CHAPTER 32 TRACHEAL, LARYNGEAL, AND OROPHARYNGEAL INJURIES

Structural mobility and elasticity are characteristics of the upper airway that make injury to these structures infrequent. Skeletal protection is also provided anteriorly by the mandible and sternum and posteriorly by the bony spinal column1 (Figure 1). Upper airway injuries are identified in only 0.03% of patients admitted to major trauma centers. These injuries are frequently lethal, which explains their higher reported occurrence in autopsy series.2,3 Penetrating mechanisms of injury are more common than blunt mechanisms of injury,1,2,4 the true incidence of which is unknown.1,5 Twenty-one percent of patients with upper airway injuries die within the first 2 hours after hospitalization.6 The diagnosis is often delayed in patients without immediate life-threatening upper airway trauma.6,7 Such delays often result in serious late complications.8,9 Limited experience in nonoperative and operative management of airway injuries has led to a wide variety of recommendations that may be considered under various clinical scenarios. For unstable, immediate life-threatening upper airway injuries, rapid airway control by any available means is essential for patient survival. Most authors agree that tracheal intubation through an open wound that communicates with the tracheobronchial tree is appropriate.1 Stable patients may benefit from bronchoscopic-guided tracheal intubation distal to the injury site, and blind endotracheal tube placement is almost always a poor choice for airway control.10 Airway injuries are always challenging to even the most experienced surgeon since traditional approaches to airway control are often contraindicated.

ANATOMY OF UPPER AIRWAY

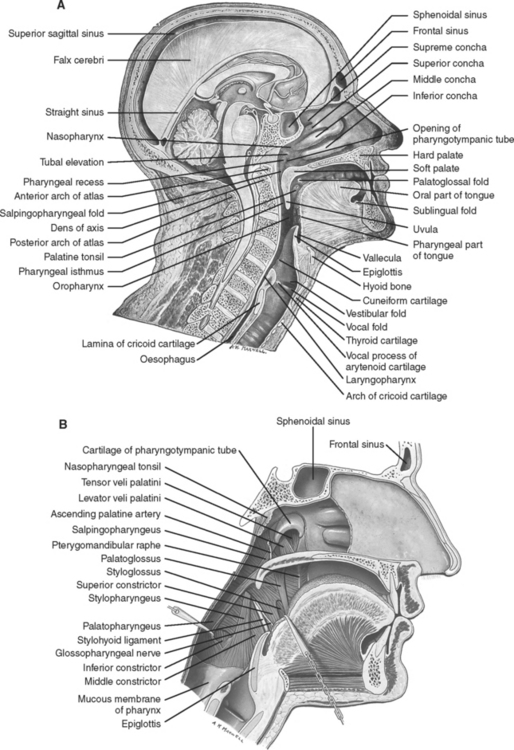

Pharynx

Surgical Anatomy

The pharynx consists of the following elements:

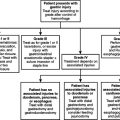

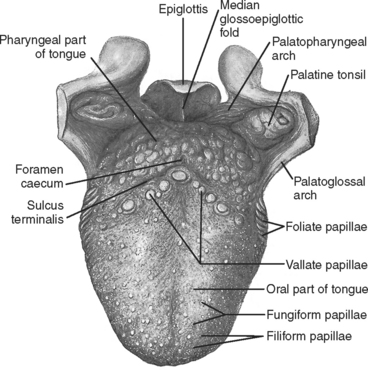

Figure 2 Contents of the oropharynx.

(From Gray’s Anatomy, 39th ed. St. Louis, Churchill Livingstone/Mosby, 2004, figure 33.4, with permission.)

PHARYNGEAL INJURY

Incidence

Isolated blunt pharyngeal injury is exceedingly rare. It is more often associated with concomitant cervical facial trauma. Penetrating pharyngeal injury occurs more commonly in the pediatric population from lacerations caused by intraoral foreign bodies.11

Mechanism of Injury

Pharyngeal trauma may occur from foreign body ingestion, blunt or penetrating trauma, or following laryngoscopy or other endoscopic procedures.12–15

Diagnosis

The initial clinical scenario varies. Patients with nonlethal injuries commonly present with dysphagia and odynophagia. Patients with more severe injuries may present with aphonia, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and severe acute respiratory failure that may rapidly lead to asphyxia if not treated.16 Injuries to the esophagus and pharynx are difficult to diagnose and may be missed during the management of other immediate life-threatening injuries. Oral bleeding, drooling, and subcutaneous emphysema all suggest upper digestive tract or airway injury.16 When possible, careful examination of the oropharynx and hypopharynx should be performed at the bedside.

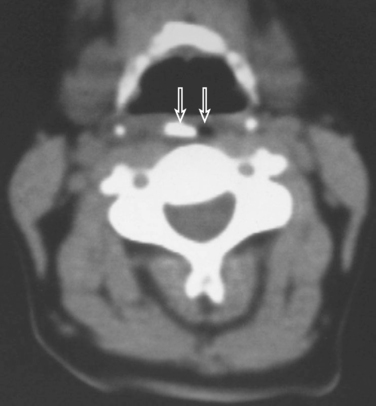

Lateral views of the neck and cervical CT scan may identify soft tissue air (Figures 5 and 6). A nonionic contrast-enhanced esophagram and/or esophagoscopy are indicated if injury is clinically suspected.17 Contrast leak may be revealed on esophagram (see Figure 5).

