CHAPTER 15 Total extraperitoneal (TEP) hernia repair

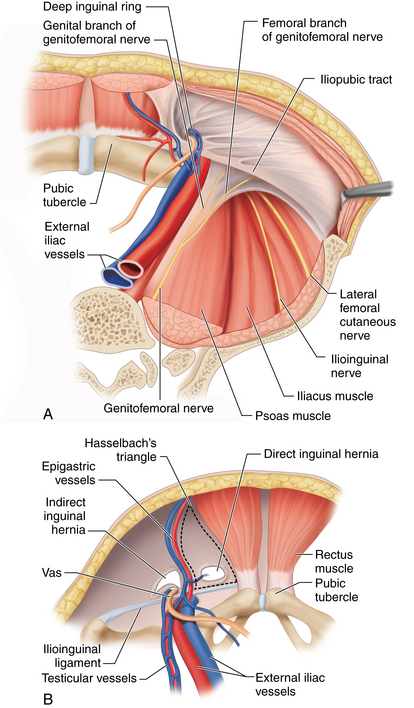

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

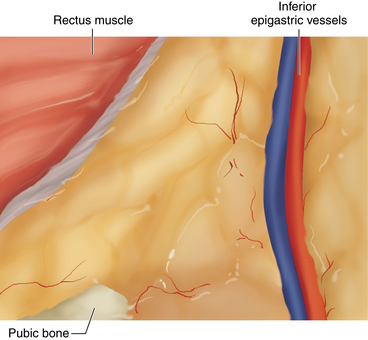

♦ A thorough knowledge of the extraperitoneal inguinal anatomy is required to avoid complications. The most important first step for successful completion of total extraperitoneal (TEP) hernia repair is correct entry into the preperitoneal space. Upon dissection of the preperitoneal space, proper orientation is confirmed by visualizing the rectus abdominis muscles superiorly, the preperitoneal fat and peritoneum inferiorly, the pubic symphysis and Cooper’s ligament in the midline, and the inferior epigastric vessels laterally (Figure 15-1).

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

Patient selection

♦ Relative to standard open inguinal herniorrhaphy, the laparoscopic approach provides superb laparoscopic visualization of the inguinal anatomy with magnified views, with the added benefit of being able to evaluate and repair the contralateral side without the need for additional incisions. Relative to open hernia repair, the laparoscopic approach is associated with improved cosmesis, reduced postoperative pain, faster recovery and return to work, and similar complication and recurrence rates. In the setting of a recurrent inguinal hernia following previous open repair, a laparoscopic repair is the preferred approach. Not only does it avoid dissection through old scar, but it is associated with reduced postoperative and recovery time and similar or improved recurrence rates compared with reoperative open herniorrhaphy.

♦ Laparoscopic repair can be performed either transabdominally (TAPP) or totally extraperitoneally (TEP); the choice largely depends on the surgeon’s experience and preference.

♦ Relative to TAPP, TEP, which is performed without violating the peritoneal space, may reduce the incidence of postoperative adhesions.

♦ Absolute contraindications to laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair include any medical condition that precludes general anesthesia, such as severe cardiac or pulmonary disease. Other contraindications include incarcerated and potentially strangulated hernia. Relative contraindications include previous prostatic surgery, which will distort anatomic planes. In addition, TEP repair may complicate future prostatic surgery, which should be a consideration for older male patients.

Preoperative preparation and anesthetic considerations

♦ Patients are instructed to void just prior to the procedure to minimize the use of urinary catheters. The combination of excessive intraoperative fluids and bladder catherization can be associated with an increased incidence of urinary retention. DVT prophylaxis is not required unless the patient is at risk for thromboembolism.

♦ Following general endotracheal anesthesia and muscle paralysis, the abdomen is shaved, prepped with antiseptic solution, and draped using a Steri-Drape. Prophylactic antibiotics are administered intravenously. First-generation cephalosporin or vancomycin in penicillin-allergic patients is typically given preoperatively. Patients are placed supine on the table with arms either positioned to the sides or tucked.

