41 Transesophageal Echocardiography

Training and Certification

The introduction of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) into the perioperative arena in the mid-1980s heralded a new era in the care of surgical patients and offered a new dimension to the role of anesthesiologists.1 Soon after its introduction, it became clear that perioperative TEE had the potential for significant impact on the care for both cardiac and noncardiac surgical patients.2–4 Because of its minimally invasive nature and a high diagnostic potential, TEE has been used by practitioners from multiple specialties, for example, cardiologists, anesthesiologists, and critical care physicians. The therapeutic impact of TEE on preoperative surgical decision making soon was established, and it was recognized that it has the potential to offer improvements in patient care and, perhaps, eventual improvements in outcomes. However, there is the possibility for patient harm from misdiagnosis or from a poor understanding of the limitations of the technology and its application. The introduction of any new technology or technique into clinical practice, which can have such a dramatic impact on patient management, requires proper training and experience. The effectiveness of this expertise should be demonstrable by, among other things, significant training and experience, objective and validated measurement tools such as examinations, and demonstration of continued clinical activity. It was from these basic principles that the development of a certification process for perioperative TEE was born.

The debate surrounding the credentialing and certification for TEE is not unique to this technology. Often, the introduction and acceptance of technology into clinical practice outpace the efforts to legislate the credentialing requirements. Several other clinical techniques (e.g., laparoscopic surgical techniques and percutaneous angioplasty) were widely adopted clinically before credentialing and certification could be established.5 Perioperative TEE also has been rapidly accepted and deployed as an essential monitor in the cardiac operating rooms (ORs) before training and certification guidelines could be adequately developed. Despite being in clinical practice for more than two decades, a survey conducted among the membership of the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (SCA) in 2001 showed that of the nearly 2000 members, less than 30% had any formalized training in TEE, and less than 50% reported having any specific credentialing requirements at their hospitals.6 Although there have been considerable improvements in perioperative TEE training programs, there is considerable room for improvement, and the majority of the clinical institutions, which include major academic centers, do not have specific credentialing requirements for anesthesiologists to use this monitoring modality.

The importance of collaboration between anesthesiologists and cardiologists was acknowledged in the 1996 American Society of Anesthesiologists/Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (ASA/SCA) guidelines for training and certification in TEE.5,7 It was believed that because it was impractical for cardiologists to be present in the OR all the time, it was imperative for anesthesiologists to learn to perform and interpret intraoperative TEE examinations. To encourage more widespread use of TEE, the guidelines also stated that TEE should not be performed for making extremely focused examinations and narrow diagnoses, but broadly as a monitor to assist in cardiac surgical procedures. In addition to specifically describing the evidence of the therapeutic utility of TEE in clinical situations, the indications were analyzed in the context of the patient, the procedure, and the clinical setting7 (Boxes 41-1 and 41-2). The ASA/SCA guidelines recommended the following fundamental principles for optimal physician training in perioperative TEE5,7:

BOX 41-1 Indications for Transesophageal Echocardiography

From Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography. Anesthesiology 84:986–1006, 1996.

BOX 41-2 Cognitive Requirements for Perioperative Transesophageal Echocardiography

Adapted from Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography. Anesthesiology 84:986–1006, 1996.

Basic Training

Cognitive Skills

Technical Skills

Advanced Training

Cognitive Skills

Technical Skills

Definitions

Perioperative Echocardiography

According to current guidelines, perioperative echocardiography is defined as TEE, epicardial, or epiaortic echocardiography performed on surgical patients immediately before, during, or after surgery.7,8 Transthoracic echocardiography, although sometimes performed on surgical patients, is not considered a “perioperative” technique. Thus, the guidelines do not apply to transthoracic echocardiography–related procedures and image acquisition techniques.

Basic Training

At the basic level of training, the trainee should have knowledge of the principles of ultrasound and image acquisition, be able to place a TEE probe, operate the equipment, and conduct an examination. Although independent work is expected, all examinations performed by the basic-level trainee have to be supervised and interpreted under the guidance of an advanced-level echocardiographer together with the availability of a periodic assessment program. It also was recommended that anesthesiologists trained as basic echocardiographers should be able to use the TEE for establishing diagnoses within the customary practice of anesthesiology7 (Box 41-3).