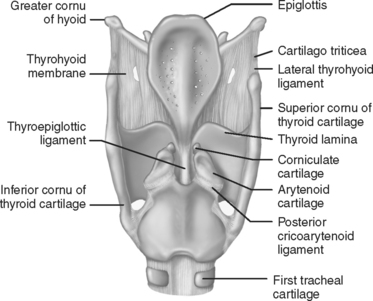

LARYNX

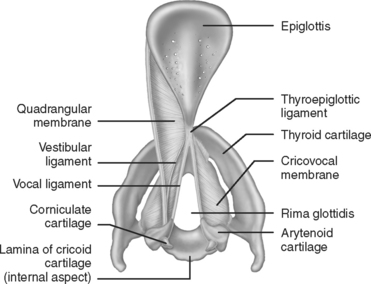

Surgical Anatomy

The larynx is composed of the following elements:

Laryngeal Injury

Incidence

Laryngeal and cervical tracheal injuries account for less than 1% of trauma cases seen in most major trauma centers.2,17 These injuries are rare compared to the total number of injuries that occur to the head and neck area. Experience in managing laryngeal trauma is limited because of these small numbers. External laryngeal trauma occurs in 1/30,000 emergency room visits.18,19 The rare nature of laryngeal injuries is a consequence of multiple factors, including protection by the mandible and sternum, delayed or missed diagnoses of minor laryngeal injuries in major multitrauma victims, and patient mortality at the scene from airway loss and asphyxiation.20

Although rare, initial management of laryngeal injuries affects the immediate probability of patient survival and long-term quality of life. The larynx is a well-protected structure that is both anatomically and functionally complex. Blunt and penetrating laryngeal injuries may cause chronic problems with aspiration, phonation, and respiration.20

Mechanism of Injury

The mechanisms of laryngeal injury can be divided into blunt trauma (including crushing, clothesline, and strangulation injuries) and penetrating trauma. The degree and location of blunt laryngotracheal trauma are multifactorial. Sheely et al.21 found that 88% of injuries occurred above the fourth tracheal ring. Penetrating injury can occur at any level of the cervical trachea.

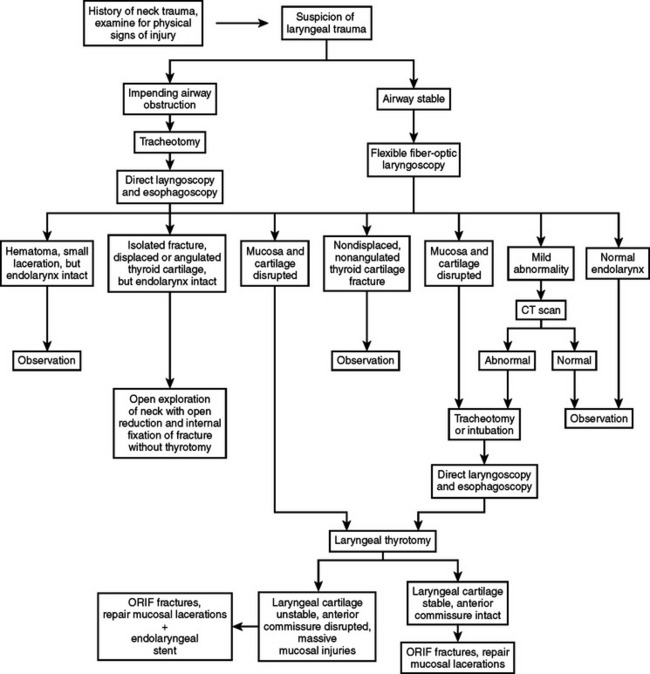

Diagnosis

Adherence to the essential principles of initial assessment delineated in the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS)® Manual is recommended. The ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation), concomitant resuscitation of the trauma victim, and a thorough secondary survey are essential for optimal management of airway injuries.22 Early recognition of these injuries requires a high index of suspicion based on mechanism of injury and findings identified during cervical and chest examination. Clinical signs and symptoms may include stridor, acute respiratory distress, cervical tenderness, subcutaneous emphysema, and cervical hematoma when associated with major vascular injury.23 Hemoptysis suggests that an intralaryngeal laceration may be present.23 This is more common with penetrating injury, but also occurs from blunt laryngeal trauma with an associated laryngeal cartilage fracture.23 Diagnostic procedures such as direct laryngoscopy, fiber-optic bronchoscopy, and cervical helical, contrast-enhanced multidetector (16 slices minimum) computed tomography (CT) with angiography are all beneficial if the patient’s clinical condition permits performing these tests.17,24 A sample algorithm for the evaluation of patients with laryngeal injuries is described (Figure 8).

