CHAPTER 54 Total Facet Replacement

Facet Anatomy and Function

The lumbar facet joints have been thoroughly studied. Much is known about their loading, biomechanical function, time-related anatomic changes, tropism and asymmetry, modes of articular wear, and soft tissue attachments.1–35

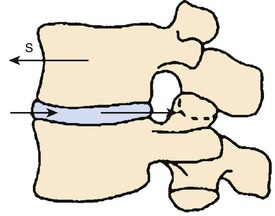

At its most narrow analysis, the facet joint is designed to function as a shear stop—an anterior shear stop (Fig. 54–1). Facet joints prevent anterior shear forces from destroying the disc, which is primarily designed to absorb compressive loads. The disc is so well designed for its purpose that it is essentially impossible to injure the anulus with purely compressive loads.26 Also, the facets control varying amounts of rotation and limit flexion of the lumbar spine,28–3136 but their most important function is to protect the disc from parallel force vectors.

Viewed in this simplified manner, it becomes clearer why degeneration of these lumbar apophyseal joints produces so much spinal pathology. The loss of even 1 mm of cartilage thickness within the facet joint allows a significant increase in anterior-posterior translational motion to occur. This increased motion causes repeated strain of the multifidus muscle and facet capsule ligaments, increases the shear load on the disc and the posterior and anterior longitudinal ligaments, and allows the neural foramen and lateral recess to collapse with flexion and extension of the spine. At the same time, cartilage wear stimulates spur formation in all directions around the facet joint, as cartilage wear typically does in all degenerative synovial joints. These osteophytes encroach further on the neural elements increasing central and lateral stenosis, and the osteophytes may act as a source of pain when they impinge on each other or the pars interarticularis. Degeneration can continue until facet subluxation occurs, producing further stenosis (Fig. 54–2).

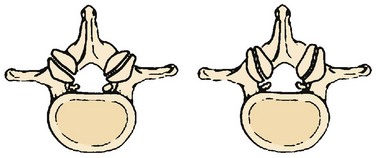

Concomitant with the five degenerative changes in the apophyseal joints—loss of articular cartilage, spur formation, loss of control of anterior shear forces, facet subluxation, and increased anterior-posterior translation—the facets also frequently undergo disadvantageous morphologic changes with aging. These changes undermine the ability of the spine to withstand shear forces. In infant spines, the facets are primarily coronally oriented.25 In adult spines, the lumbar facets generally have a small anteromedial coronal component and a large posterior sagittal component (Fig. 54–3). As the spine ages, the facet becomes more and more sagittally aligned with a smaller and smaller coronal component (Fig. 54–4). The coronal part of the facet joint controls shear forces.28 In a presentation at the International Spinal Arthroplasty Society Meeting in Montpelier, France in 2002, DuPont, using finite element analysis, verified how the shear forces across the disc increase as the facets are directed more and more sagittally.

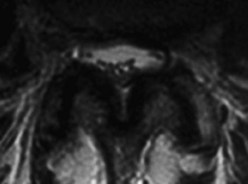

FIGURE 54–4 Sagittally aligned, asymmetric, and dislocated facet joints at L4-5 in a 56-year-old patient.

There is at least one additional force working on the lumbar facet joint. Depending on the position of the spine, the facets absorb 0% (in full flexion) to 33% (in full extension) of the compressive (axial) load at a given level.23,37 An incompetent, degenerative facet joint can no longer absorb its share of the compressive loads, which can narrow the neural foramen further in an up-down direction, especially with the spine in extension.

Radiologic Diagnosis and Issues

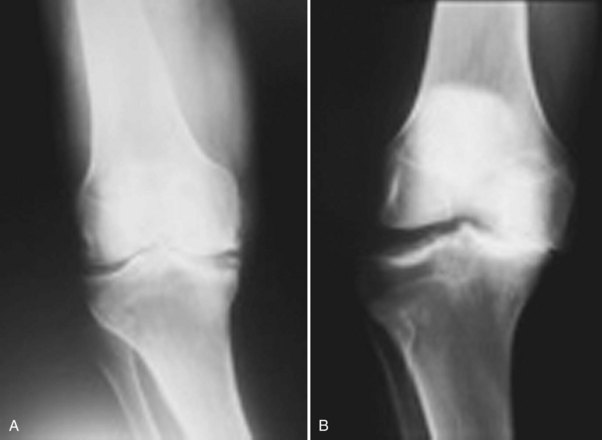

Although excellent radiologic tools have been developed, including computed tomography (CT), CT myelogram, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), they may not be used to their fullest advantage. There is no spinal equivalent to the 30-degree weight-bearing anteroposterior view of the knee (Fig. 54–5) to detect cartilage wear or joint laxity. Similar positional views of other joints of the extremities, such as weight-bearing anteroposterior and lateral views of the feet and the 30-degree angle view of the shoulder, have been developed to aid in diagnosing arthritis and instability but not as well with advanced imaging for the spine.

