Total Hip Arthroplasty

Patricia A. Gray and Edward Pratt

Each year in the United States approximately 250,000 people undergo a total hip replacement (THR) procedure1 hoping to eliminate persistent pain and to improve their ability to function in daily life. The majority of these people have failed to find relief from their symptoms with conservative medical intervention.

Surgical Indications and Considerations

THR is used to correct intractable damage resulting from osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, avascular necrosis, and the abnormal muscle tone caused by cerebral palsy.2 Nonelective THR procedures are performed for fractures in which open reduction internal fixation is deemed inappropriate.

Contraindications for THR surgery include inadequate bone mass, inadequate periarticular support, serious medical risk factors, signs of infection, and lack of patient motivation to observe precautions and follow through with rehabilitation. Surgery also is contraindicated if it is unlikely to increase the patient’s functional level.2

The prostheses used currently have a projected life span of less than 20 years. Therefore candidates for THR are usually more than 60 years old. Younger patients elect this surgery when their functional status is severely compromised and their pain becomes intolerable. In the case of a fracture, younger patients are treated with an open reduction internal fixation whenever practical. Given the projected life span of current prostheses, younger THR candidates may require a revision surgery later in life.

THR predictably improves function and reduces pain in virtually all patients with disabling disease. Patient satisfaction (with a rating of very good or excellent) regarding pain relief and improvement of function has been measured as high as 98% at 2 years after THR. The long-term survivability rate has been reported as high as 87.3% to 96.5% at 15 years.2–4

Surgical Procedures

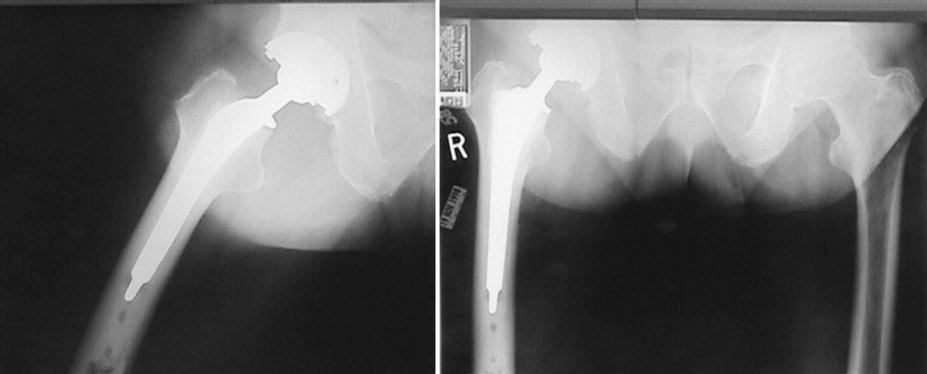

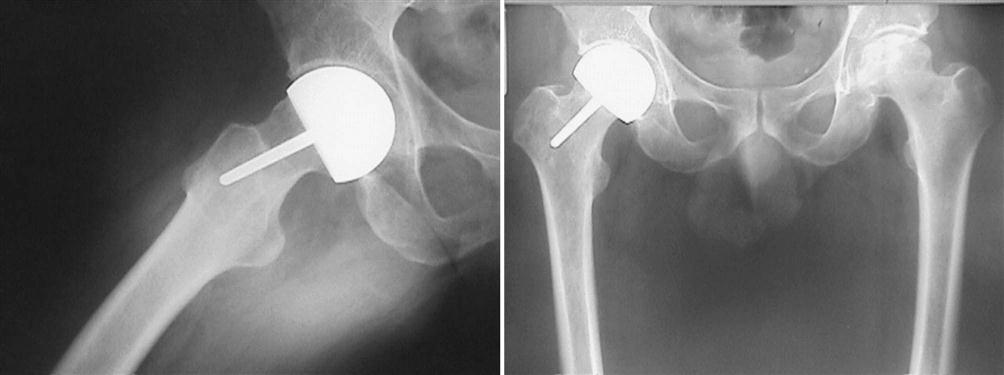

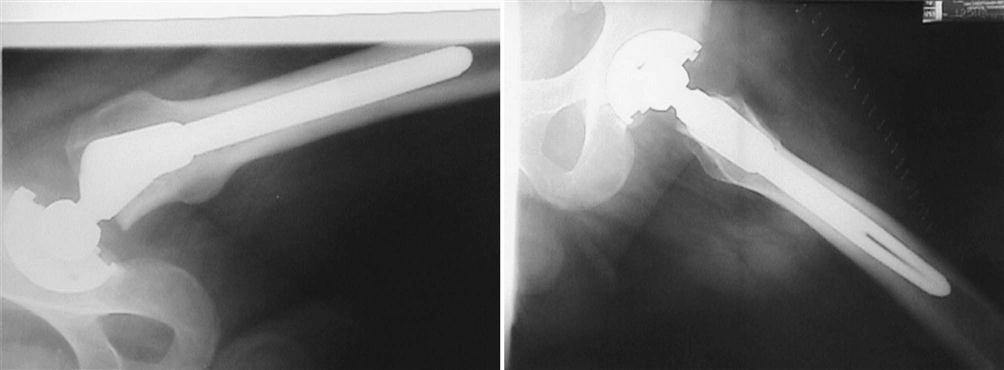

In its essence, THR consists of two parts. First, the remaining arthritic bone and articular cartilage is reamed from the acetabular cup, and a new metal cup with a polyethylene plastic inner liner is press fit into place. Second, the arthritic femoral head is removed and replaced by a femoral head and stem component that is secured into the medullary canal of the proximal femur (Figs. 18-1 through 18-3).

Several aspects of the procedure greatly affect the course of postoperative rehabilitation. First, two approaches are commonly used, each with its own risks and advantages. Second, controversy still exists as to whether it is better to cement or press fit the femoral stem into position.5 Noncemented implants tend to be more expensive and technically demanding to implant; however, they are easier to revise when they fail. It is not yet clear which technique produces the most durable hip replacement. However, it is generally accepted that noncemented implants are best suited for younger, more active patients and more complicated revisions.6 Recently, resurfacing arthroplasty has been recommended for young patients with avascular necrosis, because it preserves bone for later conversion to THR if necessary because of implant failure or pain. Many surgeons believe that noncemented femoral components should not have weight borne on them for 6 weeks, whereas cemented femoral components can support weight immediately after surgery. This has been contested recently, and many surgeons now allow patients with noncemented hips to bear weight from the outset.7 Both approaches have in common the creation of instability around the hip during the early postoperative period. The release of muscle, bone, and joint capsule during accessing of the joint renders the hip vulnerable to dislocation at its extreme ranges of motion. Patient education of “hip precautions” becomes extremely important during early convalescence and is alluded to later in this chapter. Controversy remains as to which approach provides the lowest postoperative dislocation rate, the shortest operative time, and the least blood loss.8 Because of problems with trochanteric nonunion and long-term abductor weakness, the original transtrochanteric approach (in which the greater trochanter or the gluteus medius is completely released) is used most often today in revision surgery. Its main advantage lies in an excellent view of the proximal femoral shaft. The two exposures discussed in the following paragraphs are the posterolateral approach (Gibson) and the anterolateral approach (Watson-Jones).

