10 Topical neurotoxin

Summary and Key Features

• Injectable BoNT-A has been successfully used across a range of medical disorders including strabismus, blepharospasm, focal dystonia, migraine, spasticity associated with juvenile cerebral palsy and adult stroke as well as various cosmetic treatments such as to temporarily relax hyperfunctional rhytides.

• Alternative methods have been developed due to limitations and disadvantages of injections of BoNTA which includes iontophoresis device-based approaches and topical liposomes and CPP drug delivery systems.

• Topical botulinum toxin delivery through the skin may offer opportunities to treat anatomical areas that are either difficult to manage with injectables or where patients may prefer to avoid injectables, and there may also be useful roles for topical botulinum therapies as adjunctive or extender therapies for the injectable techniques now in use.

Background

While aesthetic medicine has been inundated with treatments for facial rhytides, BoNT-A is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved treatment to temporarily relax hyperfunctional rhytides. Since 1992, botulinum toxin has been used to treat a variety of cosmetic conditions and medical indications. Following the first description of the treatment for glabellar rhytides (‘frown line’ wrinkles) by Carruthers & Carruthers in 1992, botulinum toxin has revolutionized the practice of aesthetic medicine. In 2002, the United States (US) FDA approved the use of Botox® Cosmetic (botulinum toxin type A purified toxin complex; Allergan, Inc.) for the treatment of moderate-to-severe glabellar rhytides, associated with corrugator and / or procerus muscle activity in adult patients 65 years of age and younger. In 2004, Carruthers et al reported the consensus recommendations that BoNT-A is effective and safe, and patient satisfaction is high. By 2005, Botox® cosmetic injections were the most common non-invasive physician-administered cosmetic procedure worldwide.

Need for transcutaneous delivery systems

Matarasso & Matarasso reported in 2001 that the paralytic effect of injected BoNT-A can span up to 3 cm from the site of injection and even further when dilute concentrations and large volumes of BoNT-A are used. Limitations of injections of BoNT-A include pain, erythema, swelling, potential infection from needle use, and potential for reduced normal expression in the treated area. The patient’s pre-treatment medical regimen is potentially impacted by being advised to avoid aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and vitamin E prior to injection, to reduce the risk of bleeding and bruising. Bruising is of particular concern in the crow’s feet (also known as lateral canthal lines or LCL), where the blood vessels are superficial and the skin is thin. Because of the disadvantage of requiring injection as the route of administration, alternative methods of drug delivery have been developed that can address some of these concerns.

Potential approaches to transcutaneous delivery of BoNT-A

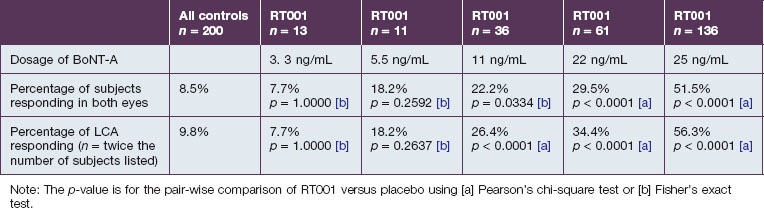

Based upon the initial reports of RT001 by Glogau and Brandt et al, as well as prior unpublished work, a full Phase II clinical program for the temporary improvement in the appearance of moderate to severe lateral canthal lines was completed including over 550 subjects exposed to RT001. Dose escalation studies were undertaken across five studies for RT001 in LCL. These studies (1) encompassed all experiences with the proposed Phase III dose of peptide excipient, (2) employed similar efficacy scales, enrollment criteria, formulation, timepoints, and consistency of treatment effect, and (3) reflected planned Phase III studies. All studies that were similar have been included in this analysis. Escalating doses of RT001 from 5.5 to 25 ng/mL of BoNT-A led to an increasing proportion of responders based on 2-point or greater improvement on a validated investigator global assessment of lateral canthal line severity (IGA-LCL scale) whether viewed by individual lateral canthal area (LCA) per protocol or subject (both eyes responding as proposed for Phase III studies) as detailed in Table 10.1. An example is shown in Figure 10.1.

Table 10.1 Response rates by 2 points or greater improvement on IGA-LCL 4 weeks after treatment with RT001

Figure 10.1 A representative 2-point mover in the Phase II trials: (A) baseline; (B) 4 weeks post-treatment.