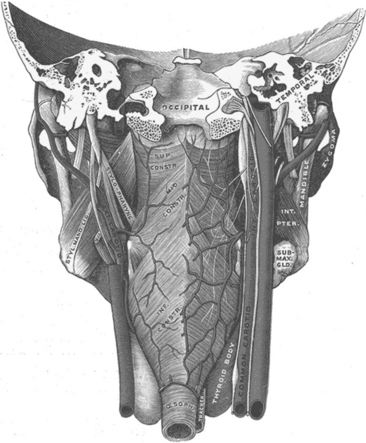

TRACHEA

Surgical Anatomy

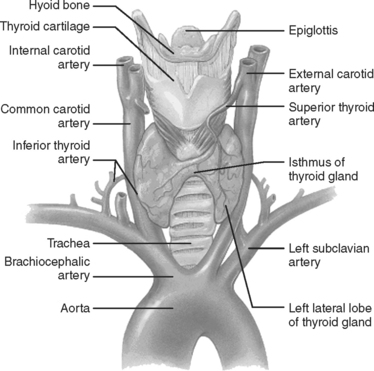

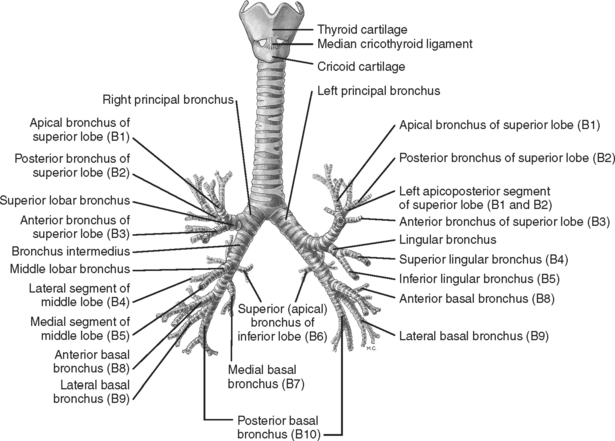

The trachea is a cartilaginous and membranous tube. It extends from the lower part of the larynx, at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra, to the upper border of the fifth thoracic vertebra. There it divides into the two main stem bronchi. The trachea is an ellipsoid cylinder that is flattened posteriorly. The average adult trachea measures about 11 cm in length with a diameter that varies from 2 to 2.5 cm. The pediatric trachea is smaller, more deeply placed, and more mobile. Half of the trachea lies within the neck and half is intrathoracic. The anterior two thirds of the trachea are composed of 18 to 22 “U”-shaped cartilages. The membranous posterior wall of the trachea is in apposition with the anterior wall of the esophagus. The bifurcation of the mainstem bronchi forms the carina at approximately the fourth to fifth thoracic vertebrae. The trachea is supplied with blood by the inferior thyroid arteries. Similarly named veins form the thyroid venous plexus. Tracheal innervation is derived from the vagus nerves, the recurrent laryngeal nerves, and from the sympathetic chain. The recurrent laryngeal nerve lies within the tracheoesophageal groove formed by the close proximity of the lateral aspects of the trachea and the esophagus (Figures 9, 10, and 11).

Figure 9 Anatomy of the larynx, cervical, and upper thoracic trachea.

(Copyright 2001 Benjamin Cummings, an imprint of Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.)

Figure 10 The cartilages of the larynx, trachea, and bronchi: anterior aspect.

(From Gray’s Anatomy, 39th ed. St. Louis, Churchill Livingstone/Mosby, 2004, figure 63.12, with permission.)

Tracheal Injury

Incidence

Disruption of the tracheobronchial tree is a rare occurrence and most surgeons’ experience is limited. On average, one such case is seen per year in large trauma centers.25 Bertelsen and Howitz4 reviewed 1178 postmortem reports of trauma deaths and found 33 (2.8%) with tracheal and/or bronchial disruptions. Of these 33 cases, 27 were dead at the scene.4

Complete cervical transection is rarer still. The true incidence (and tracheobronchial injuries in general) is unknown.26,27 There have been a number of case reports and small series described in the literature; however, the extant surgical experience remains limited.26

Knowledge of emergency airway management is essential. Loss of the airway in this clinical circumstance can rapidly lead to serious complications and/or the patient’s demise.17,28

Mortality in those patients who do not have complete airway loss at the time of injury is due to the severity of associated injuries. Those patients who arrive alive to a trauma center with isolated tracheobronchial injuries, including complete transection, have a reasonable chance for survival if the trauma surgeon has mastered the skills required for managing a difficult airway.29

Beskin30 reported the first successful repair of a complete cervical transection after blunt trauma in 1957. Hood and Sloan31 in 1959 collected 18 cases of tracheobronchial injury in the world literature. Complete tracheal transection was “rarely found.” In a more recent series, Eckert et al.3 reported a total of 105 tracheobronchial injuries, of which 75 were from penetrating trauma and 30 from blunt trauma. Of these, only 24 patients survived the transfer from the scene of the accident to the trauma center. Of the 30 blunt trauma victims reported in this series, 18 were dead on arrival at the emergency department. The majority of those who arrived alive, regardless of the mechanism of injury, had no other associated injuries (15 of 24 [63%]), and the remainder had only one other associated injury, including esophageal injuries (9 of 24 [37%]).3 In the same series, the most commonly injured segment of the tracheobronchial tree in survivors was the cervical trachea (37%). The total number of complete tracheal transections in Ecker and associates’ series is unknown.

Kelly et al.6 reviewed 106 patients with tracheobronchial injuries of which only 6 had a blunt mechanism of injury.6 They concluded that a surgeon must adopt a rapid, aggressive surgical approach to these patients in order to prevent lethal outcomes.6

Mechanism of Injury

Cervical trachea

Injuries to the cervical trachea may be caused by blunt or penetrating trauma. Penetrating injury is relatively straightforward. With the exception of shrapnel wounds, this consists of a traumatic defect created by the trajectory of the knife or bullet. Knife wounds more commonly occur in the cervical trachea, while gunshot wound injuries may occur at any point along the course of the tracheobronchial tree.17–27

In one review, blunt injury to the cervical tracheal was reported to occur in less than 1% of all 1248 blunt trauma patients admitted over the study period. In this anatomic region, blunt injuries to the larynx are the most frequent.17 They usually result from motor vehicle accidents or sports injuries, and direct blows to this area (e.g., “clothesline injury”).17–27

Intrathoracic tracheal injury

Injuries in this region are more commonly caused by blunt trauma, but may also result from penetrating injuries. In the former, the exact mechanism is unknown. Several theories have been advanced. This injury is often associated with sudden and forceful compression of the thorax. It is postulated that a rapid anteroposterior compression of the trachea in combination with a closed glottis causes markedly increased tracheal intraluminal pressure. When shearing forces are added to the tracheobronchial tree between the relatively stationary cricoid cartilage and carina (encountered during rapid deceleration), bronchial rupture may occur. Intrathoracic tracheal disruption usually occurs at the junction of the membranous and cartilaginous trachea within 2 cm of the carina. Vertical lesions are rare. When they do occur, they are more commonly located posteriorly where the cartilage is less evident. Bronchial injuries more commonly involve the main bronchi. They tend to occur within 2.5 cm of the carina.7–9,27