BOX 41-3 Basic and Advanced Level Echocardiographer

From Cahalan MK, Abel M, Goldman M, et al: American Society of Echocardiography and Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists task force guidelines for training in perioperative echocardiography. Anesth Analg 94:1384–1388, 2002.

| Basic | Advanced | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum number of examinations | 150 | 300 |

| Minimum number personally performed | 50 | 150 |

| Program director qualifications | Advanced perioperative echocardiography training | Advanced perioperative echocardiography training plus at least 150 additional perioperative TEE examinations |

| Program qualifications | Wide variety of perioperative applications of echocardiography | Full spectrum of perioperative applications of echocardiography |

Advanced Training

An advanced-level trainee should have performed at least 300 comprehensive TEE examinations under supervision; in addition, the trainee should have performed 150 examinations independently. The training has to be comprehensive and broad-based with a significant component of independent activities. Such a training process should have a formal and informal evaluation program as well. Furthermore, the echocardiographic examinations performed during basic training can be counted toward completion of advanced training. An anesthesiologist who has advanced TEE training should be able to use TEE to its full diagnostic potential and use it for establishing diagnoses that can possibly impact the planned surgical procedure7 (see Box 41-3).

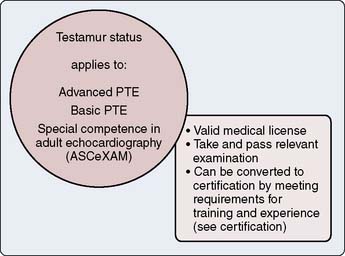

Testamur Status

A testamur status is achieved by demonstration of a passing grade in the examination of special competence in perioperative TEE administered by the National Board of Echocardiography (NBE).2 For those physicians who cannot be certified to be advanced examiners (explained later), testamur status can be maintained indefinitely (Figure 41-1).

Certification/Diplomate Status

The certification process of the NBE consists of:

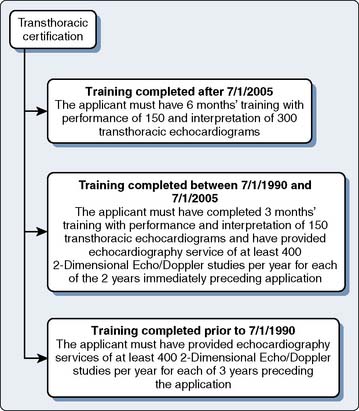

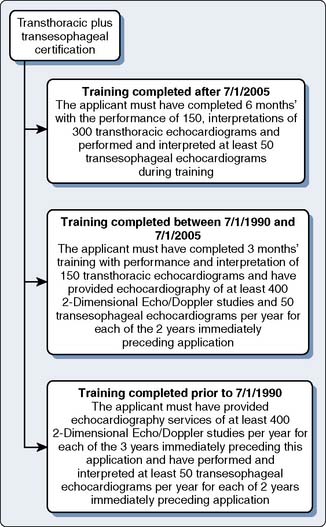

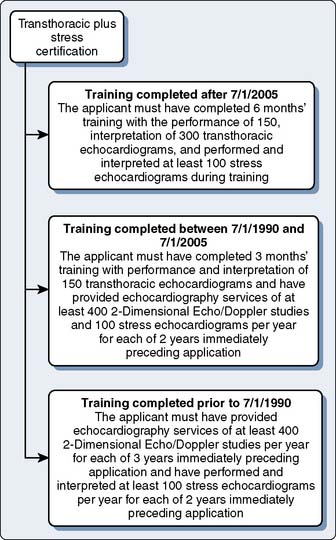

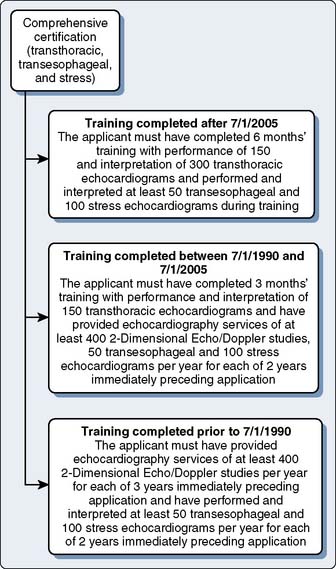

The basic and advanced TEE certifications are discussed in greater detail later in the chapter (Figures 41-2 and 41-3). The certification process of the NBE encompasses not only TEE-related training and experience, but has been applied to transthoracic echocardiography and stress echocardiography (Figures 41-4 to 41-7).

