Toxin- and Drug-Induced Disorders of the Liver

Brigitte Le Bail

Charles Balabaud

Paulette Bioulac-Sage

Introduction

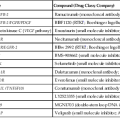

Because the liver is the major site of drug metabolism, it is also the major target of drug-induced injury. Despite rigorous preclinical and clinical toxicologic studies and safety analyses in clinical trials, the frequency of drug hepatotoxicity has remained relatively unchanged during the years, and drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is still the main reason for removal of a drug from the market. Furthermore, adverse chemical reactions are not confined to pharmaceutical drugs (i.e., the drug itself and its excipients used for classic therapeutic purposes): dietary supplements and herbal medicines, often used as self-medications, also represent potential hepatotoxins. Various environmental toxins and recreational drugs, such as alcohol, illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine, heroin, ecstasy), criminal poisons, and industrial toxins (e.g., natural toxins, mushrooms, industrial chemicals, pesticides), can also give rise to hepatotoxicity. The list of putative offending drugs and toxins is extremely long and evolves with time. Although all families of therapeutic agents can potentially be involved, a small group of drugs represent the most frequently incriminated molecules (Box 48.1). The circumstances of exposure to these various forms of liver toxins are listed in Box 48.2, with the exception of alcohol injury, which is discussed in Chapter 49.

Drug hepatotoxicity can be classified as either intrinsic or idiosyncratic. Intrinsic hepatotoxicity is predictable, dose dependent, and often characteristic of a particular agent when consumed in large quantities. Examples are ingestion of acetaminophen (paracetamol) and exposure to carbon tetrachloride or chloroform. Hepatotoxicity occurs in most of those who are exposed and starts shortly after some threshold for toxicity is reached. The mechanism of intrinsic injury can be direct, through damage to cells and organelles, or indirect, through conversion of a xenobiotic into an active toxin or through an immune-mediated mechanism. Idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity, by far the more frequent form of hepatotoxicity, involves unpredictable reactions that occur without warning and are unrelated to dose; they occur in particular hosts, depending on individual genetic variations in the metabolism of drugs and on environmental factors. Because the formation of reactive metabolites is a frequent mechanism of idiosyncratic reactions, the hepatotoxicity is highly dependent on the metabolic capacity of the host. In idiosyncratic toxicity, variable latency periods can be observed, from a few days to more than a year.

Diagnosis of a toxic liver injury or DILI is challenging, and it is often a diagnosis of exclusion and probability. Assessment of causality is difficult because almost all drugs and toxins are potentially hepatotoxic because of frequent idiosyncrasies and unpredictable toxicity, whereas predictable and dose-dependent liver toxins are rare. From a clinical or a pathologic point of view, any pattern of hepatic injury may be encountered and may mimic other liver diseases, and a single drug can induce different lesions in different patients. The clinical presentation is usually acute and largely reversible, but chronic disease can occur. The time of onset of liver dysfunction varies depending on the drug and the patient and can be long after the first ingestion of drug. Severe cases can occur and include mainly fulminant hepatitis: DILI is one of the major causes of acute liver failure with viral hepatitis. Significant fibrosis and cirrhosis may develop, and even hepatic tumors. In addition, hepatocytes are usually the target in DILI, but some drugs may target endothelial cells, cholangiocytes, hepatic stellate cells, and/or Kupffer cells.

The Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) has proposed consensus criteria for terminology in DILI, based on biologic tests, chronology, and availability of liver biopsy. Six categories of DILI can be defined in this system: hepatocellular injury, cholestatic injury, mixed injury, acute injury, chronic injury, and chronic liver disease (Table 48.1).

Table 48.1

CIOMS Consensus Criteria for Terminology in DILI

| Terminology | Criteria |

| Hepatocellular injury | Isolated increase in ALT >2 × normal, or ALT/ALP ≥5 |

| Cholestatic injury | Isolated increase in ALP >2 × normal, or ALT/ALP ≤2 |

| Mixed injury | ALT and ALP increased and 2 < ALT/ALP <5 |

| Acute injury | Above changes present for <3 mo |

| Chronic injury | Above changes present for >3 mo |

| Chronic liver disease | This term is used only after histologic confirmation |

ALP, Alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CIOMS, Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences; DILI, drug-induced liver injury.

The histologic examination of a liver biopsy specimen is not always performed, either because the toxic episode may quickly resolve or because the information provided is disappointing. Indeed, specific lesions are rare in this field. However, when analyzed by a specialist, the liver biopsy can often provide useful information for positive and differential diagnosis of DILI (Box 48.3). The lesions can be classified as to pattern of injury, a topic that is discussed in detail later in this chapter.

DILI should be included in the differential diagnosis in cases with any hepatic laboratory abnormalities or hepatic dysfunction, but the assessment of causality of a drug in liver disease is often difficult. Discussion between clinicians and pathologists is especially important in this field of hepatology.

Current preclinical tests for hepatotoxicity are inadequate, reflecting our limited understanding of the mechanisms of drug toxicity. In particular, “hypersensitivity” and “idiosyncratic” reactions remain poorly understood and probably affect individuals possessing a rare combination of genetic and nongenetic factors that lead to drug toxicity in a given environmental setting. Many meetings on this topic have been organized by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since 2001, and collection of data in regional or national registries (e.g., Spain, France, United States) or databanks has been encouraged. The goal of the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN; https://dilin.dcri.duke.edu/) is to collect clinical data, genomic DNA, and liver tissues from patients who have experienced idiosyncratic drug reactions, in an effort to determine pathogeny.1 Recent studies from these groups have focused on the specific group of DILI cases with features of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH),2 which could explain recurrent DILI with different drugs in a same patient.3

Despite much effort, hepatotoxicity remains a problem for many existing drugs, as well as those in development. This has a major economic impact because hepatotoxicity is the most frequent cause of postmarketing withdrawal of new medications.

This chapter reviews the main clinical features of toxin- and drug-induced disorders and describes the main pathologic patterns attributed to drugs and toxins. In the last part, some frequently prescribed hepatotoxic drugs are described more extensively to illustrate the variety of clinicopathologic presentations of liver injury.

For an extensive and detailed description of hepatotoxicity produced by a larger number of individual drugs, the reader is referred to a variety of specialized publications.4–21 Synthetic and actualized data can be obtained from specialized Web sites such as Hepatox, which was developed in France by Dr. Biour and is hosted on the Web site of the Association Française pour l’Etude du Foie (http://www.afef.asso.fr/liens/Hepatox/index.phtml), or from the Uppsala Monitoring Centre of the World Health Organization (WHO) database (http://who-umc.org).

Epidemiology

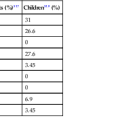

DILI accounts for approximately 10% of cases of acute hepatitis in adults and for more than 40% of cases in individuals older than 50 years.13 In various series, it has accounted for 10% to 20% of cases of fulminant and subfulminant hepatitis22 and for 2% to 5% of patients hospitalized for jaundice. The risk of a fulminant course is much greater for DILI (20%) than for viral acute hepatitis (1%). On the other hand, drugs are less often incriminated in chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis (<1% of cases).

However, it is probable that the real incidence of DILI is much higher because of unrecognized and benign presentations. In children, DILI is less frequent, but it is also an underrecognized cause of pediatric liver disease, and large series are rare. Children could represent 5% to 8.7% of DILI patients.23

A French study found an annual incidence of DILI of almost 14 cases per 100,000 population, a rate 16 times higher than that based on spontaneous reports.24 The most common causes of DILI are the analgesic drug acetaminophen and several antiinfectious agents such as antibiotics from different families (e.g., amoxicillin/clavulanic acid [AMC], erythromycin, minocycline), as well as antituberculosis drugs (especially isoniazid [INH]), psychotropic agents (e.g., chlorpromazine), anticonvulsants (e.g., valproic acid), anesthetics, oral contraceptives, lipid-lowering agents, antiinflammatory agents (e.g. diclofenac, disulfiram), and cardiovascular agents (e.g., amiodarone), as shown in large series16,25,26 (see Box 48.1). In children, apart from acetaminophen, antimicrobial and central nervous system agents are the most commonly implicated drug classes, representing 50% and 40% of cases, respectively, as demonstrated in the recent DILIN series.27 Another pediatric series from India emphasizes the role of antituberculosis drugs (e.g., INH, rifampicin [RFP], ethambutol) and anticonvulsants (phenytoin and carbamazepine),23 pointing out the geographic specificity for certain drug toxicities. In this Indian pediatric population, hypersensitivity features such as skin rashes, eosinophilia, fever, lymphadenopathy, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome were frequently seen (41%) and were associated with a better outcome.

The total number of drugs liable to be toxic to the liver exceeds 1100, and this long list must be frequently updated.28 The highest frequency of hepatotoxicity for marketed drugs has been approximately 1% (for tacrine), but for most drugs, the risk is low (1/10,000 to 1/100,000) or extremely low (1/100,000 to 1/1,000,000 for antihistaminic compounds or penicillin). However, evaluation of the accurate incidence and risk factors, as well as assessment of the causality of one or several toxic agents, remains a major problem in DILI.29

In addition, overdoses of certain drugs are well known to be extremely toxic, not only in the context of a therapeutic misadventure (or with repeated doses, particularly in cases of excessive alcohol ingestion) but as a method of suicide. In the latter instance, acetaminophen is the drug most frequently used for suicidal overdose among adolescents and young adult women in the United States and Great Britain. When given in therapeutic doses for a period of 14 days, acetaminophen produced significant asymptomatic elevations in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels among healthy volunteers, suggesting that subclinical injury may be more common than previously believed. There was also a much lower incidence of acetaminophen toxicity as a cause of acute liver failure in children compared with adults, with almost half of all cases being indeterminate in origin.30 Acetaminophen toxicity is reviewed more extensively later in this chapter.