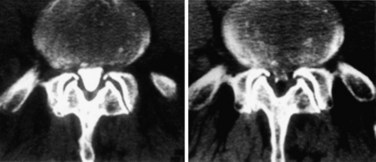

A vest with pantaloons has been developed that can individually manipulate vertebral bodies to obtain much more information on a segmental level, but this is under development, and weight-bearing extension views of the lumbar spine probably will not be ready for initial usage before 2012. Other investigators have developed CT scan techniques to show positional lateral recess stenosis (Fig. 54–6).

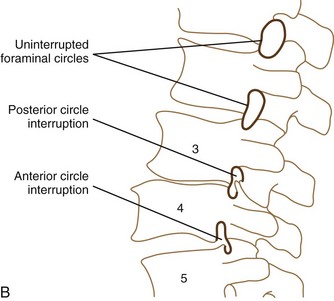

In the same vein, the inferior arc of the pedicle should follow the posterior aspect of the superior and inferior vertebral bodies associated in its foraminal opening, along with the inferior articular process and the arc of the superior articular process. If this circle is unbroken (i.e., the line is smooth) (Fig. 54–7), the foraminal space, at least in a static film, is probably adequate from a bony standpoint. If the proximal end of the superior articular facet or the superior spurs of the inferior articular surface intrude into the hemicircle formed by the pedicle and the inferior facet, the broken foraminal line would indicate facet joint degeneration and possibly suggest instability. This line can be assessed on flexion and extension films and is a more subtle sign than measuring the number of millimeters of spondylolisthesis. An additional sign within the foramen to aid in diagnosis could be the intrusion sign of the superior endplate into the intervertebral foramen. Figure 54–7 illustrates both abnormalities, the former at L3-4 and the latter at L4-5.

Current Treatment of Posterior Lumbar Degeneration

All of these operations have their successes and their failures with quite a bit of variability as reported in the literature. Wide decompressive laminectomy has been shown to have 57% to 85% good results at 4 years.38–41 Postoperative problems and complications include segmental instability, recurrent spinal stenosis, continued back pain, infection, neural injury, and dural tears.35,42

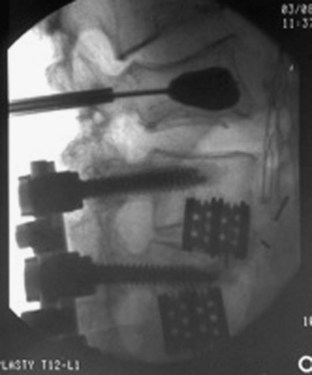

Decompression and arthrodesis are the mainstays of treatment for degenerative facets. Numerous fusion techniques and associated implantable instrumentation are available, and the operation has improved to the point where a successful radiographic fusion is the rule. As Vaccaro and Ball42 have written, “Though the majority of studies have shown that the radiographic fusion success rate is improved with the addition of internal fixation, the benefits in the majority of degenerative spinal disorders are unclear in terms of patient function.” Some of the complications from combined decompression and fusion include 3% to 6% infection rate,43 continued pain, juxtasegmental instability or fracture (Fig. 54–8), failed fusion, and failed hardware.