Perioperative transesophageal echocardiography training

Since its introduction, there has been considerable controversy about the level of training required to be proficient and competent in performing perioperative TEE. Introduction and ready acceptance of TEE in the cardiac ORs led to a situation in which TEE had to be adopted by anesthesiologists who had already finished their training. They not only had to train themselves by “on-the-job” experience, but had to develop training guidelines for in-training residents and fellows. Because of the lack of a specific testing mechanism, the expertise was established by demonstration of exposure to a specific number of TEE examinations. There was significant debate about the optimum time/number of examinations required to gain adequate training to be a “competent examiner”—that is, the duration of specific training period versus its comprehensiveness and the total number of examinations versus the variety of pathologies examined.9,10 As a result of the aforementioned factors, the requirements for adequate training were initially purposely kept flexible to accommodate different levels of experience of practitioners. Also, the requirements were made less binding and restrictive to accommodate different levels of experience and exposure to echocardiography. It was believed that rather than specifying the number of months or examinations performed, it was equally important that anesthesiologists should have broad-based training in perioperative echocardiography with exposure to a wide variety of cases.8

Evolution of Training Guidelines

The training guidelines for echocardiography have evolved over time from time-limited experience requirements to achieve an incremental expertise in echocardiography from Level I to III11–13 to the present situation, when use of TEE is being encouraged for all anesthesiologists (cardiac and noncardiac), and there are suggestions to include TEE education as part of the core anesthesia residency training. Over time, the increasing utilization of intraoperative TEE has led to a blurring of specialty lines with anesthesiologists assuming a greater role in performing TEE examinations in the perioperative period, a task originally performed by cardiologists. With the redefined role of anesthesiologists as the “perioperative echocardiographers,” the ASA/SCA published their own specific recommendations for perioperative echocardiography for anesthesiologists already using TEE. These guidelines laid down not only the indications and contraindications but also the necessary cognitive and technical skills required to perform a perioperative TEE examination7 (see Boxes 41-1 and 41-2). Furthermore, rather than defining the expertise of the echocardiographers as Level I, II, or III examiners, as in earlier guidelines, the terms basic- and advanced-level examiners were used (see Box 41-3). A basic-level echocardiographer is defined as a physician capable of making a decision as to when and how to perform a TEE examination, whereas an advanced-level examiner is someone capable of making independent decisions based on TEE findings, which can potentially change the course of the procedure (see Box 41-3). Because there was a lack of specific training programs for anesthesiologists to acquire TEE skills, the guidelines recommended commercially available educational materials, workshops, and mentorship from experienced echocardiographers to gain expertise.

After considerable thought and deliberation, the initial ASA/SCA practice guidelines were further updated by the ASA/SCA in 2002.8 Whereas the initial guidelines recommended only establishment of training programs,7 the updated document described the specifics of the training program environment, program director’s qualifications, and mandated the inclusion of TEE training in the established cardiac anesthesia fellowship programs. It was also recommended that, over time, as in cardiology residency programs, specific TEE training fellowships also should be established for anesthesiologists.8 Furthermore, in the revised guidelines, epiaortic and epivascular echocardiography examinations also were included as perioperative echocardiography techniques. The updated guidelines have recommended a total of 150 completed TEE examinations, of which 50 are to be performed personally for basic-level trainees, and a total of 300 TEE examinations, of which 150 are to be performed personally for an advanced trainee.8 Later, the recommendations made by the ASA/SCA updated guidelines (see Box 41-3)8 also were adopted by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) clinical competency statement on echocardiography.14–16