Surgical equipment

♦ Laparoscopic instrumentation includes a 30-degree, 10-mm laparoscopic camera; two 5-mm trocars; two blunt graspers; a 5-mm laparoscopic tacker; and one or two 6-by-6-inch pieces of polypropylene mesh.

♦ We prefer using a 10-mm dilating trocar for dissection, as opposed to blunt dissection, and a 10-mm structural trocar with pump for balloon inflation.

Step 3. Operative steps

Entry and dissection of the preperitoneal space

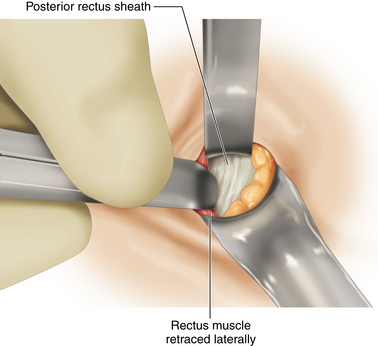

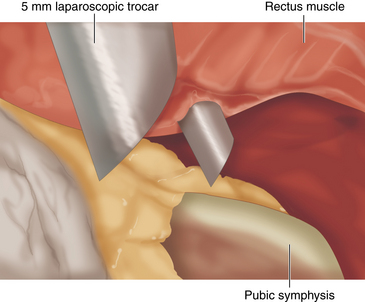

♦ A 2- to 3-cm transverse incision is made with a skin knife just lateral and below the umbilicus on the side opposite the symptomatic hernia. This incision avoids the midline where the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths merge. This incision is carried down through the subcutaneous tissues down to the anterior rectus sheath, which is incised with a 15-mm blade, just enough to expose the underlying rectus muscle. This incision is extended on either side with Metzenbaum scissors. The curved Mayo scissors are used to retract the rectus muscle laterally to expose the underlying posterior sheath (Figure 15-2).

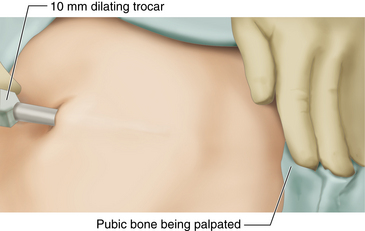

♦ The surgeon carefully inserts the 10-mm dilating trocar in the space underneath the rectus muscle on top of the posterior rectus sheath and advances it inferiorly toward the pubic symphysis, making sure to stay away from the midline and maintaining downward traction on the trocar to avoid accidental posterior entry into the peritoneal cavity or bladder injury. The trocar is advanced inferiorly until it reaches the pubic bone in the midline (Figure 15-3).

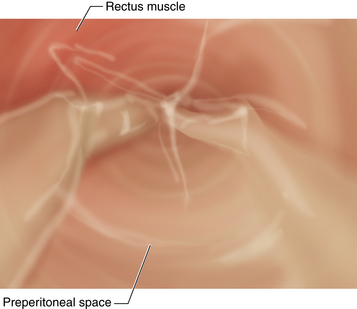

♦ The laparoscope is introduced through the trocar, and the balloon is inflated using 40 squeezes of the pump, which instills approximately 1 liter of air. Balloon insufflation of the preperitoneal space is performed under laparoscopic visualization to ensure that the proper plane has been entered (Figure 15-4).

♦ An alternative for preperitoneal dissection is blunt rather than balloon dissection. The preperitoneal space can be dissected using the laparoscope itself by sweeping it side to side and then placing a standard 10-mm Hassan trocar through the subumbilical incision.

♦ If proper entry into the preperitoneal space has been achieved, several anatomic landmarks can usually be visualized, including the pubic symphysis in the midline, the rectus muscles anteriorly, and the inferior epigastric vessels laterally (Figure 15-5).