The potential hepatotoxicity of herbal remedies commonly used for self-medication (i.e., alternative or “natural” treatments) and of other botanicals (e.g., the well-known mushroom poisoning from Amanita phalloides) should always be considered in the evaluation of pathology specimens. The list of confirmed or suspected hepatotoxic herbal components (e.g., Chinese herbs, germander31) is long, and the full extent of their toxicity remains unclear.32 Many alimentary supplements, including vitamins, minerals, and botanical extracts, are also recognized as possible cause of DILI, as reviewed by Navarro in 2009.21 For instance, many Herbalife products, used for nutrition or energy or to reduce stress, have been shown to commonly induce cytolysis, cholestasis, and even, in rare cases, acute liver failure.

Increased consumption of illicit drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and ecstasy, regardless of the route of administration (intranasally, intravenously, or by smoking), has increased the number of cases of hepatotoxicity33 and potentiated other factors of liver disease. For example, daily cannabis smoking is significantly associated with progression of fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.34

Frequently, hepatotoxicity is further potentiated by the use of other drugs in combination or by alcohol intake. Therefore, when prescribing a potentially hepatotoxic drug in a patient, it is particularly important to be aware of all additional risk factors for the liver in that patient, such as alcohol, diabetes, obesity, and chronic viral hepatitis. Otherwise, the risk of DILI will increase, and also the severity of the other liver diseases can worsen. During recent decades, for example, the evolving epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease caused by metabolic syndrome has potentiated the hepatotoxic properties of certain drugs such as methotrexate—and vice versa.35

Furthermore, a drug may be beneficial in the short term but harmful in the long term. For example, in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection who also have hepatitis B virus (HBV) or HCV coinfection, alcohol abuse, or other hepatic risk factors, prolonged therapy with didanosine may induce chronic liver disease and may cause severe liver complications, such as variceal bleeding and portal thrombosis.36

Clinical Assessment and Prediction of Hepatotoxicity

Side effects attributed to drugs and toxins in the liver are numerous and variable. Although a slight acute hepatocellular or cholestatic/mixed hepatitis is the most common presentation, DILI can mimic all forms of acute or chronic hepatitis as well as biliary or vascular hepatopathy. In addition, some liver tumors (e.g., hepatocellular adenoma, angiosarcoma) may be attributed to the long-term exposure to various drugs or toxins. Therefore, hepatologists and pathologists should consider possible drug-induced hepatotoxicity in the differential diagnosis of virtually any type of liver injury. Abnormal liver test results and nonspecific clinical signs may be present, including malaise, fatigue, abdominal discomfort, appetite loss, splenomegaly, icterus, or symptoms of acute liver failure. Signs of immunoallergic reaction, such as fever, rash, arthralgia, and eosinophilia, may be encountered but are infrequent and nonspecific. Chronologic and clinical diagnostic criteria that are useful in making the diagnosis of DILI are provided in Box 48.4. Chronologic criteria, although usually considered essential, require an accurate clinical history, which is not always possible. Many other difficulties are frequently encountered in making the diagnosis, as shown in Box 48.5. In some instances, clinical criteria37 and laboratory data help to eliminate other potential causes of hepatopathy and point to drug toxicity as the only possible differential diagnosis. Additional tests, such as seric dosage of the drug, can be helpful in some cases. Liver biopsy is not mandatory in the clinical survey, but it may provide substantial information regarding the positive and differential diagnosis of DILI (see later discussion), particularly if liver disease persists, provided that pertinent clinical information is provided and the pathologist is experienced.

Because of variability in both drug exposure and patient susceptibility, prediction of hepatotoxicity depends heavily on the specific type of drug used and patient characteristics (Box 48.6). Some acquired factors may enhance susceptibility to one type of drug but not another. Furthermore, various genetic factors, such as deficiency in certain isoforms of cytochrome P450 (CYP450) or in other enzymatic and metabolic pathways, may contribute to drug hepatotoxicity13 (Table 48.2). In most instances, potentially fatal idiosyncratic reactions cannot be reliably predicted. For example, troglitazone, which was an approved drug for the treatment of diabetes mellitus, is an idiosyncratic, directly hepatotoxic drug that led to an unacceptable rate of acute hepatic failure and was subsequently removed from the market.38–40

Table 48.2

Genetic Factors Contributing to Drug Hepatotoxicity

| Genetic Deficiency | Drugs | Comments |

| CYP2D6 | Perhexiline | Enzyme deficiency: 6% of white population Perhexiline toxicity: 75% of patients are CYP2D6 deficient |

| CYP2C19 | Atrium (combination of phenobarbital, febarbamate, and difebarbamate) | Enzyme deficiency: 3% to 5% of white population Atrium toxicity: all patients have a complete or partial deficiency |

| NAT2 | Sulfonamides, dihydralazine | Transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait High frequency of the slow acetylation phenotype; this deficiency contributes to but is not sufficient for the toxicity |

| Sulfoxidation | Chlorpromazine | Not proven |

| Glutathione synthetase | Acetaminophen | Uncommon condition; deficient subjects are more susceptible to acetaminophen hepatotoxicity |

| Glutathione S-transferase type T | Tacrine | Needs to be confirmed |

| Hepatic detoxification capacity for reactive metabolites | Halothane, phenytoin, carbamazepine, amineptine, sulphonamides | Deficiencies observed in patients and some family members Precise defects are not identified |

| Genetic variations in the immune system | Halothane, tricyclic antidepressants, chlorpromazine, others | Association between several HLA haplotypes and some hepatotoxic drugs |

CYP, Cytochrome P450; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; NAT2, N-acetyltransferase 2.

Causality can be assessed with more certainty if a clear chronologic link can be demonstrated between drug intake and onset of the hepatotoxic event (Box 48.7). Components of the drug signature (e.g., pattern of liver test abnormalities, duration of latency before symptomatic presentation, presence or absence of immune-mediated hypersensitivity, response to drug withdrawal), in conjunction with certain genetic and environmental risk factors, can be formulated into a clinically based scoring system that is predictive of the likelihood of liver injury. The best validated scoring system that takes into account all of these parameters is the CIOMS/Roussel-Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM), which nonetheless has certain imperfections.41 The Naranjo Adverse Drug Reactions Probability Scale (NADRPS) is another simple system based on similar items. Both systems produce a numerical score, indicating that the diagnosis of DILI is definite (or probable), possible, or unlikely. However, a review of 61 case reports of DILI in the PubMed database of the National Institutes of Health over the last decade indicates that in current practice, these scores are used in no more than 25% of published cases.42

Although it is difficult to provide definitive proof of responsibility for a particular offending drug, and because readministration is ill advised, return to normal liver function after withdrawal of the drug is usually good supportive evidence of drug-induced toxicity. Additional tests may be performed on peripheral blood to identify a single causative agent. These may include drug dosing (e.g., acetaminophen), the double-locus sequence typing (DLST) method (which measures the patient’s lymphoproliferative response to growing doses of the suspected causative drug), or the leucocyte migration test (LMT). However, these tests are not simple to perform and not feasible in routine practice.

Prevention of Drug Hepatotoxicity

Assessment of toxicity in human hosts is performed before and after marketing of all drugs. During the early stages of drug development, preclinical studies in animals are mainly useful to detect dose-related predictable hepatotoxicity. Phase I safety studies in human volunteers test toxicity in few patients, after which more patients are exposed during efficacy testing in controlled clinical trials. However, almost 3000 patients need to be included to demonstrate a 1/1000 incidence of DILI, and many drugs that may induce idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity escape detection during preclinical safety assessment and clinical trials.

From a pharmaceutical research perspective, metabolite profiling is essential to rational drug design.43 This issue is addressed, at present, to eliminate molecules that are prone to metabolic bioactivation, based on the concept that formation of electrophilic metabolites triggers covalent protein modifications and subsequent organ toxicity. A cell-based approach for testing of cell viability, mitochondrial impairment, biliary transport, and CYP450 inhibition in the presence of a drug has become useful for the evaluation of putative hepatotoxicity.44,45 The role of mitochondria in DILI, which may be altered through direct toxicity or through immune reaction, seems central, so new drug molecules should also be screened for possible mitochondrial effects. Although such an in vitro approach is pragmatic, it has its limitations, because a linear correlation does not exist between toxicity and extent of bioactivation.

After marketing, surveillance and voluntary reporting of cases is necessary. Routine monitoring of liver enzymes does not seem useful to prevent clinically significant hepatotoxicity in the general population, but it may be interesting in high-risk patients who are taking well-known hepatotoxic drugs. At present, a few simple rules can be applied to help prevent drug hepatotoxicity (Box 48.8). In the future, advances in proteomics, metabolomics, genomics, and bioinformatics may pave the way to “personalized” pharmacotherapy in which the beneficial effect of a drug in an individual is maximized and the toxicity risk minimized.46–48

Treatment and Prognosis

In most cases, no specific treatment is available for DILI, and the main element of treatment is to stop administration of the offending agent, if possible. In most cases of DILI, liver injury is mild, and biologic recovery occurs within days or weeks. However, recovery can take longer with certain drugs.

Because of the wide spectrum of manifestations (from asymptomatic liver test abnormalities to acute liver failure), the difficulties in evaluating the course of disease, and the possibility of spontaneous return to normal liver function because of patient metabolic adaptation, it is difficult to define criteria for cessation or for possible maintenance of the suspected causative drug.

The Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) has developed a five-point system for grading severity based on liver tests, symptoms, jaundice, need for hospitalization, signs of hepatic failure, and death or need for liver transplantation (http://livertox.nih.gov/Severity.html).