In 2006, the Canadian Society of Echocardiography and the Cardiovascular Section of the Canadian Society of Anesthesiologists comprehensively defined the roles of basic and advanced echocardiographers, as well as the training program requirements for basic- and advanced-level echocardiographers.17,18 These guidelines extended the training requirements and expectations of the diagnostic potential laid out in the ASA/SCA guidelines of 20028 for different levels of examiners. A qualified director of a training program in perioperative echocardiography, the training program environment, availability of resources, and the presence of a continuing medical education program also were mentioned as necessary ingredients for an echocardiography training environment.17,18 The Canadian guidelines have gone a step further and, in addition to the type of echocardiographic examination, also have identified specific diagnoses expected from basic- and advanced-level examiners. This is significant progress in being more specific as compared with the initial ASA/SCA guidelines,8 in which only broad expectations were laid down of the depth and comprehensiveness of a perioperative TEE examination from basic- and advanced-level examiners. The Canadian guidelines, however, have increased the expected number of examinations personally performed and interpreted by the trainees (100 for the basic-level and 200 for an advanced-level trainee).17,18 These TEE studies also may include examinations performed outside the OR in the intensive care unit. Furthermore, these guidelines also have set a time limit of 1 year to complete these TEE training requirements.17,18

It is obvious from the earlier discussion that the training expectations and requirements have and will continue to evolve as the technology improves. Equipment costs and lack of training opportunities have been the major impediments to the widespread acceptance and use of this technology in cardiac and noncardiac surgery.19 The invasive nature of TEE, cumbersome credentialing, and licensing requirements also preclude a “hands-on” experience at continuing medical education workshops and observership-based training programs. Although anesthesia residents are expected to have an introduction to the basic TEE examination during their accredited training, it is a not a mandated part of the anesthesia residency curriculum. Since the accreditation of cardiac anesthesia fellowship programs, TEE training has been formalized with months dedicated to intraoperative echocardiography. The inclusion of TEE as part of an accredited cardiac anesthesia fellowship is the first step toward standardization of training in perioperative echocardiography. Over the next few years, the expectations are likely to change dramatically, and expertise in perioperative echocardiography probably will be considered a core competency in a cardiac anesthesia fellowship.

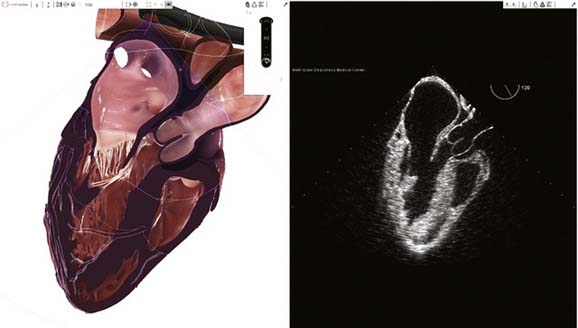

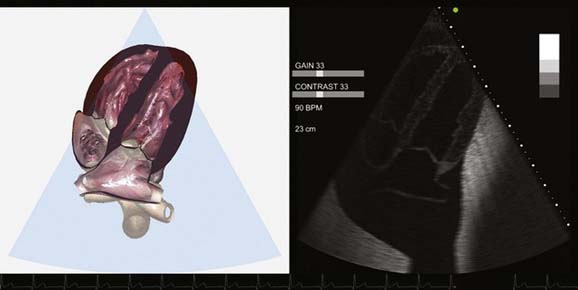

Training with Transesophageal Echocardiography Simulators

Over the years, many technologic advances have been tried to bridge the gap between the patient and virtual reality. Simulation is becoming a particularly attractive training method for techniques that require manual dexterity. Although simulation is an established technique of learning in the health care industry, no simulator was available for TEE training until recently.20 The complexity of cardiac structure, valvular function, and synchronization of a real TEE probe with a virtual model of the heart made such an endeavor cost-ineffective or prohibitive. As a result of many technologic breakthroughs and collaborative efforts of physicians, software engineers, and special-effects professionals, a TEE simulator was made available for commercial use in 2008 (Figure 41-8). As a result of this innovation, it is now possible to learn the basic TEE examination outside the OR with a TEE simulator and reduce the initial learning curve.20 Currently, the simulation technology consists of normal cardiac anatomy and physiology only, and disease states cannot be simulated anatomically or physiologically (Figure 41-9). At the current rate of technology development, it may soon be possible to learn “normal” anatomy, physiology, probe manipulations, and image orientation techniques on a TEE simulator, while concentrating on “abnormal” in the OR. This methodology of learning has the potential to significantly improve TEE training and education for the anesthesia residents of the future. However, the TEE simulator is quite expensive and is available for training in only a few major academic centers in the United States.

