CHAPTER 6 TRAM Flap Breast Reconstruction

Introduction

Breast reconstruction after mastectomy had its primitive beginning with an implant placed subcutaneously in a delayed procedure. The concept of immediate reconstruction was rejected for numerous unsubstantiated reasons, notably that the patient should live with the deformity and that early cancer recurrence would be masked by the reconstruction. Goin and Goin1 advocated immediate reconstruction and emphasized the added benefit of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy when appropriate. Many specialists who could potentially refer their patients for reconstruction did not because of these unfounded concerns. In the late 1970s, musculocutaneous flaps were introduced, offering first the latissimus dorsi.2 Several years later, Hartrampf et al3 presented the rectus abdominis procedure which offered completely autologous reconstruction. These new techniques, together with tissue expanders, now achieved superior aesthetic results with a high degree of reliability. Despite these facts, convincing the oncologic surgeons to offer their patients delayed or immediate reconstruction was very difficult. With slow acceptance of delayed procedures, it took much longer for the immediate procedure to be recognized. Today the surgical armamentarium of flaps and tissue expander/implants makes the prospects of mastectomy for patients much easier to accept. For surgeons recommending the option of breast conservation versus mastectomy, the prospect of a satisfactory aesthetic result makes mastectomy more acceptable, if indicated. This includes those patients with small breasts or tumors located in the upper quadrants where the aesthetic result after lumpectomy and radiation often produce less than ideal results.

Indications

The decision for TRAM reconstruction depends upon the patient’s appropriate anatomy and medical condition. Significant obesity and/or an associated pannus of redundant skin may compromise the circulation to the abdominal wall or TRAM. Abdominal wall scars may compromise the circulation of the abdominal skin flap resulting in necrosis and delayed healing.4 The subcostal scar resulting from an open cholecystectomy is associated with division of the rectus muscle precluding its use as a pedicle on that side. A modification of the skin incision on the right abdomen to include the subcostal scar with the skin island placed higher eliminates the problem of an ischemic area below the scar, a potential cause of abdominal flap necrosis. This modification does not interfere with developing a satisfactory left-sided pedicle.5 Vertical midline scars do not allow use of tissue across the scar unless a bilateral pedicle is employed for unilateral reconstruction. Recently, Mustoe has demonstrated that a delay procedure allows survival of tissue across a vertical midline scar with a unilateral pedicle.6 Suprapubic scars do not pose a problem to the blood supply of either donor site or the TRAM musculocutaneous unit. With a large percentage of patients having undergone prior gynecologic procedures, the major problem encountered has been a more technically difficult dissection due to scarring. In one case, bowel adherent to the rectus muscle in an unrecognized midline infraumbilical hernia required a segmental small bowel resection when the gut wall was injured during a difficult dissection. A right lower quadrant appendectomy scar limits the use of tissue lateral to the scar or favors the use of a left sided pedicle as an alternative. Subjects who are very thin are still viable candidates if they have adequate redundant skin to create a TRAM island and allow closure of the donor site. Here, a prosthesis may be added immediately or at the time of nipple–areola reconstruction, which is the author’s preference.

Those patients with significant lumbosacral disease, that is, spondylolisthesis, are thought to be further compromised if the rectus muscle is sacrificed. Severe asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may compromise the postoperative recovery, but do not contraindicate the procedure. Ischemic heart disease may preclude a long surgery and anesthesia. Cardiac decompensation is a pertinent consideration for patients who have received prior treatment with cardiotoxic chemotherapeutic agents. Insulin-dependent diabetics have an increased risk of complications in general, but of particular concern is the viability of the abdominal wall where ischemia of the flap may result in fat or skin necrosis and wound dehiscence. Similar potential problems apply to smokers7 and obese patients.8

The choice of a pedicled TRAM over other autologous methods of reconstruction or prosthesis-based techniques depends upon many objective factors as described above. The subjective reasons to choose a particular procedure often involves the patient, referring oncologic surgeon or other healthcare provider. Experience with other patients, those of friends or family also often play a role in decision making. Because autologous reconstruction arguably offers the best result, it is the author’s first choice on the reconstructive ladder. Likewise, immediate reconstruction should be considered unless postoperative radiation therapy to the chest wall is certain or there is a possibility that a contralateral mastectomy is considered but refused by the patient or is not practical at the time. A tissue expander may be placed as a temporary method of preserving the mastectomy flaps as a spacer and leave the option open for later autologous reconstruction.9 Genetic testing has significantly increased the number of patients opting for a prophylactic mastectomy of the opposite breast when diagnosed with cancer. The importance of family history in BRCA negative patients has also made prophylactic uni- and bilateral mastectomy and reconstruction a common occurrence.10 Likewise, those patients with strong family history, positive genetic markers or concerns about cancer detection are presenting for bilateral mastectomy without a cancer diagnosis.11–13 Because the abdominal donor site can only be used once, risk of future disease in the opposite breast must be considered as part of the treatment options and informed consent.