Various algorithms for management of DILI have been proposed, based on different biologic thresholds. For instance, jaundice and bilirubin >3 × ULN or prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT-INR) >1.5 × ULN should prompt discontinuation of a drug responsible for cholestatic-type injury. In hepatocellular or mixed disease, ALT >8 × ULN at any one time, or ALT >5 × ULN for >2 weeks, or ALT >3 × ULN and either bilirubin >2 × ULN or PT-INR >1.5 × ULN would lead to drug withdrawal.42

The only example of a well-established specific treatment for drug-induced hepatotoxicity is prevention of severe hepatitis in patients with acetaminophen overdose by administration of N-acetylcysteine within the first 10 hours after consumption of the drug to detoxify reactive metabolites.49

The usefulness of corticosteroids in immunoallergic hepatitis has not been clearly demonstrated but could be tested. In autoimmune-like drug-induced hepatitis, corticosteroids are useful.

Administration of ursodeoxycholic acid has been proposed for long-lasting chronic cholestasis and as symptomatic treatment for the relief of pruritus or as compensation for vitamin malabsorption.13

In the worst-case scenario—drug- or toxin-induced fulminant hepatic failure—liver transplantation may be required.

The prognosis of drug-induced hepatotoxicity is usually excellent when the injury is acute, the cause is recognized, and the offending agent is withdrawn before the onset of severe acute or chronic injury. The term Hy’s law refers to a method of assessing a drug’s potential risk of causing serious hepatotoxicity and mortality. It is based on observations by Dr. Hy Zimmerman about the pejorative value of icteric cholestasis in DILI50: Drug-induced jaundice caused by hepatocellular injury without a significant obstructive component frequently leads to a poor outcome, with a 10% to 50% rate of mortality or transplantation. This fundamental observation is based on the fact that if there is enough hepatocellular damage to impair bilirubin excretion, then there is a potential threat to life.

Clinical elements for the assessment of prognosis include age (typically worse for patients older than 50 years), sex (women being more susceptible to certain drugs), ethnicity and genetic background, nutritional status, multimedication association, and association of other general conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus) or liver diseases (e.g., alcohol abuse, viral disease).

Because of heterogeneous reporting of biopsy findings in the literature, limited data exist on the impact of histology on the outcome of acute DILI. However, some data indicate that the extent of massive and submassive necrosis caused by toxic exposure is linked to a higher mortality rate (>85%), as also observed in other causes of acute liver failure. On the other hand, the presence of hepatic eosinophilia may be associated with a better prognosis in DILI caused by disulfiram and other drugs.

In the setting of chronic hepatitis (as is possible with amiodarone, α-methyldopa, or methotrexate), progression to fibrosis, and eventually cirrhosis, may occur during an extended period. In these circumstances, withdrawal of the drug at a later date does minimize the risk of continued progression, but reversal of fibrosis is rare. An important caveat is the risk of alcohol-induced synergistic injury. Intake of alcohol in the setting of drug-induced chronic hepatitis may exacerbate the severity of injury and cause continued progression toward cirrhosis even after the original offending drug has been withdrawn. Therefore, exclusion of alcohol and other comorbidities is part of the treatment of chronic DILI.

Pathologic Patterns of Toxic Liver Injury

Liver biopsy for adverse drug reaction is one of the most difficult and frustrating situations for the liver pathologist. Liver biopsy is not systematically done in cases of suspected DILI, and most of the time, the decision to perform a biopsy is made because of a complicated clinical situation, such as persistent abnormal liver test results after drug withdrawal, intercurrent medical conditions, multiple potential drug candidates, or a biologic context suggestive of autoimmunity. The list of drugs associated with DILI is very long, but their association with liver injury may be tenuous, and pathologic data are lacking in the literature. When available, histologic features are often nonspecific and heterogeneous among different patients and studies.

An inadequate clinical history or incomplete reporting of drug intake (e.g., nature of the drug, timing) often seriously compounds the problem for the pathologist. Only rarely is an individual histologic sign specific for a particular drug exposure; an example is fibrin-ring granuloma in allopurinol toxicity. Most of the time, a single lesion (e.g., steatosis) can be induced by various toxins. Conversely, one specific type of drug may give rise to different patterns of hepatotoxicity in different patients; for example, hepatitis, cholestasis, granulomas, or a combination of these tissue reactions can be related to phenylbutazone. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can induce either severe hepatocellular or biliary damage, and amiodarone can produce both phospholipidosis and steatohepatitis, albeit by different mechanisms.

However, in the absence of other causes of liver disease, the association of a certain type of necrosis, the presence of a sparse or peculiar inflammatory infiltrate, and the concomitance of steatosis and cholestasis favor the diagnosis of DILI and suggest a mechanism of toxicity (Table 48.3).

Table 48.3

Histologic Lesions Favoring DILI versus Other Liver Diseases and Suspected Mechanisms

| Feature | Mechanism |

| Zone 3 necrosis | Susceptibility caused by CYP450 location |

| Massive necrosis | Intrinsic or idiosyncratic toxicity |

| Necrosis + little inflammation | Intrinsic toxicity |

| Minimal portal inflammation | Intrinsic or idiosyncratic toxicity |

| Many eosinophils | Hypersensitivity reaction |

| Many neutrophils | Inflammatory response of the innate immune system to drug-induced damage of hepatocytes |

| Granulomas | Hypersensitivity reaction |

| Microvesicular steatosis | Mitochondrial injury |

| Mixed patterns | Multiple targets |

| Cholestatic hepatitis | Idiosyncratic toxin |

| Steatosis + necrosis | Indirect toxin |

CYP450, Cytochrome P450; DILI, drug-induced liver injury.

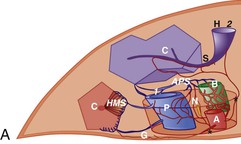

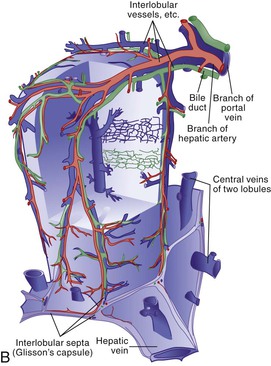

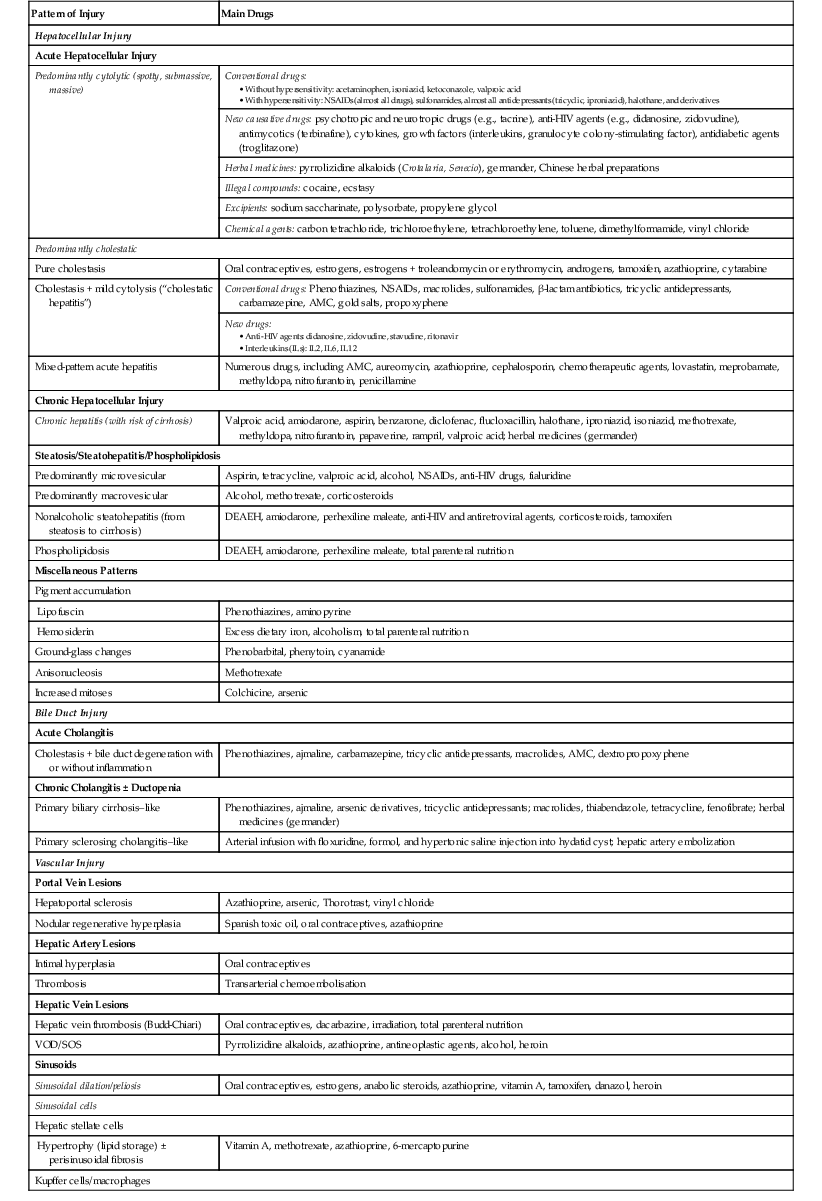

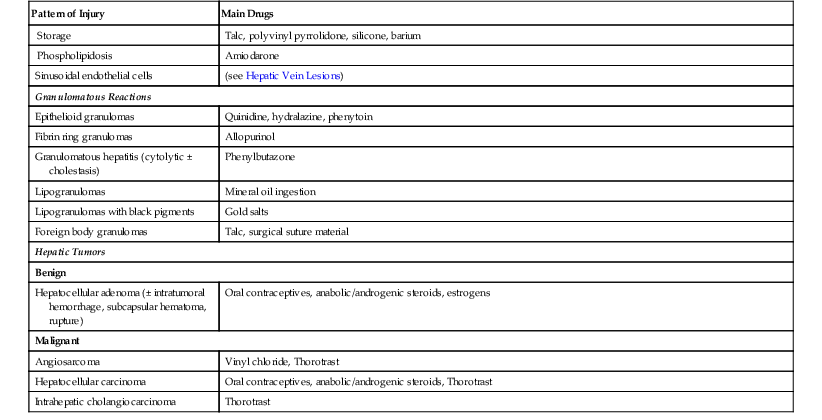

Microscopic analysis of the liver benefits from knowledge of the clinical history and laboratory findings. It is based on a systematic, semiological analysis of all histologic compartments of the liver. Adverse drug reactions affect mainly hepatocytes and bile duct epithelial cells but may also damage sinusoidal cells and vessels in the liver. The spatial organization of vessels, lobules, and sinusoids is illustrated in Figure 48.1. Individual lesions must finally be grouped to define a general and overall pattern of liver injury. The most frequent patterns of DILI are acute hepatocellular injury, predominantly cholestatic injury (of hepatocellular or biliary origin), mixed hepatocellular-cholestatic injury (i.e., cholestatic hepatitis), steatosis pattern, vascular pattern, and neoplastic pattern. These patterns are detailed in Table 48.4, which also indicates examples of causative agents. The corresponding histology is described in the following sections. However, injury patterns are not mutually exclusive, and a mixed pattern of injury may occur in many instances of drug-related hepatotoxicity.20

