Chapter 55 Tracheostomy for sleep apnea

Tracheostomy historically is the first treatment offered for obstructive sleep apnea. It remains the only surgical option directed at obstructive sleep apnea that uniformly eliminates sleep apnea permanently. Since it was first introduced in 19681 and subsequently reported in several large studies,2,3 newer choices of medical and surgical intervention have reduced the number of people needing a tracheostomy to relieve severe and life-threatening obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

There remain some patients for whom other treatments have been ineffective, intolerant or refused. Current reports4,5 have agreed with the long-term success at maintaining an open upper airway by creating a tracheostomy to reduce morbidity and mortality.

While tracheostomy for obstructive sleep apnea was reported by Kuhlo in 1968,1 Fee and Ward6 described a technique of skin-lined flap tracheostomy to overcome the above complications in the obese patient with obstructive sleep apnea. The goal had been to create a stoma of permanence with a diameter of 8–10 mm.

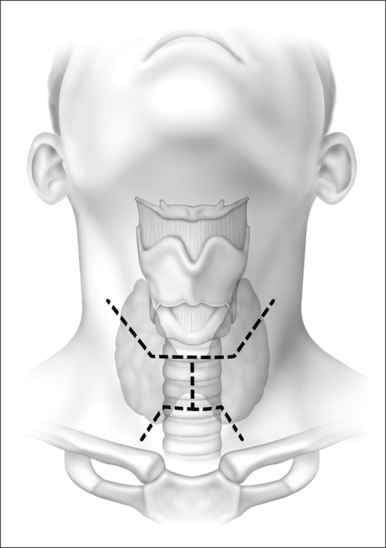

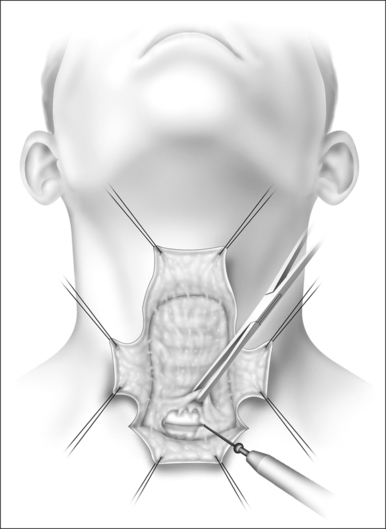

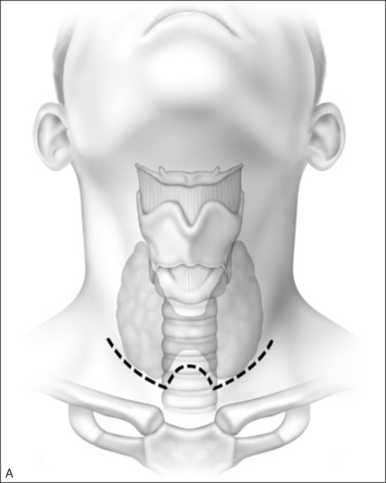

Their plan was to create a series of vertical and horizontal skin incisions which allow easy access to the fibrofatty pad of tissue overlying the muscles from the level of the hyoid bone above to the sternal notch below (Fig. 55.1). This flap elevation includes defatting the skin flaps safely and creating two vertical and two horizontal skin flaps that will be sutured to the trachea mucosa. Defatting and elevating the skin flaps safely with respect to vitalizingthe skin is most important. When elevation is complete, the surgical field is ready for a lipectomy, which is achieved from the level of the hyoid bone often down to the levelof the fifth tracheal ring (Fig. 55.2). The skin flap elevation allows access to perform a hyoidopexy to the mandibleor thyroid cartilage, if indicated, and allows removal of submental fat which will permit the healed patient to maintain an open tracheal lumen without a submental flap occluding the stoma when the head falls to the chest during sleep.