Planning mastectomy incisions is a collaborative effort between the oncologic and reconstructive surgeon to consider the many options. The position of the tumor and its relation to the nipple–areola is most important as the skin incision will be determined by their location. Many surgeons will include the biopsy site in the skin incision leading to additional skin flap sacrifice. The concept of skin sparing mastectomy has many interpretations. Preservation of the breast skin usually facilitates better aesthetic outcomes. When there is enough skin to allow a completely de-epithelialized TRAM island, minimal scarring usually results and there is no mismatch of skin color or contour. A transversely oriented scar can later be disguised if the nipple reconstruction punctuates it. Similarly, when only the nipple–areola is sacrificed, the scar is minimal as reconstruction of the nipple–areola will completely obliterate most or all of it. If the breast is large enough and the tumor position allows preservation of the upper breast skin, a Wise pattern (keyhole) mastectomy may be employed.14 This approach allows contouring to reduce lateral fullness and very acceptable incision placement. The secondarily reconstructed nipple can usually be placed at or near the apex of the vertical limb of the inverted ‘T.’ A vertical mammaplasty pattern may also be useful in a skin sparing mastectomy.15,16

Operative Technique I: Planning

Vascular anatomy

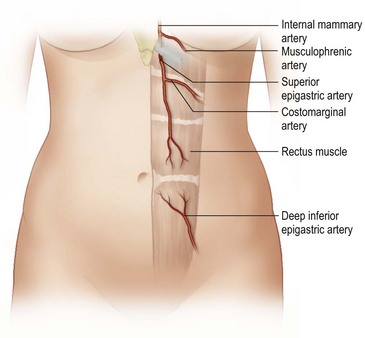

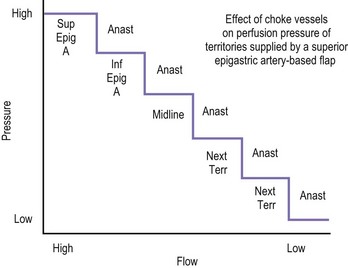

The design of the cutaneous component of a pedicle flap must take advantage of the best blood supply while utilizing the most satisfactory tissue to create a breast mound. The internal mammary artery descends subcostally dividing into the musculophrenic and deep superior epigastric branches. The musculophrenic sends branches to the intercostal vessels. This costomarginal anastomotic circulation is an alternate one when the internal mammary is divided as a result of previous surgery. The deep superior epigastric artery emerges under the medial costal margin and enters the deep surface of the muscle with its accompanying veins. The vessels course within the body of the muscle. Above the level of the umbilicus, the vessels become a web of choke vessels, which anastamose with the vascular supply from the deep inferior epigastric system.17 Since the deep inferior epigastric artery that branches from the internal iliac is the dominant pedicle, there is circulatory compromise when the artery and its two venae comitantes are divided to allow pedicle transfer. This is because the skin island is located over the angiosome of the deep inferior epigastric artery and veins. The venous valves prevent flow superiorly until dilatation secondary to venous congestion renders them incompetent (Fig. 6.1). Understanding the flow dynamics within the muscle and subcutaneous components of the flap are best explained in Moon and Taylor’s diagrammatic representation of the ‘staircase effect’ (Fig. 6.2) Venous return is compromised more often than arterial and is manifested as venous congestion. When flap circulation is compromised, a satisfactory solution is decompression of one of the veins. This maneuver is described later in this chapter. Moon and Taylor18 studied the rectus circulation and describe three patterns of supply from the deep epigastric artery. The most common type branches into two vessels just below the arcuate line. The inferior epigastric pedicle most often enters the deep side of the muscle from the lateral side. Perforating vessels are found in two rows just medial and lateral to the edges of the rectus fascia. There are no perforators below the arcuate line. The skin overlying the rectus muscle is supplied by perforators which pierce the fascia and arborize within the subcutaneous fat. These perforating vessels are largest in number in the periumbilical region and are a prime consideration in designing the skin island to include this region. Slavin19 designed a skin island, which is centered above and below the umbilicus. While this design may result in better arterial supply, it may not allow the advantage of utilizing the best subcutaneous tissue and may leave too short a pedicle to allow adequate rotation. This design results in a surgical scar higher on the abdominal wall, which is more noticeable, thus less desirable.