Clinical Testing

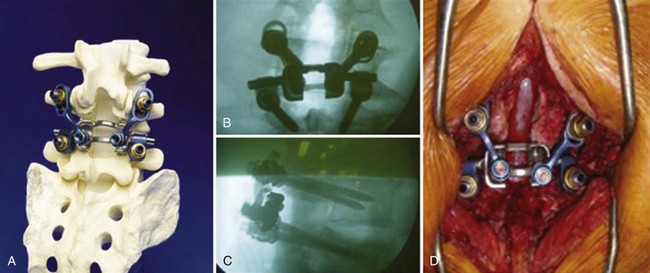

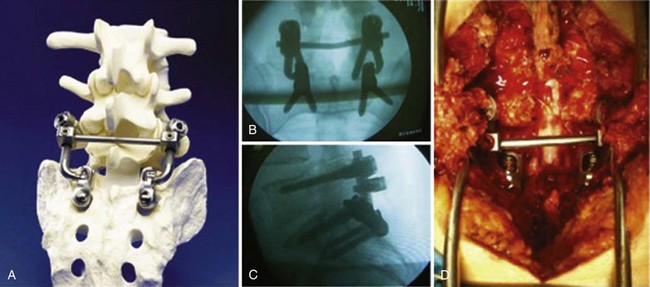

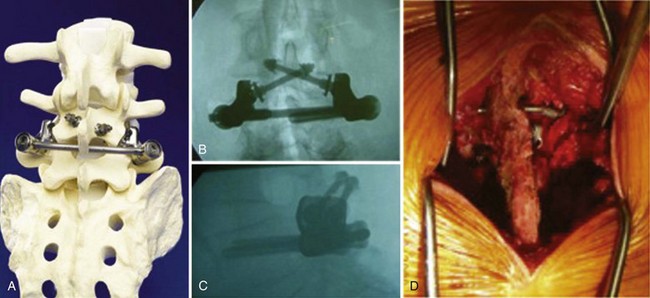

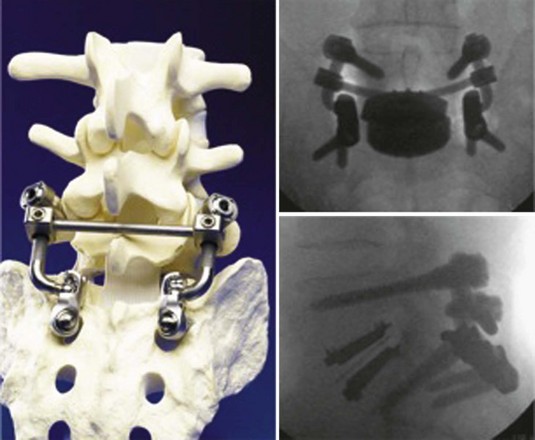

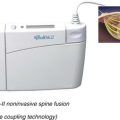

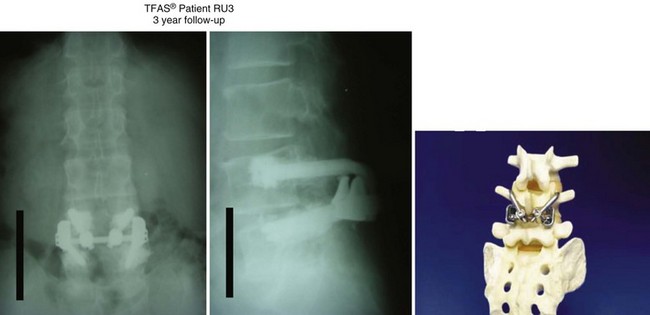

Greater than 200 patients have been surgically treated worldwide with total facet replacement with follow-up in some cases of more than 3 years. With the exception of a few patients who were unsuitable to receive the implant (extreme obesity), there have been no reported incidents of breakage or dislocation. Pain relief has been excellent (see later). This operation has found some acceptance by spine surgeons, but most are waiting for more data to be produced in formal studies before making a decision about posterior spinal arthroplasty. The total facet replacement family of products includes four different types of total facet implants: a cemented total facet replacement for older or osteoporotic patients (Fig. 54–9), an uncemented total facet replacement for younger patients with normal or nonosteoporotic bone (Fig. 54–10), a lumbosacral total facet arthroplasty designed for the L5-S1 facet joint, and a translaminar facet replacement implant that is targeted for minimally invasive approaches and can be used to treat single-level and multilevel syndromes. The first three types are pedicle-based. The translaminar designs can work across a patient’s natural disc or in conjunction with a total disc replacement and for multilevel stenosis (Figs. 54-11 and 54-12), assuming the laminae are left intact.

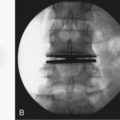

FIGURE 54–9 Cemented facet replacement (cemented total facet arthroplasty system) shown is 3 years postoperative.

Clinical Results of Total Facet Arthroplasty System (Cemented Facet Replacement)

