Chapter 21 Total Stapedectomy

The history of surgery for otosclerosis began in the latter part of the 19th century. A group of pioneering surgeons, including Kessel,1 Boucheron,2 Miot,3 Faraci,4 and Passow,5 began to mobilize the stapes. At about this time, Jack6 reported on a series of cases in which he removed the stapes entirely. The unacceptably high rate of inner ear injury and infection led to the abandonment of stapes surgery. As stated by Goodhill,7 “it was probably Siebenmann8 along with Moure9 who closed the door on further stapes surgery at the turn of the century.”

Surgery for otosclerosis was reactivated in 1923, when Holmgren10 bypassed the stapes area by creating a fenestra in the horizontal canal to stimulate inner ear fluids in response to sound, and the fenestration operation was reborn. In 1937, Sourdille11 presented a series of fenestration cases before the New York Academy of Medicine. In 1938, Lempert12 introduced his unique one-stage fenestration technique using his endaural approach and a dental drill to create the fenestra. Surgeons throughout the world clamored to learn his technique, which became the standard. Lempert will forever be known as the father of otosclerosis surgery.

In 1952, Rosen13 reintroduced stapes mobilization for otosclerosis. For a brief time, this technique was widely used and threatened to replace the Lempert procedure. It was soon realized, however, that refixation of the footplate often occurred. Shea14 introduced his technique of total stapedectomy. After removing the total stapes, he covered the oval window with a vein graft and introduced an artificial stapes made of polytef (Teflon) by Treace to make the connection with the incus. This reactivation of stapedectomy by Shea replaced Lempert’s fenestration procedure and Rosen’s mobilization operation, and, with modification, is now used universally throughout the world. We are greatly indebted to Shea for his tremendous contribution to otosclerosis surgery.

SELECTION OF PATIENTS FOR STAPES SURGERY

Indications for Stapes Surgery

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Step 4

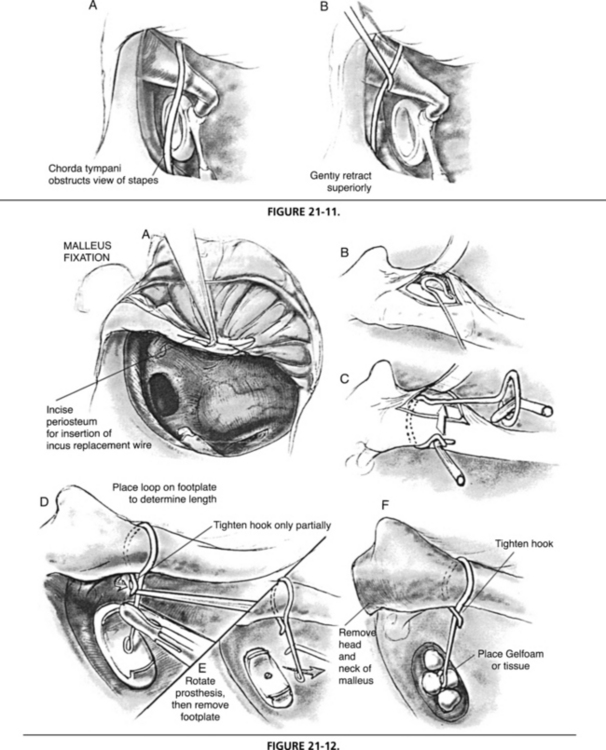

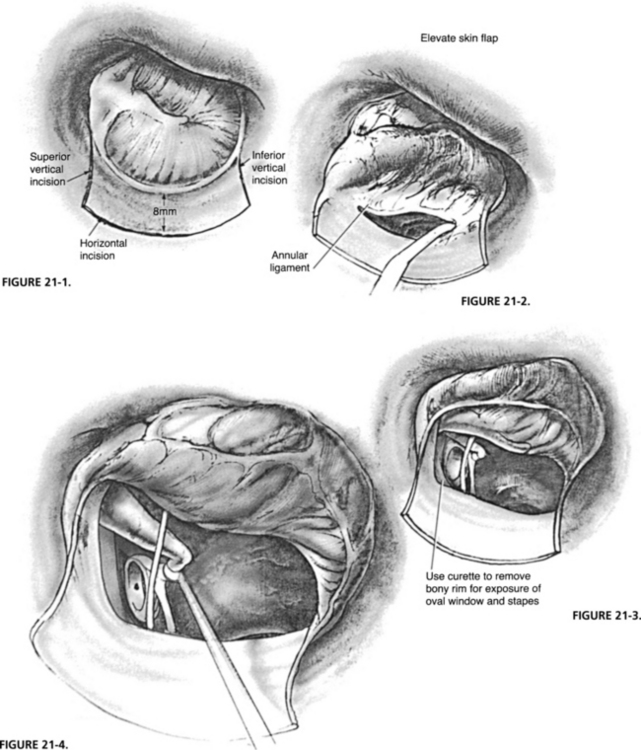

The inferior and superior vertical incisions are made at the 6:30 and 11:30 o’clock positions (Fig. 21-1). The point of the sickle knife is started 1 mm from the edge of the tympanic membrane to prevent a possible tear. It is extended externally approximately 8 mm, and this distance can be confirmed when the curve of the incision knife strikes the edge of the properly inserted speculum. If one extends the incisions further externally, the skin becomes thicker, and more bleeding occurs. Several sweeps are made to ensure that one cuts through the periosteum.