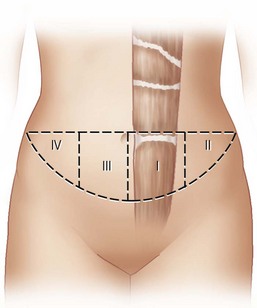

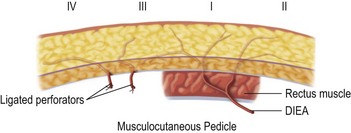

The available skin and fat are considered in four vascular zones (Fig. 6.3). They are numbered in decreasing order of blood supply flow: I–IV. Zone I lies directly over the muscle and has the best circulation with zone II lateral to zone I on the ipsilateral side. Across the midline, zone III has decreased pressure and as a result, its viability is often questionable and must be carefully assessed intraoperatively. Zone IV should not be considered as its viability is always poor. Some authors have labeled zone II as the segment across the midline and zone III ipsilateral next to zone I, but that implies a misleading stepwise progression of blood supply and viability. When a bilateral procedure is performed, each flap is composed of zone I and II. The impact of a vertical infraumbilical scar is discussed earlier.

Operative Technique II: Surgical

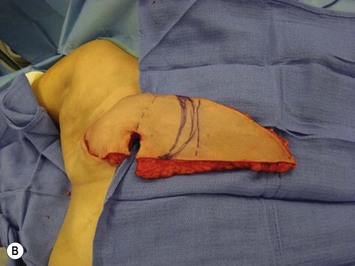

Unilateral procedure (Figs 6.4–6.6)

It is important that the operating table can be flexed to facilitate abdominal wall closure and that it is padded appropriately for the length of the procedure to prevent undue pressure on bony prominences. Sequential compression devices, a catheter in the urinary bladder, and antibiotic prophylaxis are essential. Pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis must be considered for high risk patients.20,21

A transverse incision is made, crossing in a curvilinear manner from each end of the transverse incision across the suprapubic region curving inferiorly. This dissection is taken to the rectus and external oblique fascia. The side opposite the rectus muscle pedicle is then dissected from lateral to medial along the external oblique and rectus fascia. As the perforating vessels are encountered, the larger ones are cross-clamped and ligated. Next, the umbilicus is incised circumferentially and dissected to the fascia, preserving its pedicle. Attention is then turned to the upper edge of the flap. A clamp is placed on the cuff of rectus sheath medially and the skin/fat flap dissected to that point around the umbilicus. The rectus sheath is then incised medially along the entire vertical length of the flap. On the ipsilateral side, a traction suture is placed through the skin and subcutaneous fat. Using this to elevate the flap, the dissection proceeds medially to the lateral border of the rectus fascia. Here, a clamp is placed on the cuff of rectus sheath superiorly and the dissection carried through the rectus sheath dividing it from the upper edge of the flap to the lower border of the skin island. Because of the anatomy of the muscle, the incision curves medially as the dissection proceeds inferiorly. The anterior rectus sheath is then incised along the lower edge of the flap, connecting the medial and lateral incisions. Blunt finger dissection is then used to separate the deep surface of the muscle from the underlying preperitoneal fat. The anterior rectus sheath is separated from the muscle inferiorly to enlarge the space. An Army-Navy retractor is then placed under the muscle and insulated from the surrounding skin by placing laparotomy pads under both ends. The muscle is then divided with electrocautery. The deep inferior epigastric pedicle is usually identified at this time, entering the muscle’s deep surface from the lateral side or in the middle. The pedicle is dissected to the first branch inferiorly, and divided. Double ligatures are placed on the inferior end. If the pedicle is encountered while dividing the muscle, it is similarly ligated. It is advantageous to leave the pedicle long, so that if there is vascular compromise, adjunctive vascular procedures will be easier to accomplish. The cutaneous portion of the musculocutaneous unit is cumbersome because of its size. Thus, it may be helpful to resect through the middle of zone III at this time. The rectus muscle is now dissected from the posterior rectus sheath, taking care to avoid avulsing the perforating vessels. The intercostal neurovascular bundles are divided between clamps and ligated or cauterized. Ligatures are preferable on the flap to reduce thermal trauma from the electrocautery. Fig. 6.7 demonstrates the cross-sectional anatomy of the musculocutaneous unit.