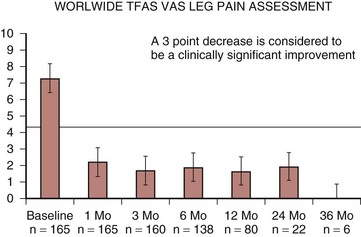

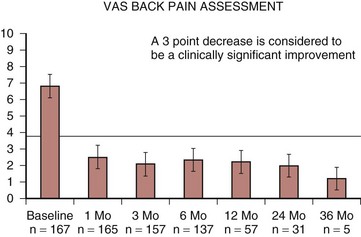

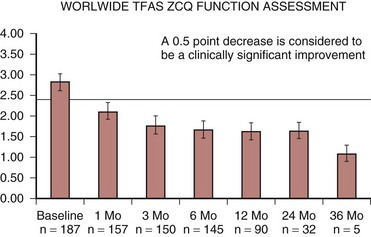

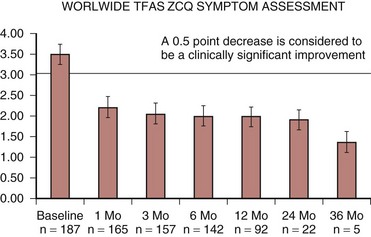

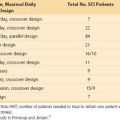

Several scales were used to evaluate the clinical results of the total facet arthroplasty system prosthesis placed in 180 patients, including the visual analog scale (VAS) leg pain assessment, VAS back pain assessment, and Zurich Claudication Questionnaire (ZCQ) symptom assessment. The results of these studies are presented in Figures 54-13 through 54-16. The results of all three pain scales showed a profound decrease in pain at 1 month postoperatively, and the pain continued to lessen in subsequent follow-up assessments at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months. Likewise, the ZCQ functional scores continued to improve over the same period. Comparative results in control patients receiving decompression and fusion are being collated at this time.

Future of Total Facet Replacement

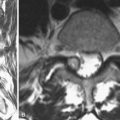

There is evidence from multiple national and international presentations that total disc replacement accelerates facet pathology. Patients with previously implanted artificial discs that have subsequently developed posterior stenosis or facet-related pathologies have been well treated with facet replacement. An ongoing FDA IDE study is about 2 years from completion. In addition, patients with combined anterior and posterior pathology may be successfully treated with complete segmental replacement as shown in Figure 54–17—with a total disc and bilateral face replacements, rather than fusions, in selected cases.

Pearls

Pitfalls

Key Points

1 Fujiwara A, Lim TH, Howard S, et al. The effect of disc degeneration and facet joint osteoarthritis on the segmental flexibility of the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3036-3043.

2 Scoles PV, Linton AE, Latimer B, et al. Vertebral body and posterior element morphology: The normal spine in middle life. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988;13:1082-1086.

3 Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Larson MG, et al. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:809-816.

4 Spengler DM. Degenerative stenosis of the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:82-86.

5 Vaccaro AR, Ball ST. Indications for instrumentation in degenerative lumbar spinal disorders. Orthopedics. 2000;23:260-271.

6 Wright T, Goodman S. Implant wear. In: Total Joint Replacement: Clinical and Biologic Issues, Material and Design Considerations. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgery; 2001.

1 Adams MA, Hutton WC. The mechanical function of the lumbar apophyseal joints. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8:327-330.

2 Adams MA, Hutton WC, Scott JR. The resistance to flexion of the lumbar intervertebral joint. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1980;5:245-253.

3 Adams MA, McNally DS, Dolan P. “Stress” distributions inside intervertebral discs: The effects of age and degeneration. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:965-972.

4 Badgley C. The articular facets in relation to low back pain and sciatic radiation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1941;23:481-496.

5 Berlemann U, Jeszenszky DJ, Buhler DW, et al. Facet joint remodeling in generative spondylolisthesis: An investigation of joint orientation and tropism. Eur Spine J. 1998;7:376-380.

6 Boden SD, Martin C, Rudolph R, et al. Increase of motion between lumbar vertebrae after excision of the capsule and cartilage of the facets: A cadaver study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:1847-1853.

7 Butler D, Tratimow JH, Anderson GB, et al. Discs degenerate before facets. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15:111-131.

8 Farfan HF, Cossette JW, Robertson HG, et al. The effects of torsion on the lumbar intervertebral joints: The role of torsion in the production of disc degeneration. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:468-497.

9 Farfan HF, Huberdeau RM, Dubow HF. Lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration: A postmortem study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:492-510.

10 Farfan HF. Mechanical Disorders of the Low Back. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1973.

11 Fujiwara A, Lim TH, Howard S, et al. The effect of disc degeneration and facet joint osteoarthritis on the segmental flexibility of the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3036-3043.

12 Grogan J, Nowicki BH, Schmidt TA, et al. Lumbar facet joint tropism does not accelerate degeneration of the facet joints. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1325-1329.

13 Herno A, Airaksinen O, Saari T. Long term results of surgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;18:1471-1474.

14 Hickey RF, Tregonning GD. Denervation of spinal facet joints for treatment of chronic low back pain. N Z Med J. 1977;85:96-99.

15 Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Farfan HF. Instability of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop. 1982;110:23.

16 Koeller W, Muchlhaus S, Meier W, et al. Biomechanical properties of human intervertebral discs subjected to axial dynamic compression—influence of age and degeneration. J Biomech. 1986;19:807-816.