Table 48.4

Pathologic Effects of Drugs in the Liver

| Pattern of Injury | Main Drugs |

| Hepatocellular Injury | |

| Acute Hepatocellular Injury | |

| Predominantly cytolytic (spotty, submassive, massive) | Conventional drugs: |

AMC, Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; DEAEH, Diethylaminoethoxyhexestrol; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; VOD/SOS, veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome.

Hepatocellular Injury

Acute Hepatocellular Injury

Acute hepatitis accounts for 90% of drug-induced liver diseases. Essentially, this is clinically defined by ALT elevations at least 2 × the ULN, which is a marker of hepatocyte injury (cytolysis). Elevated alkaline phosphatase (AP) is an enzymatic marker of cholestasis because this enzyme is present on the apical membranes of both hepatocytes and bile duct epithelial cells. Acute hepatocellular injury may be predominantly cytolytic (ALT/AP ratio ≥5) or cholestatic (ALT/AP ≤2), or it may occur in a combined form (ALT/AP between 2 and 5).

The mechanisms involved in the development of drug-induced acute hepatitis are complex.5 They are rarely direct (e.g., lovastatin); usually, only massive doses of a foreign substance or extensive metabolism of a particular xenobiotic may lead to direct hepatotoxicity. Drug-induced acute hepatitis mainly results from the formation of hepatotoxic reactive metabolites, which often involve the CYP450 system. The CYP450 system, located mainly in the liver (hepatocytes) and predominantly in the centrilobular zone, metabolizes and eliminates essentially all liposoluble xenobiotics in the environment, as well as most drugs used clinically. However, several xenobiotics are transformed by the CYP450 system into stable metabolites, and many others are oxidized into unstable, chemically reactive intermediates. Reactive metabolites can attack hepatic constituents (e.g., DNA, unsaturated lipids, proteins, glutathione). The end result of this in situ reaction may be either apoptosis or cytolytic necrosis. However, for many drugs, the formation of reactive metabolites is minimal and dose dependent, so that a mild elevation of serum aminotransferases is often seen when the drug is used at therapeutic levels.

The CYP450 isoenzymes are under genetic control; therefore, the hepatic level of a given isoenzyme varies considerably among different people. Furthermore, other agents can enhance the effect of certain drugs. For instance, chronic ethanol ingestion increases a particular isoenzyme of CYP450 (i.e., CYP2E1) that activates acetaminophen.

The binding of reactive metabolites to intracellular or circulating proteins leads to a structural modification that can “mislead” the immune system into mounting an immune attack against its own hepatocytes. Halothane hepatitis is a paradigm for immune-mediated drug hepatotoxicity51,52 because of the presence of autoantibodies in the serum of affected patients. Toxic hepatitis caused only by activation of the host immune system (autoimmunity), without a contribution from direct hepatic metabolism of an exogenous drug, is uncommon. It is usually associated with hypersensitivity manifestations, such as fever, rash, and blood eosinophilia, also known as DRESS (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms).

Genetic factors that affect hepatic drug metabolism and polymorphisms of major histocompatibility complex molecules may explain the particular susceptibility of some individuals to certain drug reactions. These factors have been clearly identified for some drugs (see Table 48.2 and the discussions of individual drugs in this chapter).

Predominantly Cytolytic Injury

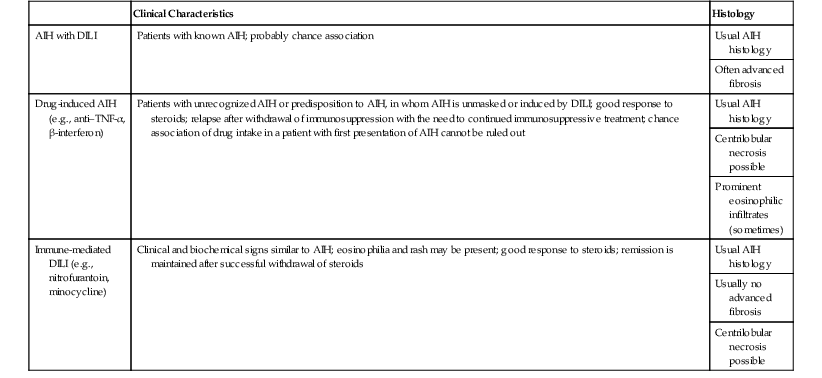

The predominantly cytolytic pattern of drug-induced acute hepatitis resembles acute viral hepatitis but without further specific features. Numerous drugs can cause this pattern of liver injury, including acetaminophen, NSAIDs, psychotropic drugs, a variety of herbal medicines, cocaine, and chemical agents such as carbon tetrachloride (see Table 48.4). Liver damage ranges from mild hepatitis, with rapid improvement after removal of the offending drug, to severe or even fatal liver failure. Hepatocyte death results from the necrotic process or apoptosis or both. Marked lobular inflammation is typically present with toxicity from INH, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, anticonvulsants (phenytoin, valproate), and antimicrobials (sulfonamides, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole [co-trimoxazole], ketoconazole) but is rare or absent with toxicity from acetaminophen, cocaine, ecstasy, or carbon tetrachloride. The differential diagnosis mainly includes viral hepatitis and AIH; some data may favor DILI and may suggest a mechanism of injury (Table 48.5; also see Table 48.3).

Table 48.5

Possible Classification of DILI with AIH Features, Based on Clinical Characteristics and Histology

| Clinical Characteristics | Histology | |

| AIH with DILI | Patients with known AIH; probably chance association | Usual AIH histology |

| Often advanced fibrosis | ||

| Drug-induced AIH (e.g., anti–TNF-α, β-interferon) | Patients with unrecognized AIH or predisposition to AIH, in whom AIH is unmasked or induced by DILI; good response to steroids; relapse after withdrawal of immunosuppression with the need to continued immunosuppressive treatment; chance association of drug intake in a patient with first presentation of AIH cannot be ruled out | Usual AIH histology |

| Centrilobular necrosis possible | ||

| Prominent eosinophilic infiltrates (sometimes) | ||

| Immune-mediated DILI (e.g., nitrofurantoin, minocycline) | Clinical and biochemical signs similar to AIH; eosinophilia and rash may be present; good response to steroids; remission is maintained after successful withdrawal of steroids | Usual AIH histology |

| Usually no advanced fibrosis | ||

| Centrilobular necrosis possible |

AIH, Autoimmune hepatitis; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Modified from Weiler-Norman C, Schramm C. Drug-induced injury and its relationship to autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2011;55;747-749.

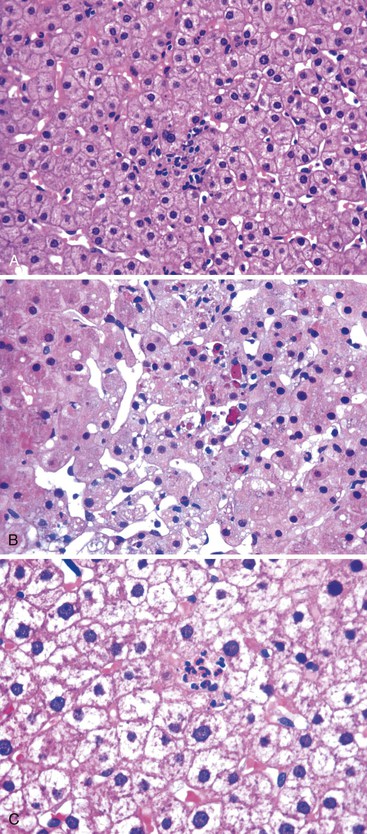

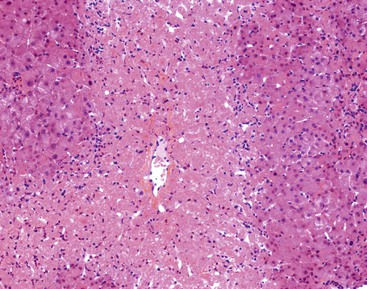

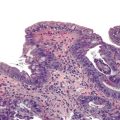

Hepatitis with Spotty Necrosis/Apoptosis.

