Chapter 52 Transcochlear Approach to Cerebellopontine Angle Lesions

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

The transcochlear approach evolved from the inability to excise the base of implantation and control the blood supply of these near-midline and midline tumors with other surgical approaches. Total removal of these lesions through a suboccipital approach is often impossible because of the interposition of the cerebellum and the brainstem.1,2 The transpalatal-transclival approach was attempted for these intradural midline lesions, with little success, during the early 1970s.3 The exposure was often inadequate; the field is relatively far from the surgeon; the blood supply is lateral, away from the surgeon’s view; and the risk of intracranial complications caused by oral contamination is increased. The retrolabyrinthine approach is limited in its forward extension by the posterior semicircular canal. Tumor access with the translabyrinthine approach is limited anteriorly by the facial nerve, which impedes removal of the tumor’s base of implantation, which is anterior to the IAC, around the intrapetrous carotid artery, or anterior to the brainstem. The development of the extended middle fossa approach and combined transpetrous approach enables complete removal of petroclinoid meningiomas, and is used in patients with useful hearing.4–6 The primary limitation with this approach is poor access to tumors with inferior or midline extensions.7,8 The endoscopic-assisted transsphenoidal approach has been gaining acceptance as an alternative approach to access midline intracranial lesions arising from the clivus and petrous apex lesions (Stamm A, personal communication, 2008).

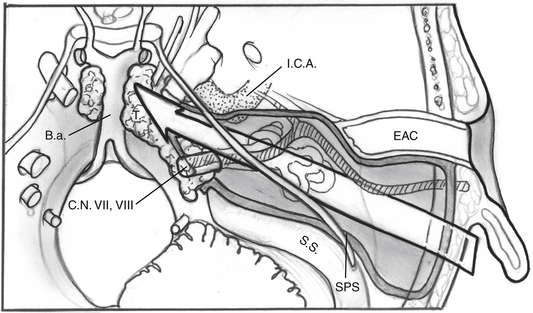

The transcochlear approach was developed by House and Hitselberger2,3 in the early 1970s as an anterior extension of the translabyrinthine approach. It involves rerouting of the facial nerve posteriorly and the removal of the cochlea and petrous apex, which exposes the area of the intrapetrous internal carotid artery. This approach affords wide intradural exposure of the anterior CPA; CN V, VII, VIII, IX, X, and XI; both sixth cranial nerves; the clivus; and the basilar and vertebral arteries, without using any brain retractors. The contralateral cranial nerves and the opposite CPA are also visible.9 This wide exposure affords removal of the tumor base and its arterial blood supply from the internal carotid artery, which is particularly important in the treatment of meningiomas.2 Adding excision and closure of the external auditory canal (EAC), as advocated by Brackmann (personal communication, 1987), increases further the anterior exposure for lesions of the petroclival regions and prepontine cistern. Smaller lesions can be reached without rerouting the facial nerve (transotic approach).

ADVANTAGES OF TRANSCOCHLEAR APPROACH

This approach requires no cerebellar or temporal lobe retraction. Exposure and dissection of the petrous apex and clivus allows excellent exposure of the midline and complete removal of the tumor, its base of implantation, and its blood supply. This is of particular importance in meningiomas.10,11

PATIENT EVALUATION AND PREOPERATIVE COUNSELING

Individuals with tumors that require transcochlear surgery may have minimal symptoms, with tumors that can be quite large at the time of diagnosis.1,12 Petrous apex epidermoids manifest with unilateral hearing loss and tinnitus in 80% of the cases. Facial twitch is also common. Imbalance, ataxia, and parietal or vertex headaches may be the only complaints in 20% of patients.13 Patients with meningiomas and intradural epidermoids may be nearly symptom-free until they present with CN V findings and signs of increased intracranial pressure.14,15 There is a high rate of jugular foramen syndrome in patients with meningiomas.1 Seizures, dysarthria, and late signs of dementia from hydrocephalus were common presenting symptoms in the past.13 Hearing and vestibular functions are frequently normal, and acoustic reflex decay or abnormal auditory brainstem response audiometric results may be the only anomalies.1