Gunshot wounds are the most frequent penetrating injuries. The incidence of thoracic tracheobronchial injury increases with transmediastinal gunshot wounds. Injuries to the heart, great vessels, and esophagus are common in these cases, and are major contributors to morbidity and mortality.27

Diagnosis

A thorough physical examination and knowledge of the mechanism of injury are the first and most important steps in diagnosing a tracheobronchial injury. Clinical findings suggesting airway injury vary according to the mechanism of injury. Cicala et al.32 reviewed nine patients following stab wounds. A laceration directly communicating with the airway was present in five cases. Subcutaneous emphysema was apparent on physical examination and on lateral cervical spine radiograph in three cases. Only one patient had no obvious clinical or radiographic findings to suggest an airway injury. This patient had a small puncture laceration of the cricotracheal membrane which was diagnosed by bronchoscopy. The majority of patients presenting with gunshot wounds to the trachea will show physical or radiographic finding that suggest airway injury on a plain radiograph of the neck or chest.32 In the study by Cicala and colleagues,32 two patients with gunshot wounds to the cervicothoracic trachea developed tension pneumothorax with massive air leak during resuscitation. Two others had fractures of the thyroid cartilage without any airway compromise. One was diagnosed by direct palpation on physical examination. The other patient was diagnosed by cervical CT scan. Hemoptysis, in addition to other findings, was noted in two of the gunshot wound victims.32

Blunt trauma patients who survive to the emergency department may present with a wide spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms dependant on the severity and location of the injury to the cervical thoracic trachea. Blunt cervical tracheal injury may create severe respiratory compromise leading to rapid acute respiratory failure and asphyxia. Alternatively, patients with less severe injuries may present with stridor, hoarseness, hemoptysis, and subcutaneous emphysema.24,32

Plain radiographs of the neck and chest may be diagnostic. Subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and chest wall on plain radiographs or CT scan should prompt further evaluation if clinical suspicion favors a major airway injury.1–6,10–12,32 Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is the first step in confirming a tracheal injury.27,33 Indications for bronchoscopy include a large pneumomediastinum, persistent pneumothorax, or a large, persistent air leak after placement of a functional thoracostomy tube; persistent atelectasis; and expanding severe subcutaneous emphysema.34 Bronchoscopy is the most accurate and reliable means to establish the diagnosis, determine the site and define the extent of the injury.35 Debate remains as to whether rigid or flexible bronchoscopy is superior in this setting. Disadvantages of rigid bronchoscopy include the need for a general anesthetic and a stable cervical spine. Flexible bronchoscopy does not require a general anesthetic, and may be used in patients whose cervical spine may be injured. Fiber-optic bronchoscopy is not only diagnostic, but may also be useful in establishing an airway with bronchoscopically guided endotracheal tube placement.36

Preoperative assessment of the vocal cords in this setting is strongly recommended. Direct laryngoscopy may be necessary to evaluate the function of the vocal cords. The presence of a recurrent laryngeal nerve injury causing vocal cord paralysis may assist the operating surgeon in determining whether tracheostomy is needed regardless of the location or extent of airway injury.37,38

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

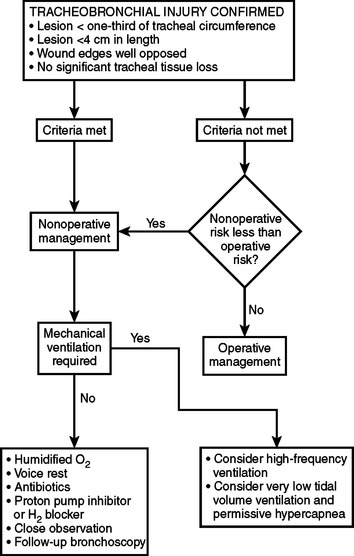

Nonoperative Management

Gomez-Caro et al.39 recently reported the successful management of 17 patients with iatrogenic tracheobronchial injuries between 1993 and 2003. Many of these lesions were as large as 4 cm in length. The authors reported no complications or deaths directly caused by nonoperative management. Clinical and endoscopic follow-up in 14 of 17 patients was uneventful. Guidelines for nonoperative management include vital signs stability, no associated esophageal injury, no issues with mechanical ventilation or intubation (if necessary), no development of severe subcutaneous emphysema or mediastinal emphysema, and no signs of sepsis.39 Additional requirements for nonoperative management have been published.27 These include only small tracheobronchial lacerations, such as those with less than one-third of the circumference of the trachea, well-opposed edges, no significant tissue loss, no associated injuries, and no need for positive pressure ventilation. Intubation as well as tracheostomy should ideally be avoided. When necessary, endotracheal intubation with placement of the endotracheal tube balloon distal to the tear has been proposed by Marquette et al.40 This technique has been successfully used on three occasions by one of the authors (SN). Nonoperative management includes administering prophylactic antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors, very close observation, and close bronchoscopic follow-up.27 A sample algorithm is provided in Figure 12.

Operative Management

Patients diagnosed with a major tracheobronchial injury should always undergo surgery unless medical instability or severe associated injuries are significantly prohibitive.41,42 In those situations, all efforts are made to support and stabilize the patient while maintaining adequate oxygenation and ventilation. High-frequency ventilation may be helpful. Permissive hypercapnia using very low tidal volumes (less than 5 ml/kg) has also been successfully used.43

The majority of patients are optimally managed with early surgery. The site of injury dictates the operative approach. These injuries are often challenging to even the most experienced surgeon, and appropriate consultation with an otolaryngologist for high cervical injuries or a thoracic surgeon for more distal intrathoracic injuries may be helpful.