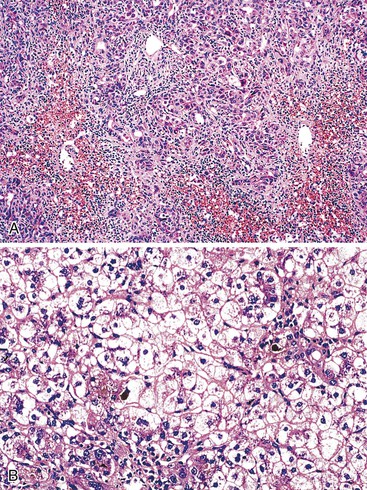

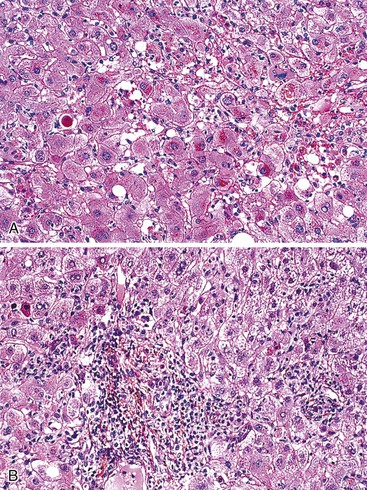

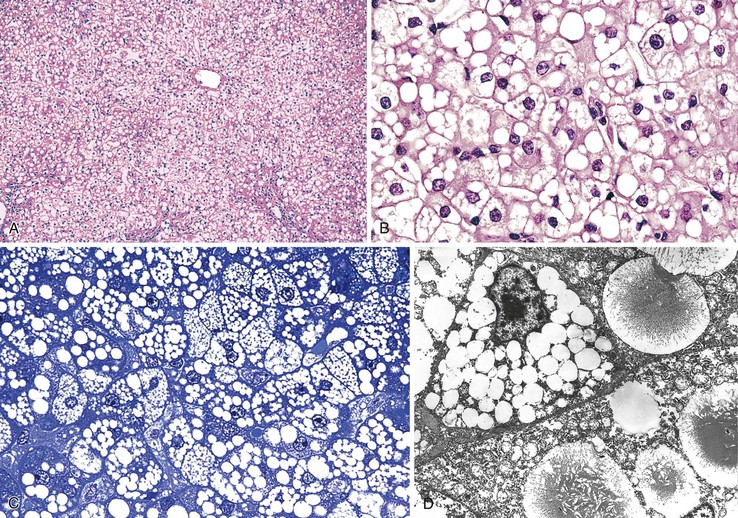

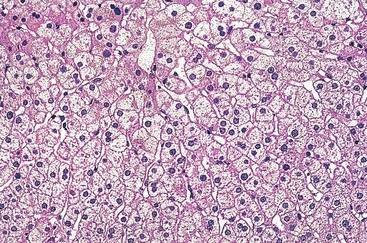

When the mode of hepatocellular injury is predominantly cytolytic, necrosis/apoptosis can affect isolated hepatocytes in the lobule (“spotty” necrosis), resembling viral hepatitis; or, on occasion, it can take a mononucleosis-like appearance. In the former, ballooning or necrotic/apoptotic hepatocytes, scattered or in small foci, are distributed randomly in the lobule, with no or only a few inflammatory cells, leading to an acute hepatitis–like pattern or chronic lobular hepatitis (Fig. 48.2, A and B). INH, sulfonamides, and diclofenac and other NSAIDs can cause this pattern of injury.

Neutrophils and eosinophils (see Fig. 48.2, C) are often also present in the lobule and in some portal tracts. The presence of eosinophils favors a toxic rather than a viral cause of the hepatitis and suggests allergic mechanisms. The presence of prominent neutrophils in portal tracts in a cytolytic hepatitis also favors DILI to other causes. Kupffer cells are often hypertrophied and contain pigments (lipofuscin, hemosiderin), which are best seen with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain, with or without diastase digestion (d-PAS). Sometimes, and especially when the delay between the cytolytic peak and the time of biopsy is great, aggregates of pigmented d-PAS–positive macrophages without any necrosis or apoptosis are the only lesions seen (“resolving hepatitis”). A prominent activation of Kupffer cells, associated with sinusoidal lymphocytosis showing lymphocytes in single files, characterizes the variant form of mononucleosis hepatitis–like injury, as typically observed in hepatotoxicity related to phenytoin (an anticonvulsant agent), paraaminosalicylate, or dapsone.

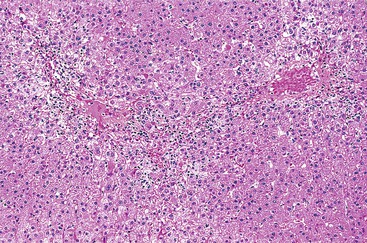

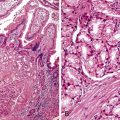

Hepatitis with Submassive Necrosis.

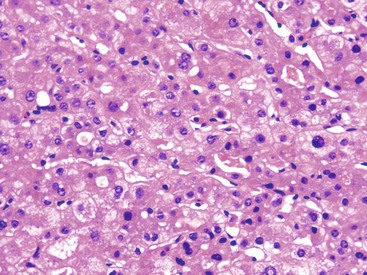

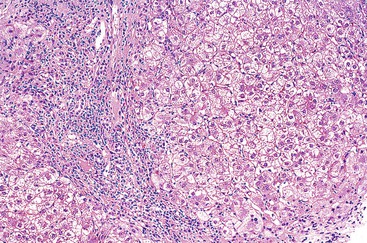

In cases of hepatitis with submassive necrosis, liver necrosis (whether it appears as ballooning degeneration, apoptotic bodies, or coagulative necrosis) is usually zonal and occurs mainly in the centrilobular zones, leading to dropout and loss of hepatocytes, usually with preservation of periportal hepatocytes (Fig. 48.3). Extension of hepatocyte injury to the midzonal areas of the lobule may be strictly zonal and homogeneous, or it may be irregular, leading to the formation of well-demarcated, more or less confluent necrotic areas that contrast abruptly with surviving hepatocyte parenchymal regions. When necrosis is heterogeneous in distribution, it may lead to a maplike or geographic hepatitis (Fig. 48.4). In areas of severe hepatocyte necrosis and collapse, the reticulin framework and endothelial cells are often preserved and are mixed with variable numbers of inflammatory cells and hypertrophied Kupffer cells or macrophages that contain a brown ceroid pigment in their cytoplasm. Significant ductular proliferation may develop around portal tracts with time, as part of a regenerative and healing process. The collapse may lead to liver atrophy, Glisson capsule retraction, and approximation of portal tracts at the microscopic level. Lesions that are heterogeneous in distribution, with irregular regeneration and collapse, can be misleading if a biopsy (usually transjugular) is performed to assess the severity of the lesions and the extent of necrosis and regeneration.

Several types of drugs may lead to this type of necroinflammatory injury, with a generally zonal coagulative pattern affecting almost exclusively the centrilobular areas. Typical examples are acetaminophen and halothane.50 In rare cases such as furosemide hepatotoxicity, one may see predominantly midzonal necrosis. Periportal necrosis is rare and should suggest other drugs such as cocaine53,54 (Fig. 48.5), especially in combination with other toxins (e.g., halogenated hydrocarbons), as well as allylformate or albitocin.

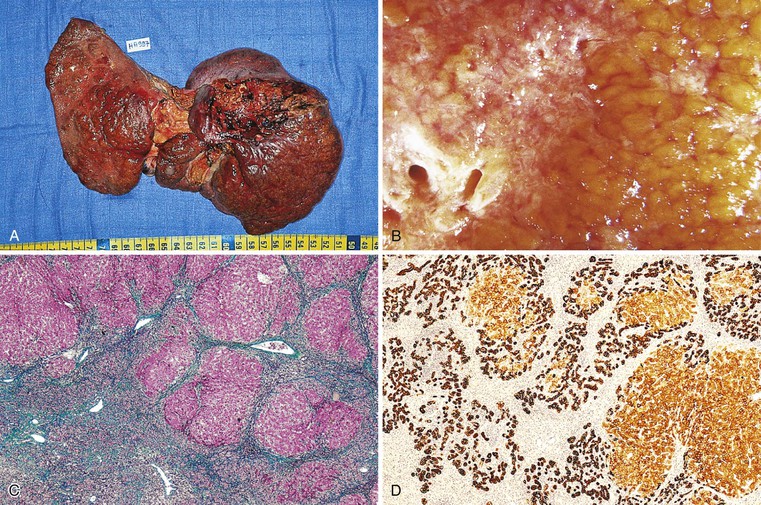

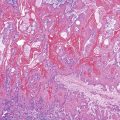

Massive Necrosis.

