Chapter 375 Tonsils and Adenoids

Pathology

Acute Infection

Most episodes of acute pharyngotonsillitis are caused by viruses (Chapter 373). Group A β-hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS) is the most common cause of bacterial infection in the pharynx (Chapter 176).

Airway Obstruction

Both the tonsils and adenoids are a major cause of upper airway obstruction in children. Airway obstruction in children is typically manifested in sleep-disordered breathing, including obstructive sleep apnea, obstructive sleep hypopnea, and upper airway resistance syndrome (Chapter 17). Sleep-disordered breathing secondary to adenotonsillar breathing is a cause of growth failure (Chapter 38).

Clinical Manifestations

Acute Infection

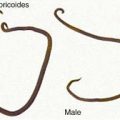

Symptoms of GABHS infection include odynophagia, dry throat, malaise, fever and chills, dysphagia, referred otalgia, headache, muscular aches, and enlarged cervical nodes. Signs include dry tongue, erythematous enlarged tonsils, tonsillar or pharyngeal exudate, palatine petechiae, and enlargement and tenderness of the jugulodigastric lymph nodes (Fig. 375–1; Chapters 176 and 373).

Airway Obstruction

In many children, the diagnosis of airway obstruction (Chapters 17 and 365) can be made by history and physical examination. Daytime symptoms of airway obstruction, secondary to adenotonsillar hypertrophy, include chronic mouth breathing, nasal obstruction, hyponasal speech, hyposmia, decreased appetite, poor school performance, and, rarely, symptoms of right-sided heart failure. Nighttime symptoms consist of loud snoring, choking, gasping, frank apneas, restless sleep, abnormal sleep positions, somnambulism, night terrors, diaphoresis, enuresis, and sleep talking. Large tonsils are typically seen on examination, although the absolute size might not indicate the degree of obstruction. The size of the adenoid tissue can be demonstrated on a lateral neck radiograph or with flexible endoscopy. Other signs that can contribute to airway obstruction include the presence of a craniofacial syndrome or hypotonia.

Treatment

Medical Management

The treatment of acute pharyngotonsillitis is discussed in Chapter 373 and antibiotic treatment of GABHS in Chapter 176. Because co-pathogens such as staphylococci or anaerobes can produce β-lactamase that can inactivate penicillin, the use of cephalosporins or clindamycin may be more efficacious in the treatment of chronic throat infections. Tonsillolith or debris may be expressed manually with either a cotton-tipped applicator or a water jet. Chronically infected tonsillar crypts can be cauterized using silver nitrate.

Complications

Acute Pharyngotonsillitis

The 2 major complications of untreated GABHS infection are post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis and acute rheumatic fever (Chapters 176 and 505.1).

Peritonsillar Infection

Peritonsillar infection can occur as either cellulitis or a frank abscess in the region superior and lateral to the tonsillar capsule (Chapter 374). These infections usually occur in children with a history of recurrent tonsillar infection and are polymicrobial, including both aerobes and anaerobes. Unilateral throat pain, referred otalgia, drooling, and trismus are presenting symptoms. The affected tonsil is displaced down and medial by swelling of the anterior tonsillar pillar and palate. The diagnosis of an abscess can be confirmed by CT or by needle aspiration, the contents of which should be sent for culture.

Retropharyngeal Space Infection

Infections in the retropharyngeal space develop in the lymph nodes that drain the oropharynx, nose, and nasopharynx. (See Chapter 374).

Parapharyngeal Space Infection

Tonsillar infection can extend into the parapharyngeal space, causing symptoms of fever, neck pain and stiffness, and signs of swelling of the lateral pharyngeal wall and neck on the affected side. The diagnosis is confirmed by contrast medium–enhanced CT, and treatment includes intravenous antibiotics and external incision and drainage if an abscess is demonstrated on CT (Chapter 374). Septic thrombophlebitis of the jugular vein, Lemierre syndrome, manifests with fever, toxicity, neck pain and stiffness, and respiratory distress due to multiple septic pulmonary emboli and is a complication of a parapharyngeal space or odontogenic infection from Fusobacterium necrophorum. Concurrent Epstein-Barr virus mononucleosis can be a predisposing event before the sudden onset of fever, chills, and respiratory distress in an adolescent patient. Treatment includes high-dose intravenous antibiotics (ampicillin-sulbactam, clindamycin, penicillin, or ciprofloxacin) and heparinization.