FIGURE 21-1 Inferior and superior vertical incisions.

FIGURE 21-2. Elevating the skin flap.

A curved Rosen needle is used superiorly to elevate the eardrum and identify the position of the chorda tympani nerve (Fig. 21-2). When the nerve is identified, the needle is inserted superiorly to the nerve and carried forward to contact the malleus. This action provides the superior exposure. The needle is used inferior to the chorda tympani to identify the beginning of the tympanic membrane ligament. An elevator is used to lift the ligament inferiorly and to identify the round window. At this point, a cotton ball soaked in the lidocaine/epinephrine solution is placed on the raw surface of the skin flap to lessen the bleeding for a moment. The entire skin flap is elevated anteriorly, and a few drops of lidocaine/epinephrine are dropped onto the mucosa of the middle ear for anesthesia and to control any mucosal bleeding later as work is done in the stapes area.

To visualize the footplate, bone of the posterior scutum is removed. At the upper limit of exposure superiorly, one should observe the lower half of the transverse portion of the fallopian canal (Fig. 21-3). If one can see the beginning of the curve of the body of the incus, a subsequent retraction pocket may develop. The posterior exposure is limited to observation of the stapedial tendon and the attachment of the posterior crus of the stapes to the footplate. If more bone is removed, a posterior retraction pocket may develop. This exposure is usually done with curettes, but a diamond burr may be necessary to expose the posterior portion of the chorda tympani. On completion of this exposure, a square area is created posterosuperiorly. When the curette or the burr is used, the patient under local anesthesia should be forewarned of the noise that is created so there is no surprise to the patient.

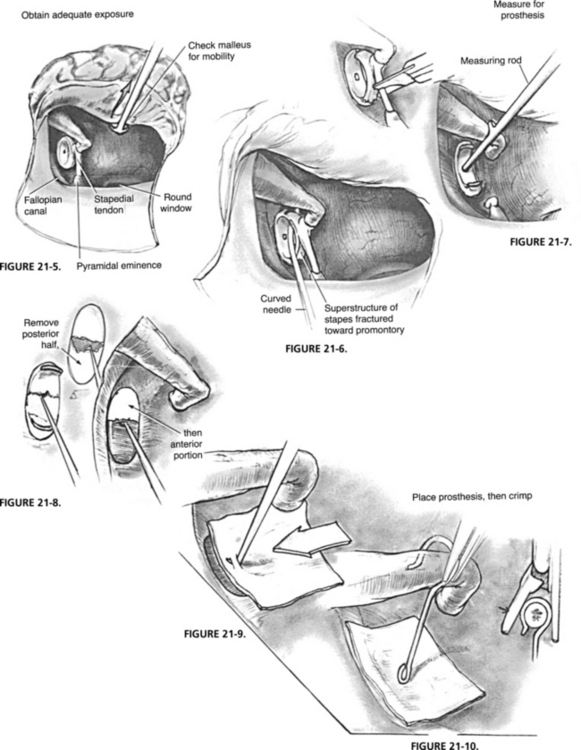

A small, round right angle knife is used now to separate the incudostapedial joint (Fig. 21-4). The intact stapedial tendon helps prevent an inadvertent mobilization from occurring. In this manipulation, a mild pressure and “jiggling” of the knife blade back and forth is used because if strong direct pressure is applied, dislocation of the incus may occur when the joint is suddenly separated. The necessary limits of exposure are the round window inferiorly, the lower half of the fallopian canal superiorly, the stapedial tendon pyramidal eminence and posterior crus posteriorly, and the malleus anteriorly (Fig. 21-5).

FIGURE 21-5 Adequate exposure.

FIGURE 21-6. Fracturing the crura from footplate.

FIGURE 21-7. Measuring for prosthesis.

FIGURE 21-8. Removing the footplate.

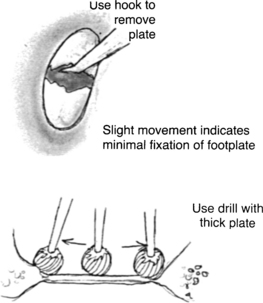

The malleus is now checked to determine its mobility. One in 200 patients has a fixed malleus. If fixed, alternative techniques must be used (described later). The stapedial tendon is cut; then the patient is forewarned that a loud sound is forthcoming. The Rosen mobilizing needle is placed on the superior side of the stapes arch near the neck, and the superstructure is sharply fractured toward the promontory and removed (Fig. 21-6).

