Toxoplasmosis

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• Describe the etiology and epidemiology of toxoplasmosis.

• Explain the signs and symptoms of acquired and congenital toxoplasmosis infection.

• Discuss the immunologic manifestations and diagnostic evaluation of toxoplasmosis, including the quantitative determination of IgM antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii.

• Analyze a case study related to toxoplasmosis.

• Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions.

• Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions.

• Describe the principle, interpretation, and limitations of the TORCH procedure.

Epidemiology

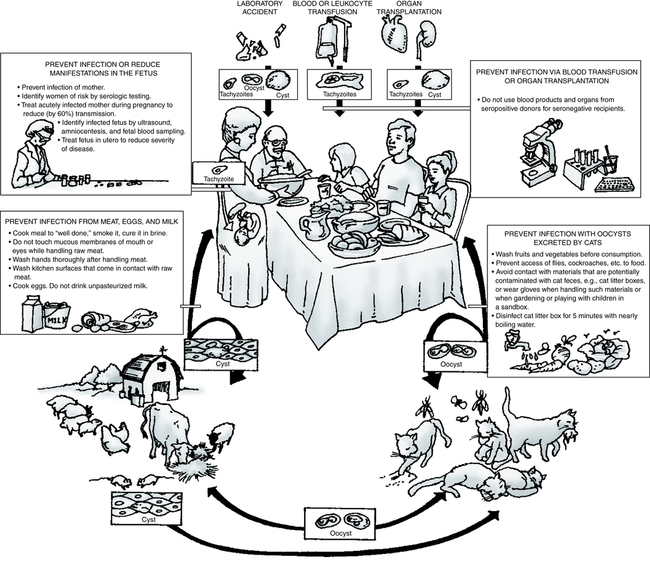

The definitive host is the house cat and other members of the Felidae family (Fig. 20-1). Domestic cats are a source of the disease because oocysts are often present in their feces. Accidental ingestion of oocysts by human beings and animals, including the cat, produces a proliferative infection in the body tissues. Fecal contamination of food or water, soiled hands, inadequately cooked or infected meat, and raw milk can be major sources of human infection. The risk for infection is higher in many developing and tropical countries, especially when people eat undercooked meat, drink untreated water, or are extensively exposed to soil.

Transplacental Transmission

It is recommended that all pregnant women be tested for toxoplasmosis immunity. If a patient is susceptible, screening should be repeated during pregnancy and at delivery. Prevention of infection in pregnant women should be practiced to avert congenital toxoplasmosis (Box 20-1). To further prevent infection of the fetus, women at risk should be identified by serologic testing and pregnant women with primary infection should receive drug therapy.

Signs and Symptoms

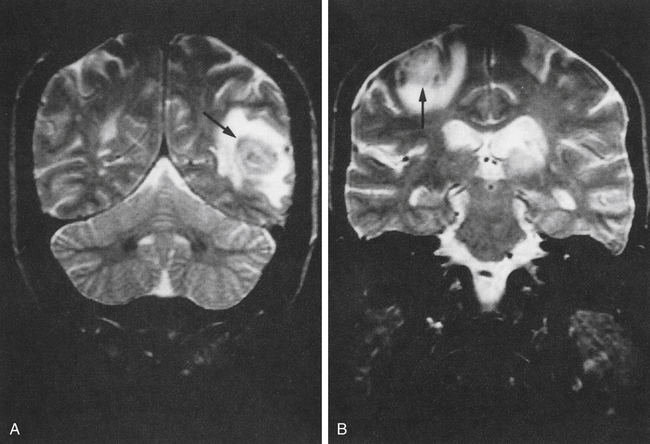

Toxoplasma can be harmful to individuals with suppressed immune systems. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS patients may result in death, even when treated (Fig. 20-2). Persons at risk can be identified by screening patients positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) for antibody to T. gondii.

Shown are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans of patients with AIDS. Arrows indicate areas infected with toxoplasmosis.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnosis of toxoplasmosis can be established by the following:

• Serologic tests (Table 20-1)

Table 20-1

Serologic Evaluation of Toxoplasmosis

| Test | Method | Recommended Use |

| T. gondii antibodies, IgG and IgM | Chemiluminescent immunoassay∗ | First-line test in endemic areas for identifying T. gondii infection in pregnant women; diagnosis of opportunistic infections in immunocompromised hosts |

| T. gondii by PCR | Confirmation of toxoplasmosis infection in immunocompromised hosts |

∗Note: The CDC suggests that equivocal or positive results be retested using a different assay from another reference laboratory specializing in toxoplasmosis testing (IgG Sabin dye test, IgM ELISA, reflex to avidity and/or other tests).

Adapted from Associated Regional and University Pathologists (ARUP): Reference test guide, 2012 (http://www. aruplab.com).

• Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Chapter Highlights

• Toxoplasmosis is a widespread disease in human beings and animals caused by Toxoplasma gondii, often found in cat feces.

• Fecal contamination of food or water, soiled hands, inadequately cooked or infected meat, and raw milk are sources of human infection. All mammals, including human beings, can transmit the infection transplacentally.

• In adults and children other than newborns, the disease is usually asymptomatic. A generalized infection probably occurs.

• Although spontaneous recovery follows acute febrile disease, the organism can multiply in any organ of the body or circulatory system.

• Congenital toxoplasmosis can result in CNS malformation or prenatal mortality.

• T. gondii is difficult to culture and diagnosis must be supported by serologic methods to determine levels of IgM and IgG antibodies to T. gondii. The presence of IgM antibodies to T. gondii in an adult indicates active infection. Detection of IgM also suggests active infection in the newborn.

• Serologic tests include IFA, chemiluminescent immunoassay, and PCR.