Prior consultation with the anesthesiologist is crucial. A variety of endotracheal tubes, connectors, and ventilator tubing should be available on the operative table prior to opening the chest. Intubation over a bronchoscope in the operating room is best for optimal tube placement. Double-lumen tubes are beneficial for providing single-lung ventilation. However, their larger size may cause further damage and hinder the operative repair. Positioning the patient for thoracotomy and opening the chest may cause rapid deterioration from hypoxemia and hypoventilation. Opening the chest quickly with direct intubation of a major bronchus through the operative field may be necessary. The surgeon may also be able to direct the orotracheal tube from the upper trachea into the uninjured bronchus to provide one lung ventilation. If the anatomy of the injury is not completely known, two ventilators should be available in the operating room so that bilateral single lung ventilation can be provided if needed. The Univent® endobronchial blocker may also be helpful if there is active bleeding from one of the mainstem or segmental bronchi. This device incorporates an endotracheal tube with a maneuverable device that can be directed into and occlude a mainstem bronchus, an intermediate trunk, or a lobar bronchus.44

Repair of the trachea and bronchi requires optimal debridement of all devitalized tissue and primary end-to-end anastomosis. Either permanent or absorbable monofilament sutures are preferred. The authors prefer a running monofilament absorbable suture. All knots are tied external to the lumen to reduce the risk of granuloma formation. Management “pearls” are provided in Table 1.

Source: Mathisen DJ, Grillo H: Laryngotracheal trauma. Ann Thorac Surg 43(3):254–262, 1987.

MORBIDITY

Early Complications

In the early postinjury period following tracheal or laryngeal injury, loss of airway represents the greatest immediate threat. The need for definitive airway control is dictated by clinical signs of respiratory insufficiency such as dyspnea, tachypnea, hypoxemia, or massive hemoptysis. When laryngeal injury is suspected, care should be taken when passing the tube through the area of injury as partial tears can be converted into complete tears. Tension pneumothorax and massive subcutaneous emphysema may lead to mechanical ventilatory failure from mechanical constraints limiting pulmonary expansion. Endotracheal intubation can be attempted with extreme caution. When advancing the tube past the vocal cords care should be taken if tracheal injury is present or suspected. Nasotracheal intubation with a no. 7 or smaller cuffed endotracheal tube over a flexible bronchoscope has been proposed as one option in the stable patient.12,45 This should ideally be performed in the operating room or wherever conditions for performing an immediate surgical airway are optimal. Identification of the injury and strategically guided tube placement may be possible while minimizing iatrogenic trauma during intubation. This technique may be particularly useful in cases of nearcomplete or complete tracheal transection when suspected preoperatively to advance the tube into the distal tracheal segment.45 This maneuver must be performed by an experienced bronchoscopist. Even in cases when complete tracheal transection has occurred, adequate ventilation and oxygenation may be achieved with intubation of only the proximal tracheal remnant provided that the paratracheal tissues of the neck and superior mediastinum are still intact. Caution should be taken in this setting at the time of operation or attempted surgical airway control when entering this space from a cervical incision; rapid ventilatory failure and cardiopulmonary collapse can occur when this air space is entered and this distal tracheal segment has not been secured with an airway.26,46 The distal tracheal segment may retract back into the superior mediastinum and be difficult to access from a cervical incision. This may be prevented by performing a sternotomy prior to entering the pretracheal space when complete tracheal transection is suspected preoperatively.26

Tension pneumothorax can lead to rapid cardiopulmonary collapse if not quickly recognized and treated. While temporary improvement may be achieved, needle thoracostomy should be reserved for patients with impending cardiopulmonary collapse in the prehospital or emergency department setting. Immediate placement of one or more tube thoracostomies is the ideal treatment and may be life-saving. Patients with tracheobronchial injuries may develop a large air leak following pleural space drainage. In addition to increasing the negative pressure suction applied to the pleural space, advanced ventilatory strategies may be required to improve gas exchange. Low tidal volume ventilation, high-frequency jet ventilation, and highfrequency oscillatory ventilation have all been used with success to reduce peak airway pressure, increase mean airway pressure, reduce air leak, and promote healing at the site of injury.43,47,48

Pneumomediastinum may occur following tracheobronchial injury. Although hemodynamic compromise has been reported from air under pressure in the mediastinum, this appears to be unusual.35,49 Treatment is directed toward the underlying injury and resolution following injury repair, and recovery is the rule.

Subcutaneous emphysema can be massive, spreading to all areas of the body very quickly. Although treatment with multiple incisions or drains has been advocated,50,51 the emphysema itself has no direct adverse sequelae and is usually self-limiting.

