Toxicology

In a few specific poisonings additional biochemical tests may be of value (Table 60.1).

Table 60.1

Toxins for which biochemical tests are potentially useful

| Toxin | Additional biochemical tests |

| Amphetamine and Ecstasy | Creatine kinase, AST |

| Carbon monoxide | Carboxyhaemoglobin |

| Cocaine | Creatine kinase, potassium |

| Digoxin/cardiac glycosides | Potassium |

| Ethylene glycol | Serum osmolality, calcium |

| Fluoride | Calcium and magnesium |

| Insulin | Glucose, c-peptide |

| Iron | Iron, glucose |

| Lead (chronic) | Lead, zinc protoporphyrin |

| Organophosphates | Cholinesterase |

| Dapsone/oxidizing agents | Methaemoglobin |

| Paracetamol | Paracetamol |

| Salicylate | Salicylate |

| Theophylline | Glucose |

| Warfarin | INR (prothrombin time) |

Measurement of drug levels

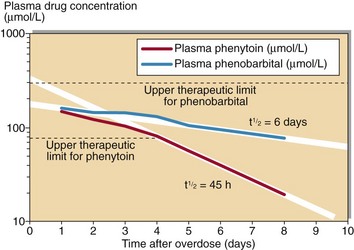

Usually knowledge of the plasma concentration of a toxin will not alter the treatment of the patient. Toxins for which measurement is useful include carbon monoxide, iron, lithium, paracetamol, paraquat, phenobarbital, phenytoin, quinine, salicylate and theophylline. Quantitative analysis will give an indication of the severity of the poisoning and serial analyses provide a guide to the length of time that will elapse before the effects begin to resolve (Fig 60.1).

Treatment

Most cases of poisoning are treated conservatively, while the toxin is eliminated by normal metabolism and excretion. However, when there is hepatic or renal insufficiency, haemodialysis (for water-soluble toxins) or oral activated charcoal may be used. Such measures are usually used only for a small group of toxins including salicylate, phenobarbital, alcohols, lithium (water-soluble), carbamazepine and theophylline. When active measures are used, plasma toxin concentrations should be measured. For a few toxins there are antidotes (Table 60.2).

Table 60.2

| Toxin | Antidote |

| Atropine/hyoscyamine | Physostigmine |

| Benzodiazepines | Flumezanil |

| Carbon monoxide | Oxygen |

| Cyanide | Dicobalt edetate |

| Digoxin/cardiac glycosides | Neutralizing antibodies |

| Ethylene glycol/methanol | Ethanol |

| Heavy metals | Chelating agents |

| Nitrates/dapsone | Methylene blue |

| Opiates | Naloxone |

| Organophosphates | Atropine/pralidoxime |

| Paracetamol | N-acetylcysteine |

| Salicylate | Sodium bicarbonate |

| Warfarin | Vitamin K |

Common causes of poisoning

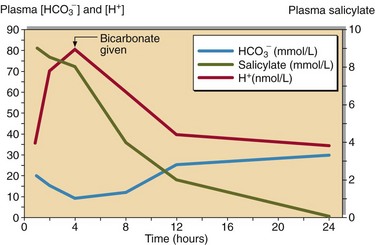

Salicylate poisoning can result in severe metabolic acidosis, from which the patient may not recover. This common drug must be tested for if there is any likelihood that it has been taken. The treatment for salicylate poisoning is intravenous sodium bicarbonate, which both enhances excretion and helps correct the acidosis (Fig 60.2).

Salicylate poisoning can result in severe metabolic acidosis, from which the patient may not recover. This common drug must be tested for if there is any likelihood that it has been taken. The treatment for salicylate poisoning is intravenous sodium bicarbonate, which both enhances excretion and helps correct the acidosis (Fig 60.2).

