CHAPTER 10 Training in peripheral nerve blockade

In 1979–1980, anesthesia residents in the USA reported using regional anesthesia techniques in approximately 21% of cases.1 While over the following decade this improved to 29.8%, large differences remained between individual training programs in their ability to deliver training in peripheral nerve blockade techniques.2 A follow-up study in the year 2000 showed a disappointingly small increase in use to 30.2% of cases; an insignificant change.3 Moreover, the vast majority of cases revolve around central neuraxial blockade, with most residents gaining their exposure to peripheral nerve blocks through chronic pain modules. Thus, upwards of 40% of United States residents (registrars) are likely to have received inadequate training in peripheral nerve block techniques. Although there is little supporting published evidence, this picture is likely to be replicated in many other countries. In order to meet this need, there are data to suggest that in the United States alone there is a requirement in the order of 250 trained regional anesthesia experts.4 In order to redress such deficiencies in training, it is apparent that residency programs will need to reappraise not only their core curricula but also their faculty and their core competencies.

Institutional organization

In an effort to move the subspecialty forward in this regard, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia has endorsed a set of guidelines for regional anesthesia fellowship training.5 These guidelines have been developed by a group of regional anesthesiology fellowship directors and other interested parties from across the United States over a number of years. They suggest a method for addressing:

Some of the ‘critical determinants of learning’ have been identified and include:

Programs such as that endorsed by ASRA are required to ensure residents obtain such formal structured training and to minimize factors such as in points (2), (3) and (4). It sets out a template that any institution may adopt and adapt in developing a comprehensive fellowship program (Box 10.1). The remainder of this chapter will, for the most part, deal with the practicalities of imparting skills and the assessment of competencies in these skills.

Box 10.1

Guidelines for Regional Anesthesia Fellowships

A consensus document from the directors of regional anesthesia fellowship programs.

Mission statement:

Program requirements for Fellowship Training in Regional Anesthesia:

Outline:

Fellows must be able to show competency in the following areas:

Skills and competencies

Recommended case numbers

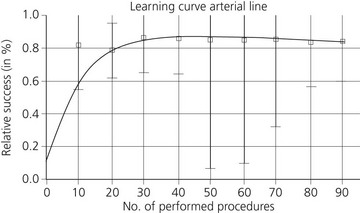

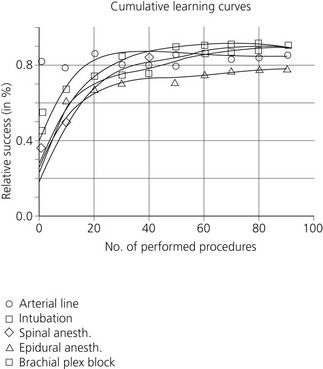

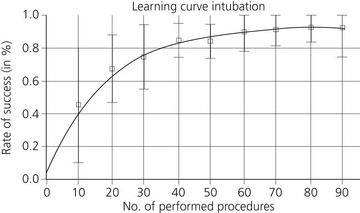

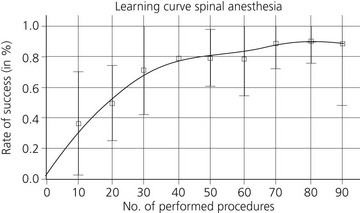

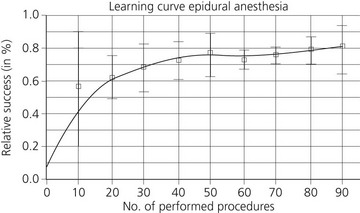

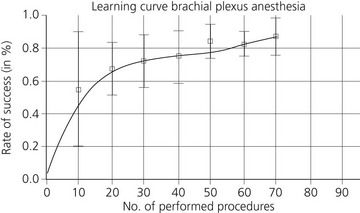

There is broad agreement as to the minimum recommended number of times a resident should perform a procedure in order to reach the requisite standard.7–9 The learning curves for a variety of procedures show a marked improvement of skill after the initial 20 attempts and inter-individual scattering decreases over time (Figs 10.1–10.6).

Figure 10.1 A summary of mean learning curves.

(Konrad C, Schüpfer G, Wietlisbach, Gerber H. Learning manual skills in anesthesiology: is there a recommended number of cases for anesthetic procedures? Anesth Analg 1998; 86: 635–639.)

Figure 10.2 The intubation learning curve.

(Konrad C, Schüpfer G, Wietlisbach, Gerber H. Learning manual skills in anesthesiology: is there a recommended number of cases for anesthetic procedures? Anesth Analg 1998; 86: 635–639.)

Figure 10.3 The spinal anesthesia learning curve.