Imaging using high-resolution computed tomography (CT) with contrast enhancement, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is essential for diagnosis and surgical planning.16 Petrous apex and intradural epidermoids are expansile, spherical, or oval lesions, with scalloped bone edges on CT. They are isodense to cerebrospinal fluid on CT, with capsular enhancement. On MRI, they are hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Meningiomas enhance with contrast on MRI, and manifest with a “dural tail.” Evaluation of blood supply of some tumors may also require MRA. In tumors surrounding or invading the intrapetrous carotid artery, patency of the circle of Willis is accessed, and carotid residual pressure is measured; preoperative balloon occlusion of the carotid artery and selective embolization are performed 1 day before surgery. Radioisotope, xenon, or positron emission tomography studies are used to assess cerebral perfusion during occlusion studies.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

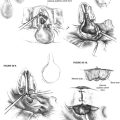

A wide mastoidectomy and labyrinthectomy are performed, exposing the IAC. When first described by House and Hitselberger in 1976,3 the tympanic ring was not removed, and only the facial recess was opened to permit anterior exposure. Brackmann, after Fisch, modified the approach by removing the entire tympanic ring, malleus, incus and stapes, and blind-sac closing the EAC.17,18

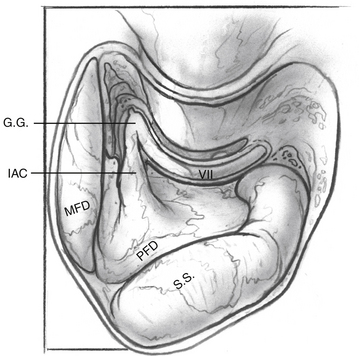

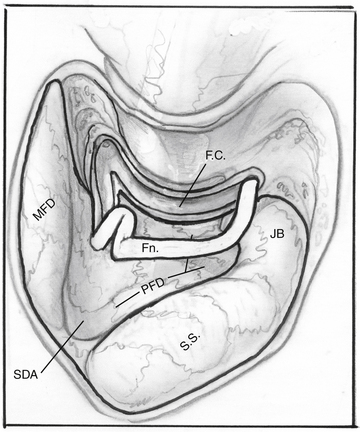

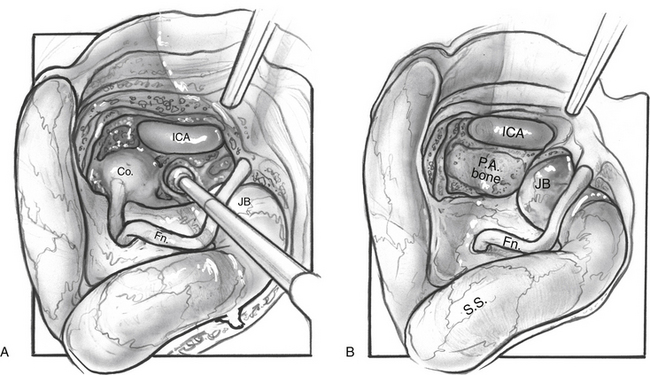

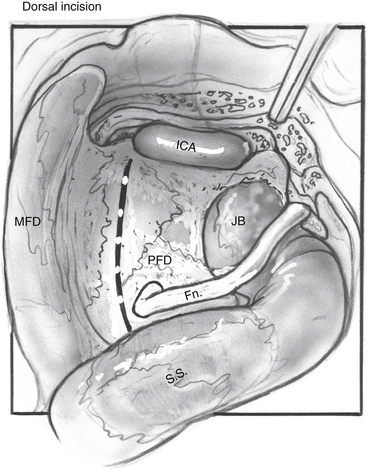

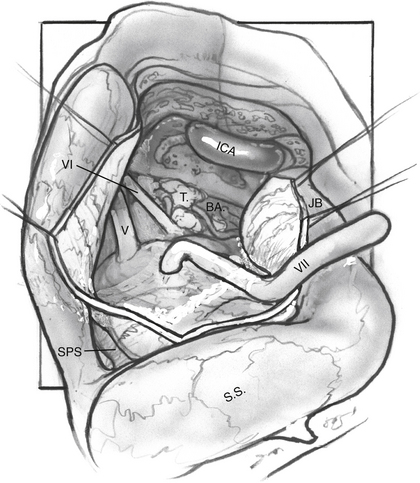

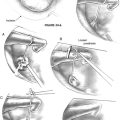

