CHAPTER 7 TRAM Flap Variations in Breast Reconstruction

Summary/Key Points

Patient Selection

Patient selection as in other surgical procedures is of critical importance in the success of breast reconstruction and in particular in the area of autologous breast reconstruction. Carl R. Hartrampf who developed and popularized the TRAM flap (originally termed by him as the transverse abdominal island flap) developed a strict criteria for patient selection that included patient risk factors as well as surgeon experience.2

Once it has been determined that the patient is a candidate for breast reconstruction and has the desire and realistic expectations of what this involves, a more thorough evaluation of the patient can proceed for surgical repair.3,4 The risk factors that keep coming up in studies as most significant include obesity, a strong smoking history, significant metabolic or cardiovascular compromise and a history or intention of using radiation therapy to the breast cancer site. These risk factors need to be considered individually and in combination in order to make a final decision whether breast reconstruction should be performed and what type is most appropriate. This chapter will concentrate on variations of the traditional TRAM flap that can in certain situations improve the chance of a successful outcome.

Indications

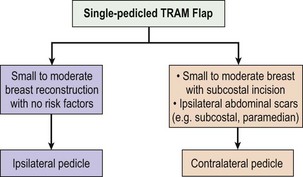

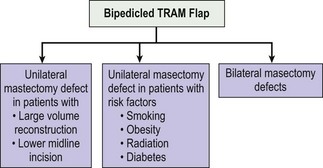

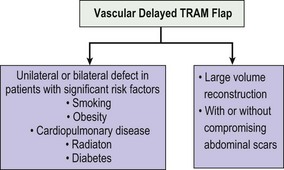

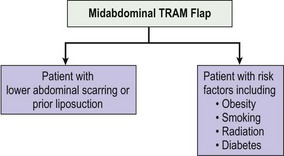

TRAM flap reconstruction can give a very satisfying outcome to the patient who has recently experienced the shock and hardship of a diagnosis of breast cancer. It does however require a considerable investment of time and effort on the part of the patient and the surgeon in order to achieve optimal results. The TRAM flap can also be used for other forms of chest reconstruction resulting from tumor excision or congenital problems such as Poland’s syndrome. It has been used very effectively based on the more robust inferior epigastric pedicle for pelvic and perineal reconstruction due to tumors, trauma, and other causes requiring a large volume of well vascularized tissue. The algorithmic flow charts in Figures 7.1, 7.2, 7.3 and 7.4 show the indications for the TRAM flap and its variations based on morphologic and treatment characteristics.

The most common indication for TRAM flap reconstruction is for a patient with breast cancer who will undergo or has undergone some form of mastectomy. This brings up the issues of immediate or delayed reconstruction which has again become a timely concern with the increasing use of adjuvant radiation therapy for breast cancer. Many studies over the years have shown that immediate reconstruction is a very good option.5 It does not add to the oncologic risks to the patient whether a traditional mastectomy or the increasingly popular skin-sparing mastectomy is performed.6,7 It also permits the surgeon to perform an excellent reconstruction knowing how much breast tissue and volume have been removed, working with native tissues unaffected by scar and contracture, and having a three-dimensional image of the needs for reconstruction. It also permits the patient to recover more quickly overall from the ablative and reconstructive procedures. A psychological benefit in not experiencing a loss of the breast has also been noted, although there are recent counter-arguments in this regard.7 However if post-mastectomy radiation therapy is indicated this will adversely affect the aesthetic outcome of the reconstructive procedure. This has been shown in cases of immediate and even delayed reconstruction.8 The major problem arises when the decision for radiation therapy is determined after the operation when the final pathology of the specimen is determined. This usually occurs about one week after the mastectomy procedure. Several centers will prescribe delayed reconstruction in the patients with a high risk or a high potential for post-mastectomy radiation therapy. At times, reconstruction is temporized by placing a tissue expander in the mastectomy pocket that will be removed after radiation therapy or at the time of the delayed TRAM flap reconstruction.9

Other contraindications for TRAM flap reconstruction are significant systemic disease such as cardiovascular and respiratory problems as well as insulin-dependent diabetes. Hartrampf included insulin-dependent diabetes as one of his significant risk factors. Other groups have not placed as much importance with this.10 I personally have experienced some significant infectious complications in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes and so I am particularly cautious in these patients.

Morbid obesity and smoking have been shown in several studies to be significant risk factors in all forms of breast reconstructions including the TRAM flap.11,12 Variations of the TRAM flap need to be considered in these cases. In the morbidly obese, a midabdominal TRAM flap, a delayed or a double-pedicled TRAM flap may be indicated if it is decided to do any surgery at all. Similarly, in a chronic smoker or one that has recently quit, these TRAM flap variations may also be useful. All attempts, of course, should be made for weight reduction and cessation of smoking prior to performing autologous breast reconstruction.

