Chapter 40 Transcanal Labyrinthectomy

Labyrinthectomy is an effective surgical procedure for the management of unremitting or poorly compensated unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction in the presence of ipsilateral, profound, or severe sensorineural hearing loss. The physiologic rationale is that central vestibular compensation is more rapid and complete for unilateral absence of peripheral vestibular function than for unilateral abnormal function, either episodic or chronic.1

Unilateral vestibular ablation has been advocated for more than 6 decades. Selective or total eighth cranial nerve transection by the suboccipital approach was introduced by Dandy in 1928.2 Destruction of the peripheral end organs of the vestibular labyrinth was introduced by Jansen3 in 1895 for complications of suppurative labyrinthitis. This technique was applied to unilateral peripheral vestibular disturbance by Milligan4 and by Lake5 in 1904, and was reintroduced by Cawthorne6 in 1943 as a canal wall up technique. In his original description, Cawthorne apparently ablated only the lateral semicircular canal. In its current form, complete vestibular ablation is accomplished by exenteration of all three of the semicircular canals and both maculae.

The earliest report of a transcanal procedure for vertigo is credited to Crockett,7 who in 1903 described removal of the stapes as an effective treatment for vertigo. Lempert8 described an endaural transmeatal approach to the oval and round windows for Meniere’s disease. In this procedure, the stapes was removed, and the round window was punctured to “decompress” the membranous labyrinth. There was no mention, however, of the importance of destruction of the vestibular end organs. The modern transcanal labyrinthectomy for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction was introduced by Schuknecht in 19569 and by Cawthorne in 1957.10 In a series of articles, Schuknecht’s technique evolved to emphasize the importance of destruction of all five vestibular end organs.11–13 Armstrong14 and Ariagno15 also emphasized the importance of total ablation of peripheral vestibular function.

PATIENT SELECTION

Although the published indications for labyrinthectomy have included hearing levels poorer than a 50 dB speech reception threshold and a 50% discrimination score, in view of the incidence of bilateral Meniere’s disease of 10% to 40%, as reported by Greven and Oosterveld16 and Paparella and Griebie,17 labyrinthectomy should be reserved for cases in which the hearing loss is severe to profound, generally with a speech reception threshold of 75 dB or worse and a speech discrimination score of less than or equal to 20%. This threshold for labyrinthectomy should be increased if hearing in the contralateral ear is not in the normal or near-normal range.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

A complete history and otolaryngologic–head and neck examination should be performed. Bilateral behavioral audiometry, including pure tone thresholds for air and bone conduction and speech discrimination, is necessary. Vestibular testing should include at least bilateral caloric function, best done by electronystagmography. This assessment is necessary to evaluate the possibility of bilateral vestibular dysfunction, and to confirm vestibular dysfunction in the affected ear based on audiometry and history. Hallpike’s positional testing and evaluation for the presence of the fistula and Hennebert’s signs should be done.18 A neurologic examination should be done to rule out concurrent cranial nerve, cerebellar, or other neurologic dysfunction that would belie the working diagnosis of a peripheral unilateral vestibular dysfunction.

PREOPERATIVE PATIENT COUNSELING AND INFORMED CONSENT

Preoperative counseling should include a discussion of the natural history of Meniere’s disease, including the spontaneous rate of remission of approximately 70% within 8 years and the 10% to 40% incidence of involvement of the second ear.19 In addition, the patient should be aware that all hearing will be lost in the ear receiving surgery, and that the effect on tinnitus is unpredictable. The patient must be aware that immediately postoperatively there is a period of vertigo similar to a typical attack, and that this episode lasts several days. In addition, a period of protracted dysequilibrium may occur, and in patients with negative indicators for compensation, there may be some degree of permanent disability that requires a rehabilitative program.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Incision and Exposure

