Chapter 7. Thromboembolic disease

Tests to identify venous thromboembolic disease255

Management of pulmonary thromboembolism257

Nursing the patient with a suspected DVT262

Introduction

The situation has changed, for two reasons:

• rapid and reliable screening tests are now available for venous thromboembolism

• simplified anticoagulation with once-daily subcutaneous low-molecularweight heparin is replacing the heparin infusion

There are two important clinical issues:

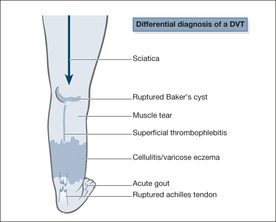

• differentiating between the various causes of a red, swollen and painful leg: venous thrombosis, cellulitis, varicose eczema and arterial insufficiency

• remembering to consider the possibility of pulmonary emboli in any ill and breathless patient – particularly where there is pleuritic chest pain

The overriding consideration in these situations is that a missed diagnosis of venous thromboembolic disease carries with it the potential of a preventable death from a massive pulmonary embolus. It should be remembered that post-mortem studies have shown that 10% of hospital deaths are due to pulmonary emboli; most of them were unrecognised.

The Nature of the Disease

Thrombosis and Thromboembolisation

Mechanisms

Thrombosis refers to the process in which a mass of clot forms inside an artery or a vein. It consists of a dense network of fibrin in which are trapped variable proportions of red cells and platelets. Thrombosis blocks the vessel and impairs blood flow. Arterial thrombosis leads to ischaemic tissue damage (myocardial infarction, stroke and peripheral vascular disease), whereas in venous thrombosis the consequences are due to back pressure and local swelling (oedema). If the clot disintegrates, parts of it can break off, producing emboli that travel onwards – in venous thrombosis through the veins to the lungs (pulmonary embolus), and in arterial thrombosis through the arteries to major organs such as the brain (cerebral embolus), limbs (peripheral embolus), kidneys (renal infarction) and intestine (acute bowel ischaemia).

Stagnation of the blood flow

Stagnation within the veins is the most important factor in initiating venous thrombosis. Calf muscles act as a venous pump returning blood to the heart. Failure of the calf pump due to enforced immobility (e.g. postoperative bed rest, plaster cast, paralysed limb) leads to venous stasis. This is a particular problem in the elderly, the obese and those with varicose veins: in these patients even 3 or 4 days of immobility can be critical.

Damage to the vein wall

Thrombosis is triggered by the activation of clotting mechanisms that occurs when there is damage to the vein wall – indeed, this is the normal mechanism for preventing bleeding at the sites of trauma. Typical situations that lead to vein damage are pressure injuries to the calf from the operating theatre table and the deterioration that occurs in the veins as a result of recurrent venous thrombosis.

Abnormalities of the clotting mechanism

There are several inherited and acquired abnormalities of the clotting mechanisms that increase the risk of venous thromboembolic disease (→Box 7.1). The most common acquired abnormalities are those associated with the oral contraceptive pill, hormone replacement therapy, pregnancy and the presence of malignant disease.

Box 7.1

• Antithrombin deficiency

• Protein C deficiency

• Antiphospholipid syndrome

• Protein S deficiency

• Factor V Leiden

Inherited clotting abnormalities (‘thrombophilias’) are increasingly recognised as underlying the cause of recurrent DVTs, particularly in younger patients and in those with a positive family history. The most important of several inherited coagulation abnormalities, known as Factor V Leiden, is present in 5% of the population and increases the risk of thrombosis by ten times the normal rate. One in five patients with their first DVT are Factor V Leiden positive. Recent estimates suggest up to half of all patients who present with a venous thromboembolic episode, either DVT or pulmonary embolus, may have a single or multiple inherited abnormalities of their clotting. In these individuals, each episode can be triggered by trivial external events such as minor surgery or immobility. In the future, increasing attention will be paid to identifying these inherited risk factors.

