TONGUE COATING

TONGUE COATING

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF TONGUE COATING

The tongue coating reflects primarily the state of the Yang organs and especially of the Stomach. It also reflects conditions of Deficiency or Excess and of Heat or Cold (Box 26.1).

Observation of the tongue coating needs to be based on a careful analysis of the history of the patient because the tongue coating changes very rapidly in acute conditions and can reflect short-term variations. For example, a yellow tongue coating in the centre indicates Stomach-Heat and this could equally be a chronic condition of Stomach-Heat or simply an acute stomach upset. We therefore need to enquire carefully to exclude the possibility that the yellow coating merely reflects an acute but passing condition. Apart from the history, the brightness of the coating can give us an indication of its duration: the duller the coating, the more chronic is the condition.

Box 26.1 summarizes the significance of a tongue coating.

COATING WITH OR WITHOUT ROOT

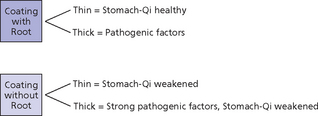

We can compare the tongue coating to grass: it should “grow” out of the tongue body just as grass grows out of the soil and it should have “roots” just as grass stems have roots in the earth. A coating with root reflects the normal functioning of Stomach-Qi even if the coating may be pathological (e.g. too thick and dark yellow). A coating without root resembles mown grass scattered on barren ground: it looks as if it has been “added” on top of the tongue rather than growing out of it. (See Plates 26.1a and b on p. P25.) In severe conditions, the rootless coating may look like salt or snow sprinkled on top of the tongue. A rootless coating indicates the beginning of the weakening of Stomach-Qi in the course of a chronic disease. Therefore, it is better to have a thick, pathological coating with root than to have a thin coating without root.

It should be emphasized that the coating with root is not necessarily thin, although that is the most common situation. The coating without root can also be thick and often sticky: this represents the worst scenario because it indicates that, on the one hand, Stomach-Qi is weakened and, on the other, that there is a significant pathogenic factor (against which the body is unable to fight due to the Stomach-Qi deficiency) (Fig. 26.1). For this reason it is obviously better to have a thin rather than a thick coating without root. (See Plate 26.1c on p. P25.)

Box 26.2 summarizes the four different situations seen in coating with and without root.

COATING DISTRIBUTION

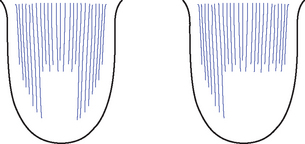

A pathogenic factor in the Gall-Bladder (Fig. 26.2) may be manifested in a variety of ways; the most common one is a bilateral or unilateral coating that comes forward in one or two strips on the edges. (See Plate 26.2 on p. P25.)

Fig. 26.2 Coating in the Gall-Bladder area

COATING TEXTURE

Sticky coating

The sticky (also called greasy) coating has an oily but coarse appearance and the individual papillae can still be seen. (See Plate 26.3 on p. P25.) To visualize a sticky coating, one can use the analogy of a toothbrush of very fine, natural hair spread with butter or lard: the toothbrush will appear very greasy but the individual hairs can still be seen. Thus, although the sticky coating is greasy and oily, it may also be, in addition, dry. This may seem a contradiction but it is not. To use the same analogy, we can think of a toothbrush with very fine hairs which has been spread with butter and left for several days; after that time, it will still have a greasy appearance but it will be dry. Thus, we should not identify “stickiness” of the tongue coating with wetness.

TONGUE COATING IN EXTERNAL DISEASES

The distribution of the coating also reflects the stages of penetration of an external pathogenic fac-tor. In the very beginning stages of an invasion of external Wind, the coating may be more concentrated on the front third or on the sides. In this context, these two areas correspond to the Exterior of the body while the centre of the tongue corresponds to the Interior. (See Fig. 24.8 on p. 212)