Attention is returned to the abdominal wall. This important step in maintaining functional integrity is discussed by Kroll and Marchi22 and critiques by Nahai.23 The rectus fascia is repaired with permanent figure of eight sutures from the costal margin to the pubis. Care must be taken to include the internal and external oblique aponeuroses in the lateral half of fascia repair. A large enough opening must be left at the costal margin to avoid constricting the muscle, but at the same time tight enough to avoid a hernia. A centralizing suture is placed on the anterior rectus sheath of the intact contralateral muscle to centralize the umbilicus. This is designed as an ellipse, being widest at the umbilicus and tapering above and below. A supporting prosthetic mesh is now sutured from the umbilicus to the pubis across the rectus fascia repair on the ipsilateral side. 0 Prolene sutures are used to fix the prosthesis to the fascia. Prolene mesh was previously used with success but has been replaced by Ultrapro, which is a less rigid material composed of both absorbable and permanent material. This method of repair maintains abdominal wall contour and reliably prevents bulge/hernia. The patient is then placed in a Trendelenberg position, and the back flexed approximately 20 to 30°. Suction drains are placed and brought out through the lateralmost aspect of the incision. For convention, the left drain is placed inferiorly along the incision, and the right drain along the costal margin. Skin closure is accomplished with 00 PDS sutures for the superficial fascia and 3-0 and 4-0 Monocryl sutures for the subcutaneous and subcuticular repairs, respectively. Alternatively, Insorb staples may be used. The umbilicus is brought out through a frown incision and sutured. A ‘V’ is cut from the inferior aspect of the umbilicus and the frown flap from the abdominal wall is sutured into it. If the patient is moderately obese, or there is concern about the circulation to the abdominal flap, a vertically oriented elliptical incision is made in the abdominal flap to admit the umbilicus.

Bilateral procedure (Figs 6.8–6.10)

Delay procedures

Numerous authors have described delay procedures.24–26 For immediate reconstruction, where timely treatment of the malignancy is so critical, it is not reasonable to consider the additional period required for the delay procedure. The additional procedure and possible additional scars are undesirable. Numerous methods have been advocated, but it is difficult to compare their efficacy. In consideration of the above, this author has declined to use delay procedures.

The congested flap

Some degree of venous congestion occurs in every pedicle flap after division of the vessels but is not sufficient to compromise tissue viability. The discussion of flap circulation in Hartrampf’s text27 states that the compensation of arterial circulation is more rapid than venous when flow reverses after deep inferior epigastric pedicle division.