The experience and comfort level of the surgeon and the surgical team is an important factor in the final indication and decision for a particular type of breast reconstruction. The relative ease and decreased time of performing a TRAM flap makes it a most desirable method of reconstruction. However the surgeon should discuss the various options available in an honest and humble manner with the patient prior to making the final decision. Our understanding of the vascular supply of the TRAM flap is based on a great number of anatomical studies. The more recent classification of Ninkovic et al has refined our understanding of the zones of perfusion. This classification places more importance on the ipsilateral perfusion than the older Hartrampf classification that assigned greater importance across the midline (see Fig. 7.5).

Operative Technique

Preoperative preparation

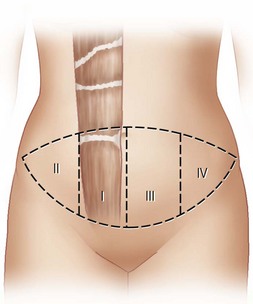

The preoperative preparation of the patient should be well structured and thorough. The amount of time and effort that goes into this preparation will reap benefits intraoperatively as well as in the postoperative period. Any imaging or non-invasive vascular studies, such as laser Doppler flow studies, or computerized tomography (CT) angiogram13 can be conducted preoperatively in order to get a good assessment of the vasculature of the lower abdomen and chest. This is not a substitute for careful operative dissection but can be useful in patients with risk factors that may also include previous scars on the abdomen. Preoperative marking is very important and should be done with the patient in a standing position. Scars of the abdomen are noted; they may include an upper or lower midline scar, appendectomy scar, paramedian scar, or a Pfannenstiel incision. All of these will impact on the type of TRAM flap that will be proposed as well as the incision of the flap. For instance, a lower midline incision may dictate a double-pedicled TRAM flap if a large volume of tissue is needed for reconstruction. The size of the contralateral breast is also taken into consideration. If any modifications are going to be made during the procedure or in a subsequent operation, this also needs to be taken into account. If it is an immediate reconstruction, the size and weight of the mastectomy specimen will be readily available. If it is a delayed reconstruction, it is useful to ascertain the size and weight of the prior mastectomy specimen. This was a very important piece of information to Hartrampf in deciding and predicting the amount of tissue needed for reconstruction. The midline of the abdomen from the xiphoid to the pubis is drawn. A lenticular or transverse elliptical pattern is then drawn on the lower abdomen. An attempt to establish symmetry on both sides is made. The anterior–superior iliac spines are delineated and used in the markings. A pinching of the lower abdominal tissue in order to get an idea for closure is then performed. Adjustments are made according to the ability to be able to close the abdominal wound once the flap has been raised.

The patient is placed in a supine position and general endotracheal anesthesia is induced. A Foley catheter is placed and checked to be in good working condition. Sequential compression devices are now applied to both lower extremities. If the patient is at high risk for DVT or pulmonary embolus, prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin or other indicated prophylactic drugs are given. Guidelines that include a list of risk factors should be followed to help in preventing thromboembolic disease.14 Blood is screened but not cross-matched for possible transfusion which has become rare in ablative and reconstructive breast procedures.

Surgical technique

Variation I: double-pedicled TRAM flap

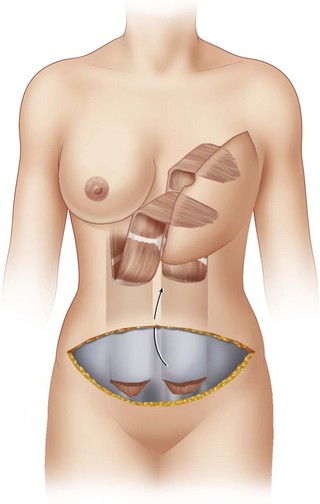

The operative technique for a single-pedicled and double-pedicled TRAM flap (DPTF)15 reconstruction initially is similar. Since the DPTF is much better vascularized, a larger flap can be drawn on the abdomen as both rectus muscle pedicles will be used (see Fig. 7.6). The indications for a double-pedicled TRAM flap for single breast reconstruction may be similar to those for free tissue transfer. Often there is a need for a larger volume of well-vascularized tissue for reconstruction, due to a larger defect on the mastectomy side or a larger contralateral breast. Similarly, there may be causes of impaired blood supply such as a history of smoking, radiation to the chest, or scars that have impaired the circulation distal to their sites. Obese patients generally have unpredictable blood supply and are also at risk for decreased perfusion and flap ischemia; many times they have long torsos and a significant lower abdominal pannus. In these cases a midabdominal position to the TRAM flap may be preferred.