Chronic Airway Obstruction

The effects of chronic airway obstruction (Chapter 17) and mouth breathing on facial growth remain a subject of controversy. Studies of chronic mouth breathing, both in humans and animals, have shown changes in facial development, including prolongation of the total anterior facial height and a tendency toward a retrognathic mandible, the so-called adenoid facies. Adenotonsillectomy can reverse some of these abnormalities. Other studies have disputed these findings.

Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy

The risks and potential benefits of surgery must be considered (Table 375–1). Bleeding can occur in the immediate postoperative period or be delayed after separation of the eschar. Bleeding is more common after high dose dexamethasone (0.5 mg/kg), although postoperative nausea and emesis is reduced. The risk of bleeding is lower with lower-dose dexamethasone (0.15 mg/kg), which also has a lowered risk of postoperative nausea and emesis. Swelling of the tongue and soft palate can lead to acute airway obstruction in the 1st few hours after surgery. Children with underlying hypotonia or craniofacial anomalies are at greater risk for suffering this complication. Dehydration from odynophagia is not uncommon in the 1st postoperative week. Rare complications include velopharyngeal insufficiency, nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal stenosis, and psychologic problems.

Table 375-1 RISKS AND POTENTIAL BENEFITS OF TONSILLECTOMY OR ADENOIDECTOMY OR BOTH

RISKS

POTENTIAL BENEFITS

* Cost for tonsillectomy alone and adenoidectomy alone are somewhat lower.

Modified from Bluestone CD, editor: Pediatric otolaryngology, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2003 Saunders, p. 1213.

Al-Mazrou KA, Al-khattaf AS. Adherent biofilms in adenotonsillar diseases in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:20-23.

American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Clinical indicators: tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy, adenotonsillectomy, 2000. (website) www.entlink.net/practice/products/indicators/tonsillectomy.html Accessed June 17, 2010

Baugh RF, Archer SM, Mitchell RB, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillectomy in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(1 suppl):S1-S30.

Bonuck KA, Freeman K, Henderson J. Growth and growth biomarker changes after adenotonsillectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:83-91.

Brook I, Shah K. Bacteriology of adenoids and tonsils in children with recurrent adenotonsillitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:844-848.

Burton MJ, Glasziou PP: Tonsillectomy or adeno-tonsillectomy versus non-surgical treatment for chronic/recurrent acute tonsillitis, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD001802, 2009.

Buskens E, van Staaij B, van den Akker J, et al. Adenotonsillectomy or watchful waiting in patients with mild to moderate symptoms of throat infections or adenotonsillar hypertrophy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:1083-1088.

Czarnetzki C, Elia N, Lysakowski C, et al. Dexamethasone and risk of nausea and vomiting and postoperative bleeding after tonsillectomy in children. JAMA. 2008;300:2621-2630.

Johnson RF, Stewart MG, Wright CC. An evidence-based review of the treatment of peritonsillar abscess. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:332-343.

Mitchell RB. Adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea in children: outcome evaluated by pre- and postoperative polysomnography. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1844-1854.

Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Colborn DK, et al. Tonsillectomy and adenotonsillectomy for recurrent throat infection in moderately affected children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:7-15.

Ramirez S, Hild TG, Rudolph CN, et al. Increased diagnosis of Lemierre syndrome and other Fusobacterium necrophorum infections at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e380-e385.

Randall DA, Martin PJ, Thompson LDR. Routine histologic examination is unnecessary for tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1600-1604.