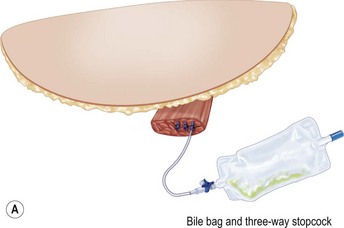

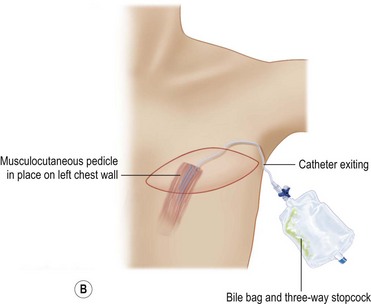

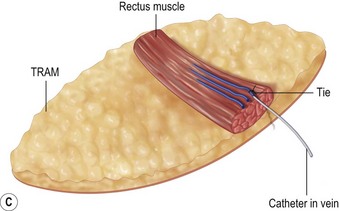

Despite an otherwise ideal candidate and an uncomplicated dissection, the TRAM flap may appear congested. It is not possible to predict which subjects will develop this problem. Venous congestion can occur even before the inferior epigastric pedicle is divided. This early manifestation of congestion is characterized by brisk capillary refill and/or blue or purple mottled appearance of the skin surface. When the congestion occurs after pedicle division, the appearance of the skin is similar to that described above, most apparent in zones III and IV. Inspection of the cut inferior epigastric vessels exhibits engorgement and dark red color. If the congestion is mild, transfer of the flap into the recipient site may resolve or at least improve the condition. Venotomy either before or after flap transfer will usually result in immediate resolution of the congestion. If the problem recurs after bleeding stops, a straightforward solution is to intubate one of the veins with a long angiocath connected to a three-way stopcock28 (Fig. 6.11). If the bleeding is minimal, the stopcock is left open and the angiocath brought out through the mastectomy incision and drained into a bile collection bag. If the flow is great, the three-way stopcock can be used with a syringe and heparinized saline to control the blood loss by periodically opening the flow. In most cases, the flow slows or ceases within several hours. During this time, there is adjustment of flow to increase venous return through the superior epigastric circulation, as vein dilatation renders the valves incompetent. With the flap in place in the chest, abdominal wall closure proceeds. Periodic evaluation of flap circulation is advisable to assess congestion. When resecting the excess tissue, the color of the bleeding at the cut edge also evaluates flap congestion and the bleeding itself relieves congestion, as does bleeding from the de-epithelialized portion of the flap. In deeply pigmented skin, bleeding from the cut dermal or fat edge can also be used to assess congestion. In addition, well oxygenated fat has an iridescent appearance. While venous congestion self corrects over time, a significant degree and duration of congestion will likely contribute to both fat necrosis and an unsatisfactory result due to cell death during the period of hypoxia. This prompts consideration of this technique when significant venous congestion is present. The obvious risk is the associated blood loss and potential need for transfusion.

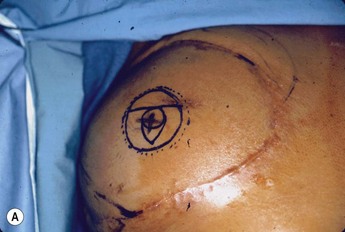

Nipple–areola reconstruction (Fig. 6.12)

This portion of the reconstruction is performed as a secondary procedure, usually in combination with necessary modification of the reconstruction and alteration of the intact breast for symmetry discussed above. Following the description of the skate flap by Little and Noone29,30, the procedure has been refined with minor changes. The site is chosen and marked, sometimes modifying the measured symmetric position to achieve a better appearance. This is performed in a standing position prior to entering the operating room. A 35 mm diameter circle is drawn around the central mark. A line across the equator of the circle is drawn horizontally, or is oriented to avoid a bisecting surgical scar. A 10–12 mm circle is then drawn below the equator centered medial to lateral. If the nipple circle is centered within the areola circle, it will be placed too high. The diameter of the areola is the surgeon’s choice or is measured to match the other breast. This size is ideal for reconstruction. The diameter of the areola can be enlarged with a tattoo if necessary. This is added later. Two lines are drawn, one from each side of the circle curving to meet at the edge of the outer circle. The two wings of the skate are then elevated at a deep dermal level. Centrally, a cut is made into the underlying fat to the equator leaving a ‘keel’ of fat to give bulk to the new nipple. The two wings are brought together and sutured with 5-0 chromic. A second suture is placed several millimeters above and tied. The center of the flap is brought down and sutured to this point with adjustment of the position to achieve the desired projection. If the flaps are sutured together to their apices, a long narrow tubular appearance will result. Next, the corners of the nipple mound are trimmed and closure is completed with the chromic sutures. Since significant shrinking is expected, as much bulk as possible should be incorporated into the flap. However, overzealous deep incisions will result in collapse of the nipple flap and an unacceptable appearance. The upper half of the circle is now de-epithelialized and a full thickness skin graft is supplied after thinning it by excising much of the dermis. The graft may be obtained from a surgical dogear on the breast or abdomen or from a contralateral mastopexy or reduction. If none of these sites are available, non-hairbearing suprapubic or groin skin may be employed. The graft is sutured with interrupted and running 5-0 chromic sutures, a hole cut in the center to admit the nipple and additional sutures placed between the skin graft and nipple flap for stabilization. The skin graft is piecrusted to allow drainage. A donut dressing of Xeroform gauze and plain gauze is fabricated to provide compression of the skin graft but none to the nipple. This dressing is held in place with Steristrips or half inch paper tape and kept in place for 5–7 days. Six months later, the nipple–areola is tattooed to achieve the desired color. Color matching requires artistic ability, patience and experience. The tattoo may also be applied by a professional artist. Reconstructions that avoid a skin graft for the area are simpler to complete but the more irregular surface contour of the piecrusted skin graft together with a tattoo achieve a more realistic result (photographs and diagrams).