Posterolateral Approach

The posterolateral approach accesses the hip in the interval between the gluteus maximus and medius. The capsule and short external rotators are released, and the hip is dislocated posteriorly. In extremely large or contracted patients, the surgeon must occasionally release the gluteus maximus and even the adductor magnus at their femoral insertions to translate the proximal femur anteriorly, gaining acetabular exposure. This exposure places traction on the gluteus maximus, medius, and tensor fascia lata. Care must be taken not to place traction on the sciatic nerve or the superior gluteal nerve and artery, which may cause nerve palsy. Repair of the posterior capsule and short external rotators remains controversial, although several recent reports suggest decreased rates of posterior dislocation and heterotopic bone formation when this is done. The posterolateral approach is the author’s personal preference for THR, because it preserves the gluteus medius and minimus, as well as the vastus lateralis, making rehabilitation of these muscle groups easier. It also provides for a quicker normalization of gait in the postoperative period, although this is personal surgeon preference and may be disputed by surgeons who prefer the anterolateral approach.

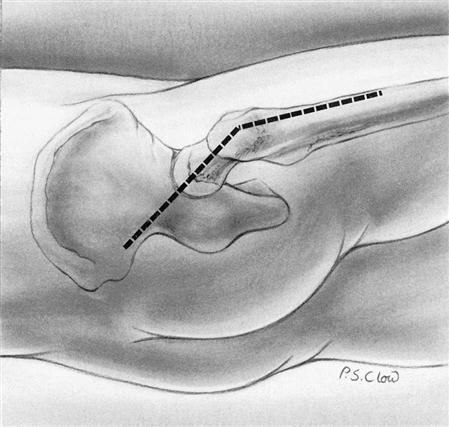

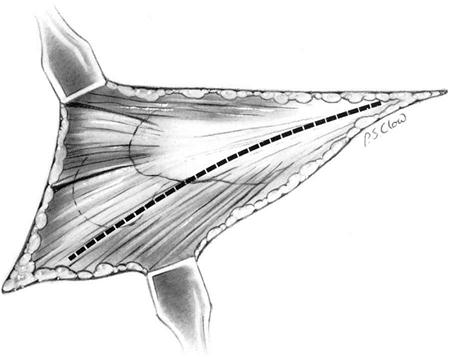

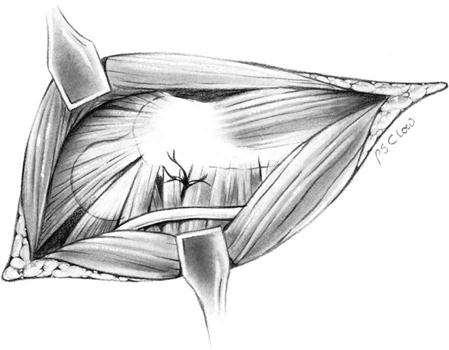

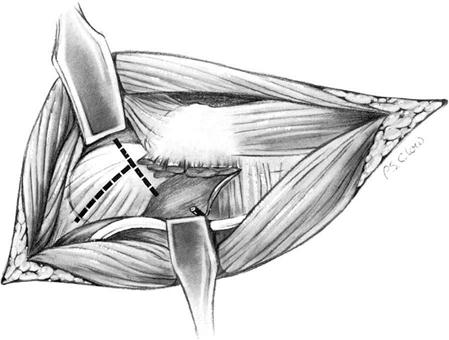

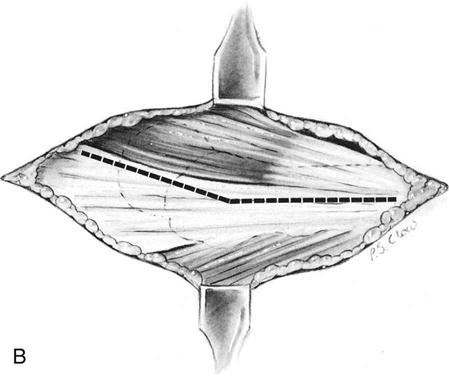

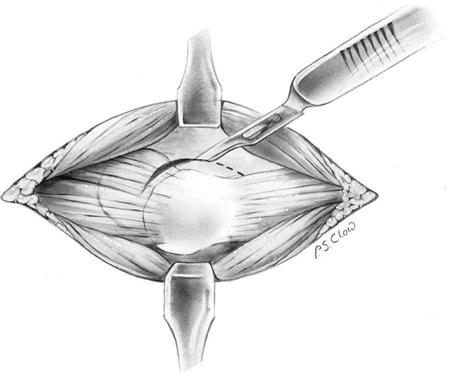

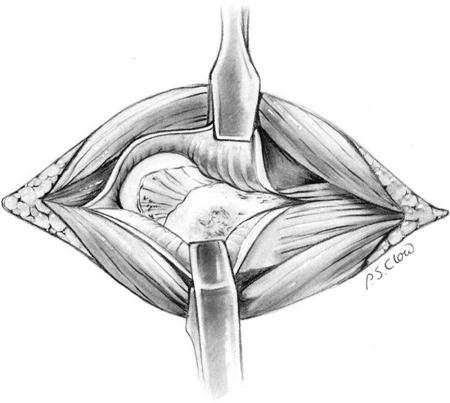

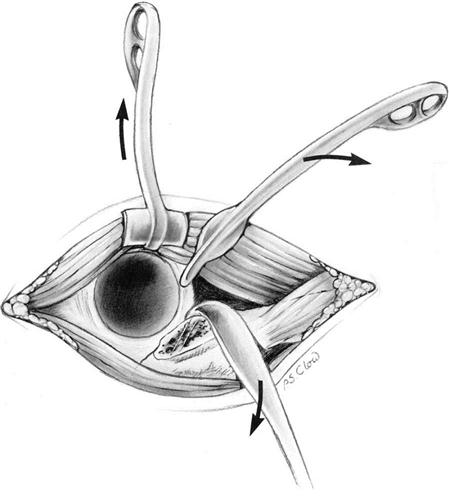

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the affected hip up; the entire limb is washed, prepared, and surgically draped. The incision is begun 4 to 5 inches superior and medial to the top of the greater trochanter (Fig. 18-4). The line of incision runs down to the greater trochanter, then 3 or 4 inches along the course of the posterior femur. The skin and subcutaneous tissues are incised, and the deep fascia is exposed and divided in line with the skin incision (Fig. 18-5). After mobilizing the fascia, the surgeon inserts a large self-retaining retractor to hold the fascia apart. The sciatic nerve is then either exposed or palpated to ensure that it is not being stretched or traumatized (Fig. 18-6). The posterior border of the gluteus medius is identified, as well as the interval between the gluteus minimus and piriformis as they pass into the posterior greater trochanter. This interval is developed and a retractor is placed around the medius and minimus as they are pulled anteriorly. The remainder of the posterior structures is released from the posterior femoral neck and intertrochanteric line, including the piriformis, obturator internus, superior and inferior gemelli, and the superior half of the quadratus femoris (Fig. 18-7). The surgeon releases the posterior hip capsule with the short external rotators, allowing them to retract together (Fig. 18-8). This decreased dissection around the crucial nervous plane under the inferior border of the piriformis leaves a stronger posterior cuff of tissue to repair at the end of the procedure. The limb is next measured for its length between the ilium and greater trochanter, and the hip is posteriorly dislocated. A reciprocating saw is used to cut through the femoral neck, and the arthritic femoral head is delivered from the field. The hip annulus is débrided sharply, and a minimal anterior capsulotomy is performed to help mobilize the proximal femur. As mentioned previously, the surgeon must sometimes go back and release the gluteus maximus, adductor longus, and occasionally even the adductor magnus from the proximal femur so that it can be translated anteriorly. A cobra retractor is placed under the femur and over the front edge of the acetabulum, allowing the femur to be levered anteriorly out of the way of the acetabulum. The acetabulum is then reamed and the acetabular component inserted.