Multiple risk factors

In most situations in which the chances of a venous thrombosis are high there are multiple risk factors. Thus in major orthopaedic procedures to the leg there is vein damage and immobility; in pregnancy there is abnormal clotting and stagnation of blood due to intraabdominal mechanical effects; and in prolonged air travel there is immobility, often associated with a degree of dehydration. The combination of the oral contraceptive pill and the presence of Factor V Leiden increases the risk of a DVT 30-fold.

Major risk factors

In a patient with suspicious symptoms, the presence of major risk factors (those that increase the risk by between 5 and 20 times normal) makes the diagnosis of a pulmonary embolism much more likely.

• Recent surgery (hip and knee replacement, major abdominal and pelvic surgery)

• Decreased mobility (institutional care, prolonged hospital stay)

• Malignancy

• Lower limb problems (post phlebitic limb, varicose veins)

• Pregnancy (not the pill) especially third trimester and post delivery/ caesarian

• Previous DVT/PE

Superficial thrombophlebitis

Thrombophlebitis is a painful inflammation of the superficial veins. Classically it is seen with infected venous cannulae, but it also commonly occurs in patients with varicose veins. The clinical picture is of palpable and very tender cords of thrombosed and inflamed veins, with the overlying skin appearing reddened or bruised. Thrombophlebitis is not in itself dangerous: it does not progress to, but may accompany, deep vein thrombosis. Management is based on removing any cause (e.g. an i.v. cannula) and treating the symptoms. Importantly, recurrent unexplained phlebitis is found in patients with unrecognised malignant disease, particularly adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract and lung.

Deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis is a more serious problem, because of the risk of fatal pulmonary embolus. Most DVTs start in the deep veins of the calf, termed the distal veins, where they cause local pain and swelling.

The management is based on preventing progression of the thrombotic process by using heparin for an immediate effect, followed by warfarin in the medium to long term to lower the risk of recurrence. The aim of treatment is to stabilise the situation. Warfarin and heparin do not dissolve established clots: they are given to:

• prevent extension

• reduce the chances of embolisation

• lower the risk of recurrence

Pulmonary thromboembolism

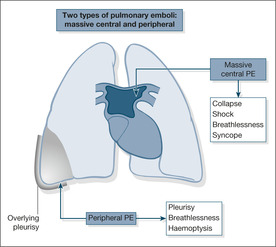

Most pulmonary emboli (90%) arise from the proximal veins in the thigh and pelvis. Depending on their size, emboli that travel to the lung either become wedged in the main pulmonary arteries, where they block the outflow of blood from the right side of the heart, or pass onwards to become trapped in the lung peripheries. The former, termed massive pulmonary emboli, produce a disastrous decrease in cardiac output, leading to sudden death or acute hypotensive collapse. The smaller emboli in the periphery of the lungs produce wedge-shaped areas of lung damage (producing breathlessness and haemoptysis) and give rise to overlying pleurisy (acute chest pain and a fever; →Fig. 7.1).

Massive pulmonary emboli can move or start to break up either naturally or during the course of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Thrombolytic drugs such as streptokinase and rt-PA can help to dissolve the embolus and are used in the unstable hypotensive patient. Heparin will prevent further emboli, and as most patients who survive the first embolus die from a recurrence within the first few hours, it is important to start treatment urgently. Warfarin is added for longer-term prevention.

The management of smaller peripheral emboli is based on preventing further and possibly bigger emboli by giving heparin and, subsequently, warfarin.

Reducing the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)

There is a significant risk that the admission of a patient with an acute medical illness is complicated by a DVT and/or pulmonary embolus. This risk should be assessed in every patient and if it is significant, preventative measures – either drugs (LMWH or fondaparinix) or mechanical measures (thigh-length anti-embolism stockings) should be considered.

Significant risk of VTE in an acute medical admission is defined as:

• decreased mobility anticipated for three days or more or one or more of the following risk factors

• age > 60

• obese (BMI > 30)

• medical co-morbidities (diabetes, CCF, COPD, chronic arthritis etc.)