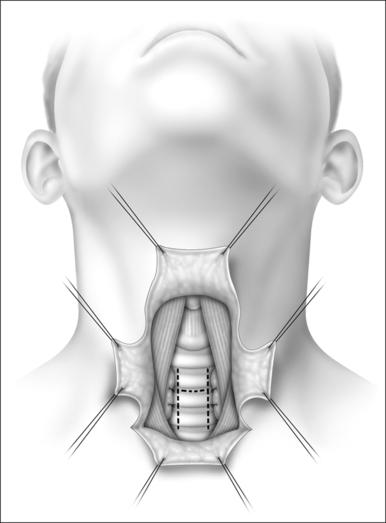

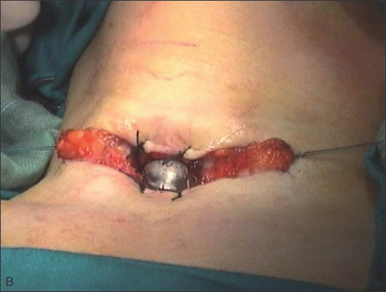

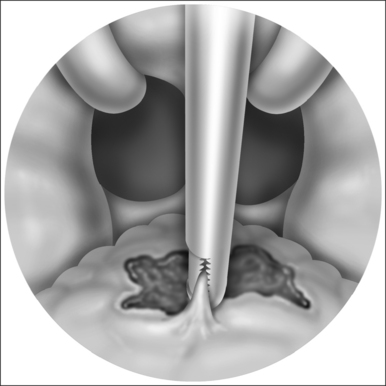

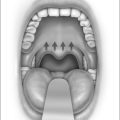

The incision (H-shaped) is made in the trachea with the horizontal limb below ring two (Fig. 55.3). The four skin flaps are then sutured with an inferiorly based flap, which is longer than the superior flap, to allow tension-free opposition of the inferior skin flap with the inferior tracheal flap. The four skin flaps are then sutured with a superior and inferior flap sewn to cartilage that everts into the wound, and the two lateral skin flaps, having been appropriately defatted, are sutured to the lateral tracheal wall.

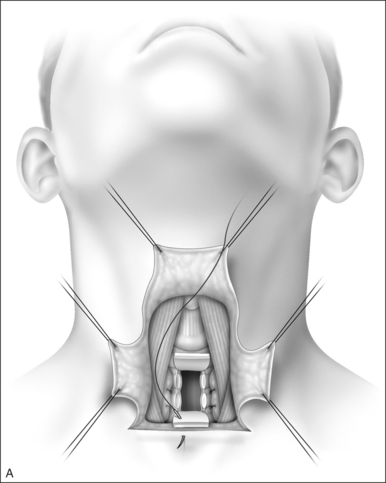

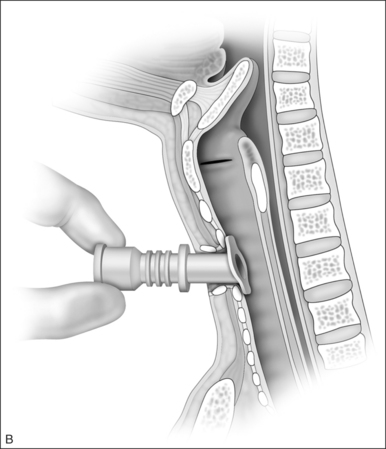

These operations are performed under general endotracheal anesthesia and co-operation with the anesthesiologist is paramount. Extubation is often unnecessary until the skin flaps are all closed, and suction or Penrose drains placed. It is often necessary for the cuff on the endotracheal tube to be deflated intermittently as sutures are placed in the tracheal lumen. This can avoid puncturing the balloon on the tracheostomy tube which requires replacement of the ventilating tube either through the stoma or by reintubating transorally (Fig. 55.4 A&B).

The stoma, when complete, has a 360° mucocutaneous junction and as this heals without skin necrosis or diastasis, minimizes granulation and maintains a cutaneous tracheal lumen. We always complete the procedure with placement of a cuffed tracheostomy tube. This eases control of secretions from the wound, and ensures adequate mechanical ventilatory support can be rendered in the early postoperative period for these patients. They often have significant cardiopulmonary co-morbidity, which may be exacerbated by converting from transoral respiration to transcervical.7

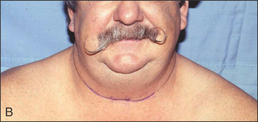

The skin flaps designed as in Figure 55.1 offer viable flaps which reach the trachea with little tension. They allow an open approach to the fibrofatty flap and as described can permit easy access to the level of the mandible and thesubmental fat pad. However, visible scars are created. These may call unnecessary attention to the neck in these patients, who otherwise look unchanged after complete healing of the incisions and when wearing a high-collarshirt (Fig. 55.4C). Many patients create a necklace that includes a tracheostomy occlusal device of silver or gold, and the patient may be complimented by the casual observer for his attractive jewelry.