Recently, another simulator was introduced by Vimedix that has the capability of performing transthoracic and TEE examinations on a three-dimensional solid model of the heart (Figure 41-10). The simulator also is capable of Doppler interrogation and hemodynamic calculations. In addition, this simulator has the ability to simulate pathologic processes—for example, pericardial tamponade, biventricular systolic dysfunction, and valvular abnormalities (Figure 41-11). The availability of simulated abnormalities can revolutionize the training process and opens the door for novel methods of training and standardized testing.

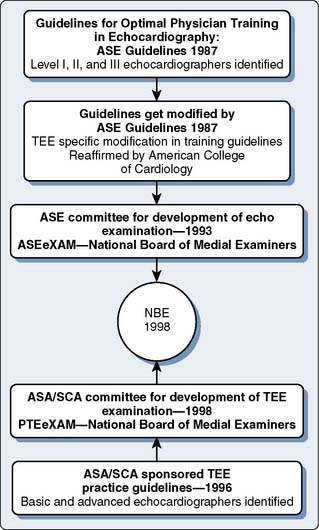

History of the development of the certification process

In 1987, the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) published its first recommendations on the knowledge, nature, and experience, as well as the type of training site, that were deemed as optimal for training physicians as echocardiographers11 (see Figure 41-12). In this publication, the ASE identified three levels of training: basic training, advanced training, and director of echocardiographic laboratory training. Basic training (Level I) was an introductory phase that did not aim to allow for independent performance or interpretation of echocardiographic examinations. Advanced training (Level II) sought to develop the knowledge and skills that would allow for independent practice under the supervision of a laboratory director. Echocardiographic laboratory director training (Level III) sought to prepare the physician to supervise others and to perform specialized echocardiographic procedures, which included perioperative TEE. For each level, requirements for the duration of training and the number of examinations performed and interpreted were set. As discussed earlier, though somewhat altered, this theme of levels in training, knowledge base, and expectations has persisted through the current model of certification. In 1992, the ASE modified these recommendations to relate specifically to TEE, and in 1995, the ACC reaffirmed them.12,13

In 1993, in addition to establishing recommendations for training, the ASE appointed a committee to develop and administer an examination in echocardiography that would be known as the ASEeXAM. Furthermore, an entity known as ASEeXAM, Inc. was established as a separate tax-exempt corporation independent from the ASE to avoid a conflict of interest. The primary objective of the examination was to “provide practicing echocardiographers the opportunity to demonstrate special competence in echocardiography.”21 Its other objectives were to set a standard for a knowledge base related to echocardiography, to stimulate continuing education, and to attempt to identify weaknesses and deficiencies in training. The National Board of Medical Examiners was chosen by the ASE to help develop an objective and valid test. The content of the examination consisted of multiple-choice questions covering the topics of physical principles, instrumentation, valvular heart disease, chamber size and function, congenital heart disease, and a few other miscellaneous subjects. Perioperative TEE was represented only as a small subtopic. After a field test in 1995, the first operational ASEeXAM was administered in 1996. The test was available to all licensed physicians regardless of field of expertise. Only 21 of the 373 examinees who took this examination (6%) were anesthesiologists. The pass rate was only 59% for all examinees and only 43% among anesthesiologists. Those who passed the examination were given the status of “testamur.”21

In 1995, following the lead of the ASE, the SCA created its own task force to develop an examination that focused on perioperative TEE (PTE). The SCA was, to some degree, motivated by the concern that the ASEeXAM format functionally excluded anesthesiologists from demonstrating their proficiency in PTE.5 The SCA also decided to hire the National Board of Medical Examiners to help develop and validate the test. The test was called the PTEeXAM and was administered for the first time in 1998. The examination was open to all licensed physicians, but actual examinees were almost exclusively anesthesiologists. The pass rate on the first examination was 76%.22 As with the ASEeXAM, examinees who passed were given the status of “testamur.” In 1996, the ASA and SCA published guidelines relating to the practice of TEE.7 These guidelines served mainly to establish recommendations concerning the appropriate indications for and the contraindications against performing TEE. No recommendations were made as to the duration of training or specific amounts of experience needed to reach either of these levels. At that time, the ASA/SCA committee lacked a consensus as to the best training pathway for PTE within the realm of anesthesiology.

