaches to the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981:114-118.

10 Sasso RC, Kenneth Burkus J, LeHuec JC. Retrograde ejaculation after anterior lumbar interbody fusion: Transperitoneal versus retroperitoneal exposure. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:1023-1026.

11 Humphreys SC, Hodges SD, Patwardhan AG, et al. Comparison of posterior and transforaminal approaches to lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:567-571.

12 Harms J, Rolinger H. [A one-stager procedure in operative treatment of spondylolistheses: dorsal traction-reposition and anterior fusion (author’s transl)]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1982;120:343-347.

13 Hee HT, Castro FPJr, Majd ME, et al. Anterior/posterior lumbar fusion versus transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: Analysis of complications and predictive factors. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:533-540.

14 Villavicencio AT, Burneikiene S, Bulsara KR, et al. Perioperative complications in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion versus anterior-posterior reconstruction for lumbar disc degeneration and instability. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:92-97.

15 Javernick MA, Kuklo TR, Polly DWJr. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: Unilateral versus bilateral disk removal—an in vivo study. Am J Orthop. 2003;32:344-348. discussion 348

16 Potter BK, Freedman BA, Verwiebe EG, et al. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: Clinical and radiographic results and complications in 100 consecutive patients. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:337-346.

17 Hackenberg L, Halm H, Bullmann V, et al. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: A safe technique with satisfactory three to five year results. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:551-558.

18 Whitecloud TS3rd, Roesch WW, Ricciardi JE. Transforaminal interbody fusion versus anterior-posterior interbody fusion of the lumbar spine: A financial analysis. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:100-103.

19 Hsieh PC, Koski TR, O’Shaughnessy BA, et al. Anterior lumbar interbody fusion in comparison with transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: Implications for the restoration of foraminal height, local disc angle, lumbar lordosis, and sagittal balance. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:379-386.

20 Kim JS, Kang BU, Lee SH, et al. Mini-transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion versus anterior lumbar interbody fusion augmented by percutaneous pedicle screw fixation: A comparison of surgical outcomes in adult low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22:114-121.

21 Epstein NE. Foraminal and far lateral lumbar disc herniations: Surgical alternatives and outcome measures. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:491-500.

22 Schizas C, Tzinieris N, Tsiridis E, et al. Minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: Evaluating initial experience. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1683-1688.

23 Dhall SS, Wang MY, Mummaneni PV. Clinical and radiographic comparison of mini-open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in 42 patients with long-term follow-up. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:560-565.

24 Park P, Foley KT. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with reduction of spondylolisthesis: Technique and outcomes after a minimum of 2 years’ follow-up. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:E16.

25 Joseph V, Rampersaud YR. Heterotopic bone formation with the use of rhBMP2 in posterior minimal access interbody fusion: A CT analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:2885-2890.

26 Bridwell KH, Anderson PA, Boden SD, et al. What’s new in spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1654-1663.

27 Lewandrowski KU, Nanson C, Calderon R. Vertebral osteolysis after posterior interbody lumbar fusion with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2: A report of five cases. Spine J. 2007;7:609-614.

28 McClellan JW, Mulconrey DS, Forbes RJ, et al. Vertebral bone resorption after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP-2). J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:483-486.

29 Wong DA, Kumar A, Jatana S, et al. Neurologic impairment from ectopic bone in the lumbar canal: A potential complication of off-label PLIF/TLIF use of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2). Spine J. 2008;8:1011-1018.

30 Kwon BK, Berta S, Daffner SD, et al. Radiographic analysis of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:469-476.

31 Hunt T, Shen FH, Shaffrey CI, et al. Contralateral radiculopathy after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(Suppl 3):311-314.