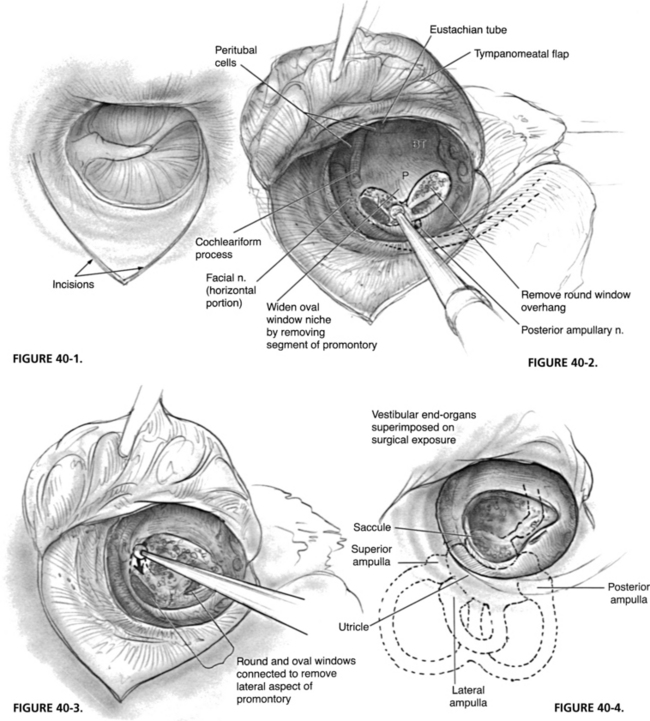

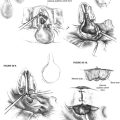

The procedure is done by the transcanal approach in most cases. Occasionally, with a very narrow meatus, an endaural incision or postauricular transcanal approach may be useful. An anteriorly based tympanomeatal flap, longer than that used for stapedectomy, is elevated to allow wide curettage in the oval and round window areas (Fig. 40-1). The horizontal segment of the facial nerve, the entire stapes footplate, and the entire round window niche all should be easily visible after elevation of the flap and curettage of the posterior aspect of the bony tympanic annulus.

Preparation for Opening the Vestibule

The incus is removed. The stapedial tendon is sectioned, and the stapes is removed in a rocking motion in an anteroposterior direction to allow removal of the stapes without fracture. Every effort should be made to avoid aspiration of the vestibule at this time to avoid displacement of the utricle. To obtain access to the vestibular end organs, the oval window may simply be enlarged at its anterior and inferior aspects (Fig. 40-2), or the oval and round windows may be connected to remove a segment of the promontory (Fig. 40-3). At this juncture, an attempt may be made to expose the posterior ampullary nerve. It may be exposed near the posterior aspect of the round window niche (see Figs. 40-2 and 40-3), which affords the surgeon an opportunity to practice identification and section of the posterior ampullary nerve, and helps guarantee a more complete labyrinthectomy. In a study of labyrinthectomy in the cat, Schuknecht23 reported that subtotal destruction of the vestibular end organs occurred in 10 of 24 ears, and that the crista of the posterior semicircular canal was the end organ most commonly missed.

Removal of Vestibular End Organs

Total mechanical destruction of the five vestibular end organs is the goal of this surgery. The normal position of the vestibular end organs and their relationship to the oval and round windows are shown in Figure 40-4. Endolymphatic hydrops or intraoperative loss of perilymph may cause displacement of these end organs, however. During aspiration or loss of perilymphatic fluid, the utricle usually retracts superiorly to lie medial to the horizontal segment of the facial nerve. Before aspiration of the vestibule, the utricle should be removed with a 4 mm hook, whirlybird, or utricular hook in the superior aspect of the vestibule (Fig. 40-5).

The utricle is substantial and can easily be seen under low power of the operating microscope. Avulsion of the utricle from the vestibule usually results in avulsion of the cristae of lateral and superior semicircular canals as well, but not that of the posterior semicircular canal. The saccule is destroyed mechanically by aspiration of the medial aspect of the vestibule in the area of the spherical recess. Manipulation of the medial aspect of the vestibule must be done with care to avoid fracture of the cribrose area, which would result in profuse leakage of cerebrospinal fluid from the internal auditory canal. Any residual neuroepithelium of the cristae of the three semicircular canals is destroyed by mechanical probing. The surgeon can feel the 4 mm hook drop into the ampullary ends of the bony canals (Fig. 40-6). This entire technique should be practiced in the temporal bone laboratory to gain familiarity with the anatomy and proficiency in this procedure.