Reproduced with permission of Revance Therapeutics, Inc.

After dosage selection, efficacy of the proposed Phase III dose of RT001 was demonstrated in two confirmatory Phase II studies by Glogau et al. In these studies RT001 Topical Gel demonstrated efficacy following a 30-minute application in comparison with controls for the treatment of subjects with moderate to severe lateral canthal lines related to orbicularis oculi muscle spasm, as summarized in Table 10.2. End points employed both investigators’ assessments (IGA-LCL) and subject assessments (PSA) of lateral canthal line severity as well as composites of both measures. Additionally subject self-perception of improvement was tabulated. The 25 ng/mL dose of RT001 demonstrated statistically significant efficacy versus placebo on the primary composite endpoint as well as all secondary endpoints and was well tolerated.

Table 10.2 Efficacy analyses for the proposed Phase III dose of RT001

| RT001 subjects (25 ng) | Control subjects | |

|---|---|---|

| Subjects assessed at week 4 (N) | 136 | 132 |

| Composite ≥2-point improvement in PSA and ≥2-point IGA-LCL improvement in both LCA | 41.9% p < 0.0001 |

0.74% |

| ≥2-Point IGA-LCL improvement in both LCA | 51.5% p < 0.0001 |

10.6% |

| ≥2-Point improvement in PSA | 46.3% p < 0.0001 |

3.0% |

| ≥1-Point IGA-LCL improvement in both LCA | 75.7% p < 0.0001 |

22.0% |

| PGIC improved or much improved | 52.9% p < 0.0001 |

7.6% |

Note: The p-value is from the Pearson’s chi-square test.

American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank. statistics. Online. Available www.surgery.org/download/2006stats.pdf, 2006. 30 March 2007

Brandt F, O’Connell C, Cazzaniga A, et al. Efficacy and safety evaluation of a novel botulinum toxin topical gel for the treatment of moderate to severe lateral canthal lines. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(suppl 4):2111–2118.

Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Botulinum toxin type A. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2005;53:284–290.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Treatment of glabellar frown lines with C. botulinum-A exotoxin. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1992;18:17–21.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. The evolution of botulinum toxin type A for cosmetic applications. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2007;9:186–192.

Carruthers J, Fagien S, Matarasso SL, et al. Consensus recommendations on the use of botulinum toxin type A in facial aesthetics. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;114:S1–S22.

Chajchir I, Modi P, Chajchir A. Novel topical BoNTA (CosmeTox, Toxin Type A) cream used to treat hyperfunctional wrinkles of the face, mouth, and neck. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2008;32:715–722.

Fittipaldi A, Ferrari A, Zoppé M, et al. Cell membrane lipid rafts mediate caveolar endocytosis of HIV-1 Tat fusion proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(36):34141–34149.

Glogau RG. Topically applied botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis: results of a randomized, blinded, vehicle-controlled study. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:S76–S80.

Glogau RG. Botulinum toxins in dermatology: cosmetic and clinical applications. In: Cohen JoelL, ed. Botulinum toxins in dermatology: cosmetic and clinical applications. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

Glogau RG, Blitzer A, Brandt F, et al. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a botulinum toxin type A topical gel for the treatment of moderate to severe lateral canthal lines. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2012;11(1):38–45.

Hallett M. One man’s poison–clinical applications of botulinum toxin. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341:118–120.

Kaplan IM, Wadia JS, Dowdy SF. Cationic TAT peptide transduction domain enters cells by macropinocytosis. Journal of Controlled Release. 2005;102(1):247–253.

Kavanagh GM, Oh C, Shams K. BOTOX delivery by iontophoresis. British Journal of Dermatology. 2004;151:1093–1095.

Matarasso SL, Matarasso A. Treatment guidelines for botulinum toxin type A for the periocular region and a report on partial upper lip ptosis following injections to the lateral canthal rhytids. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2001;10:208–214.

Schwarze SR, Hruska KA, Dowdy SF. Protein transduction: unrestricted delivery into all cells? Trends in Cell Biology. 2000;10(7):290–295.

Scott AB. Botulinum toxin injection of eye muscles to correct strabismus. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1981;79:734–770.

Solomon P. Delivery of Botox by iontophoresis. British Journal of Dermatology. 2005;153:1075.

Spencer JM. Botulinum toxin B. The new option in cosmetic injection. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2002;1:17–22.