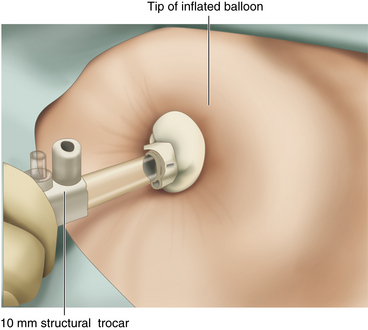

♦ Following balloon dissection of the preperitoneal space, the balloon is deflated, and the dilating trocar is removed and replaced with the shorter 10-mm structural trocar. The balloon at the tip of the structural trocar is inflated with four squeezes of the pump, and the trocar is locked into position and connected to carbon dioxide, which is insufflated to a pressure of 9 mmHg (Figure 15-6).

♦ The laparoscope is introduced through the 10-mm structural trocar, and two 5-mm trocars are inserted under laparoscopic visualization, one above the pubic symphysis and the other halfway between the subumbilical and suprapubic ports (Figure 15-7).

Identification of anatomic landmarks

♦ The next step is identification and clearance of the pubic symphysis and Cooper’s ligament, which usually requires light blunt dissection of the areolar tissue still obscuring them.

♦ Using the blunt graspers and following the principles of traction and countertraction, the preperitoneal tissues are bluntly mobilized off the anterior abdominal wall to open up the preperitoneal space further. If not already visualized during balloon dissection, the inferior epigastric vessels should be identified early to avoid inadvertent injury during dissection and to help identify direct and indirect defects.

♦ Care must be taken to avoid aggressive dissection in the retropubic space and lateral and inferior to Cooper’s ligament where the femoral space and iliac vessels are located.

Clearance of the lateral space

♦ The next step consists in the clearance of the lateral space both to complete dissection of the preperitoneal space as well as to prepare for lateral mesh placement. This is performed by bluntly pulling the peritoneum reflection inferiorly, which can usually be visualized as a white edge of peritoneum, and away from the anterior abdominal wall all the way toward the anterior superior iliac spine.

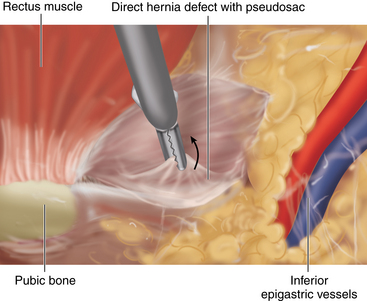

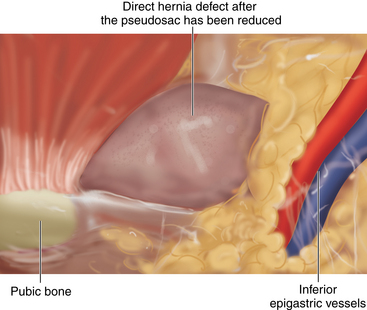

Identification of a direct defect

♦ During balloon or blunt dissection of the preperitoneal space, if present, a direct hernia is usually reduced. A direct defect can be found just medial to the superficial epigastric vessels, which may be associated with a “pseudosac.” This pseudosac, which looks like peritoneum, represents posterior protrusion of the transversalis fascia and needs to be bluntly dissected off preperitoneal fat until it retracts back through the direct defect (Figures 15-8 and 15-9).

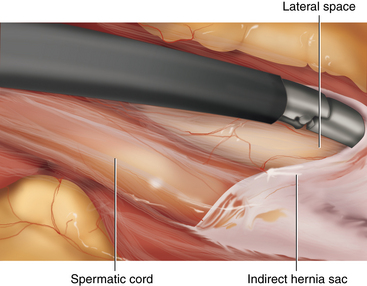

Identification of an indirect defect

♦ The spermatic cord and round ligament are found just lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels and need to be carefully dissected to identify an indirect sac or lipoma of the cord.