The distance from the top of the incus to the thin, fixed footplate is measured (Fig. 21-7). Some surgeons measure from the inferior surface of the incus, and the prosthesis length is made accordingly. The prosthesis length should be checked before it is inserted. The measurement from the outer portion of the incus to the footplate is usually 4.5 mm, but may vary from 3.5 to 5.5 mm.

The membrane is left intact over the footplate because it helps prevent bony chips from dropping into the vestibule. Obtuse, right angle hooks and finally the Hough hoe is used to remove the posterior and then the anterior portion of the footplate, effecting a total removal (Fig. 21-8). Great caution must be used to avoid suction of the perilymph when blood is suctioned from around the oval window. During footplate removal, bone chips or blood entering into the vestibule is left undisturbed.

The previously prepared tissue of choice, measuring about 5 × 5 mm, is grasped with a nonserrated alligator forceps and slipped over the oval window so that it covers all the edges and is positioned superiorly over a portion of the fallopian canal (Fig. 21-9). The prosthesis is inserted with a nonserrated forceps into the center area of the oval window and over the incus (Fig. 21-10). A crimper is used to close the loop on the incus, and the wire is moved toward the lenticular process. The skin flap is then placed back in its normal position, and a small gauze wick is inserted into the hypotympanic area. A cotton pledget is placed over the opening of the external ear canal, and a Band-Aid or two holds the cotton in position, completing the procedure.

INTRAOPERATIVE PITFALLS

Chorda Tympani Nerve

During the procedure, the chorda tympani nerve may be enlarged, or may be in a position to interfere with proper visualization of the stapes area (Fig. 21-11). The chorda tympani may be gently moved superiorly and inferiorly. If it is stretched to the point of a partial tear, it should be severed rather than left partially functioning—the patient has less taste disturbance than when a partially functioning chorda is left intact. One should not sever the chorda if the opposite ear is operated on because a dry mouth and a severe taste disturbance may result.

Malleus Fixation

If the malleus is fixed, and the stapes is mobile, further stapes surgery is abandoned. The incudostapedial joint is carefully separated, and the incus is removed (Fig. 21-12). The head and neck of the malleus are exposed further anteriorly, and the Lempert snipper is used to sever the neck. Fixation usually results from tendon ossification, and tapping with a small chisel on the head of the malleus frees it, enabling removal. Continuity between the mobile stapes and the eardrum may be re-established by reconstruction.

Solid or Obliterated Footplate

By observation, the surgeon cannot determine whether the footplate is minimally fixed at the edges or is obliterated (Fig. 21-13). In each instance, it is necessary to use a cutting burr with a gentle paintbrush-type stroking motion anteroposteriorly. If the slightest give is felt with the drill, minimal fixation and a floating footplate exist. Perilymph escape is noted around the edges. The technique to be used is the same as for the solid floating plate.

1. Kessel J. Uber das Mobilisieren des Steigbugels durch Ausschneiden des Trommelfelles, Hammers und Amboss bei undurchgagikeit der Tuba. Arch Ohrenheilkd. 1878;13:69-88.

2. Boucheron E. La mobilisation de l’etrier et son procede operatoire. Union Med Can. 1888;46:412-416.

3. Miot C. De la mobilisation de l’etrier. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 1890;10:49-54.

4. Faraci G. Importanza acustica e funzionale della mobilizzazione della staffa: Risultati di una nuova serie di operazioni. Arch Ital Otol Rinol Laringol. 1899;9:209-221.

5. Passow K.A. Operative anlegung einer offnung in die mediale paukenhohlenwand bei stapesankylose. Ver Dtsch Otol Ges Versamml. 1897;6:141.

6. Jack F.L. Remarkable improvement of the hearing by removal of the stapes. Trans Am Otol Soc. 1893;284:474-489.

7. Goodhill V. Stapes Surgery for Otosclerosis. New York: Paul B. Hoeber; 1961.

8. Siebenmann F. Traitement chirurgical de la sclerose otique. Cong Int Med Sec Otol. 1900;13:170.

9. Moure E.J. De la mobilisation de l’etrier. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 1880;7:225.

10. Holmgren G. Some experiences in surgery of otosclerosis. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh). 1923;5:460.

11. Sourdille M. New technique in the surgical treatment of severe and progressive deafness from otosclerosis. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1937;13:673.

12. Lempert J. Improvement in hearing in cases of otosclerosis: A new, one-stage surgical technic. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1938;28:42.

13. Rosen S. Restoration of hearing in otosclerosis by mobilization of the fixed stapedial footplate: An analysis of results. Laryngoscope. 1955;65:224-269.

14. Shea J.Jr. Fenestration of the oval window. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1958;67:932-951.