(Konrad C, Schüpfer G, Wietlisbach, Gerber H. Learning manual skills in anesthesiology: is there a recommended number of cases for anesthetic procedures? Anesth Analg 1998; 86: 635–639.)

Figure 10.4 The epidural anesthesia learning curve.

(Konrad C, Schüpfer G, Wietlisbach, Gerber H. Learning manual skills in anesthesiology: is there a recommended number of cases for anesthetic procedures? Anesth Analg 1998; 86: 635–639.)

Figure 10.5 The brachial plexus anesthesia learning curve.

(Konrad C, Schüpfer G, Wietlisbach, Gerber H. Learning manual skills in anesthesiology: is there a recommended number of cases for anesthetic procedures? Anesth Analg 1998; 86: 635–639.)

Simulation-based training

A variety of simulator models for peripheral nerve blockade have been proposed. These include gel phantoms and turkey leg and pig models.10 Workshop delegates report these to be well suited for training purposes and highly relevant for clinical practice. Workshop delegates, however, are in large part a self-selecting group and simulation-based assessment is still in its infancy. In order to use simulation for high-stakes assessments, such as accreditation, more research and development is required to refine and standardize scenario content, scoring methods, evaluator training, and assessment protocols.11

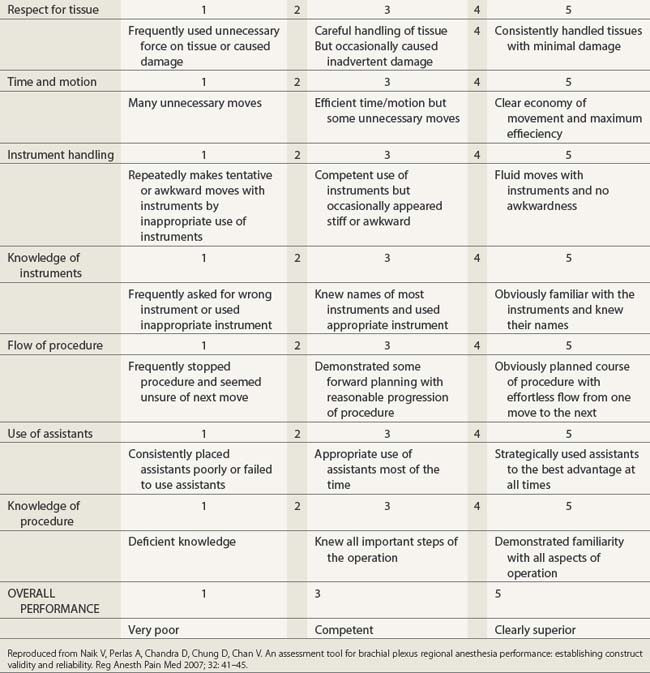

Checklist and global rating scale

Validated global rating systems and a checklist created using a Delphi technique, whereby content validity is arrived at by expert consensus, have been used to assess technical proficiency in the performance of interscalene block.12 Both assessment modalities are capable of reliably discriminating between different levels of training. As objective measures of technical skills, they are feasible and capable of improving the validity and reliability of competency-based assessments (Tables 10.1 and 10.2).

Reproduced from Naik V, Perlas A, Chandra D, Chung D, Chan V. An assessment tool for brachial plexus regional anesthesia performance: establishing construct validity and reliability. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2007; 32: 41–45.

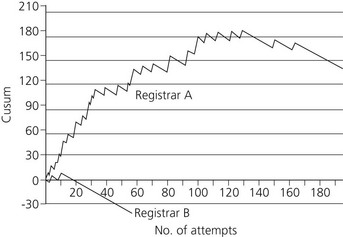

Cusum method

Cumulative sum (cusum) analysis is a statistical method of distinguishing deviations from an acceptable failure rate. It has been used in industry as a method of quality control and more latterly in healthcare, where it has the potential to determine when a resident is proficient in a new technique and as a continuous audit of quality of practice for more experienced clinicians.13–15