Associated injuries are common and account for a substantial portion of early morbidity. A high index of suspicion for these injuries is maintained throughout early evaluation. Patient management based on ATLS® guidelines will minimize associated morbidity.52

Late Complications

The incidence of tracheobronchial stenosis following injury is 3.8%–9.3% following surgical repair.41,53 Stenosis may also occur when nonoperative management of a tracheal or bronchial tear is attempted.43 Initial measures to reduce inflammation include corticosteroid therapy and proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers to reduce aspiration of acidic gastric contents. Steroid therapy is controversial. The risks of immunosuppression and compromised wound healing must be compared to the benefits of reduced scarring and stenosis.54,55 Steroids may be beneficial during nonoperative management to reduce stenosis from hypertrophic granulation tissue, but there are currently no large studies to refute or support this therapy. Factors associated with a higher incidence of tracheal stenosis include degree of tracheal injury and increased time to operative repair.56 Others have not found increased stenosis rates when operative repair is delayed.41,57 Timing of operative repair is determined by associated injuries and overall physiologic status. Surgical repair should proceed as soon as possible to reduce this potential complication. Good surgical technique can reduce postoperative tracheal stenosis. Complete debridement of devitalized tissue, wide mobilization to reduce anastomotic tension and possibly the use of absorbable sutures are principles that may reduce inflammation and enhance normal healing repair site. Vascularized pedicles of muscle, usually the sternocleidomastoid or the strap muscles, sewn as a buttress to the anastomotic site have been shown to reduce the rate of anastomotic dehiscence, leak, and subsequent fistula formation.41 Tracheal stenosis is suspected when stridor, dyspnea, or air hunger develop following tracheal repair or injury.54 Usually the history is one of worsening progression over several days to weeks. Voice changes may occur simultaneously. Other symptoms may include postobstructive atelectasis or pulmonary sepsis, particularly following bronchial or distal segment repairs.57

Flexible or rigid bronchoscopy provides an accurate diagnosis and an opportunity for simultaneous treatment. Modern multidetector CT scanners are also highly sensitive and specific for diagnosing tracheobronchial pathology.58,59 Anatomic detail with three-dimensional reconstruction is very useful in planning operative or interventional repair. Treatment options include (1) endoscopic dilatation with steroid therapy60; (2) silicone, metal, or Teflon stent placement61,62; (3) Nd-Yag laser ablation of scar tissue63; or (4) open surgical repair. All of these treatments have been individually successful, and the therapeutic approach in any given patient must be individualized based on the extent of stenosis, severity of comorbid conditions and the experience and resources of each surgeon and facility. Many different open surgical techniques have been described but general principles should include resection and debridement of tracheal scar with tracheal mobilization and primary end-to-end anastomosis with absorbable suture.

Tracheoesophageal fistula may occur following a delay in diagnosis and/or treatment of esophageal and/or tracheal injuries. A high index of suspicion for esophageal or tracheal injury must be maintained whenever the other is identified, and thorough evaluation with bronchoscopy, esophagoscopy, or esophagography is usually required. Careful and thorough intraoperative evaluation at surgery is mandatory. Full mobilization of the cervical esophagus and intraluminal instillation of methylene blue have been advocated to avoid missing a subtle esophageal tear. Following identification of a late tracheoesophageal fistula, delayed repair is planned following medical stabilization, treatment of aspiration pneumonitis or pneumonia, and gastrostomy tube placement. Repair consists of wide esophageal and tracheal mobilization, debridement to healthy tissue, and primary end-to-end anastomosis. Transposition of a vascularized pedicle of muscle between the areas of repair to be dictated by the anatomic location of the fistula is mandatory to reduce anastomotic dehiscence and recurrent fistula formation.41

Voice changes such as dysphonia and laryngeal stenosis can occur following laryngeal injury when architectural relationships within the voice box are altered by healing. Poor outcomes are associated with injuries that create significant mucosal disruption, arytenoid dislocation, or exposed cartilage. One series reported an association between delays in operative repair beyond 24 hours and increased rates of airway stenosis ranging from 13%–31%.64 Laryngeal stenting, particularly when one or both vocal cords are mobile, helps preserve the voice by normalizing the shape of the anterior commissure. Stents should be removed as soon as possible (usually 10–14 days) because of the risk of compromised mucosal perfusion with prolonged usage.65

Vocal cord paralysis from recurrent laryngeal nerve injury may be unilateral or bilateral following tracheal or laryngeal injuries. Cricotracheal separation carries a 60% risk of recurrent nerve injury, which is often bilateral.55 Resolution of neurapraxia and nerve regeneration may occur up to 1 year following injury, resulting in resolution of vocal cord paralysis in some cases.

Laryngeal webs, granulomas, and hypertrophic granulation can develop several months following laryngeal trauma. Follow-up endoscopy with laser ablation can prevent chronic problems from these less serious complications.64

Other Potentially Life-Threatening Complications

Pharyngeal injuries can lead to serious complications particularly when the diagnosis is delayed. Retropharyngeal abscess is uncommon but potentially life threatening if upper airway obstruction or mediastinitis develops.66 A short course of prophylactic antibiotics may reduce the risk of this complication. The diagnosis is usually apparent upon inspection of the oropharynx and palatine tonsils. Retropharyngeal air may be present on lateral cervical radiograph. If present, further evaluation should include cervical and mediastinal CT scan. Surgical drainage of the abscess and broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics are indicated. Surgical intensive care unit admission and possible intubation may be necessary in severe cases.67

Injury to the internal carotid artery should also be considered whenever an impalement injury of the posterior pharynx is diagnosed. Asymptomatic dissection of the internal carotid artery followed by arterial occlusion or embolization to the cerebral vasculature may develop over several hours to days resulting in severe neurologic deficits. Therefore, a high index of suspicion and screening with angiography should be performed when clinical presentation suggests this possibility.67 CT angiography (CTA) has improved in recent years with the multidetector scanners. Experience suggests that CTA may be a good screening tool to identify these injuries.68–70 Anticoagulation to prevent propagation and occlusion of the dissection is standard therapy, but experience with carotid stents is growing. Carotid stenting may be an alternative in selected cases. Surgical repair of the internal carotid artery is usually impossible due to the distal location of most lesions.70

MORTALITY

The mortality rate for tracheobronchial injuries in most modern series is less than 30%.29,41,53,57 A large literature review pooled all patients with blunt tracheobronchial injury reported between 1873 and 1996 and found a 9% mortality rate since 1970 for patients who arrived alive at the hospital.57 Left-sided injuries, high-speed deceleration, and crush mechanisms are associated with the poorest outcomes. Autopsy series suggest that 80% of patients with tracheobronchial injuries die at the scene.57 Early mortality results from associated injuries and loss of airway.