The facial nerve is completely skeletonized, with transection of the greater superficial petrosal and chorda tympani nerves, and is rerouted posteriorly out of the fallopian canal. The cochlea and the fallopian canal are completely drilled out, and the internal carotid artery is skeletonized. A large triangular window is created into the skull base. Its superior boundary is the superior petrosal sinus; inferiorly, it extends below and medial to the inferior petrosal sinus into the clivus. Anteriorly lies the region of the intrapetrous internal carotid artery, and the apex of the triangle is just beneath Meckel’s cave. When the dura is opened, this window gives excellent direct access to the midline without need of any retraction (Fig. 52-1). After tumor removal, the dura is reapproximated with dural silk, the eustachian tube is packed with absorbable knitted fabric (Surgicel) and muscle, and abdominal fat is used to fill the dura and mastoidectomy defects and to cushion the facial nerve.

Mastoidectomy

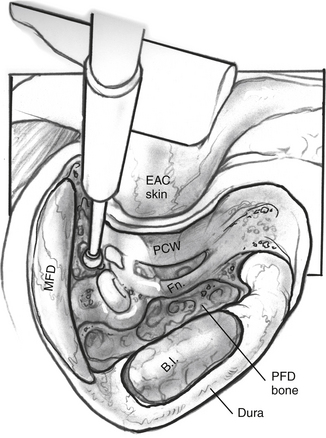

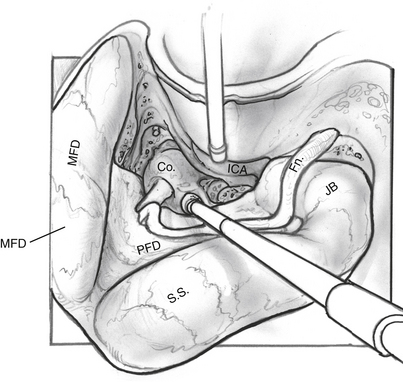

An extended mastoidectomy (Fig. 52-2) is carried out with microsurgical cutting and diamond burrs and continuous suction-irrigation. Bone removal is started along two lines: one along the linea temporalis and another tangential to the EAC. The mastoid antrum is opened, and the lateral semicircular canal is identified. The lateral semicircular canal is the most reliable landmark in the temporal bone, and allows the dissection to proceed toward delineating the vertical fallopian canal and the osseous labyrinth.

Labyrinthectomy and Skeletonization of Internal Auditory Canal

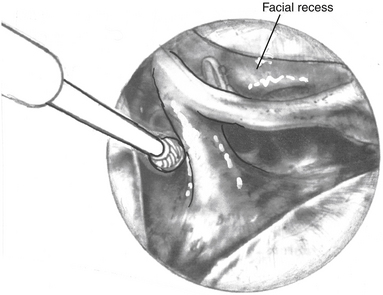

Dissection of the perilabyrinthine cells down to the lateral semicircular canal is completed (Fig. 52-3). The facial nerve is identified in its vertical portion between the nonampullated end of the lateral semicircular canal and the stylomastoid foramen. At this stage, exposing the perineurium of the nerve is unnecessary, but it should be clearly and unmistakably identified in its vertical course.

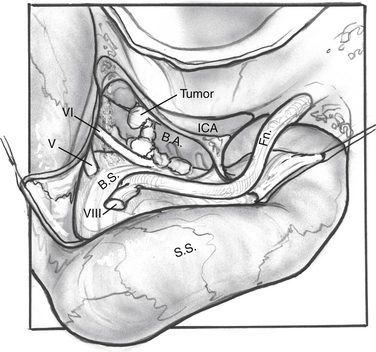

Tumor Removal (Fig. 52-7)

The nerve is protected and kept moist.