The clinician begins femoral preparation by placing a large retractor under the femur and levering it out of the wound. The surgeon then reams the femoral shaft, increasing the reamer size by 2 mm each pass until good bony contact is made. The intertrochanteric area is then broached or rasped in the same manner until good proximal fill of the femur is obtained. A provisional head is applied, and the joint is placed back together and ranged to check for stability and length. At this stage a stable hip should allow 80° to 90° of flexion, 60° to 80° of internal rotation (IR), and 20° to 30° of external rotation (ER) while being held in neutral abduction. After this the surgeon press fits or cements the implant in place and begins closure. Many surgeons prefer repair of the capsule and short external rotators as a single cuff of tissue held by large No. 2 nonabsorbable sutures through drill holes in the bone. The gluteus maximus and hip adductors are repaired if they were released, and the deep fascia is repaired again with nonabsorbable suture. After closure of subcutaneous tissue and skin, the patient is placed in a triangular-shaped pillow that holds the hip in approximately 30° of abduction. The pillow straps should not be tightened to the point that they compress the common peroneal nerve.

Rehabilitation begins as soon as the patient is coherent. Ankle pumps, quadriceps sets, and leg lifts help reestablish the distal venous circulation, minimizing the risk of thromboembolic disease and helping with postoperative edema. Standing, sitting, and walking can be started on the first day after surgery if hip precautions are followed carefully.

Anterolateral Approach

The anterolateral approach, made popular by Smith-Peterson,3 provides better visibility without the risk of posterior dislocation associated with the posterolateral approach. It avoids the need for postoperative abduction pillows and can allow the patient greater freedom of movement during the initial postoperative period, because hip precautions become less crucial. Because of the reported decreased incidence of posterior dislocation, the anterolateral approach is sometimes preferred in patients who have suffered strokes or those who have cerebral palsy and therefore have a significant muscle imbalance or spasticity that induces flexion and IR of the hip. This approach has been associated with a greater incidence of heterotopic bone formation, greater blood loss, and longer operative times. However, individual surgical expertise seems to have a greater influence on these variables than the exposure chosen.9,10

The anterolateral approach uses the interval between the gluteus medius and tensor fascia lata. The superior gluteal nerve near the ilium innervates both of these muscles. Injury to this nerve can result in a partial or complete abductor paralysis that can vary from a temporary neurapraxia to complete and permanent paralysis. In addition, the femoral nerve can be injured through overretraction of soft tissues in the front of the hip, leaving significant quadriceps weakness. This approach preserves the short external rotators of the hip and prevents direct exposure of the sciatic nerve. The tissues violated include the gluteus medius and minimus, the tensor fascia lata, the vastus lateralis, the referred head of the rectus femoris, the anterior hip capsule, and the iliopsoas tendon.

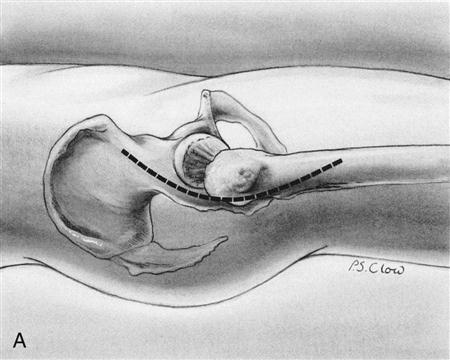

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the affected hip up (Fig. 18-9, A); a lateral incision is made with a slight anterior curvature in its proximal aspect. After dividing the subcutaneous tissue, the surgeon incises the lateral fascia and finds and develops the interval between the gluteus medius and the tensor fascia lata (Figs. 18-9, B, and 18-10). The surgeon must be careful not to extend the incision too far proximally, because the investing nerve of both muscles (the superior gluteal nerve) can be injured, resulting in paralysis of the tensor. The vastus lateralis origin is often dissected off its vastus ridge origin to access the anterior hip capsule fully. The capsule is then bluntly released from the front of the femoral neck to gain access to the hip joint itself (Fig. 18-11). The last deep layer of exposure requires the release of the anterior aspect of the gluteus medius off the greater trochanter and the reflection of the rectus femoris off the anterior acetabulum (Fig. 18-12). The gluteus release can be done either through the tendon or through trochanteric osteotomy (although trochanteric osteotomy has fallen out of favor to some extent because of the incidence of nonunion). After the gluteus release, the hip can be dislocated anteriorly and joint replacement begun much as in the posterolateral approach.