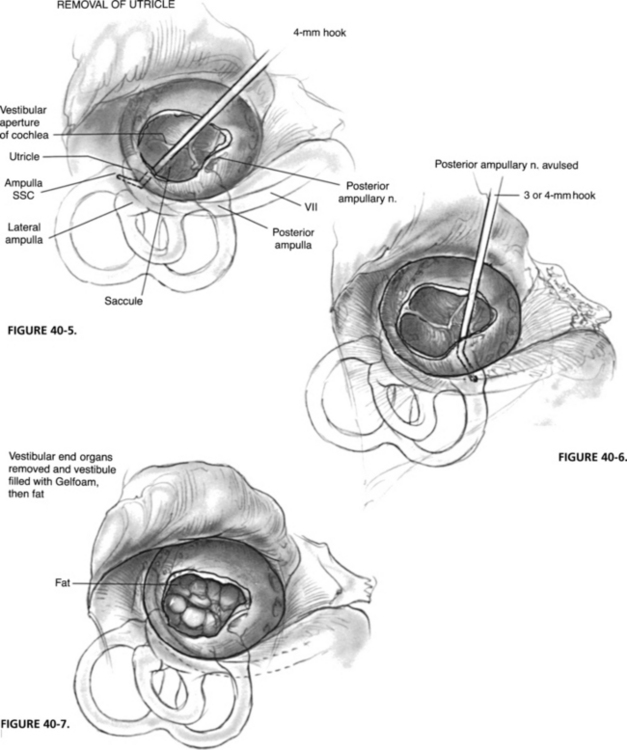

After destruction of the vestibular end organs, the vestibule is usually packed with absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) or, preferably, a small fat graft from the ear lobe (Fig. 40-7). Some surgeons recommend the use of gentamicin or streptomycin-soaked Gelfoam in the medial aspect of the vestibule to guarantee destruction of residual neuroepithelium. As seen in Figure 40-8, the absence of a tissue graft of the open oval window results in a pneumolabyrinth postoperatively. Generally, this result does not cause a problem, but a tissue seal with fat or fascia provides a better barrier between the middle ear and cerebrospinal fluid spaces. Leakage of cerebrospinal fluid after aspiration of the vestibule should be repaired with a tissue seal. The tympanomeatal flap is returned to the posterior canal wall and held in place with packing, and the procedure is terminated.

SURGICAL COMPLICATIONS AND MANAGEMENT

Intraoperative Complications

Failure to Find the Utricle

Identification and removal of the utricle are essential to a complete labyrinthectomy. When perilymph has been aspirated from the vestibule, the utricle may retract superiorly under the horizontal segment of the facial nerve. The use of a modified right angled hook (utricular hook) (see Fig. 40-5) or a right angled No. 3 Fr suction may aid in retrieval. Alternatively, the utricle remains fixed to the lateral and superior semicircular canals, which may be palpated in the depths of the vestibule. A wide exposure achieved by removing the bone from the inferior aspects of the oval window or by connecting the round and oval windows improves access to the vestibule and its contents.

HISTOPATHOLOGY OF LABYRINTHECTOMY

Postmortem histopathology of temporal bones from patients who, in life, underwent labyrinthectomy has been reported by Belal and Ylikoski,20 Linthicum and associates,21 Pulec,22 and Schuknecht,23 and all have reported examples of incomplete mechanical disruption of the vestibular end organ after transcanal labyrinthectomy. These results underscore the importance of proper exposure, removal of the utricle, and thorough probing of the ampullae. In an animal study of labyrinthectomy, Schuknecht23 reported that the neuroepithelium of the posterior semicircular canal persisted in 10 of 24 ears. This fact argues for wider exposure of the vestibule by connecting the oval and round windows, and for selective destruction of the posterior ampullary nerve, as recommended by Gacek,24 as an additional step to guarantee complete labyrinthectomy.