During the process of developing examinations and training guidelines, the leadership of the SCA and ASEeXAM, Inc. had discussions regarding their parallel processes. There was justifiable concern on both sides that their two examinations would end up competing with one another, and that this would lead to confusion on the part of echocardiographers, hospital administrators, and third-party payers. Furthermore, if some sort of merger could be arranged that would satisfy the goals of both groups, administrative and other efficiencies could lead to significant cost savings. An agreement was reached and in December 1998, ASEeXAM Inc. was renamed the National Board of Echocardiography (NBE).2 The Board of Directors of the NBE was structured to include nine directors, three of whom were cardiac anesthesiologists. The board was given the responsibility of overseeing two separate examination committees. One committee was given the charge of maintaining the ASEeXAM, whereas the other oversaw the PTE examination. In 1999, the NBE administered its first pair of examinations. The ASEeXAM was changed to the ASCeXAM.

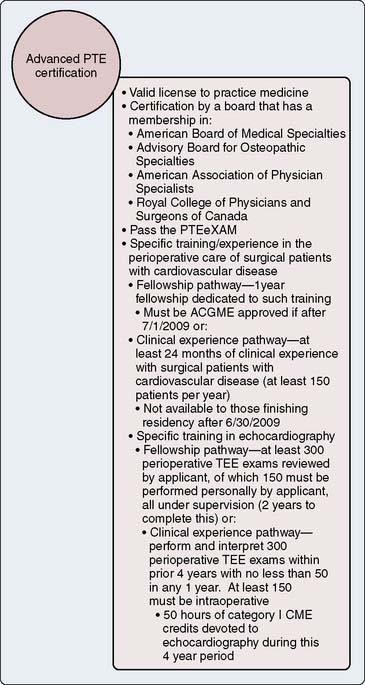

Certification

After several years of administering these examinations, the NBE next sought to address the issue of offering NBE certification (Figure 41-12). Certification combined successful completion of an NBE examination with the passing of set thresholds related to actual echocardiographic experience or training, or both. These requirements are demonstrated in Figures 41-2 and 41-3. Certification for the ASCeXAM began in 2001 and was based on the experience criteria developed by the ASE and ACC in the early to mid 1990s (see Figures 41-2 to 41-5). As mentioned earlier, the 1996 ASA/SCA task force did not develop thresholds for experience to distinguish between basic and advanced PTE. In 2002, a task force of SCA and ASE members developed these criteria.8 This allowed for certification centered around the PTEeXAM in 2004. Physicians who successfully met the requirements for certification were given the status of “diplomate.” Both the “diplomate” and “testamur” statuses are time-limited statuses and are valid for 10 years from the date of successful completion of the appropriate examination. The first recertification examination for the ASCeXAM was offered in 2005, and first ecertification for the PTEeXAM was given in 2007.

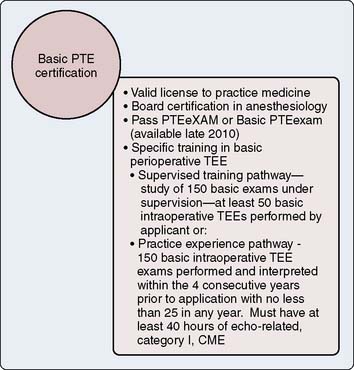

Basic Certification

In 2010, the NBE offered the first examination on basic PTE and first certification in basic PTE. The development of the basic PTE pathway was done in direct cooperation with the ASA. With the addition of the basic pathway, the former PTEeXAM pathway has now become the advanced PTEeXAM. The development of the basic PTE pathway was developed from the 2002 ASA/SCA guidelines discussed previously.8 The basic PTE pathway is meant to demonstrate competence for anesthesiologists who use TEE as a monitor during anesthesia. This pathway does not provide a measure of competence for the use of TEE as a diagnostic tool to affect the conduct of surgical procedures because this is an advanced skill.