♦ When identified, the sac or lipoma needs to be reduced out of the ring if a scrotal component of the hernia exists. The sac is dissected off the cord structures or round ligament and pulled back, well below the spermatic cord and round ligament (Figure 15-10).

♦ In a man, the dissection is considered complete when the sac is free where the vas and cord structures separate.

♦ Care must be taken to avoid making a hole in the sac during this dissection, which could result in pneumoperitoneum and significant loss of working space. In this event, the defect in the peritoneum can be closed using an Endoloop. Alternatively, a Veress needle can be inserted into the abdominal cavity to evacuate the pneumoperitoneum.

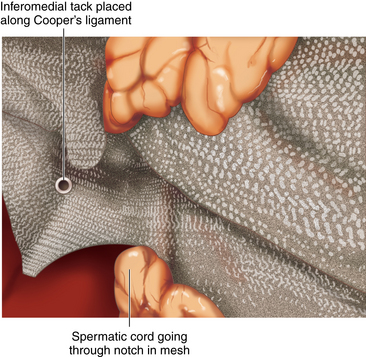

Placement of the mesh

♦ A 6-by-6-inch piece of polypropylene mesh is trimmed to 4 by 6 inches. The medial lower corner is cut obliquely to mark the level where the mesh should lie medially over Cooper’s ligament. Just distal to the oblique cut, a notch is made through the mesh to accommodate the spermatic cord around the mesh.

♦ The mesh is then rolled tightly from medial to lateral, inserted through the structural trocar, and pushed in position using the laparoscope. It is then carefully unrolled and positioned to cover the inguinal floor.

♦ Care should be taken to ensure that the peritoneum and sac (when present) remain below the mesh. The mesh should be positioned such that it covers the direct, indirect, and femoral spaces with good overlap (Figure 15-11).

♦ Once properly positioned, tacks are placed to secure the mesh into position. Typically, a total of three to five tacks are placed: one at the pubic tubercle, another one just distal along Cooper’s ligament, and one to three tacks just superior to the pubic tubercle onto the anterior abdominal wall. The lateral component of the mesh is held in place easily by the peritoneum as the carbon dioxide is released.

♦ To avoid injury to the ilioinguinal or genitofemoral nerves, care is taken to avoid placing tacks lateral to the epigastric vessels.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ Accidental entry into the peritoneal cavity is not by itself an indication to convert the procedure to open repair. The surgeon has several alternatives. One alternative is to reattempt entry into the proper space through that same incision. Another is to make a second incision on the opposite side of the umbilicus and go through the same steps to enter the preperitoneal plane. If both approaches fail, conversion to TAPP or open repair is indicated.

♦ One important technical point to avoid nerve injury is the avoidance of monopolar cautery and the use of bipolar cautery only medial to the epigastric vessels if and when used. Similarly, tacks should only be placed medial to the epigastric vessels.

Arregui ME, Davis CJ, Yucel O, et al. Laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia using a preperitoneal approach: a preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;2;1:53-58.

Bringman S, Haglind E, Heikkinen T, et al. Is a balloon dissection beneficial in totally extraperitoneal hernioplasty (TEP). Surg Laparosc Endosc. 2001;15(5):322-326.

Johansson B, Hallerback B, Glise H, et al. Laparoscopic mesh versus open preperitoneal mesh versus conventional technique for inguinal hernia repair: a randomized multicenter trial (SCUR Hernia Repair Study). Ann Surg. 1999;230;2:225-231.

Kieturakis MJ, Nguyen DT, Vargas H, et al. Balloon dissection facilitated laparoscopic extraperitoneal hernioplasty. Am J Surg. 1994;168(6):603-607.

McKernan JB, Laws HL. Laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia using a preperitoneal prosthetic approach. Surg Endosc. 1993;7(1):26-28.

Takata MC, Duh QY. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Surg Clin N Am. 2008;88(1):157-178.

Wake BL, McCormack K, Fraser C, et al. Transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) vs totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2005. CD004703