Closure of the donor site

At this point I address the position of the neoumbilicus. I measure its location manually or with a Pitanguy flap demarcator.16 For this I have stapled the central portion of the flap in order to obtain the proper position of the umbilicus. I then make a vertical incision or remove a small vertical ellipse at the site of the new belly-button. I make no attempts at fancy geometric designs as I think this is not necessary. I then remove the staples in the central portion of the flap and I complete the neoumbilical dissection. I remove a layer of fat and Scarpa’s fascia from around this area in order to aid in future contour. Then, using four 3-0 Monocryl fascial sutures I grab the fascia at the base of the umbilicus and then the dermis of the stalk and exit the suture through the neoumbilical hole. I place these sutures at four points on the clock, 12, 3, 6, and 9. When I close the abdominal wall I will then place the suture in the dermis of the abdominal opening. This has the effect of cinching down the dermis around the new umbilical stalk towards the fascia, producing a nice aesthetic ‘innie’ belly-button. On further closing the abdominal wall, I often will use plication or quilting stitches. These will aid in relieving tension on the abdominal wall flap and the incision line as well as possibly decreasing the chance of seroma.17 The final closure of the abdominal wall is now performed from lateral to medial in order to avoid dog-ears. If some fullness or dog-ear does remain, this will be used at a later time when the nipple–areola reconstruction is performed. The fascia and the skin at the incision site are now closed in layers using a 2-0 and a 3-0 Monocryl suture. If the closure is well approximated, I will then use Dermabond for the skin; otherwise, I will use a 4-0 Monocryl in an intradermal running stitch technique. More recently the use of barbed sutures have been used to facilitate closure.

Shaping of the breast

Close attention is now directed to evaluating the flap and the shaping of the new breast. The more care and effort that is spent on this phase of the procedure will determine the quality of the final result. Evaluation of the flap is performed and removal of poorly vascularized segments is now made. If the flap does not look good in color, capillary refill, bleeding at the edges, etc then again a decision for supercharging or possible conversion to free tissue transfer needs to be made. Fortunately, the double-pedicled TRAM flap variation is a very well-vascularized flap since the zones of perfusion are essentially zones #1 and #2 only.10

Variation II: vascular delay of the TRAM flap

The decision to perform a delay of a single-pedicled TRAM flap or rarely of a DPTF is done in order to assure a better and more extensive capture of the flap’s blood supply. This was well demonstrated by the anatomic vascular studies conducted by Taylor et al.18,19 This TRAM flap variation may be necessary in cases where a large contralateral breast requires a large volume of flap tissue for reconstruction. However, it is more commonly used in patients with one or more risk factors which include obesity, a significant smoking history, and a history of radiation to the chest. Patients with scars on certain areas of their abdomen may also dictate the need for a delayed procedure in order to enhance flap viability and sometimes to improve or test the circulation of certain abdominal wall segments.

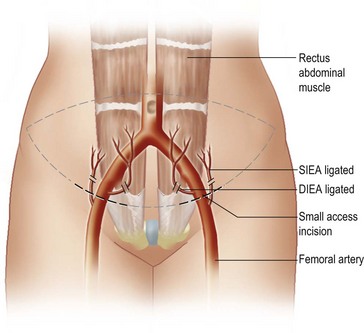

There are essentially two methods used to delay a TRAM flap. One method originally described by Taylor et al20 and widely utilized by Codner and colleagues21 consists of dividing the superficial and deep inferior epigastric vessels on both sides; then 7–14 days later the patient is taken back to the operating room where the definitive reconstructive procedure is performed (see Fig. 7.7). The division of the superficial and deep inferior epigastric vessels is performed through a small lower abdominal incision. It can also be performed by completing the lower abdominal incision thereby providing much broader exposure. Use of a laparoscope or an appropriate endoscope has also been described, but I do not find this to be very useful as the procedure itself is simple and straightforward. It is important that the deep inferior epigastric vessels be ligated as close to their takeoff from the iliac vessels as possible. The deep inferior epigastric vessels commonly bifurcate early and if only one of the vessels is ligated, it may not produce a significant delay as the other vessel may still be perfusing the lower portion of the rectus muscle. The other advantage to this is that a long vascular leash will be available in case it becomes necessary to perform microvascular anastomoses of the flap in case of significant ischemia. The superior aspect of the flap is left intact at the initial delay procedure.