• active malignancy

• phlebitic lower limbs

• pregnant with an associated risk factor (e.g. age >35, hyperemesis, ovarian hyperstimulation)

• HRT or the oral contraceptive

Tests to Identify Venous Thromboembolic Disease

Diagnostic approach single : assessing the probability of a PE

Confirmatory tests are chosen according to the clinical likelihood of a PE and the presence or absence of major risk factors (page 254). If the clinical picture is consistent with a PE, and the patient has no other obvious alternative diagnosis such as pneumonia or COPD, the presence of a major risk factor makes the probability of a PE high. If the clinical picture is consistent with a PE but the patient has either no obvious alternative diagnosis or a major risk factor, the probability of a PE is intermediate. If the clinical picture would fit a PE but there is an obvious alternative diagnosis and no major risk factor, the probability of a PE is low. High probability patients should start heparin immediately and need a definitive test (CTPA or isotope lung scan) – patients where the probability of a PE is intermediate or low should have the screening blood test (D-dimer) which, if it is normal, rules out a PE. A normal D-dimer test can give false reassurance in cases where the clinical suspicion is scored high – in this situation the test should not be done.

A number of tests are available to identify venous thromboembolic disease (→Table 7.1). They are described in more detail below.

| Test | Good at: | Poor at: |

|---|---|---|

| V/Q lung scan | Diagnosing a PE if the chest film is normal | Diagnosing a PE if there is pre-existing lung disease |

| Contrast venogram | The ‘gold standard’ test | Too invasive for a screening test (replaced by CTPA) |

| Impedence plethysmography | Diagnosing a proximal (above knee) DVT | Diagnosing a distal (calf vein) DVT |

| D-dimers | Excluding a DVT if the test is normal. Also positive in PE |

False positive result in other conditions, e.g. infection and myocardial infarct |

| Compression ultrasound | A good screening test | Diagnosing a distal (calf vein) thrombosis |

CT pulmonary angiogram

The investigation of possible pulmonary emboli has been revolutionised by the introduction of the CTPA. It is superior to both the isotope lung scan and the conventional angiogram. A negative CTPA rules out a significant pulmonary embolus and often gives additional information on alternative causes of the patient’s symptoms.

Isotope lung scan

Lung scans are easy to perform and, when used in conjunction with the clinical details, are useful in the diagnosis of pulmonary emboli. Although positive scans are also seen in other conditions and have to be interpreted with care, a normal scan result is very helpful, as it rules out the possibility of a pulmonary embolus.

D-dimer measurements

D-dimers are fragments of dissolving blood clots that can be identified from a blood sample whenever a thromboembolic process is under way. A positive test is also seen after surgery, in infections, after myocardial infarction and in malignant disease: a positive D-dimer test is not therefore in itself diagnostic. D-dimer tests are most useful for ruling out thromboembolism when the initial clinical assessment suggests a low or intermediate suspicion of the diagnosis. For example a patient who is breathless may have a major risk factor such as recent hip surgery, but has other possible causes of breathlessness such as COPD: in this situation, a negative D-dimer means there is another cause for the breathlessness. When the clinical suspicion is high, D-dimers are not helpful, because a negative result under these circumstances is not reliable enough to rule out the diagnosis (an example would be a patient who is breathless, with no alternative explanation, plus a major risk factor for pulmonary embolus).

Compression ultrasound

This looks at compressibility of the vein with an ultrasound probe and also examines venous blood flow using colour Doppler. Compression ultrasound is accurate for thigh vein thrombosis, but not for thrombosis in the pelvis or calf. It is also unreliable at picking up recurrent thrombotic episodes. In spite of these drawbacks, ultrasound is a simple, rapid and very effective diagnostic tool, particularly when combined with clinical assessment and initial screening by the measurement of D-dimers. If a DVT is thought likely (based on clinical assessment in the form of a scoring system – page 265 and an elevated D-dimers) but a compression scan is negative, the scan should be repeated in seven days in case a calf vein thrombosis (not dangerous) has extended above the knee to involve the thigh veins (dangerous).

Contrast venogram and pulmonary angiogram

The venogram examines the veins of the legs and pelvis and the inferior vena cava and is considered to be the ‘gold standard’ for the identification of venous thrombosis. An invasive test and unpleasant for the patient, its use is confined to difficult cases, particularly those in which active intervention with a vena cava filter is under consideration. The pulmonary angiogram was the ‘gold standard’ investigation for diagnosing pulmonary emboli, but it has been replaced by the CT pulmonary angiogram.