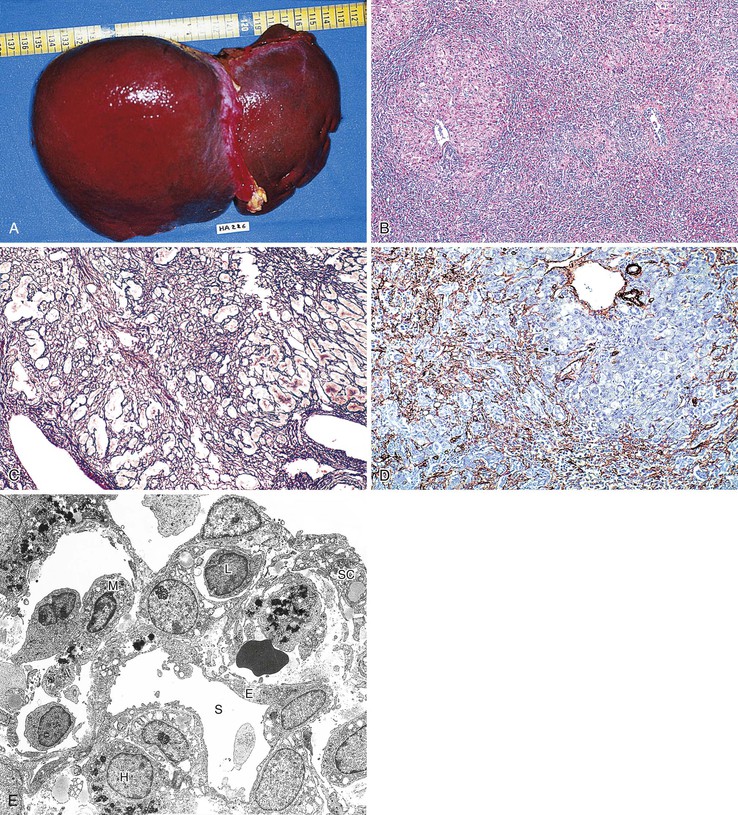

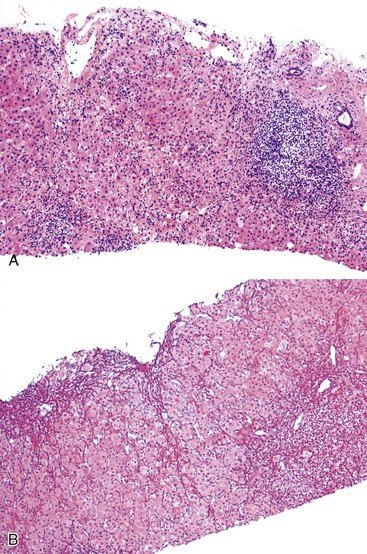

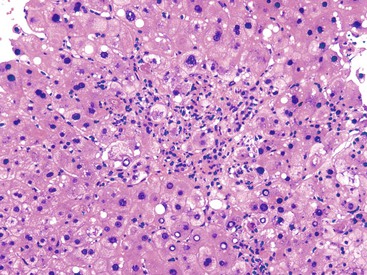

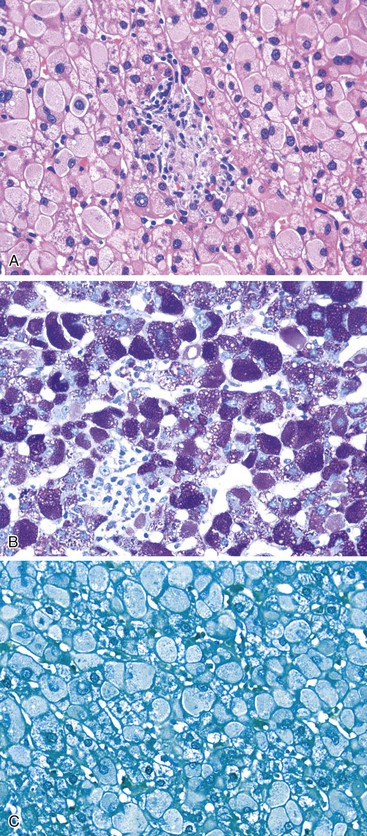

The term massive necrosis is used to describe necrosis of almost all of the normal hepatic lobule, which usually leads to clinically fulminant hepatitis requiring liver transplantation. This type of injury can occur with most of the drugs that cause submassive centrilobular necrosis. The most common example is suicidal or accidental overdose with acetaminophen55,56 (Fig. 48.6) or halothane (Fig. 48.7), but other drugs also can cause this type of extensive, confluent coagulative necrosis (see Table 48.4). This same pattern of severe acute liver damage can result from mushroom poisoning with A. phalloides (Fig. 48.8) and other environmental or illicit drugs such as ecstasy.57–60 This pattern of injury often leaves only a few remaining viable hepatocytes, usually in the periportal region, where surviving cells often exhibit microvesicular or macrovesicular steatosis (see Fig. 48.8, B). The collapsed parenchyma is often intermingled with a prominent bile ductular reaction or proliferation and a few inflammatory cells and Kupffer cells. As a general rule, a marked contrast between the severity of parenchymal necrosis and a poorly developed (mild) inflammatory portal reaction increases the likelihood that the liver injury was caused by a drug reaction, as opposed to a viral infection. Liver atrophy is the rule.

Predominantly Cholestatic Injury

Cholestatic DILI may be caused by hepatocellular toxicity or, less frequently, by biliary lesions (see later discussion). Alterations of hepatobiliary transporters are often implicated in this type of DILI.61 A mixed hepatocellular-cholestatic injury (cholestatic hepatitis) occurs more frequently with drugs than a pure cholestatic hepatocellular injury does, and this type of mixed disease is also discussed later in this chapter. As mentioned earlier, severe cholestasis in DILI must be considered a pejorative prognostic factor.

Bland Cholestasis.

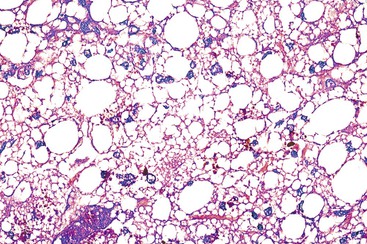

The pattern of bland cholestasis is characteristic of anabolic or contraceptive steroid use. It is typified by the presence of prominent intrahepatic cholestasis, mainly in centrilobular hepatocytes, with the formation of canalicular plugs, corresponding to hepatocanalicular bilirubinostasis. On occasion, feathery degeneration of hepatocytes and liver cell rosettes may develop, especially in cases of prolonged cholestasis. Discontinuation of the offending drug is usually followed by complete recovery.

When cholestasis appears as isolated canalicular bilirubinostasis in a liver biopsy specimen, with little or no inflammation, hepatocyte necrosis, or biliary lesions, the term bland cholestasis is used. In the absence of bile duct obstruction, it suggests DILI (Fig. 48.9, and Table 48.3).

Cholestatic Hepatitis.

Mild hepatocyte ballooning/necrosis or apoptotic bodies, and sometimes portal inflammation, may be associated with cholestasis, in which case the injury is referred to as cholestatic hepatitis (Fig. 48.10 and Table 48.4).

Mixed hepatitis combines conspicuous cytolytic injury and cholestasis (Fig. 48.11) and is frequently associated with immunoallergic manifestations.61 Many drugs can cause either pure cholestasis (mainly steroids) or a mixed pattern of cholestatic hepatitis, including psychotropic drugs,62 antibiotics, antituberculosis drugs,63 and the NSAID diclofenac64 (see Table 48.4). In both instances, the prognosis is usually better than for drug-induced acute hepatocellular hepatitis, as described previously.

A mixed pattern of hepatitis, in which features of both acute cytolytic and cholestatic hepatitis are present, is also considered highly suggestive of drug-induced hepatotoxicity (see Table 48.3).

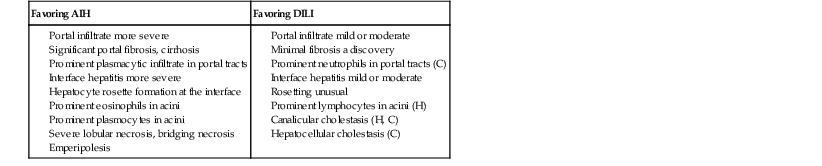

In summary, regardless of the specific pattern of liver injury and the intensity of hepatocellular damage, the presence of predominantly centrilobular injury (particularly if associated with scattered eosinophils) and portal neutrophils argues in favor of drug hepatotoxicity. In addition, mild lobular hepatitis with canalicular cholestasis and an absent or mild portal inflammatory reaction, sometimes unusually rich in neutrophils and eosinophils, may help differentiate DILI from viral hepatitis or AIH (Table 48.6 and Box 48.9; also see Tables 48.3 and 48.5).

Table 48.6

Histologic Features for the Diagnosis of Autoimmune Hepatitis versus Drug-Induced Liver Injury

| Favoring AIH | Favoring DILI |

AIH, Autoimmune hepatitis; C, cholestatic or mixed DILI; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; H, hepatocytic DILI.

Modified from Suzuki A, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, et al. The use of liver biopsy evaluation in discrimination of idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis versus drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2011;54:931-939.

Chronic Hepatocellular Injury

The chronic hepatocellular pattern of liver injury is rarer than acute hepatitis and concerns fewer toxins. Approximately 10% to 15% of cases of acute DILI, either cytolytic or cholestatic, result in chronic disease. However, a histologic pattern of chronic hepatitis does not necessarily imply that the injury has been going on for a long time or will persist. In the criteria from CIOMS, chronicity of toxic liver injury is considered if abnormal liver tests are present for longer than 3 months, but the term chronic liver disease should be used only after histologic confirmation (see Table 48.1).

Histologic evaluation may reveal nonspecific features of chronic active hepatitis, resembling viral or autoimmune disease, with variable degrees of activity and fibrosis (Fig. 48.12). This chronic hepatitis–like histologic pattern includes mixed inflammatory infiltrate (lymphocytes, macrophages, and possibly plasma cells and eosinophils) mainly located in portal and periportal areas, contrasting with the lobular-predominant infiltrate seen in an acute hepatitis–like pattern. Necrosis and apoptosis of hepatocytes is observed both as interface hepatitis and in the lobules. Some steatosis may be associated. Cholestasis, if associated, may suggest a toxic mechanism. A complete medical history is necessary to assess the respective role of toxins versus other comorbidities such as alcohol intake and metabolic or viral disease.

Clinical and serologic tests are usually necessary to eliminate the possibility of a viral hepatitis or AIH and to confirm the effect of a particular hepatotoxic agent (see Box 48.4).

The list of drugs that can induce a chronic hepatitis–like pattern (see Lewis and Kleiner7 and Table 48.4) includes acetaminophen, acetylsalicylic acid, chlorpromazine, clometacin, dantrolene, erythromycin, haloperidol, infliximab, INH, methyldopa, nitrofurantoin, perhexiline maleate, phenytoin, propylthiouracil, tienilic acid (ticrynafen), various statins, and trazodone. Among numerous herbal medicines containing hepatotoxins, some, such as germander (a plant of the Teucrium genus used to treat obesity), may also lead to chronic hepatitis, or even cirrhosis, in addition to acute lesions.65,66

Drug-Induced Liver Injury with Features of Autoimmune Hepatitis

As reviewed by Czaja in 2011,67 hepatitis induced by drugs or herbal medicines can, on occasion, look like AIH on histology and in the clinicobiologic presentation. For example, drugs such as clometacin, methyldopa, minocycline, and nitrofurantoin can mimic type 1 AIH (see Chapter 47) because of histologic lesions and the presence of antinuclear or anti–smooth muscle actin (anti-SMA) antibodies as well as hyperglobulinemia. Chronic hepatocellular injury caused by other drugs such as tienilic acid, iproniazid, and halothane can be accompanied by anti–liver-kidney microsomal type 2 antibodies (anti-LKM2), mimicking type 2 AIH (see Chapter 47), and the pathologic features are usually less severe. Finally, in some cases, one may see morphologic features suggestive of AIH but without autoantibodies (i.e., uracil, sulfonamides, etretinate); this condition is known as autoimmune-like DILI. As detailed later, statins, and particularly simvastatin, atorvastatin, and lovastatin, can induce DILI on rare occasions. In fewer than 50% of the cases, antinuclear and anti-SMA antibodies are observed. Histologic analysis, when performed in these cases, shows features of chronic AIH with occasional eosinophilia.68

There have also been a few reports of AIH-like DILI caused by black cohosh, germander, and ma huang, which are herbal supplements.