Mortality from laryngeal injuries has been reported as high as 40% and is primarily attributable to asphyxiation from airway compromise. Penetrating laryngeal injuries appear to have a lower mortality (20%). Death from penetrating injuries is more attributable to associated injuries, particularly esophageal and major vascular injuries.55

Attributable mortality from pharyngeal injuries is difficult to determine since these injuries are rarely life threatening. Death is usually attributable to the internal carotid artery thrombosis, cervical infection, or mediastinitis. When present, the outcome for each of these complications is dependent on early diagnosis and treatment.67

1 Roger SC, Kenneth AK, Alan, et al. Initial evaluation and management of upper airway injuries in trauma patients. J Clin Anesth. 1991;3:91-98.

2 Gussack GS, Jurkovich GJ, Luterman A. Laryngotracheal trauma: a protocol approach to a rare injury. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:660-665.

3 Ecker RR, Libertini RV, Rea WJ, et al. Injuries of the trachea and bronchi. Ann Thorac Surg. 1971;11:289-298.

4 Bertelson S, Howitz P. Injuries of the trachea and bronchi. Thorax. 1972;27:188-194.

5 Nahum AM. Immediate care of acute blunt laryngeal trauma. J Trauma. 1969;9:112-125.

6 Kelly JP, Webb WR, Moulder PV, et al. Management of airway trauma. I: Tracheobronchial injuries. Ann Thorac Surg. 1985;40(6):551-555.

7 Mahaffey DE, Creech O, Boren HG, et al. Traumatic rupture of the left-main bronchus successfully repaired eleven years after injury. J Thorac Surg. 1956;32:312-331.

8 Kirsh MM, Orringer MB, Behrendt DM, et al. Management of tracheobronchial disruption secondary to nonpenetrating trauma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1976;22(1):93-101.

9 Grillo HC. Surgery of the trachea. In: Ravitch MM, editor. Current Problems in Surgery. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1970:3-59.

10 Trone TH, Schaefer SD, Carder HM. Blunt and penetrating laryngeal trauma: a 13-year review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1980;88(3):257-261.

11 Fitz-Hugh GS, Powell JB. Acute traumatic injuries of the oropharynx, laryngopharynx, and cervical trachea in children. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1970;3(2):375-393.

12 Demetriades D, Velmahos GG, Asensio JA. Cervical pharyngoesophageal and laryngotracheal injuries. World J Surg. 2001;25(8):1044-1048. (review)

13 Pereira WJr, Kovnat DM, Snider GL. A prospective cooperative study of complications following flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Chest. 1978;73(6):813-816.

14 Heater DW, Haskvitz L. Suspected pharyngoesophageal perforation after a difficult intubation: a case report. AANA J. 2005;73(3):185-187.

15 Carey WD. Indications, contraindications and complications of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. In: Sivak MVJr, editor. Gastroenterologic Endoscopy. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1987:296-306.

16 Goudy SL, Miller FB, Bumpous JM. Neck crepitance: evaluation and management of suspected upper aerodigestive tract injury. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(5):791-795.

17 Fuhrman G, Steig F, Buerk C. Blunt laryngeal trauma: classification and management protocol. J Trauma. 1990;30:87-92.

18 Jewett BS, Shockley WW, Rutledge R. External laryngeal trauma analysis of 392 patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(8):877-880.

19 Biller HF, Moscoso J, Sanders I. Laryngeal trauma. In: Ballenger JJ, Snow JB, editors. Otorhinolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 15th ed. Media, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1996:518-525.

20 Meislin HW, Iserson KH, Kabak KR, et al. Airway trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1983;1:295-312.

21 Sheely CH2nd, Mattox KL, Beall ACJr. Management of acute cervical tracheal trauma. Am J Surg. 1974;128(6):805-808.

22 American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support for Doctors: Instructor Course Manual. Chicago: American College of Surgeons, 1997.

23 Snow JBJr. Diagnosis and therapy for acute laryngeal and tracheal trauma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1984;17(1):101-106.

24 Schaefer S. Primary management of laryngeal trauma. Ann Otorlaryngol. 1982;91:399-402.

25 Major CP, Floresguerra CA, Messerschmidt WH, Lewis JV. Traumatic disruption of the cervical trachea. J Tenn Med Assoc. 1992;85(11):517-518.

26 Norwood SH, McAuley CE, Vallina VL, et al. Complete cervical tracheal transection from blunt trauma. J Trauma. 2001;51(3):568-571.

27 RD Riley, PR Miller & JW Meredith: Injury to the esophagus, trachea, and bronchus. In Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, editors: Trauma, 5th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, pp. 544–550

28 Lazar HL, Thomashow B, King TC. Complete transection of the intrathoracic trachea due to blunt trauma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1984;37(6):505-507.

29 Flynn AE, Thomas AN, Schecter WP. Acute tracheobronchial injury. J Trauma. 1989;29:1326.

30 Beskin CA. Rupture-separation of the cervical trachea following a closed chest injury. J Thorac Surg. 1957;34:392-394.

31 Hood RM, Sloan HE. Injuries to the trachea and major bronchi. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1959;38:458-480.

32 Cicala RS, Kudsk KA, Butts A, et al. Initial evaluation and management of upper airway injuries in trauma patients. J Clin Anesth. 1991;3:91-98.

33 Roberge RJ, Squyres NS, Demetropoulous S, et al. Tracheal transection following blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:47-52.