ER and flexion must be avoided postoperatively to prevent dislocation. Hip range of motion (ROM) precautions remain important, especially during the first 6 weeks. Normalization of gait via abductor and quadriceps strengthening remains the focus during early rehabilitation. Pool exercise appears to be extremely helpful in this regard.

Generally a walker or crutches is required for 3 weeks after THR. A cane is used for an additional 3 weeks before unassisted walking is allowed. This varies depending on the age and preoperative condition of the patient. Driving and a return to sedentary activities may be allowed at 3 weeks, and some of the hip precautions can be relaxed at 6 weeks. Improvement in strength and ROM can be expected for as long as 6 months with a motivated patient.

Therapy Guidelines for Rehabilitation

The following text can be used as guidelines for rehabilitation after a THR. Flexibility on the part of the therapist is essential because individual surgeons may impose their own protocols.

The therapist’s role is crucial at the postsurgical stage. Santavista’s study11 revealed that the majority of THR patients report that they received most of their information regarding their surgical recovery phase from physical therapists. These patients will depend on their therapists for encouragement and advice. A therapist should set the patient’s expectations toward independence and wellness early on. Each client should anticipate his or her own unique recovery progression and avoid comparisons with other patients.

Phase I (Preoperative Training Session)

TIME: a few days before surgery

GOALS: To teach THR precautions so that patients will transfer and move safely after surgery and avoid dislocation of the prosthetic joint, to teach a basic exercise program for the postoperative phases of recovery

Many institutions have initiated preoperative THR training sessions to increase their patients’ confidence and reduce the length of their hospital stays. These sessions may take place in the physical therapy department or in the patient’s home through a home care agency’s physical therapist. Educational videos are now available as an adjunct teaching tool.

The preoperative session generally includes an assessment of the patient’s strength (including upper-extremity [UE] potential), ROM, neurologic status, vital signs, endurance, functional level, and safety awareness. Any existing edema, contractures, and leg length discrepancies should be noted at this time, as well as knowledge of the patient’s scar healing ability.12 If the assessment takes place in the patient’s home, check the stairways, hallways, sidewalks and elevators (or lack of) and recommend the necessary safety adaptations (e.g., moving furniture and electrical cords). Evaluate the need for durable medical equipment such as a shower chair, walker, or bedside commode.

Instruction in THR precautions should begin during the preoperative session and be repeated throughout the rehabilitation process as necessary. ![]() The precautions after a posterolateral approach to THR prohibit flexion of the hip past 90°, adduction past the body’s midline, and IR of the hip. After an anterolateral THR, the patient should observe these precautions and avoid hip ER (especially with flexion). A review of proper body mechanics for safe functional mobility at home, along with appropriate postoperative sleeping and sitting positions should accompany the precautions training. Often a patient is able to recite these precautions but will still move in a dangerous fashion. Ask the patient to demonstrate an understanding of these precautions with safe transitional movements and transfer techniques.

The precautions after a posterolateral approach to THR prohibit flexion of the hip past 90°, adduction past the body’s midline, and IR of the hip. After an anterolateral THR, the patient should observe these precautions and avoid hip ER (especially with flexion). A review of proper body mechanics for safe functional mobility at home, along with appropriate postoperative sleeping and sitting positions should accompany the precautions training. Often a patient is able to recite these precautions but will still move in a dangerous fashion. Ask the patient to demonstrate an understanding of these precautions with safe transitional movements and transfer techniques.

Teach the proper use of assistive devices such as walkers and crutches according to the patient’s projected weight-bearing status. ![]() A non–weight-bearing (NWB) order may be given if the prosthesis is noncemented. Maintain adherence to both weight-bearing and ROM precautions throughout the entire rehabilitation process.

A non–weight-bearing (NWB) order may be given if the prosthesis is noncemented. Maintain adherence to both weight-bearing and ROM precautions throughout the entire rehabilitation process.

Postoperative exercises can be taught at this time. These exercises may include the following:

![]() The patient should not perform hip abduction if a trochanteric osteotomy was performed. A dislocation of the THR prosthesis is possible if inappropriate stresses are placed on the new joint.

The patient should not perform hip abduction if a trochanteric osteotomy was performed. A dislocation of the THR prosthesis is possible if inappropriate stresses are placed on the new joint.

Traditional THR exercise programs have become controversial in recent years. The contact pressure on the hip joint during specific activities has been measured and compared with pressure on the hip during gait. Although some practitioners dispute the methodology used, the results of these studies have caused many to question the prescription of some of the standard THR exercises. Consult the surgeon regarding exercise programs that include straight-leg raising.

Strickland found that active hip flexion and isometric hip extension produced the greatest stresses on the joint. Based on these findings, Lewis and the consensus group recommend performing gluteal sets at submaximal levels of contraction to avoid the possibility of dislocation.

Givens-Heiss and colleagues13 found that a maximal isometric hip abduction contraction generated greater peak pressure than both the straight leg raise (SLR) and unsupported gait. The Krebs study14 also found that maximal contraction during exercise generated greater pressure at the hip than did gait. Lewis and Knortz15 recommend that isometric hip abduction be done at submaximal levels based on the results of these studies and suggests slow, supine hip abduction as an alternative.

Phase IIa (Hospital Phase)

TIME: 1 to 2 days after surgery

GOALS: To prevent complications, to increase muscle contraction and improve control of the involved leg, to help patient to sit up for 30 minutes, to reinforce understanding of the THR precautions

Day of Surgery

Postoperative physical therapy (Table 18-1) may begin on the day of surgery when the patient regains consciousness. The patient will be resting in the supine position and wearing thromboembolic disease (TED) hose with the legs abducted and strapped to a triangular foam cushion. To avoid damage to the peripheral nerves, the therapist is expected to check the tightness of the cushions around the patient’s legs.