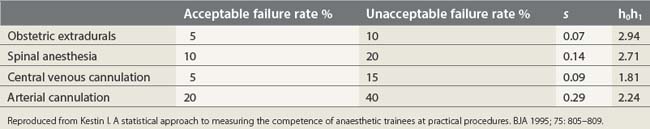

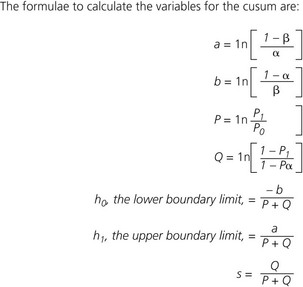

Prior to commencement, suitable acceptable and unacceptable failure rates for the procedure must be chosen (p0 and p1), examples of which are given in Table 10.3. The desired magnitude of the type 1 and type 2 errors (α andβ) must also be chosen and the two boundary limits to the cusum, h0 and h1 are calculated, as is the variable s (Fig. 10.7). The cusum increases by 1−s for a failure and decreases by s for a success. When the cusum breaks through the lower boundary limit (h0) from above then the true failure rate does not differ significantly from the acceptable failure rate (the null hypothesis) with the probability of a type II error equal to β. If the cusum breaks through the upper boundary limit (h1) from below then the true failure rate is significantly greater than the acceptable failure rate with a probability of a type I error equal to α. Further lines are drawn on the graph at 2h1, 3h1 and 4h1 as required, allowing the null hypothesis to be accepted or rejected on further attempts. If the cusum stays between h0 and h1 the observations must be continued, as no statistical inference can be made. A sample cusum chart for obstetric extradural from two anesthesiology residents is shown in Figure 10.8.

Table 10.3 Acceptable and unacceptable failure rates for four procedures (as defined by a consensus of consultants), the values of s and the boundary limits for the cusum

Figure 10.7 The formulae to calculate the variables for the cusum.

(Kestin I. A statistical approach to measuring the competence of anaesthetic trainees at practical procedures. Br J Anaesth 1995; 75: 805–809.)

‘A specialty in transition?’

Peripheral nerve blockade is now a well-accepted method for realizing the clinical and economic benefits of better pain control, ‘fast-tracking’ of patients, improved discharge times, improved physical therapy and improved postoperative cognitive dysfunction scores. Unfortunately, the inherent failure rate it has carried to date, combined with other impediments to its performance in theater, has meant it has been held in lower esteem than generally simple, safe and efficacious general anesthesia.16 The traditional methods used to perform peripheral nerve blockade (transarterial and paresthesia techniques, nerve stimulation) have relied on a sound knowledge of anatomy and surface anatomy. Inherent weaknesses in these approaches are obvious when one considers the range of anatomical variation present in the human population and the limitations in the sensitivity and specificity of nerve stimulation.

The advent of ultrasound has been described as a significant step-change in regional anesthesia.17 As ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia (USGRA) has the potential to produce successful nerve block in all cases, failures will be due to poor operator technique rather than inherent deficiencies of the technique per se. This is an important point to consider, as the requirement to deliver suitably trained practitioners will come with the realization of regional anesthesia’s potential.

While experienced practitioners will learn the techniques from their peers, it behoves the profession as a whole to ensure training in USGRA becomes a core part of all future anesthesiology training. The teaching of these new, yet essential, skills should be included as part of residency training. The proverb ‘see one, do one, teach one’ should not be applied to a core competency such as USGRA, and a number of quality-compromising patterns of behavior can be identified when novices undertake to learn these techniques.18 The incorporation of transesophageal echo (TEE) into mainstream clinical practice has led to a formal process of accreditation and documentation, and so it may be with USGRA.

The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine and the European Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Therapy Joint Committee has now issued recommendations for education and training in USGRA (Box 10.2).19 The document aims to define the scope of practice of USGRA under the following headings:

Box 10.2

I The Ultrasound-guided Regional Anesthesia Coordinator

The Joint Committee recommends that the candidate obtain the following:

II Core competencies for residency training in UGRA

Ultrasound knowledge

Interpersonal/communication skills

Practice-based learning and improvement

III Recommended ultrasound curriculum

Curriculum content: scanning techniques

IV Recommended technique for ultrasound scanning

VI Recommended procedure for correlating ultrasound screen with patient sidedness for patients in prone, supine, and lateral decubitus positions

Adapted from Sites B, Chan V, Neal J, et al. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine and the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy Joint Committee recommendations for education and training in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 40–46.

Acquiring and maintaining expertise

The practical implications of training large numbers of anesthesiology residents and their seniors in USGRA is formidable and it will likely be a number of years before every residency program has the in-house expertise to be able to do this. Advice on training is available from a number of sources (Table 10.4) and there are many workshops that can be currently availed of. However, there is usually no formal accreditation of attained skills.

| UK Royal College of Publications | www.rcr.ac.uk |

| BFCR(05)1 Standards for Ultrasound Equipment | |

| BFCR(05)2 Ultrasound Training Recommendations | |

| British Medical Ultrasound Society | www.bmus.org |

| European Federation of Ultrasound | www.efsumb.org |

| Australian Society Ultrasound in Medicine | www.asum.com.au |

| Association of Cardiothoracic Anaesthetists | www.acta.org.uk |

| British Society of Echocardiography | www.bsecho.org |

| American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine | www.aium.org |

| Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists | www.rcog.org.uk |

Reproduced from Bodenham A. Ultrasound imaging by anaesthetists: training and accreditation issues. Br J Anesth 2006; 96: 414–417.