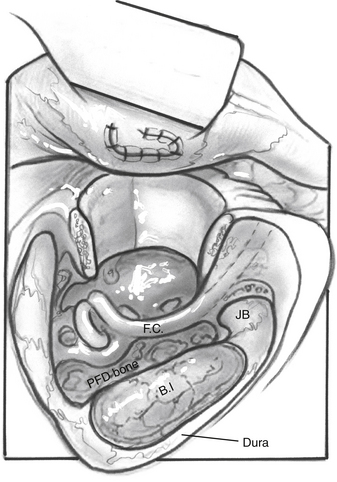

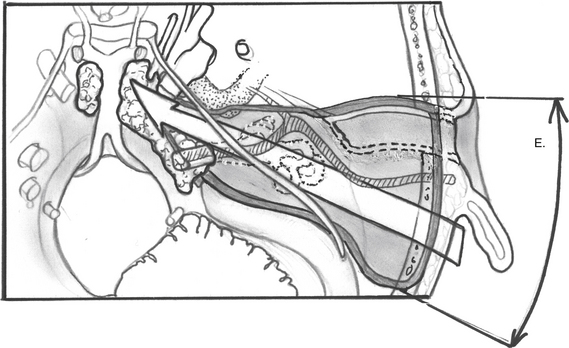

For dumbbell-shaped tumors, the tentorium can be opened to excise the part of the tumor that is lying in the middle fossa. Care is taken not to injure the vein of Labbé posteriorly or CN IV at the edge of the tentorium. Figures 52-8 to 52-12 illustrate the transcochlear approach with removal of the tympanic bone and blind closure of the EAC, which is done when further anterior exposure is necessary.

FIGURE 52-8 Increased anterior exposure obtained with removal of bony external auditory canal. E, exposure.

RESULTS

In 1982, De la Cruz1 reviewed the results of 16 patients in whom the transcochlear approach was used. A combination transcochlear/middle fossa approach was used in the three cases involving dumbbell-shaped tumors in the posterior and middle cranial fossae. Total tumor removal was possible in 13 of the 16 patients. Each of the other three patients had had surgery elsewhere and presented with large recurrent meningiomas and extensive neurologic deficits preoperatively. During the transcochlear approach, scraps of tumor were left behind on the vertebral artery in two of these cases. None of these patients had tumor recurrence. Four patients had facial paresis or twitch preoperatively; of the other 12, 4 had permanent facial paralysis because of tumor involvement of the nerve, and 7 had temporary paresis with good recovery of facial function. This paresis was attributed primarily to removal of blood supply to the nerve, and these patients were operated on before facial nerve monitoring was available. Two deaths occurred in this series. One patient had bleeding from the vertebral artery 1 week postoperatively, requiring clipping of the vessel, with subsequent infarction of the brainstem; the other patient was diabetic and died 1 month postoperatively because of gram-negative shock from pyelonephritis. He was one of the patients reported as having a “permanent” facial paralysis. Autopsy revealed no evidence of residual tumor on the facial nerve or elsewhere.

In 1989, Yamakawa and colleagues15 published their results with the suboccipital approach, reporting subtotal tumor removal in 17 of 29 patients with intracranial epidermoids and tumor recurrence in 7 patients. One of 14 patients with CPA tumors had postoperative CN VII paralysis, 6 had CN VI palsy, 4 had dysphagia, and 2 had hearing loss. The report by Yasargil and associates19 published in the same year analyzed results in 43 patients; 35 had epidermoid tumors, whereas others had intracranial dermoid tumors. There were no recurrences. Aseptic meningitis and transient cranial nerve palsies were the most common complications.