17 Lewin T. Osteoarthritis in lumbar synovial joints: A morphological study. Acta Orthop Scand. 1964;73:1-112.

18 Lorenz M, Patwardhan A, Vanderby RJr. Load-bearing characteristics of lumbar facets in normal and surgically altered spinal segments. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8:122-129.

19 Malmivaara A, Videman T, Kuosma E, et al. Facet joint orientation, facet and costovertebral joint osteoarthrosis, disc degeneration, vertebral body osteophytosis, and Schmorl’s nodes in the thoracolumbar junctional region of cadaveric spines. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987;12:458-463.

20 Mooney V, Robertson J. The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:149-156.

21 Panjabi MM, Oxland T, Takata K, et al. Articular facets of the human spine: Quantitative three-dimensional anatomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;18:1298-1310.

22 Panjabi MM, Oxland TR, Yamamoto I, et al. Mechanical behavior of the human lumbar and lumbosacral spine as shown by three-dimensional load-displacement curves. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:413-424.

23 Panjabi MM, Yamamoto I, Oxland TR, et al. How does posture affect coupling in the lumbar spine? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989;14:1002-1011.

24 Reichmann S. The postnatal development of form and orientation of the lumbar intervertebral joint surfaces. Z Anat Entwicklung. 1971;133:102-103.

25 Scoles PV, Linton AE, Latimer B, et al. Vertebral body and posterior element morphology: The normal spine in middle life. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988;13:1082-1086.

26 Sheaby CN. Facet denervation in the management of back and sciatic pain. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:157-164.

27 Simkin PA, Graney DO, Feichtner JJ. Roman arches, human joints and disease: Differences between convex and concave sides of joints. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:1308-1311.

28 Taylor JR, Twomey LT. Age changes in lumbar zygapophyseal joints: Observations on structure and function. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1986;11:739-745.

29 Taylor JR, Twomey LT. Sagittal and horizontal plane movement of the human lumbar vertebral column in cadavers and in the living. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1980;19:223-232.

30 Twomey LT, Taylor JR. Sagittal movements of the human lumbar vertebral column: A quantitative study of the role of the posterior vertebral elements. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983;64:322-325.

31 Twomey L, Taylor J, Furniss B. Age changes in the bone density and structure of the lumbar vertebral column. J Anat. 1983;136:15-25.

32 Twomey LT, Taylor JR. Age changes in the lumbar articular triad. Aust J Physiother. 1984;31:106-112.

33 White AA, Panjabi MM. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1978.

34 Wright T, Goodman S. Implant wear. In: Total Joint Replacement: Clinical and Biologic Issues, Material and Design Considerations. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgery; 2001.

35 Yuan HA, Garfin SR, Dickman CA, et al. A historic cohort study of pedicle screw fixation in thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal fusions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(Suppl 20):2279S-2296S.

36 Shirazi-adl SA, Shrivastava SC, Ahmed AM. Stress analysis of the lumbar disc-body unit in compression: A three-dimensional nonlinear finite element study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1984;9:2.

37 Lin HS, Liu YK, Adams KH. Mechanical response of the lumbar intervertebral joint under physiologic (complex) loading. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:41-55.

38 Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Brick GW, et al. Clinical correlates of patient satisfaction after laminectomy for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:1155-1160.

39 Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Larson MG, et al. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:809-816.

40 Lipson SJ. Spinal stenosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1988;14:613-618.

41 Spengler DM. Degenerative stenosis of the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:82-86.

42 Vaccaro AR, Ball ST. Indications for instrumentation in degenerative lumbar spinal disorders. Orthopedics. 2000;23:260-271.

43 Wang JC, Bohlman HH, Riew KD, et al. Dural tears secondary to operations on the lumbar spine: Management and results after a two-year-minimum follow-up of eighty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1728-1732.

times body weight with 10 million cycles and found to withstand that repetitive loading and motion successfully. The new facet joint is typically pointed almost straight posterior with a 17-degree incline to limit flexion to physiologic levels. Motion studies have shown that the replaced facet approximates well the motion of the normal joint. Of the four types of facet joints clinically anatomically required for the spine (see later), all required a cross bar for adequate strength except for a translaminar device used for patients with multilevel disease or who have a preexisting total disc replacement.

times body weight with 10 million cycles and found to withstand that repetitive loading and motion successfully. The new facet joint is typically pointed almost straight posterior with a 17-degree incline to limit flexion to physiologic levels. Motion studies have shown that the replaced facet approximates well the motion of the normal joint. Of the four types of facet joints clinically anatomically required for the spine (see later), all required a cross bar for adequate strength except for a translaminar device used for patients with multilevel disease or who have a preexisting total disc replacement.