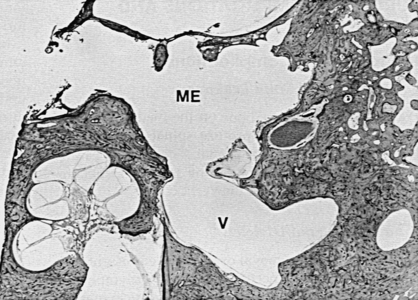

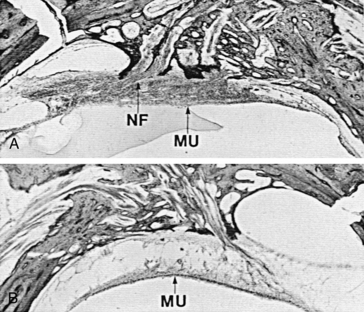

Linthicum and associates21 and Belal and Ylikoski20 reported traumatic neuroma within the vestibule after labyrinthectomy (Fig. 40-9). Both groups interpret this finding as an indication of the superiority of the translabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. In one case, a traumatic neuroma was also described after transmastoid labyrinthectomy and section of the superior vestibular nerve. In an experimental study in the cat, Schuknecht23 reported no evidence of regeneration of vestibular nerve fibers or formation of traumatic neuroma after labyrinthectomy. In temporal bone specimens from human subjects who had undergone transcanal labyrinthectomy during life, degeneration of the vestibular nerve was seen in one, and a proliferation of nerve fibers was identified in another (Fig. 40-10). No evidence exists, however, to suggest that nerve fibers, whether residual or regenerative, can contribute to afferent vestibular input if the vestibular neuroepithelium distal to it has been destroyed.

Two patients are cited by Linthicum and associates21 as examples of failure of labyrinthectomy because of traumatic neuroma. In the first case, reported by Hilding and House,25 the neuroma was uncovered at revision labyrinthectomy, but there was no evidence that the persistent symptoms resulted from the neuroma, rather than from residual neuroepithelium.

In the second case, reported by Pulec,22 a traumatic neuroma was identified by postmortem temporal bone histopathology in a patient with persistent vestibular symptoms for 10 years after labyrinthotomy, not labyrinthectomy. In addition, despite no response on the premortem caloric testing, the ampulla of the posterior semicircular canal was normal. In this case, the persistent vestibular symptoms probably resulted from residual vestibular neuroepithelium rather than from the traumatic neuroma.

RESULTS OF SURGERY

The reported results as measured by ablation of caloric function or cure of the patient have varied considerably. Linthicum and associates21 reported that only 17 (60%) of 25 patients who underwent labyrinthectomy were cured or improved by this approach; they advocated translabyrinthine nerve section as a more reliable method of ablating vestibular function. Ariagno15 found, however, a 98% success rate in controlling peripheral vestibular disorders through transcanal labyrinthectomy, emphasizing the need for total destruction of the vestibular end organs by joining the oval and round windows. Hammerschlag and Schuknecht26 reported a cure of episodic vertigo in 120 (96.8%) of 124 patients by transcanal labyrinthectomy. The remaining four patients had continuing dysequilibrium, and three with persistent vestibular response by postoperative ice water caloric tests were cured by revision transcanal labyrinthectomy, resulting in an overall cure rate of 99%.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

The advent of cochlear implantation as a possibility for rehabilitation of profoundly deaf patients, and the fact that 10% to 40% of patients with Meniere’s disease have bilateral involvement require consideration of the implications for eventual implantation after any surgical procedure for management of vestibular disturbance. Chen and colleagues27 reported on three temporal bone cases from patients who in life had undergone labyrinthectomy, two by the transcanal route and one by the transmastoid approach. Based on the patency of the cochlear duct, remaining spiral ganglion, and neural elements, and maintenance of the organ of Corti as evaluated by histopathologic study, these authors predicted that labyrinthectomy would not preclude subsequent cochlear implantation. In six patients who had undergone previous unilateral transmastoid labyrinthectomy, Lambert and coworkers28 reported that round window electric stimulation resulted in a psychophysical response to stimulus in all patients and electrically evoked middle latency response in five of six patients. Kveton and associates29 reported an ear deafened by transmastoid labyrinthectomy with subsequent successful cochlear implantation resulting in speech comprehension comparable to that of patients deafened by other causes.