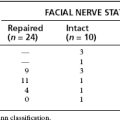

In 2001, Angeli and coworkers20 reviewed 24 cases operated on between 1985-1995 at the House Ear Clinic using the transcochlear approach or 1 of its modifications. In 1 case, a modified transotic approach was used (small melanoma); in 2 other cases, the transcochlear approach was extended inferiorly with an infratemporal and upper neck dissection (1 glomus and 1 meningioma). Most of the tumors (16 of 24) were meningiomas. The other tumors included 4 cholesteatomas, 2 melanomas, 1 glomus, and 1 ependymoma. The EAC was closed in 12 patients. Complete removal was achieved in 82% of tumors (average follow-up time 36 months). In 2 cases (8%), it was elected intraoperatively to do a subtotal tumor resection owing to excessive blood loss (intracranial glomus jugulare tumor) in 1 and unresectability (melanoma invading the brainstem) in 1. Most patients had some degree of facial nerve dysfunction immediately after surgery, and 12 of 20 patients subsequently improved to House-Brackmann grade III or better. A significant incidence of temporary facial weakness was expected as a result of posterior facial nerve transposition. 59% of patients had permanent neurologic sequelae because of either the surgery or their disease. The most common neurologic deficit was diplopia (27%). Other complications included dysphagia, facial numbness, unsteadiness, hoarseness, hemiparesis, and dysarthria.

In 2004, Gonzalez and associates21 reported 32 patients with 34 anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysms. Surgical approaches included retrosigmoid, transcochlear, translabyrinthine, and orbitozygomatic. The transcochlear approach was used in 4 patients; 1 patient had small bilateral aneurysms that were approached, with good results, from the same side by taking advantage of the wide corridor obtained with a transcochlear approach. Complications reported were involvement of CN VI, VII, and VIII, and CSF leak.

Siwanuwatn and coworkers22 quantitatively assessed the working areas and angles of attack associated with retrosigmoid, combined petrosal, and transcochlear craniotomies, using silicone-injected cadaveric heads. They reported that the transcochlear approach provided significantly greater working areas at the petroclivus and brainstem than the combined petrosal and retrosigmoid approaches (P < .001). The horizontal and vertical angles of attack achieved using the transcochlear approach were wider than the angles of the combined petrosal and retrosigmoid at the Dorello canal and the origin of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (P < .001). They concluded that the transcochlear approach provides the widest corridor, improving the working area and angle of attack to both areas.

In 2006, Leonetti and colleagues24 reported 29 patients with large meningiomas of the CPA surgically treated through a combined retrosigmoid/transpetrosal/transcochlear approach. Total tumor removal was achieved in 19 of 29 (67%) of the patients, and the facial nerve was anatomically preserved in 26 of 29 (89%) of the cases. Cerebrospinal fluid leakage was seen in 3.5% of the patients, and additional transient cranial nerve deficits were noted in 14% of the cases, but no significant neurologic sequelae occurred. Of the 10 patients with residual tumor, 6 have been stable without growth, 2 were treated with reoperation for regrowth of disease, and 2 were controlled with localized radiotherapy. These investigators concluded that this combined lateral transtemporal approach provided wide exposure to the CPA and optimized the surgical extirpation of the 29 meningiomas presented in their series.

COMPLICATIONS AND THEIR MANAGEMENT

Meningitis may occur after complete excision of intracranial epidermoids, and the incidence increases when the tumor capsule is left in place.19,24

Postoperative pain is not as severe as that seen with the suboccipital approach and is managed adequately with analgesics. With this approach, tumor recurrence is rare when all visible tumor has been removed. Patients with recurrences do not present typically and may have vague complaints of unsteadiness or trigeminal symptoms several years after the initial resection.1 Annual follow-up with gadolinium-enhanced and fat-suppression MRI is necessary. In cases of suspected tumor regrowth or recurrence, complete re-evaluation is performed, and removal of the recurrent tumor is advised. Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery and stereotactic radiotherapy are also treatment options for residual or recurrent meningiomas.26

1. De la Cruz A. The transcochlear approach to meningiomas and cholesteatomas of the cerebellopontine angle. In: Brackmann D.E., editor. Neurological Surgery of the Ear and Skull Base. New York: Raven Press; 1982:353-360.

2. House W.F., De la Cruz A. Transcochlear approach to the petrous apex and clivus. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1977;84:927-931.

3. House W.F., Hitselberger W.E. The transcochlear approach to the skull base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1976;102:334-342.

4. Hitselberger W.E., Horn K.L., Hankinson H., et al. The middle fossa transpetrous approach for petroclival meningiomas. Skull Base Surg. 1993;3:130-135.