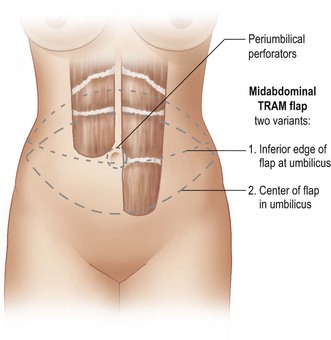

Variation III: midabdominal TRAM flap

In 1988 Slavin and Goldwyn described the mid-abdominal rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap for moderate to large post-mastectomy breast reconstruction.22 The main advantages included increased vascularity and improved abdominal wall integrity because the rectus fascia below the arcuate line was not violated. The increased vascularity has been documented by several authors including the seminal work of Taylor et al that showed the primary vascular angiosomes of the superior epigastric artery system.20 In subsequent studies the midabdominal TRAM flap has been shown to be valuable in patients with increased risk factors, in particular morbid obesity.23 The flap in these patients is particularly of use because they tend to have a long torso and an excessive lower abdominal pannus. Although the incision lies higher on the abdomen than in the traditional TRAM flap, there are several advantages to this variation (see Fig. 7.8). These advantages include:

The approach and preparation of the patient is similar as in other TRAM flap reconstructions. The patient is placed in a supine position. Doppler examination in order to identify the most appropriate perforating vessels is again conducted. The area of flap selection is then evaluated with the patient preferably in a standing position and then once again evaluated with the patient in the supine position in order to ascertain volume and closure considerations. In most situations the umbilicus will lie somewhere in the middle or lower portion of the flap and the inferior incision should lie at or just above the arcuate line. This is estimated at or just below the anterior superior iliac spines. The decision is then made whether to perform a single-pedicled or double-pedicled flap. If a single-pedicled flap is chosen, the decision is then made whether to use an ipsilateral or a contralateral flap. We have mentioned in other parts of this chapter that we prefer the ipsilateral flap due to better positioning of the pedicle and in our hands a sense of better vascularity.24 However, these decisions should also be made based on the characteristics of the particular patient including the Doppler or preoperative imaging evaluations.

1 Sigurdson L, Lalonde DH. MOC-PSSM CME article: breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1-12.

2 Hartrampf CR. Hartrampf’s breast reconstruction with living tissue. Norfolk, VA: Hampton Press; 1991.

3 Reavey P, McCarthy CM. Update on breast reconstruction in breast cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:61-67.

4 Miller MJ. Immediate breast reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1998;25:145-156.

5 Carlson GW, Bostwick J3rd, Styblo TM, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy. Oncologic and reconstructive considerations. Ann Surg. 1997;225:570-575.

6 Harcourt DM, Rumsey NJ, Ambler NR, et al. The psychological effect of mastectomy with or without breast reconstruction: a prospective, multicenter study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1060-1068.

7 Spear SL, Ducic I, Low M, Cuoco F. The effect of radiation on pedicled TRAM flap breast reconstruction: outcomes and implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:84-95.

8 Kronowitz SJ, Hunt KK, Kuerer HM, et al. Delayed-immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:1617-1628.

9 Jones G. The pedicled TRAM flap in breast reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 2007;34:83-104.

10 Spear SL, Ducic I, Cuoco F, Taylor N. Effect of obesity on flap and donor-site complications in pedicled TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:788-795.

11 Spear SL, Ducic I, Cuoco F, Hannan C. The effect of smoking on flap and donor-site complications in pedicled TRAM breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1873-1880.

12 Rozen WM, Phillips TJ, Ashton MW, et al. Preoperative imaging for DIEA perforator flaps: a comparative study of computed tomographic angiography and Doppler ultrasound. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:9-16.

13 Davison SP, Venturi ML, Attinger CE, Baker SB, Spear SL. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in the plastic surgery patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:43E-51E.

14 Wagner DS, Michelow BJ, Hartrampf CRJr. Double-pedicle TRAM flap for unilateral breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:987-997.

15 Pitanguy I. Evaluation of body contouring surgery today: a 30-year perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1499-1514.

16 Pollock H, Pollock T. Progressive tension sutures: a technique to reduce local complications in abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2583-2586.

17 Boyd JB, Taylor GI, Corlett R. The vascular territories of the superior epigastric and the deep inferior epigastric systems. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:1-16.

18 Moon HK, Taylor GI. The vascular anatomy of rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flaps based on the deep superior epigastric system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:815-832.

19 Taylor GI, Palmer JH. The vascular territories (angiosomes) of the body: experimental study and clinical applications. Br J Plast Surg. 1987;40:113-141.

20 Codner MA, Bostwick J3rd, Nahai F, Bried JT, Eaves FF. TRAM flap vascular delay for high-risk breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1615-1622.

21 Slavin SA, Goldwyn RM. The midabdominal rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap: review of 236 flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81:189-199.

22 Gabbay JS, Eby JB, Kulber DA. The midabdominal TRAM flap for breast reconstruction in morbidly obese patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:764-770.

23 Clugston PA, Gingrass MK, Azurin D, Fisher J, Maxwell GP. Ipsilateral pedicled TRAM flaps: the safer alternative? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:77-82.

24 Holm C, Mayr M, Hofter E, Ninkovic M. Perfusion zones of the DIEP flap revisited: a clinical study. PRS. 2006;117:37.