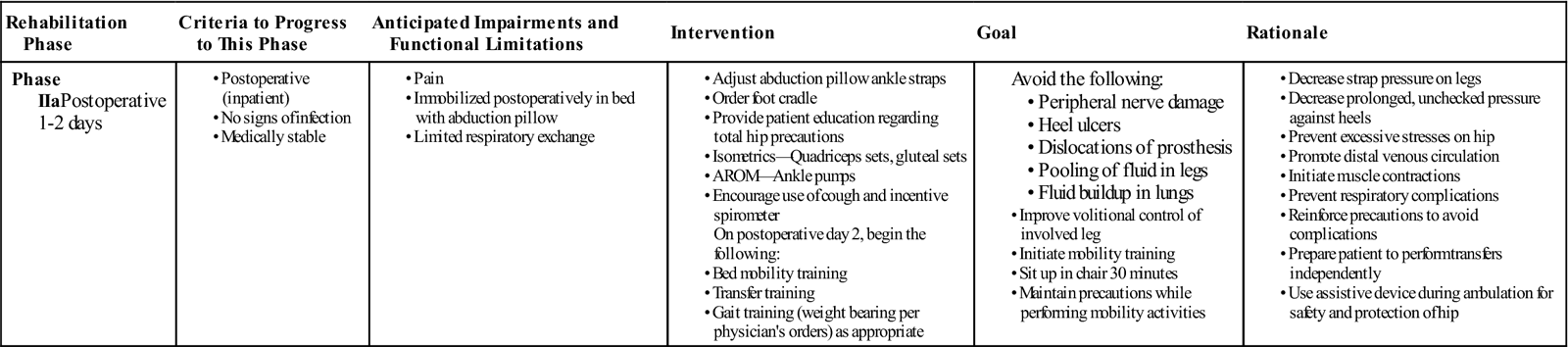

TABLE 18-1

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase IIaPostoperative 1-2 days |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Pulmonary hygiene exercises typically begin immediately after awakening. The patient’s lower-extremity (LE) exercise program also may be initiated at this point with ankle pumps, quadriceps sets, and gluteal sets. The heel booties which are used to prevent bedsores can be removed for these exercises.

Since the client may be groggy and unable to remember the THR precautions at this point, a review is in order. Some may benefit from a sign placed by the bed that lists the ROM precautions. A knee immobilizer placed on the affected leg can reduce the possibility of making dangerous movements.

Repositioning of the patient every 2 hours (with the abductor pillow in place) is critical at this stage to avoid pressure ulcers. Foot cradles are often attached to the foot of the bed to avoid IR of the operated hip and to prevent the heel sores that may develop as a result of pressure from the blankets. Many hospitals’ protocols will assign these functions to the nursing staff and then begin physical therapy intervention on the first day after surgery. All personnel rendering care to the patient should monitor changes in the limb’s vascular and neurologic status closely.

Postoperative Day 1

Acute care physical therapy sessions vary in frequency from one to three times per day and from 5 to 7 days per week, depending on the medical center’s protocol.16 The therapist will proceed after being informed of the surgical approach used, any special precautions, and the patient’s weight-bearing status. Assessment and treatment are conducted at the patient’s bedside while the patient is situated as described previously.

The THR precautions should be repeated at this time. These precautions remain in place until the scheduled follow-up visit with the orthopedist 3 to 6 weeks later. The surgeon may then relax the precautions or decide to continue them for another 6 weeks.

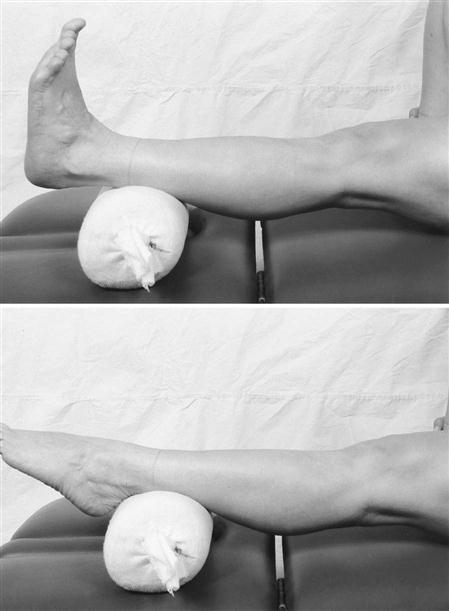

The physical therapist can initiate ankle pumps (see Fig. 18-13), quadriceps sets, and gluteal sets if the patient did not begin them on the day of surgery. Bilateral UE exercises can also begin at this time. ![]() Ankle circles are not indicated, because the patient may inadvertently internally rotate the affected extremity while performing the exercise. As stated previously, submaximal contraction of the muscles is recommended. Ideally these exercises should be repeated 10 times every hour.17 Be aware that some patients may not meet this expectation.

Ankle circles are not indicated, because the patient may inadvertently internally rotate the affected extremity while performing the exercise. As stated previously, submaximal contraction of the muscles is recommended. Ideally these exercises should be repeated 10 times every hour.17 Be aware that some patients may not meet this expectation.

Transfer training begins by assisting the patient to move safely from a supine to a sitting position and then from sitting to a standing position while observing precautions. Frequently patients are struggling with pain and anxiety and need encouragement. The physical therapist should allot a considerable amount of time for this task and emphasize the use of the UEs when shifting weight. ![]() Avoid pivoting on the operative leg. Surgeons usually allow a patient to transfer to an appropriate bedside chair and sit up as tolerated,

Avoid pivoting on the operative leg. Surgeons usually allow a patient to transfer to an appropriate bedside chair and sit up as tolerated, ![]() rarely more than 30 to 60 minutes. The therapist then supervises the return to bed.

rarely more than 30 to 60 minutes. The therapist then supervises the return to bed.

![]() If a patient is not complaining of excessive pain, fatigue, or dizziness, then gait training may begin on the first postoperative day. More frequently, gait training begins on day 2.

If a patient is not complaining of excessive pain, fatigue, or dizziness, then gait training may begin on the first postoperative day. More frequently, gait training begins on day 2.

Postoperative Day 2

Treatment on postoperative day 2 includes a review of the previous day’s activities. The client must maintain hip ROM within the physician’s recommended guidelines. The physical therapist expands the exercise program to include heel slides and isometric or active assistive hip abduction. Short arc quadriceps sets may require active assistance at this time. Again, submaximal force is recommended for isometric hip![]() abduction. Assistance from the therapist may be necessary for some exercises. The use of verbal cues such as “point the moving knee or big toe toward the ceiling” to avoid rotation of the leg may also be helpful.

abduction. Assistance from the therapist may be necessary for some exercises. The use of verbal cues such as “point the moving knee or big toe toward the ceiling” to avoid rotation of the leg may also be helpful.

Gait training usually begins during this session. The patient’s assistive device is adjusted to the client’s height before instruction and practice begin. Older patients are typically issued a front-wheeled walker. Younger patients may be issued crutches and instructed in the three-point crutch pattern. Patients who have undergone bilateral THR are instructed in the four-point crutch pattern.