For some patients we can create a larger and better vascularized skin flap when designed as depicted in Figure 55.5, with a long collar incision, usually placed at a higher level than a routine thyroidectomy skin incision. The center of the flap near the midline is designed so that a thumbnail sized U-shape elevation of the flap is created that will reach to the tracheal lumen. This flap offers similar exposure to the previously described horizontal H skin incision and usually allows skin flaps to be sutured under minimal tension to the mucosa of the trachea. It enhances the vitality of the inferior skin flap because of its broader base. It is this flap and suture line that are usually at greatest risk of dehiscence and necrosis, creating a granulating wound. When healed, a skin-lined inferior flap allows the tracheostomy to sit on a healed epithelial surface and results in fewer patient complaints of malodorous drainage, bleeding during tracheostomy tube change or cleaning, and minimizes stomal stenosis.8–10 Another flap, designed by Claymanand Adams, uses superiorly and inferiorly based rectangular flaps united to an inferiorly based U flap of trachea9 (Fig. 55.4B).

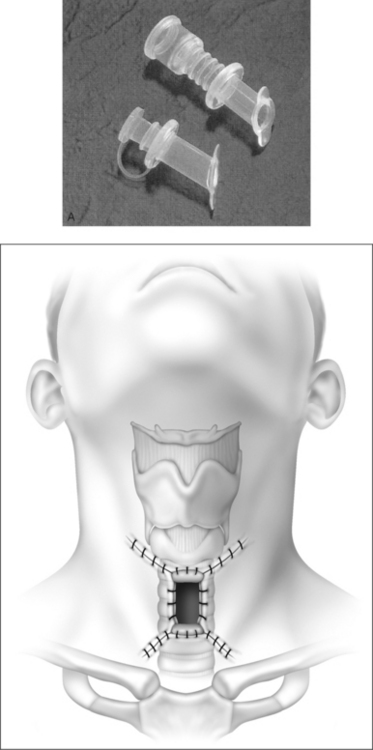

Once complete healing has occurred and the patient is prepared to occlude the tracheostomy tube while active and awake, and to open the lumen only for sleep, we often use an uncuffed plastic (Shiley) or an uncuffed metal (Jackson) tube. We have good success using a Montgomery cannula11 as a replacement stoma vent after tracheal mucosal healing has occurred and the sutures are absorbed or removed. This cannula (Fig. 55.6A&B) has two flanges which grasp the anterior tracheal wall superiorly and inferiorly, and allow a larger tracheal lumen to permit full activity without dyspnea in these patients. They are often active at work and play, and notice increased air hunger with a plugged standard tracheostomy tube. The tube has been designed at an angle of 27° to fit unobtrusively in the lumen. In general, it extends from the skin more than an uncuffed tracheostomy tube which is built without an Ohio adaptor. Many patients learn to extubate themselves, clean the tracheostomy tube and replace it, plugging it during the day so that they humidify their inspired air transnasally. They can communicate without air escape through the tracheostomy stoma, and lead normal, functional lives. The plug is removed at night or during naps so that no obstructive apnea events will occur.

Custom-molded stoma buttons have been made with co-operation from dental prosthodontists and have been useful to patients with a well-healed stoma. We attempted creating a mold to allow multiple stoma button production. We have found little success at creating a perfect size that fits all patients without an air leak, even as the wound heals and the lumen contracts to fit the button scarred into place. Therefore, we have not continued to pursue this approach for daytime stoma occlusion in our population of obstructive sleep apnea patients with tracheostomy. Other physicians and their patients continue to work with personalized stoma stents.

Our success with tracheostomy remains excellent, and our complications with this technique, which minimizes granulation and allows the stoma to remain unsupported in many patients overnight, is exemplary. This is in contrast to tracheostomy without skin lining which always requires a stent in place. Our results4 (Table 55.1) agree with Haapaniemi et al.12 who noted long-term success and no deaths among seven tracheostomy patients followed for 5 years. Our results also agree with those of Partinen.13 He and his co-workers noted no deaths among 33 tracheostomy patients, in contrast to 11 deaths among those who were not treated.14 The series by Thatcher and Maisel followed obstructive sleep apnea patients long term. This series shows similar encouraging results over a range of up to 20 years for 79 tracheostomy patients.4

| No. of patients |

| Male |

| 70 |

| Female |

| 9 |

| Follow-up |

| Mean |

| 8.3 years |

| Range |

| 3 mo–20 y |

| Age |

| Mean |

| 47 y |

| Range 25–70 y |

| Body Mass Index |

| Mean |

| 41 |

| Range |

| 23–64 |

| Respiratory Disturbance Index |

| Range 45–146 |

| Mean 82 |

In conclusion, for patients who are intolerant of mechanical measures or fail upper airway surgery and continue to have severe symptoms or physiologic changes related to obstructive sleep apnea, flap tracheostomy is a reasonable alternative creating a population of alert, awake patients with reduced morbidity and mortality from severe obstructive sleep apnea.