Clinical competence versus certification

Clinical Experience versus Testing

Even before the institution of an official ASCeXAM21 and the PTEeXAM22 by the ASE, it had been demonstrated that experienced echocardiographers performed better on a multiple-choice examination than less experienced practitioners.23 It was recommended by the society that such tests could be used for periodic quality-assurance programs. Because most training guidelines recommend a specific number of cases to be performed to achieve a certain level, they do not account for individual rates of learning and case-mix variations in a particular program. Therefore, it was recommended that an achievement-based testing system rather than a numerical number of cases should determine the competency to perform perioperative TEE.23 There is no requirement by the NBE to document actual performance of perioperative TEE as a prerequisite to take the PTEeXAM. Therefore, it is quite possible that individuals may be able to pass the examination without any significant hands-on experience and, thus, may be construed as “experts” without the necessary experience.24 It also has been suggested that the PTEeXAM should be offered only to physicians who are actually performing perioperative TEE examinations.

Clinical Competence and Testamur Status

The requirements of the NBE for different examinations and certification application are freely available on their website (http://www.echoboards.org/). Although the American Board of Anesthesiology governs the certification process for anesthesiologists, it has never sought to require certification of individual techniques within the scope of the practice.7 It was recommended in the initial guidelines that if the certification in preoperative TEE was to be pursued, it should be done through a collaborative and a multidisciplinary process. Although the NBE examination has been administered for more than a decade, a passing score on the examination is not a requisite for demonstration of competence in clinical echocardiography by the ASA/SCA and AHA/ACC guidelines.8,14–16 Similarly, a considerable number of practitioners use TEE at an advanced level but have not gone through the NBE examination process. A mandatory requirement to demonstrate a passing grade on this examination for competence in echocardiography could also possibly have excluded these experienced and advanced examiners from performing perioperative TEE examinations. Achievement of a passing grade on the PTEeXAM does not imply that the practitioner has achieved the necessary technical skills to perform preoperative TEE examinations independently and, therefore, should not be used to substitute for clinical experience.18

Basic Certification

To circumvent the exclusionary effects of a restrictive policy and to promote the use of TEE by general anesthesiologists, the NBE also has offered a basic-level certification in perioperative echocardiography (see Figure 41-2). In this effort, the NBE has recognized that there may be a significant number of practitioners who may not be taking the PTEeXAM because they are not performing enough perioperative TEE examinations to satisfy the NBE requirement to be certified. Basic certification, as offered by the NBE, implies the ability to use the TEE for nondiagnostic monitoring purposes, especially during life-threatening emergencies. The ASA and SCA also have begun a joint initiative to conduct “basic echocardiography” courses throughout the year and at major annual meetings to introduce TEE to general anesthesiologists. These introductory courses and workshops are geared toward basic-level echocardiographers and are designed to enable a basic understanding of the principles of echocardiography. After 2 years of this initiative, the first basic certification examination was held in 2010.

The current requirements for advanced certification have a grandfather clause, that is, the practice experience pathway, to offer certification via the practice experience pathway for physicians who graduated before 2009. This is another opportunity for practitioners who are not formally trained, but perform TEE regularly, to become certified after passing the PTEeXAM. In addition to obtaining a passing score on the PTEeXAM, the practice experience pathway requires demonstration of continued clinical activity and involvement in care of patients with cardiovascular disorders. The Canadian guidelines actually have mandated the demonstration of a passing grade on the PTEeXAM to qualify to be classified even as a basic-level echocardiograher, and passing the examination is considered the first step in becoming an echocardiographer.18 It is obvious that the training and certification processes in perioperative echocardiography are in evolution. The accredited cardiac anesthesia fellowship programs have incorporated dedicated months of TEE training in their curriculum. Unlike cardiology, no fellowship programs are dedicated to perioperative echocardiography.