![]() The weight-bearing status after a noncemented THR is up to the surgeon’s discretion. A NWB order on the operative extremity may be in effect for several weeks. Most patients with cemented prostheses are instructed to bear weight as tolerated at this stage.

The weight-bearing status after a noncemented THR is up to the surgeon’s discretion. A NWB order on the operative extremity may be in effect for several weeks. Most patients with cemented prostheses are instructed to bear weight as tolerated at this stage.

Complex surgeries may require more caution. When the postoperative order calls for only touch down weight bearing (TDWB), taping a “cracker” to the sole of the patient’s operative forefoot with instruction not to break the cracker can be helpful in teaching this concept. Stepping onto a bathroom scale with the affected extremity helps the partial–weight-bearing (PWB) patient to determine the appropriate amount of pressure (usually 50% of body weight or less) to be put on that leg. Those who are still experiencing difficulty can practice weight shifting at the parallel bars before using a walker.

Patients who have undergone THR frequently walk with the affected leg in abduction. Encourage normalization of their gait pattern early in the recovery phase. Most facilities set a short-term goal for discharge at walking on a level surface for 100 feet with an appropriate assistive device.

Phase IIb

TIME: 3 to 7 days after surgery

GOALS: To promote transfer and gait independence (using assistive devices as indicated), to reinforce THR precautions, to discharge to home

Postoperative Day 3 (Until Discharge)

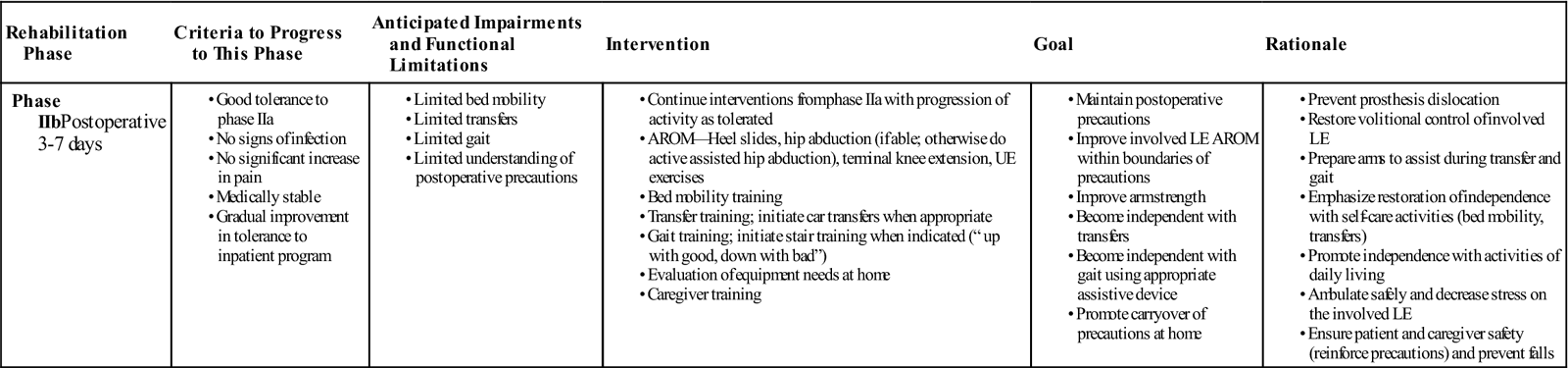

Patients are often moved from the acute care section to a rehabilitation center or skilled nursing facility on day 3 (Table 18-2). Some patients (usually those who are younger and more fit) may be discharged to home care at this time.

TABLE 18-2

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase IIbPostoperative 3-7 days |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

AROM, Active range of motion; LE, lower extremity; UE, upper extremity.

Treatment at the rehabilitation center is conducted in the physical therapy gym. Stair training generally begins on day 3. A step-to gait pattern with minimal weight bearing on the affected leg is taught for ambulation on even surfaces; on steps or stairs, the patient leads up the stairs with the unaffected leg and down the stairs with the affected leg. Patients should become comfortable climbing the number of stairs demanded by the home situation. When the patient is not competent with stair climbing, arrangements are sometimes made for the patient to live on the ground floor.

Refinement of these skills continues daily at the rehabilitation center until the time of discharge. By the discharge date, family members or other caregivers must be trained to assist the patient safely whenever necessary.

Common discharge criteria for THR are as follows:

• The patient is able to demonstrate and state the THR precautions.

• The patient is able to demonstrate independence with transfers.

• The patient is able to demonstrate independence with the exercise program.

• The patient is able to demonstrate independence with gait on level surfaces to 100 feet.

• The patient is able to demonstrate independence on stairs.

Written instructions with illustrations pertaining to these criteria are included in a discharge packet for home use. Patients are typically discharged between 5 to 10 days after surgery. Zavadak and colleagues18 found that independence in functional activities required the following number of physical therapy sessions:

However, the therapist’s expectations should not be unduly influenced by statistics. Munin and colleagues19 found that fewer than 40% of patients who undergo THR are independent in performing all the basic tasks at the time of discharge from the rehabilitation center. Approximately 80% of patients were at the supervision level of performance. Advanced age, solitary living conditions, and an increased number of comorbid conditions were the factors that predicted the duration of a patient’s treatment stay.19

Phase Iii (Return to Home)

TIME: 1 to 6 weeks after surgery

GOALS: To evaluate the safety of the home, to assure patient independence with transfers and ambulation, to plan the client’s return to work or previous community activities as appropriate

Home Care Phase

Physical therapy home assessment usually occurs within 24 hours after hospital discharge. The elements to be assessed are those listed in the preoperative section, with the addition of the status of the surgical incision. The number of visits authorized by the patient’s insurance company may limit the goals set by the therapist. Medicare coverage at this stage is restricted to patients who are homebound or severely limited in their ability to go out. Most patients are no longer homebound after 3 to 4 weeks.

Because managed care insurance has placed constraints on the number of nursing visits allowed, physical therapists are now being trained to remove staples, traditionally a nursing function. Staple removal normally occurs 12 to 14 days after surgery.

After hospital discharge, expect to advise the patient regarding appropriate sitting and sleeping positions, furniture adjustments, and other home safety issues such as slippery rugs or strung-out electrical cords. A home care agency admission assessment includes a review of patient medications. Check to see if the patient and/or caregiver have the appropriate medications in the home and are taking them as prescribed.