1. Kuhlo W, Doll E, Frank MC. Successful management of Pickwickian syndrome using long-term tracheotomy. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1969;13:1286-1290.

2. Simmons FB, Guillemainault C, Dement WC, et al. Surgical management of airway obstructions during sleep. Laryngoscope. 1976;86:326-338.

3. Weitzman ED, Kahn E, Pollock CP. Quantitative analysis of sleep and sleep apnea before and after tracheostomy in patients with hypersomnia–sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1980;3:407-423.

4. Thatcher GW, Maisel RH. The long-term evaluation of tracheostomy in the management of severe obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:201-204.

5. Kim SH, Eisele DW, Smith PL, et al. Evaluation of patients with sleep apnea after tracheotomy. Arch Otolaryngol. 1998;124:996-1000.

6. Fee WE, Ward PH. Permanent tracheostomy. Ann Otolaryngol. 1977;86:635-638.

7. Sahni R, Blakely B, Maisel RM. ‘How I do it’ – flap tracheostomy in sleep apnea patients. Laryngoscope 1985;95(2):221–3.

8. Maisel RH, Goding GS. Tracheostomy for obstructive sleep apnea: indications, techniques and selection of tubes. Operat Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;2:107-111.

9. Clayman GL, Adams GL. Permanent tracheostomy with cervical lipectomy. Laryngoscope. 1990;100(4):422-424.

10. Campanini A, De Vito A, Frassineti S, Vicini C. Role of skin-lined tracheotomy in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: personal experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2004;24:68-75.

11. Montgomery WW. Silicone tracheal cannula. Ann Otolaryngol. 1980;89:521-528.

12. Haapaniemi JJ, Laurikainen EA, Halme P, Antilla J. Long-term results of tracheostomy for severe obstructive sleep apneasyndrome. ORL Relat Spe 2001;63(3):131–6.

13. Partinen N, Jameson A, Guillame C. Long-term outcome for obstructive sleep apnea patients. Chest. 1988;94:1200-1204.

14. He J, Kryger MH, Zorick FJ, et al. Mortality and apnea index in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1988;94:9-14.

inch (6.35 mm) to secure the tube in place are placed around the neck and secured with one or two fingers laxity between tape and neck skin. Patients with sleep apnea are anticipated to have an active and productive life once sleep apnea has been treated surgically and even with significant co-morbidities, we anticipate an active lifestyle. However, the tracheostomy technique described above does not allow temporary extubation, and under only extraordinary circumstances would allow a tube-free tracheostomy, even for short times during the day or overnight. Therefore, most patients, including many of normal body habitus, who have severe obstructive sleep apnea and have been untreatable with mechanical positive pressure or upper airway surgery are recommended to have a tracheostomy as described below. Most of these patients are severely obese with a Body Mass Index greater than 36 and with sizable adipose tissue between skin and trachea. These people need a more thorough approach to the airway and a better solution to stoma hygiene in what is anticipated as life-long airway and apnea management.

inch (6.35 mm) to secure the tube in place are placed around the neck and secured with one or two fingers laxity between tape and neck skin. Patients with sleep apnea are anticipated to have an active and productive life once sleep apnea has been treated surgically and even with significant co-morbidities, we anticipate an active lifestyle. However, the tracheostomy technique described above does not allow temporary extubation, and under only extraordinary circumstances would allow a tube-free tracheostomy, even for short times during the day or overnight. Therefore, most patients, including many of normal body habitus, who have severe obstructive sleep apnea and have been untreatable with mechanical positive pressure or upper airway surgery are recommended to have a tracheostomy as described below. Most of these patients are severely obese with a Body Mass Index greater than 36 and with sizable adipose tissue between skin and trachea. These people need a more thorough approach to the airway and a better solution to stoma hygiene in what is anticipated as life-long airway and apnea management.