5. Spetzler R.F., Daspit C.P., Pappas C.T. The combined supratentorial and infratentorial approach for lesions of the petrous and clival regions: Experience with 46 cases. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:588-599.

6. Daspit C.P., Spetzler R.F., Pappas C.T. Combined approach for lesions involving the cerebellopontine angle and skull base: Experience with 20 cases-preliminary report. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105:788-796.

7. Shiobara R., Ohira T., Kanzaki J., Toya S. A modified extended middle cranial fossa approach for acoustic nerve tumors: Results of 125 operations. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:358-365.

8. Wigand M.E., Haid T., Berg M. The enlarged middle cranial fossa approach for surgery of the temporal bone and the cerebellopontine angle. Arch Otol Rhinol Otolaryngol. 1989;246:299.

9. Jackler R.K., Sim D.W., Gutin P.H., Pitts L.H. Systematic approach to intradural tumors ventral to the brain stem. Am J Otol. 1995;16:39-51.

10. Arriaga M., Shelton C., Nassif P., Brackmann D.E. Selection of surgical approaches for meningiomas affecting the temporal bone. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:738-744.

11. Thedinger B.A., Glasscock M.E.III, Cueva R.A. Transcochlear transtentorial approach for removal of large cerebellopontine angle meningiomas. Am J Otol. 1992;13:408-415.

12. Brackmann D.E., Anderson R.G. Cholesteatomas of the cerebellopontine angle. In: Silverstein H., Norrell H., editors. Neurological Surgery of the Ear. Birmingham: Aesculapius; 1979:340-344.

13. De la Cruz A., Doyle K.J. Epidermoids of the cerebellopontine angle. In: Jackler R.A., Brackmann D.E., editors. Neurotology. York, PA: Spectrum; 1994:823-834.

14. Nager G.T. Epidermoids involving the temporal bone: Clinical, radiological, and pathological aspects. Laryngoscope. 1975;2(Suppl):1-22.

15. Yamakawa K., Shitara N., Genka S., et al. Clinical course and surgical prognosis of 33 cases of intracranial epidermoid tumors. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:568-573.

16. Mafee M.F. MRI and CT in the evaluation of acquired and congenital cholesteatomas of the temporal bone. J Otolaryngol. 1993;22:239-248.

17. Brackmann D.E. Translabyrinthine Transcochlear approaches. In: Sekhas L.N., Janecka I.P., editors. Surgery of Cranial Base Tumors. New York: Raven Press; 1993:351-365.

18. Friedman R.A., Brackmann D.E. Transcochlear Approach Operative Techniques in. Neurosurgery. 1999;Vol 2, No 1:39-45.

19. Yasargil M.G., Abernathy C.D., Sarioglu A.C. Microneurosurgical treatment of intracranial dermoid and epidermoid tumors. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:561-567.

20. Angeli S.I., De la Cruz A., Hitselberger W.E. The transcochlear approach revisited. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:690-695.

21. Gonzalez L.F., Alexander M.J., McDougall C.G., Spetzler R.F. Anteroinferior cerebellar artery aneurysms: Surgical approaches and outcomes—a review of 34 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:1025-1035.

22. Siwanuwatn R., Deshmukh P., Figueiredo E.G., et al. Quantitative analysis of the working area and angle of attack for the retrosigmoid, combined petrosal, and transcochlear approaches to the petroclival region. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:137-142.

23. Leonetti J.P., Anderson D.E., Marzo S.J., et al. Combined transtemporal access for large (>3 cm) meningiomas of the cerebellopontine angle. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:949-952.

24. Cantu R.C., Ojemann R.G. Lucosteroid treatment of keratin meningitis following removal of a fourth ventricle epidermoid tumor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1968;31:75.

25. Guidetti B., Gagliardi F.M. Epidermoid and dermoid cysts. J Neurosurg. 1977;47:12-18.

26. Mattozo C.A., De Salles A.A., Klement I.A., et al. Stereotactic radiation treatment for recurrent nonbenign meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:846-854.