1 Goin MK, Goin JM. Psychological reaction to prophylactic mastectomy synchronous with contralateral breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;70:355.

2 Olivari N. The latissimus flap. Br J Plast Surg. 1976;29:126.

3 Hartrampf CR, Schleflan M, Black PW. Breast reconstruction with a transverse abdominal island flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:216.

4 Takeishi M, Shaw W, Ahn C, et al. TRAM flaps in patients with previous abdominal scars. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:216.

5 Weiss P. TRAM flaps in patients with previous abdominal scars. Correspondence and brief communications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:2276.

6 O’Shaugnessy K, Mustoe T. The surgical TRAM flap delay: reliability of zone III using a simplified technique under local anesthesia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1627.

7 Padubidri A, Yetman R, Browne E, et al. Complications of postmastectomy breast reconstructions in smokers, ex-smokers, and non-smokers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(2):342.

8 Greco J, Castaldo E, Nanney LB, et al. Autologous breast reconstruction: the Vanderbilt experience (1998 to 2005) of independent predictors of displeasing outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:49.

9 Fine N, Hirsch E. Keeping options open for patients with anticipated postmastectomy chest wall irradiation: immediate tissue expansion followed by reconstruction of choice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:25.

10 Briasoulis E, Ziogas D, Fatouros M. Prophylactic surgery in the complex decision-making management of BRCA mutation carriers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1788.

11 Wainberg S, Husted J. Utilization of screening and surgery among unaffected carriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1989.

12 Robson M, Svahn T, McCormick B, et al. Appropriateness of breast-conserving treatment of breast carcinoma in women with germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Cancer. 2004;103:44.

13 Metcalfe K, Lubinski J, Ghadirian P, et al. Predictors of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: the hereditary breast cancer study group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1093.

14 Skoll P, Hudson D. Skin sparing mastectomy using a modified Wise pattern. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:214.

15 Young K, Satovsky N. The vertical pattern breast reconstruction for large or ptotic breasts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:2052.

16 Scholz T, Kretsis V, Kobayashi M, et al. Long-term outcomes after primary breast reconstruction using a vertical skin pattern for skin-sparing mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1603.

17 Miller LB, Bostwick J3rd, Hartrampf CRJr, Hester TRJr, Nahai F. The superiorly based rectus abdominis flap: predicting and enhancing its blood supply based on an anatomical and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81:713.

18 Moon H, Taylor I. The vascular anatomy of rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flaps based on the deep superficial epigastric system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:815.

19 Slavin S, Goldwyn R. The midabdominal rectus abdominis mycocutaneous flap: review of 236 flaps. Plast Recosntr Surg. 1988;81:189.

20 Seruya M, Venturi L, Iorio ML, Davison SP. Efficacy and safety of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in highest risk plastic surgery patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1709.

21 Kim E, Eom J, Ahn SH, Son BH, Lee TJ. The efficacy of prophylactic low-molecular-weight Heparin to prevent pulmonary thromboembolism in immediate breast reconstruction using the TRAM flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:9.

22 Kroll S, Marchi M. Comparison of strategies for preventing abdominal wall weakness after TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:1045.

23 Nahai F. Discussion of comparison of strategies for preventing abdominal wall weakness after TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:1052.

24 Hudson D. The surgically delayed unpedicled TRAM flap for breast reconstruction. Am Plast Surg. 1996;36:238.

25 Codner M, Bostwick J. TRAM flap vascular delay for high-risk breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1615.

26 Restifo R, Ward B, Scoutt LM, Brown JM, Taylor KJ. Timing, magnitude and utility of surgical delay in the TRAM flap: part II. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1.

27 Hartrampf C. Hartrampf’s breast reconstruction with living tissue. Norfolk: Hampton Press; 1991.

28 Caplin D, Nathan C, Couper SG. Salvage of TRAM flaps with compromised venous outflow. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:400.

29 Noone B, Little W. Nipple reconstruction with a skate flap. ASPRS annual meeting instructional course.

30 Shestak K, Gabriel A, Landecker A, Peters S, Shestak A, Kim J. Assessment of long-term nipple projection: a comparison of three techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:780.