As shown in Table 48.5, three situations can occur2: (1) some drugs may trigger real autoimmunity in predisposed patients (drug-induced AIH); (2) DILI with immune mechanisms may induce histologic lesions very similar to those of AIH and may manifest with or without nonspecific autoantibodies (immune-mediated DILI); and (3) in some cases, DILI can occur in a patient with a preexisting typical AIH (AIH with DILI). However, classification between the first two groups remains uncertain and difficult.

It has been suggested that 9% of cases of AIH could be drug-induced AIH. Nitrofurantoin and minocycline would be responsible of 90% of these cases.

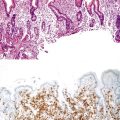

From a clinical point of view, cases of DILI with AIH features have an acute onset and develop mostly in females. They have a profile that is predominantly cytolytic or mixed (with minor cholestasis), but never a pure cholestatic profile. The course is characterized by the absence of relapse after corticoid withdrawal and the absence of cirrhotic evolution.69

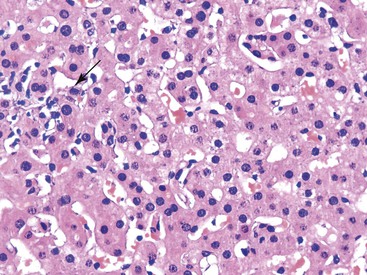

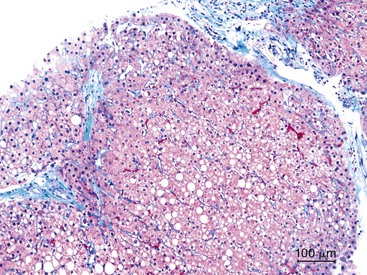

Histologically, the hallmark of DILI with AIH features is the presence of a dense portal infiltrate with numerous plasma cells and eosinophils, associated with a moderate to severe interface hepatitis and possible fibrosis (Fig. 48.13). Whereas cytolytic and cholestatic forms of DILI could be distinguished from idiopathic AIH on the basis of combined histological features,70 it seems impossible to clearly distinguish between drug-induced AIH and idiopathic AIH on the basis of histology alone.69 In the largest series of 24 cases of drug-induced AIH compared with idiopathic AIH, no differences were found concerning grade, stage (except that cirrhosis at baseline was more frequent in idiopathic AIH), portal inflammation, lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, interface and lobular hepatitis, zone 3 and confluent necrosis, or rosette formation.69 In a small subgroup of 7 drug-induced AIH (diagnosis based on the international criteria of 1999 or the simplified criteria of 2008), no difference was found again for the severity of inflammation, and AIH specific findings when comparing the biopsies with those of patients with idiopathic AIH.70 However, in this small series, marked bridging fibrosis (Ishak score at least 4) and prominent intra-acinar lymphocyte infiltration tended to be more observed in idiopathic AIH and DI-AIH, respectively (P = 0.07).

As mentioned previously, the main differential diagnoses of drug-induced hepatitis, whether acute or chronic, are viral hepatitis (e.g., HBV, HCV, Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]) and AIH. However, the inflammatory infiltrate, particularly in the portal tracts, is usually more prominent in viral etiologies, whereas the presence of eosinophils strongly suggests a drug toxicity. Serologic data for viruses or for the presence of autoantibodies are of prime importance in this differential diagnosis (see Chapters 46 and 47). According to Suzuki and associates,70 a combination of histologic features could help first to discriminate DILI from idiopathic AIH (see Table 48.6). However, the concordance rate for the diagnosis among specialized pathologists is less than 30%, so the accuracy of histologic diagnostic has been criticized.11

Steatofibrosis is another pattern for chronic DILI. The offending drugs are the same as those responsible for steatohepatitis, such as amiodarone and methotrexate (Fig. 48.14). These specific molecules are discussed later. Fibrosis is mainly pericellular and perisinusoidal, in zone 3. The respective roles of metabolic syndrome and alcohol abuse may be difficult to exclude before assessing the unique causality of the drug.

Steatosis/Steatohepatitis and Phospholipidosis

Steatosis (fatty liver), steatofibrosis (fatty liver and fibrosis, mostly pericellular in centrilobular areas), and steatohepatitis (fatty liver with inflammation or necrosis and fibrosis) are the three most frequent pathologic manifestations of drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Of course, steatosis and steatohepatitis may be caused by alcohol ingestion or may be a manifestation of central obesity, diabetes, or hypertriglyceridemia with insulin resistance (see Chapter 49). However, drug reactions should always be considered as a potential cause of fatty liver disease. Specific drugs can also induce steatosis and other injury patterns.

Drug-Induced Steatosis and Steatohepatitis

Drugs may induce microvesicular or macrovesicular steatosis, mixed steatosis, steatohepatitis, or a combination of these conditions. Macrovesicular steatosis is a more indolent form of steatosis; it is characterized by the presence of one or more large intracytoplasmic fat droplets that displace the hepatocellular nucleus to the periphery of the cell, often indenting the nucleus. Microvesicular steatosis is clinically the more serious form and is often associated with severe hepatitic dysfunction and cytolysis. It appears as numerous small fat droplets that fill the cytoplasm of enlarged hepatocytes, but without peripheral displacement of the cell nucleus. Special stains for lipid, such as Oil Red O or Sudan black on frozen sections, are sometimes necessary to differentiate microvesicular steatosis from clear cell degeneration; the degree of portal inflammation and cholestasis is usually minimal.

Microvesicular Steatosis.

A large variety of drugs have been incriminated in the pathogenesis of steatosis (see Table 48.4). These include acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) and valproic acid, which are more toxic in children and may lead to the development of Reye syndrome (Fig. 48.15). This severe condition is characterized clinically by the presence of vomiting and neurologic signs with rapid coma, elevated aminotransferases, hyperammonemia, and coagulopathy. Histologically, there is diffuse and predominantly microvesicular steatosis, whereas inflammatory reaction and necrosis are strictly mild. In children, a clear association has been demonstrated with influenza and varicella infections. This association has led to the strong recommendation that salicylates be avoided in children with these viral diseases. In addition, inherited metabolic disorders should always be suspected, and evaluated for, in patients with a Reyelike syndrome. Other drugs that have been associated with steatosis include tetracycline (particularly in pregnant women); several antiviral nucleoside analogues,71 such as fialuridine in hepatitis B72; a variety of anti-HIV drugs, such as didanosine, zidovudine,73,74 and stavudine; and occupational or recreational toxins such as dimethylformamide and cocaine. In some severe cases, microvesicular steatosis may be associated with centrilobular cholestasis or necrosis, for example with valproic acid or anti-HIV retroviral agents (Fig. 48.16).

Because the underlying pathogenesis of drug-induced microvesicular steatosis is related to damage to the intracellular mitochondrial oxidative pathways, acute liver failure or chronic liver injury may ensue. In children, this condition may resemble inherited metabolic diseases, such as congenital enzymatic errors or mitochondrial cytopathic disorders of oxidative phosphorylation.75 In patients with drug-induced microvesicular steatosis, in vitro or in vivo diagnostic studies can be conducted to assess the level of mitochondrial injury.76 These studies include investigation of abnormal mitochondrial morphology, depletion of mitochondrial DNA, anomalies of respiratory chain enzymes and lactate production, and accumulation of drug (e.g., fialuridine) in association with both mitochondrial and chromosomal DNA.44,76,77

Macrovesicular Steatosis.

Glucocorticoids and methotrexate are pharmaceutical agents that cause macrovesicular steatosis as the predominant histologic lesion. This occurs mainly in the centrilobular zone, often surrounding a thickened terminal hepatic vein and often associated with perisinusoidal fibrosis (Fig. 48.17). Drug-induced macrovesicular steatosis may be the only histologic abnormality, or it may be associated with varying degrees of microvesicular steatosis, thereby resembling alcohol-induced steatosis.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal metastasis with 5-fluorouracil is associated with macrovesicular steatosis.

Steatofibrosis

As a form of chronic drug-induced hepatitis, the liver toxicity of methotrexate has been well studied in the context of treatment of both leukemia and psoriasis. Methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity occurs more frequently after long-term treatment with daily small doses at short intervals, and particularly if associated with additional risk factors such as metabolic syndrome or alcohol abuse. Pathologic features of methotrexate toxicity include hepatocytic changes (steatosis, ballooning, nuclear hyperchromasia, pleomorphism, and vacuolation) associated with various degrees of fibrosis or even cirrhosis. Liver biopsies are useful to monitor the presence and progression of liver changes related to methotrexate use. A classification of these lesions has been proposed by Roenigk and colleagues78 (see Box 48.10) and is often used by clinicians, although its reliability has been questioned.79 The association of morbidities such as alcohol intake and metabolic syndrome should also be considered.