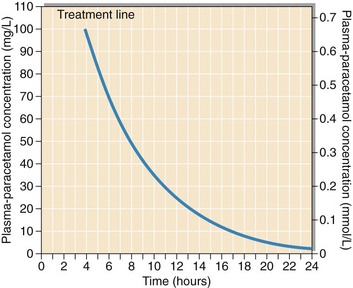

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning causes serious hepatocellular damage and severely affected patients may die of liver failure. In cases of poisoning, the plasma paracetamol concentration, related to time of ingestion, is prognostic (Fig 60.3). A specific therapy, N-acetylcysteine, given intravenously, can prevent all of the hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic effects of paracetamol poisoning. Therapy should be started within 12 hours of ingestion, and hopefully before any clinical symptoms or biochemical changes develop. Patients who abuse alcohol are at particular risk from paracetamol poisoning.

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning causes serious hepatocellular damage and severely affected patients may die of liver failure. In cases of poisoning, the plasma paracetamol concentration, related to time of ingestion, is prognostic (Fig 60.3). A specific therapy, N-acetylcysteine, given intravenously, can prevent all of the hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic effects of paracetamol poisoning. Therapy should be started within 12 hours of ingestion, and hopefully before any clinical symptoms or biochemical changes develop. Patients who abuse alcohol are at particular risk from paracetamol poisoning.

Fig 60.3 Prognosis chart for paracetamol poisoning. (from MHRA Drug Safety Update Sep 2012, (Crown Copyright 2012).

Slow release theophylline preparations in overdose can lead to late development of severe arrhythmias, hypokalaemia and death. In cases of suspected poisoning, the plasma theophylline concentration should be measured and its rise or fall monitored. Measures to aid elimination are of limited effect.

Slow release theophylline preparations in overdose can lead to late development of severe arrhythmias, hypokalaemia and death. In cases of suspected poisoning, the plasma theophylline concentration should be measured and its rise or fall monitored. Measures to aid elimination are of limited effect.

Other serious poisonings are:

Organophosphate and carbamate pesticides, in which cholinergic symptoms persist for some time. Cholinesterase should be monitored.

Organophosphate and carbamate pesticides, in which cholinergic symptoms persist for some time. Cholinesterase should be monitored.

Atropine, causing anticholinergic features, e.g. hallucinations with dry mouth, dry hot skin and dilated pupils. Cases occur most often from ingestion of herbal medicines.

Atropine, causing anticholinergic features, e.g. hallucinations with dry mouth, dry hot skin and dilated pupils. Cases occur most often from ingestion of herbal medicines.

Opiates, where overdose leads to pin-point pupils that rapidly dilate on treatment with naloxone.

Opiates, where overdose leads to pin-point pupils that rapidly dilate on treatment with naloxone.

Cardiac glycosides, both pharmaceutical and herbal, give rise to severe bradycardia.

Cardiac glycosides, both pharmaceutical and herbal, give rise to severe bradycardia.

Methanol and ethylene glycol, poisoning is not uncommon, especially in alcoholics. These toxins are metabolized to formic acid and oxalic acid respectively. Patients develop a severe metabolic acidosis and, in the case of ethylene glycol, hypocalcaemia. Measuring the serum osmolality and calculating the osmolal gap can be useful here. Treatment is with intravenous ethanol to a plasma concentration of around 20 mmol/L. The ethanol is preferentially metabolized and the unchanged alcohols are gradually eliminated in the urine. An alternative is to block metabolism with fomepizole, but high costs limit its use.

Methanol and ethylene glycol, poisoning is not uncommon, especially in alcoholics. These toxins are metabolized to formic acid and oxalic acid respectively. Patients develop a severe metabolic acidosis and, in the case of ethylene glycol, hypocalcaemia. Measuring the serum osmolality and calculating the osmolal gap can be useful here. Treatment is with intravenous ethanol to a plasma concentration of around 20 mmol/L. The ethanol is preferentially metabolized and the unchanged alcohols are gradually eliminated in the urine. An alternative is to block metabolism with fomepizole, but high costs limit its use.