1. Stockwell C.W., Graham M.D. Vestibular compensation following labyrinthectomy and vestibular neurectomy. In: Nadol J.B.Jr., editor. Second International Symposium for Ménière’s Disease. Amsterdam: Kugler & Ghedini Publishers; 1989:489-498.

2. Dandy W.E. Ménière’s disease: Its diagnosis and a method of treatment. Arch Surg. 1928;16:1127-1152.

3. Jansen A. Referat uber die operationsmethoden bei den verschiedenen otitischen gehirukoneplikationen. Verh Dtsch Otol Gesell (Jena); 1895. p 96

4. Milligan W. Ménière’s disease: A clinical and experimental inquiry. BMJ. 1904;2:1228.

5. Lake R. Removal of the semicircular canals in a case of unilateral aural vertigo. Lancet. 1904;1:1567-1568.

6. Cawthorne T.E. The treatment of Ménière’s disease. J Laryngol Otol. 1943;58:63-71.

7. Crockett E.A. The removal of the stapes for the relief of auditory vertigo. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1903;12:67-72.

8. Lempert J. Lempert decompression operation for hydrops of the endolymphatic labyrinth in Ménière’s disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1948;47:551-570.

9. Schuknecht H.F. Ablation therapy for the relief of Ménière’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1956;66:859-870.

10. Cawthorne T. Membranous labyrinthectomy via the oval window for Ménière’s disease. J Laryngol Otol. 1957;71:524-527.

11. Schuknecht H.F. Ablation therapy in the management of Ménière’s disease. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl (Stockh). 1957;132:1-42.

12. Schuknecht H.F. Destructive therapy for Ménière’s disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1960;71:562-572.

13. Schuknecht H.F. Destructive labyrinthine surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1973;97:150-151.

14. Armstrong B.W. Transtympanic vestibulotomy for Ménière’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1959;69:1071-1074.

15. Ariagno R.P. Transtympanic labyrinthectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1964;80:282-286.

16. Greven A.J., Oosterveld W.J. The contralateral ear in Ménière’s disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1978;101:608-612.

17. Paparella M.M., Griebie M.S. Bilaterality of Ménière’s disease. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh). 1984;97:233-237.

18. Nadol J.B.Jr. Positive “fistula sign” with an intact tympanic membrane. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1974;100:273-278.

19. Silverstein H., Smouha E., Jones R. Natural history versus surgery for Ménière’s disease. In: Nadol J.B.Jr., editor. Second International Symposium for Ménière’s Disease. Amsterdam: Kugler & Ghedini Publishers; 1989:543-544.

20. Belal A., Ylikoski J. Pathology as it relates to ear surgery, II: Labyrinthectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1983;97:1-10.

21. Linthicum F.H., Alonso A., Denia A. Traumatic neuroma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1979;105:654-655.

22. Pulec J.L. Labyrinthectomy: Indications, technique, and results. Laryngoscope. 1974;84:1552-1573.

23. Schuknecht H.F. Behavior of the vestibular nerve following labyrinthectomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1982;91(5 Suppl 97):16-32.

24. Gacek R.R. Transection of the posterior ampullary nerve for the relief of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1974;83:596-605.

25. Hilding D.A., House W.F. Acoustic neuroma”: Comparison of traumatic and neoplastic. J Ultrastruct Res. 1965;12:611-623.

26. Hammerschlag P.E., Schuknecht H.F. Transcanal labyrinthectomy for intractable vertigo. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;107:152-156.

27. Chen D.A., Linthicum R.H., Rizer F.M. Cochlear histopathology in the labyrinthectomized ear: Implications for cochlear implantation. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:1170-1172.

28. Lambert P.R., Ruth R.A., Halpin C.F. Promontory electrical stimulation in labyrinthectomized ears. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:197-201.

29. Kveton J.F., Abbott C., April M., et al. Cochlear implantation after transmastoid labyrinthectomy. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:610-613.