34 Spencer JA, Rogers CE, Westaby S. Clinico-radiological correlates in rupture of the major airways. Clin Radiol. 1991;43:371.

35 Hancock BJ, Wiseman NE. Tracheobronchial injuries in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:1316-1319.

36 Angood PB, Attia EL, Brown RA, Mulder DS. Extrinsic civilian trauma to the larynx and cervical trachea—important predictors of long-term morbidity. J Trauma. 1986;26:869.

37 Iwasaki M, Kaga K, Ogawa J, et al. Bronchoscopy findings and early treatment of patients with blunt tracheo-bronchial trauma. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;35:269.

38 Hara KS, Prakash UBS. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy in the evaluation of acute chest and upper airway trauma. Chest. 1989;96:627.

39 Gomez-Caro A, Diez FJM, Herrero PA, et al. Successful conservative management in iatrogenic tracheobronchial injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1872-1878.

40 Marquette CH, Bocquillon N, Roumilhac D, et al. Conservative treatment of tracheal rupture. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:399-401.

41 Richardson JD. Outcome of tracheobronchial injuries: a long-term perspective. J Trauma. 2004;56:30-36.

42 Thompson EC, Porter JM, Fernandez LG. Penetrating neck trauma: an overview of management. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60(8):918-923.

43 Self ML, Mangram A, Berne JD, et al. Nonoperative management of severe tracheobronchial injuries with positive end-expiratory pressure and low tidal volume ventilation. J Trauma. 2005;59:1072-1075.

44 Nishiumi N, Maitani F, Yamada S, et al. Chest radiography assessment of tracheobronchial disruption associated with blunt chest trauma. J Trauma. 2002;53:372-377.

45 Schoem SR, Choi SS, Zalzal GH. Pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax from blunt cervical trauma in children. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:351-356.

46 Bowley D, Plani F, Murillo D, et al. Intubated, ventilating patients with complete tracheal transection: a diagnostic challenge. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:245-247.

47 Naghibi K, Hashemi SL, Sajedi P. Anaesthetic management of tracheo-bronchial rupture following blunt chest trauma. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47(7):901-903.

48 Clark RH, Wiswell TE, Null DM. Tracheal and bronchial injury in high-frequency oscillatory ventilation compared with conventional positive pressure ventilation. J Pediatr. 1987;111(1):114-118.

49 Liistro G, Goncette L, Rodenstein DO. Tracheal laceration and tension pneumomediastinum of spontaneous favorable outcome. Acta Clin Belg. 1998;53:44-46.

50 Sherif HS, Ott DA. The use of subcutaneous drains to manage subcutaneous emphysema. Tex Heart Inst J. 1999;26:129-131.

51 Herlan DB, Landreneau RJ, Ferson PF. Massive spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema: acute management with infraclavicular “blow holes.”. Chest. 1992;102:503-505.

52 American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Advanced Trauma Life Support for Doctors, 7th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons, 2004.

53 Balci AE, Erin N, Erin S, et al. Surgical treatment of post-traumatic tra-cheobronchial injuries: 14-year experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:984-989.

54 Healy GB. Subglottic stenosis: pediatric otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1989;22(3):599-605.

55 Atkins BZ, Abbate S, Fisher SR, et al. Current management of laryngotracheal trauma: case report and literature review. J Trauma. 2004;56:185-190.

56 Reece GP, Shatney CH. Blunt injuries of the cervical trachea: review of 51 patients. South Med J. 1988;81(12):1542-1548.

57 Kiser AC, O’Brien SM, Detterbeck FC. Blunt tracheobronchial injuries: treatment and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:2059-2065.

58 Lim KE, Liu YC, Hsu YY. Tracheal injury diagnosed with three dimensional imaging using multidetector row computed tomography. Chang Gung Med J. 2004;27:217-221.

59 Moriwaki Y, Sugiyama M, Matsuda G, et al. Usefulness of the 3-dimensionally reconstructed computed tomography imaging for diagnosis of the site of tracheal injury (3D-tracheography). World J Surg. 2005;29:102-105.

60 Clement P, Hans S, de Mones E, et al. Dilation for assisted ventilation-induced laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1595-1598.

61 Huang C. Use of the silicone t-tube to treat tracheal stenosis of tracheal injury. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;7:192-196.

62 Mandour M, Remacle M, Van de Heyning P, et al. Chronic subglottic and tracheal stenosis: endoscopic management vs. surgical reconstruction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260:374-380.

63 Dowd NP, Clarkson K, Walsh MA, et al. Delayed bronchial stenosis after blunt chest trauma. Anesth Analg. 1996;82:1078-1081.

64 Thal ER, Nwariaku FE. Neck injuries. In: Maull MI, Rodriguez A, Wiles CEIII, editors. Complications in Trauma and Critical Care. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1996:270-272.

65 Leopold DA. Laryngeal trauma. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:106-112.

66 Luqman Z, Khan MAM, Nazir Z. Penetrating pharyngeal injuries in children: trivial trauma leading to devastating complications. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:432-435.

67 Schoem SR, Choi SS, Zalzal GH, et al. Management of oropharyngeal trauma in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:1267-1270.

68 Brietzke SE, Jones DT. Pediatric oropharyngeal trauma: what is the role of CT scan? Int J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:669-679.

69 Berne JD, Norwood SH, McAuley CE, Villareal DH. Helical CT angiography: an excellent screening test for blunt cerebrovascular injuries. J Trauma. 2004;57:11-19.

70 Berne JD, Reuland KS, Norwood SH, et al. Sixteen-slice multi-detector computed tomographic angiography improves the accuracy of screening for blunt cerebrovascular injury. J Trauma. 2006;60:1204-1209.