A postural assessment should be done and contractures noted should be addressed through a cautious stretching program. Careful straight leg hamstring stretches done with the therapist’s assistance may be added to the supine exercise series (not to exceed 90° of hip flexion). The Achilles tendon stretch can be done at a kitchen countertop, walker, or at the wall. Closed kinetic chain exercises (with involved leg firmly planted on the ground or on exercise equipment), such as heel raises and minisquats, can also be done at the countertop. Open chain exercises done while standing at this location include hip flexion, hip abduction, and hip extension. Sidestepping is a functional abduction exercise that stimulates both sets of glutes and engages eccentric hip rotators in stance phase.

Frequently patients will substitute hip flexion for true abduction. They have difficulty firing the glut medius and glut minimus because of chronically flexed posture. Good hip extension and good concentric and eccentric control of the hip rotators are needed for a normal gait pattern.20 Lunges, done standing in a doorway with elevated arms on either side of the door frame, can effectively stretch the plantar flexors, hip flexors, arms, and trunk while strengthening the opposite LE quads.20 Stronger, more mobile patients may be able to assume a prone position to stretch shortened hip flexors.

Progress the client to wall slides done with the patient’s back resting against a wall and feet placed about 12 inches in front of the wall. Balance training and a core/trunk strengthening program to reinforce good postural habits may begin now or in the outpatient clinic depending on the patient’s level of progress. Exercise equipment already in the patient’s home may be added to the existing program if it can be used safely.

Shoes often adapt in shape to the stresses imposed by an abnormal gait pattern and may encourage a return to the old pattern if worn after THR surgery. Replace the patient’s old misshapen shoes if possible.

Progression from the use of a front-wheeled walker or crutches to a single-point cane usually occurs at 3 to 4 weeks after surgery. Occasionally, a four-point cane is used as an interim device. Use of the cane is usually discontinued 3 to 4 weeks later. The patient should walk safely on level and sloped surfaces, jagged sidewalks, curbs, and stairs before discharge.

Enough strength may have been recovered to allow step-over-step stair climbing during the home phase. At first, the patient can practice stepping up onto books or other household items that provide a stable, shallow rise. A modified lunge with the affected extremity placed on the upper step is another helpful prestair climbing exercise.

Driving is allowed 3 to 6 weeks after surgery at the orthopedist’s discretion. Permission may be given sooner, depending on the patient’s lifestyle requirements and rate of progress. Instruct the patient in getting on and off a bus or in and out of a car safely. A clean plastic trash bag placed over the seat of a car provides a surface that allows the patient to glide-pivot around on the seat to assume the rider’s position more easily.

Outpatient Clinic

Physical therapy intervention often ends with the home care phase. Patients with physically demanding lifestyles may require additional strength and endurance training. Some patients are referred to the clinic because of lingering gait problems, others because they didn’t meet homebound requirements at the time of hospital discharge. The outpatient therapist should check with the surgeon for the status of precautions and activity level before designing an aggressive exercise program.

The patient reassessment at this point includes posture, balance, strength (both concentric and eccentric at the hips), gait pattern, and core control. A stretching and exercise regime begun in the home or hospital can be expanded upon in the clinic. Continue to improve posture with trunk and hip flexor stretching. Normalize the gait pattern with weight shifting and hip strengthening exercises. Core strengthening to support good posture should be present in the program. Pool exercise is recommended after THR. Equipment such as a treadmill, exercise bike, and elliptical cross-trainer can be incorporated into a home program so that the patient may continue at his or her own gym later on.

As in home care, the goals at this stage depend on the number of visits authorized by the patient’s insurance company. Quick independence with a home exercise program should be encouraged.

After Rehabilitation Intervention

The surgeon will determine the patient’s return-to-work date. Job modification may be needed and some may not be allowed to return to their previous jobs. Heavy manual labor is not permitted after THR surgery and vocational counseling may be necessary.21

High-impact sports such as running, waterskiing, football, basketball, handball, karate, soccer, and racquetball traditionally have been contraindicated after THR![]() .22 The results of the 2007 Survey23 also list snowboarding and high-impact aerobics as “not allowed.” Activities “allowed with experience” are downhill skiing, cross-country skiing, weightlifting, ice-skating/rollerblading, and Pilates.23 The sports “allowed” by the 2007 Survey20 respondents are swimming, scuba, golf, walking, speed walking, hiking, stationary cycling, bowling, road cycling, low-impact aerobics, rowing, dancing (ballroom, jazz, square), weight machines, stair climber, treadmill, and elliptical.23 Doubles tennis is considered less stressful than singles tennis.14 The survey results were undecided regarding singles tennis and the martial arts.

.22 The results of the 2007 Survey23 also list snowboarding and high-impact aerobics as “not allowed.” Activities “allowed with experience” are downhill skiing, cross-country skiing, weightlifting, ice-skating/rollerblading, and Pilates.23 The sports “allowed” by the 2007 Survey20 respondents are swimming, scuba, golf, walking, speed walking, hiking, stationary cycling, bowling, road cycling, low-impact aerobics, rowing, dancing (ballroom, jazz, square), weight machines, stair climber, treadmill, and elliptical.23 Doubles tennis is considered less stressful than singles tennis.14 The survey results were undecided regarding singles tennis and the martial arts.

Patient compliance with home exercise programs is often questionable after the first few weeks and especially after discharge from therapy services. No agreement seems to exist among surgeons as to how long exercise programs should be continued. The surgeon may release the patient from the home exercise program at his or her discretion.

Sheh and colleagues24 state that flexion showed the slowest rate of recovery in diseased hips. Persistence of weakness was noted in all patients for at least 2 years after hip surgery despite the return of normal stride and phasic activity of muscles. Gluteus maximus or minimus weakness can result in aching near the hip during endurance activities. Sheh states that muscular weakness reduces the protection of the implant fixation surfaces during endurance activities. This may contribute to higher loosening rates reported in active patients.24 Therefore, therapists should encourage long-term continuation of exercise programs when this does not contradict the surgeon’s orders.

Troubleshooting

The THR procedure has been refined so that patient progress is now fairly certain and predictable. However, most complications call for a referral back to the surgeon. Examples include the following:

Many times the therapist is the first to see a developing complication; therefore, good communication with the surgeon is extremely important. Leg length discrepancy is an example. The patient can continue gait training with a temporary shoe insert or with shoes of different heel heights. The surgeon may later prescribe a permanent orthotic. Persistent edema may be treated with medication. Patients should be advised to elevate their legs, rest more often, wear TED hose, pump their ankles, and apply ice to swollen areas. Pain flare-ups in unaffected areas of the body are usually managed with medication. Possible side effects of the medication include nausea, constipation, and hypertension. The therapist can assist in pain reduction with modalities, exercises, and positioning. Significant abnormalities should always be reported to the surgeon.