Progression of fibrosis to cirrhosis can also occur after exposure to toxins such as arsenic or vinyl chloride or in cases of hypervitaminosis A, in which lipid-overloaded hepatic stellate cells are initially associated with perisinusoidal fibrosis.80

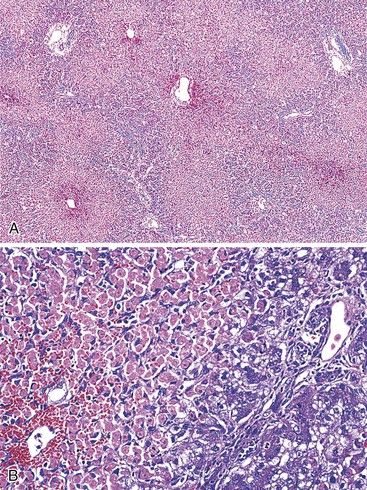

Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Chemotherapy-Associated Steatohepatitis

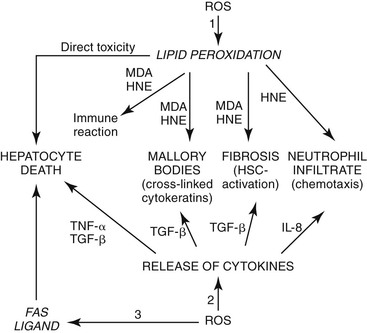

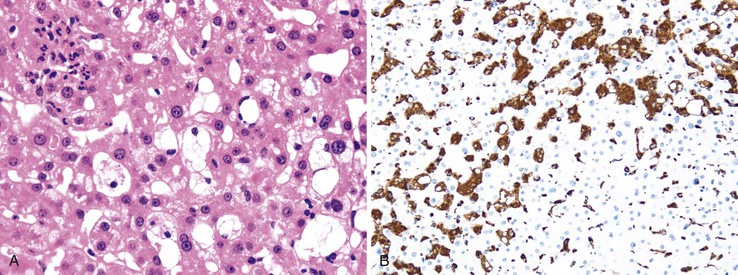

As described in Chapter 49, steatohepatitis refers to the combination of steatosis and hepatocyte degeneration (especially ballooning degeneration and Mallory body formation) combined with an inflammatory infiltrate (polymorphonuclear cells mixed with lymphocytes). Most cases are accompanied by some degree of pericellular fibrosis, which can progress to bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis.81 Some drugs known to cause nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are diethylaminoethoxyhexestrol (DEAEH), perhexiline maleate, amiodarone, and tamoxifen82–87 (Fig. 48.18; see Table 48.4). These four cationic amphophilic compounds have a lipophilic moiety and an amine function that can become protonated. A high intramitochondrial concentration of protonated forms inhibits β-oxidation, which causes steatosis and leads to the mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS can trigger steatohepatitis by lipid peroxidation, cytokine release, and Fas ligand induction. All of these mechanisms can lead to hepatocyte death, fibrosis, and chemotaxis of neutrophils88 (Fig. 48.19). Drug-induced steatohepatitis can coexist with other factors, such as obesity and diabetes.

Preoperative chemotherapy, particularly for colorectal liver metastases, induces regimen-specific hepatic changes that can affect patient outcome. Both response rate and toxicity should be considered when selecting preoperative chemotherapy. In addition to steatosis with 5-fluorouracil, a chemotherapy-associated steatohepatitis (CASH) can occur after treatment with irinotecan, especially in obese patients. Irinotecan-associated steatohepatitis can affect hepatic reserve and increase morbidity and mortality after hepatectomy.89

The single most important factor to aid in the diagnosis of steatotic liver disease is knowledge of the patient’s clinical history. Intake of drugs known to cause hepatic steatosis or steatohepatitis and a thorough appreciation of the patient’s alcohol intake are crucial, in addition to the presence or absence of a metabolic syndrome. Morphologically, differentiating drug-induced steatohepatitis from alcoholic steatohepatitis, or from NASH, is often difficult. Similar to NASH or alcohol-induced damage, drug-induced steatohepatitis shows Mallory bodies, mainly located in ballooned hepatocytes in zone 3 or randomly distributed in the lobule. However, some drugs, such as amiodarone, may lead to involvement of zone 1 hepatocytes.90

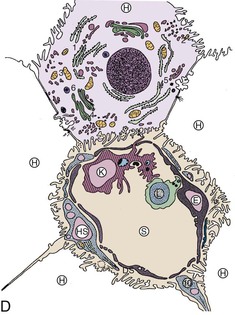

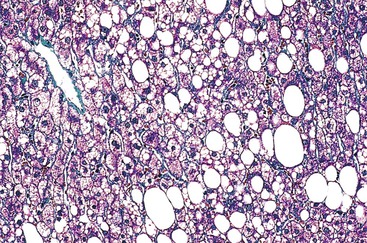

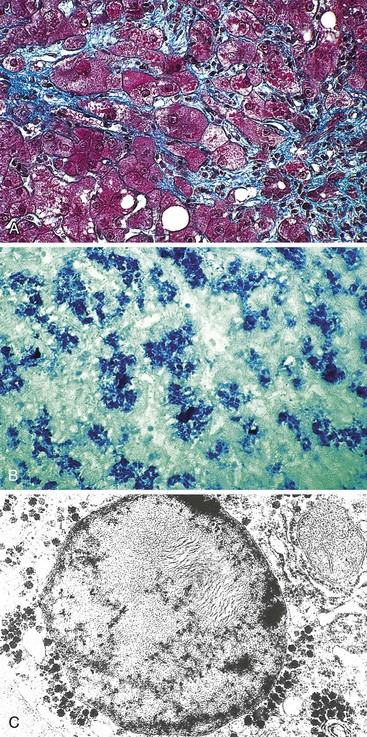

Phospholipidosis

In humans, phospholipidosis has been observed mainly in association with three types of antianginal drugs—DEAEH, perhexiline maleate,5 and amiodarone91—and rarely with some types of antibiotics (Fig. 48.20).92 It can also be induced by parenteral nutrition.93,94 In this particular type of injury (Fig. 48.21), hepatocytes and Kupffer cells are enlarged and appear foamy by light microscopy. On electron microscopy, the cytoplasm of affected cells is filled with characteristic lamellated and membrane-bound bodies, which correspond to phospholipids or gangliosides; the picture resembles the morphologic appearance of Niemann-Pick disease. In contrast to NASH, phospholipidosis is a dose-related change.

The pathogenesis of injury is related to the fact that uncharged lipophilic drugs can easily cross the lysosomal membrane of cells. In the acidic intralysosomal milieu, the drug is protonated, becomes more water soluble, and accumulates inside the lysosomes. Protonated forms of the drug bind with phospholipids, hampering the action of intralysosomal phospholipases. The accumulation of drug–phospholipid complexes generates large lysosomes filled with pseudomyelinic figures. Because of the very slow dissociation of the drug–phospholipid complexes, the drug may be detectable in plasma even several months after discontinuation of treatment.

Miscellaneous Patterns of Hepatocellular Injury

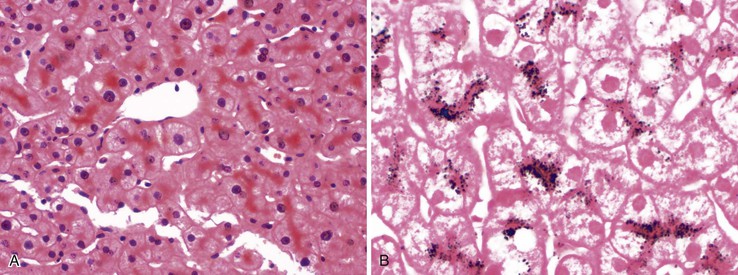

Pigment Accumulation

Lipofuscins accumulate in hepatocytes, particularly in the centrilobular zone (Fig. 48.22, A), during the process of drug-induced damage, such as that caused by phenothiazine or aminopyrine. This pigment may be stained with Fontana stain for melanin (see Fig. 48.22, B) and should be differentiated from bile pigment, which often accumulates in bile canaliculi. In cases of excess dietary iron, alcoholism, parenteral nutrition, or transfusion, hemosiderin can also accumulate in hepatocytes, but it is predominantly observed in sinusoidal lining cells (e.g., Kupffer cells), and it is easily recognized with the use of Perls stain.

Adaptive Changes and Ground-Glass Hepatocytes

A frequent adaptive change of hepatocytes is the development of an abundant pale cytoplasm (Fig. 48.23) because of enlargement of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum induced by long-term treatment with anticonvulsant drugs such as phenobarbital or phenytoin. The terms induced hepatocytes and induction cells are often used for this lesion.

Ground-glass–like inclusions are much rarer in DILI. They appear as pale pink, intracytoplasmic globular structures, often surrounded by a clear halo. They are intensely positive on PAS staining, and the staining disappears with diastase pretreatment (Fig. 48.24). These inclusions correspond to complex material (e.g., glycogen, fragments of lysosomes and other organelles) that accumulates in periportal hepatocytes in patients who consume cyanamide, which is used in alcohol aversion therapy. Similar features have been observed with barbiturates, disulfiram, aziathoprine, phenytoin, and steroids.

Such hepatocytes resemble the ground-glass cells seen with chronic HBV infection, the presence of which is easily excluded by immunohistochemistry with anti–hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) antibodies. This type of ground-glass inclusion may also be seen in Lafora disease (myoclonus epilepsy) and in type IV glycogenosis and fibrinogen storage disease; in some cases, none of these etiologic factors is found. These inclusions resemble polyglucosan bodies described in humans, animals, and experimental models, suggesting a pathogenetic role of disturbed glycogen metabolism, possibly related to polypharmacotherapy,95 particularly with immunosuppressive agents, and more specifically with mycophenolate mofetil.

Anisonucleosis and Increased Mitoses

Anisonucleosis (marked variability in hepatocyte nuclear size) is a consistent finding in biopsy specimens of patients who use methotrexate. Mitoses are strikingly increased (and sometimes rather atypical) in cases of colchicine therapy or acute arsenic intoxication, and this is often accompanied by hepatocyte ballooning, cholestasis, and mild inflammation.96