As the range of procedures likely to be performed by anesthesiologists using ultrasound increases (Table 10.5), it is likely that so too will there be a demand for more comprehensive training to a high standard. Such training will have to enable the practitioner to recognize common pathology and when a referral for further investigation is required (Table 10.6).20

Table 10.5 Ultrasound procedures likely to be conducted by anesthetists

Reproduced from Bodenham A. Ultrasound imaging by anaesthetists: training and accreditation issues. Br J Anesth 2006; 96: 414–417.

Table 10.6 Levels of competence for ultrasound, shortened from Royal College of Radiologists’ guidelines

| Level 1 |

| Level 2 |

| Level 3 |

Note: The boundaries between levels should only be regarded as a guide.

Reproduced from Bodenham A. Ultrasound imaging by anaesthetists: training and accreditation issues. Br J Anaesth 2006; 96: 414–417

Reproduced from Hargett M, Beckman J, Liguori G, Neal J. Guidelines for regional anesthesia fellowship training. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005; 30: 218–225.

Motivation to improve, focus on clearly defined tasks, immediate useful feedback and repetitive deliberate practice strategically guided by an expert instructor are the keys to forming and maintaining expertise.21 Simulation-based training may form an important component in this and USGRA may be particularly suited to this type of training and the on going assessment of expertise.22 It is also likely that the public, government and other regulators will insist on some form of assessment and accreditation. Anesthesiologists have been to the forefront in this type of training and are well placed to affect both the pace and direction of the changes that are required. Funding of simulator-based research to establish valid training content, structure, and scoring metrics is required. Collaboration is necessary with educators, psychometricians, and other specialties. Training of a large cadre of skilled instructors/evaluators and a commitment to large-scale standardized training and assessment of medical students, residents, and experienced anesthesiologists is also necessary.11

1 Bridenbaugh L. Are anesthesia resident programs failing regional anesthesia? Reg Anesth. 1982;7:26-28.

2 Kopacz D, Bridenbaugh L. Are anesthesia residency programs failing regional anesthesia? The past, present and future. Reg Anesth. 1993;18:84-87.

3 Kopacz D, Neal J. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine: Residency training – the year 2000. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:9-14.

4 Brown D. Fellowship training in regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:215-217.

5 Hargett M, Beckman J, Liguori G, Neal J. Guidelines for regional anesthesia fellowship training. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:218-225.

6 Kulcsar Z, Aboulafia A, Hall T, Shorten G. Determinants of learning to perform spinal anaesthesia: a pilot study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25:1026-1031.

7 Kopacz D, Neal J, Pollock J. The regional anesthesia ‘learning curve’: what is the minimum number of epidural and spinal blocks to reach consistency? Reg Anesth. 1996;21:182-190.

8 Kopacz D, Neal J, Pollock J. Residency training in regional anesthetic techniques: is experience with more than 40 attempts necessary? Reg Anesth. 1997;22:205-211.

9 Konrad C, Schüpfer G, Wietlisbach M, Gerber H. Learning manual skills in anesthesiology: is there a recommended number of cases for anesthetic procedures? Anesth Analg. 1998;86:635-639.

10 Raimer C, Birnbaum J, Wauer H, Volk T. A training model for peripheral regional anesthesia techniques. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:65.

11 Weinger M. Experience not equal expertise: can simulation be used to tell the difference? Anesthesiol. 2007;107:691-694.

12 Naik V, Perlas A, Chandra D, et al. An assessment tool for brachial plexus regional anesthesia performance: establishing construct validity and reliability. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:41-45.

13 Kestin I. A statistical approach to measuring the competence of anaesthetic trainees at practical procedures. BJA. 1995;75:805-809.

14 de Oliveira Filho G. The construction of learning curves for basic skills in anesthetic procedures: an application of the cumulative sum method. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:411-416.

15 de Oliveira Filho G. Learning curves and mathematical models for interventional ultrasound basic skills. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:568-573.

16 Sites B, Spence B, Gallagher J, et al. Regional anesthesia meets ultrasound: a specialty in transition. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52:456-466.

17 Hopkins P. Ultrasound guidance as a gold standard in regional anaesthesia. BJA. 2007;98:299-301.

18 Sites B, Spence B, Gallagher J, et al. Characterizing novice behavior associated with learning ultrasound-guided peripheral regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:105-117.

19 Sites B, Chan V, Neal J, et al. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine and the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy Joint Committee recommendations for education and training in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:40-46.

20 Bodenham A. Ultrasound imaging by anaesthetists: training and accreditation issues. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:414-417.

21 Ericsson K. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Academic Med. 2004;79:870-881.

22 Reznick P, MacRae H. Teaching surgical skills: changes in the wind. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2664-2669.