Conclusion

A rapid, substantial improvement in quality of life can be expected after THR surgery. Better physical function, sleep, emotional behavior, social interaction, and recreation are usually experienced in the first few months. At 2 years after surgery, patients who had undergone THR have reported greater satisfaction with their results than they had predicted in their best preoperative hypothetical scenarios.25

Clinical Case Review

1Anita had a minimally invasive THR. How will the rehabilitation process change because her procedure was less invasive?

Pain and swelling will be less because the trauma to soft tissue is less. The procedure is performed using a smaller opening. This may allow the patient to progress with bed mobility and transfers more quickly and with greater ease and comfort. The surgeon will determine weight-bearing status and rehabilitation progression. However, the hip precautions remain and the rehabilitation is usually similar (because the procedure is similar but performed with a smaller opening and in a smaller area). New materials such as metal-on-metal implants or ceramic implants are starting to be used. It is hoped that these prosthetic hips will have a longer life span.

2Sabrina had a noncemented THR surgery 3 days ago. She is TDWB with a walker but continues to place a moderate amount of weight on her affected LE. Because she has difficulty maintaining TDWB during gait, what can be done to help her?

A cracker can be taped to the sole of the patient’s forefoot. If the patient still has difficulty maintaining TDWB, then she should try using a thick-soled shoe only on the affected leg. If the patient is PWB, say 50%, then a scale can be used to give feedback regarding how it feels to bear 50% of the weight on the LE.

3Before having severe hip pain, Tracy was biking 20 to 30 miles a day, 4 days a week. She also competed in bicycle races and worked out in the gym with light weights three times a week. Should Tracy participate in a long-term exercise program after having a THR if it does not contradict the surgeon’s orders? Why?

Sheh and associates26 state that muscular weakness reduces the protection of the implant fixation surfaces during endurance activities. This may contribute to higher loosening rates reported in active patients. Therefore Tracy and other active patients should continue on a long-term exercise program to maintain good muscular strength around the hip.

4Karen is a 75-year-old female who had a THR 3 weeks ago. She is receiving physical therapy at home and has had two treatments. Today is her third treatment. Her main complaint is the swelling in her foot. Her last treatments emphasized mobility training. She lives with her daughter. She demonstrates stand by assist for most transfers; however, she requires minimal assistance for her affected LE when getting in and out of bed. What should be addressed during today’s treatment?

The patient was sitting upon arrival of the therapist. Physical therapy performed transfer training back to bed. When the patient was supine, the therapist massaged her foot and lower leg, milking the fluid up toward the heart. The therapist followed up with AROM for SLR with eccentric lowering of the LE using minimal assistance for guidance. In addition, active assistive hip abduction and adduction (before reaching midline and within the area of hip precautions) were done. Heel cord stretching was also addressed. A discussion regarding using a TED hose and maintaining LE elevation while sitting and in bed followed. In addition, the therapist encouraged the patient to do ankle pumps every hour throughout the day.

5Why is it not enough to quiz the patient about THR precautions?

Frequently, patients are able to recite the precautions correctly but they do not demonstrate their understanding of them through safe movement. They may still turn their bodies in a way that creates “relative” IR at the hip or flex their hips to greater than 90° while sitting down or standing up. Sitting surfaces often need to be raised up to be used safely. Many patients with NWB orders will put their foot on the ground while turning. Explain the difference between NWB and TDWB to the client as many times as necessary to change this behavior.

6Following her THR operation, Mary is concerned that her surgical cement may not adhere at the joint and asks if this will cause a dislocation of her prosthesis.

The THR surgery disrupts the integrity of the hip’s joint capsule. Movement beyond the limitations of the THR precautions places too much strain on the compromised joint capsule. This is the most frequent cause of postsurgical dislocation. Surgical cement is dry and at its full strength within 10 minutes of its application and is not a factor in dislocation although many patients worry about it. Knowledge of this can motivate the patient to adhere to his or her precautions and to the strengthening program.

7Why should the surgeon be consulted about the prescription of SLR exercises?

Enloe’s consensus group16 eliminated the SLR from their “ideal” THR rehabilitation plan, because Strickland and colleagues27 found that it created greater stresses than the amount incurred at the hip during normal unsupported gait. Lewis and Knortz15 found that SLRs should be initiated when the patient has regained partial or full weight bearing in the operative leg. Gilbert believes that SLRs are unnecessary and may cause dislocation; he warns therapists against using them.28

8Upon the physical therapist’s arrival at the patient’s home, the patient’s operative limb is found to be ruborous, warm, severely swollen, and very painful in spite of elevation and the use of ice. What needs to be done?

Be sure that the patient was discharged with the appropriate number of enoxaparin syringes and has followed through with these injections as prescribed. The patient may have a clot in his leg. Check the status of the surgical scar. There is the possibility of an infection. Make sure that the patient has taken any antibiotics prescribed since other causes of infection may be due to dental work or other medical procedures unrelated to the THR. Refer the patient back to the surgeon for further evaluation.

9Robert is having difficulty with transferring into and out of his car safely. What adjustments can help him?

A clean plastic trash bag placed over the passenger’s seat provides a slippery surface, which allows the patient to glide-pivot around on the passenger’s seat and assume the rider’s position more easily. If the height of the seat is adjustable, then raise the seat to the highest possible position. The back of the seat may need to be tilted backward to maintain the precaution of less than 90° flexion at the hip.

10John was running 3 to 5 miles a day before hip pain necessitated a THR surgery. Should he resume running at the end of his rehab phase?

Running is not recommended following a THR surgery. Alternatives for John could include speed walking, the treadmill, stair climber, and the elliptical cross-trainer. John should be set up with a stretching program that will allow him to pursue his activities showing good posture. This could help to avoid the uneven wear and tear on joints that can encourage further deterioration.

11What advice can be given when the patient asks about sexual activity following a THR?

Sexual activity after an uncomplicated THR may resume in approximately 1 to 2 months with the surgeon’s approval. Studies have shown that most patients feel uncomfortable asking for this type of information. Women tend to prefer the supine position or side lying on the nonoperated side. Men prefer the supine position. The patient is advised to take the more passive role and the prone position may be resumed in 2 to 3 months after surgery.9