Maintenance of Certification

The testamur and the certification diplomas given by the NBE are time-limited, and although not mandated, a recertification examination is strongly encouraged by the NBE. The current guidelines recommend 50 comprehensive examinations personally performed and interpreted by the practitioner to maintain an adequate level of competence in perioperative TEE.5,14–18 Additional components of ongoing training include, but are not limited to, attendance at conferences and workshops to stay abreast of the latest techniques and advances, case conferences, and case reviews. Provision of such opportunities is considered a responsibility of the training program. The Canadian guidelines, however, recommend that the director level of expertise requires performance of 75 comprehensive TEE examinations annually.17,18

1 de Bruijn N.P., Clements F.M., Kisslo J.A. Intraoperative transesophageal color flow mapping: Initial experience. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:386-390.

2 Eltzschig H.K., Rosenberger P., Loffler M., et al. Impact of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography on surgical decisions in 12,566 patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:845-852.

3 Minhaj M., Patel K., Muzic D., et al. The effect of routine intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography on surgical management. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;21:800-804.

4 Schulmeyer M.C., Santelices E., Vega R., et al. Impact of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography during noncardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006;20:768-771.

5 Aronson S., Thys D.M. Training and certification in perioperative transesophageal echocardiography: A historical perspective. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1422-1427.

6 Morewood G.H., Gallagher M.E., Gaughan J.P., et al. Current practice patterns for adult perioperative transesophageal echocardiography in the United States. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:1507-1512.

7 Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:986-1006.

8 Cahalan M.K., Abel M., Goldman M., et al. American Society of Echocardiography and Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists task force guidelines for training in perioperative echocardiography. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1384-1388.

9 Cahalan M.K., Foster E. Training in transesophageal echocardiography: In the lab or on the job? Anesth Analg. 1995;81:217-218.

10 Savage R.M., Licina M.G., Koch C.G., et al. Educational program for intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:399-403.

11 Pearlman A.S., Gardin J.M., Martin R.P., et al. Guidelines for optimal physician training in echocardiography. Recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography Committee for Physician Training in Echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:158-163.

12 Pearlman A.S., Gardin J.M., Martin R.P., et al. Guidelines for physician training in transesophageal echocardiography: Recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography Committee for Physician Training in Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1992;5:187-194.

13 Stewart W.J., Aurigemma G.P., Bierman F.Z., et al. Guidelines for training in adult cardiovascular medicine. Core Cardiology Training Symposium (COCATS). Task Force 4: Training in echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:16-19.

14 Quinones M.A., Douglas P.S., Foster E., et al. ACC/AHA clinical competence statement on echocardiography: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine Task Force on Clinical Competence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:687-708.

15 Quinones M.A., Douglas P.S., Foster E., et al. ACC/AHA clinical competence statement on echocardiography: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine Task Force on clinical competence. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16:379-402.

16 Quinones M.A., Douglas P.S., Foster E., et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association clinical competence statement on echocardiography: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians—American Society of Internal Medicine Task Force on Clinical Competence. Circulation. 2003;107:1068-1089.

17 Beique F., Ali M., Hynes M., et al. Canadian guidelines for training in adult perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. Recommendations of the Cardiovascular Section of the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:1015-1027.

18 Beique F., Ali M., Hynes M., et al. Canadian guidelines for training in adult perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. Recommendations of the Cardiovascular Section of the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53:1044-1060.

19 Mahmood F., Christie A., Matyal R. Transesophageal echocardiography and noncardiac surgery. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;12:265-289.

20 Bose R., Matyal R., Panzica P., et al. Transesophageal echocardiography simulator: A new learning tool. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009;23:544-548.

21 Weyman A.E., Butler A., Subhiyah R., et al. Concept, development, administration, and analysis of a certifying examination in echocardiography for physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2001;14:158-168.

22 Aronson S., Butler A., Subhiyah R., et al. Development and analysis of a new certifying examination in perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:1476-1482.

23 Konstadt S.N., Reich D.L., Rafferty T. Validation of a test of competence in transesophageal echocardiography. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1996;10:311-313.

24 Oxorn D. Certification in perioperative TEE. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1844.