Impedance plethysmography

In this test, the flow of blood out of the calf is impeded by inflating a thigh cuff. The cuff is then suddenly let down and the flow of blood out of the calf is measured to assess the degree of venous obstruction. The term ‘impedance’ refers to the technique of deriving a measure of blood flow from sensors placed over the calf.

Ultrasound and plethysmography are reliable for proximal deep vein thrombosis, but are poor at identifying calf vein thrombosis. However, in practical terms (i.e. the risk of pulmonary embolus) thrombosis in the calf only becomes important if it spreads to the thigh – so if the initial clinical suspicion is high it is prudent to repeat either test after a few days, in case a missed calf vein thrombosis has extended proximally to the thigh.

Management of Pulmonary Thromboembolism

The following case studies are used to illustrate management of pulmonary thromboembolism (→Case Study 7.1, Case Studies 7.2, Case Study 7.3 and Case Studies 7.4). The classic features of a pulmonary embolus are listed in Box 7.2.

Case Study 7.1

A 35-year-old woman was admitted to hospital having collapsed at home. She had arisen to go to the toilet and collapsed with loss of consciousness for a few seconds. She recovered, but remained clammy with a thready pulse and felt very breathless.The day before, she had complained of a slight pain in the left calf. She was taking a third-generation combined oral contraceptive pill, she was obese and was a smoker. She also had chronic bilateral varicose veins.Three months earlier, she had been admitted with swelling and tenderness of the left calf coming on after exercise, but after equivocal tests had been discharged without anticoagulation.

On examination her pulse was 110 beats/min, blood pressure 104/78mmHg, oxygen saturations 100% on 6L/min oxygen. Respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min.The right calf measured 42cm and the left 46cm (similar readings to the previous admission). An urgent lung scan showed multiple pulmonary emboli. Seven hours after admission, she collapsed again while walking to the toilet, but on this occasion there was a cardiorespiratory arrest. In spite of prolonged resuscitation and the use of streptokinase, she remained in electromechanical dissociation (EMD) and did not survive.

Case Studies 7.2

CASE 1

A 54-year-old woman was admitted with a 1-week history of right upper abdominal pain radiating to her back and right shoulder and worse on lying or on deep inspiration. She had become breathless over 2 days.

On admission the patient had a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, pulse 80 beats/min and normal blood pressure.The arterial oxygen level was reduced to 88% on air and the chest film showed changes at both lung bases. A provisional diagnosis of diaphragmatic pleurisy due to pulmonary emboli was made and heparin was started.

On the second day the oxygen saturations fell to 76% on air and the pulse had increased to 110 beats/min. Examination and ECG showed increasing strain on the right side of the heart. On the third day there was a sudden attack of near syncope and breathlessness on standing associated with further drops in the oxygen saturation and a blood pressure of 90/60mmHg.The oxygen saturation remained low at 85% in spite of high-flow oxygen.

The lung scan showed multiple pulmonary emboli.Thrombolysis with i.v. streptokinase was started: 250 000 units over 30min then 100 000 units hourly for 72h. Her condition improved, with a fall in the pulse rate and an increase in the oxygen saturations.

A subsequent compression ultrasound showed an extensive right-sided proximal DVT.

CASE 2

A 64-year-old woman was admitted with a 5-day history of severe progressive breathlessness and exertional faintness.Two years earlier, extensive investigations for unexplained breathlessness concluded that the diagnosis was hyperventilation.

In her past history there had been extensive plastic surgery to the left calf. On admission she was obese, with bilateral ankle oedema. She was having episodic attacks of breathlessness and pain. Oxygen saturations were dropping to 70% on air. An urgent lung scan showed multiple pulmonary emboli. She was treated with i.v. heparin and then streptokinase, but remained very ill. Combined pulmonary angiogram and venogram showed multiple emboli originating from a left iliac vein thrombosis. A permanent inferior vena cava filter was inserted by the radiologist, to lie in the vena cava just below the renal veins.This prevented further emboli and she slowly recovered.

At review a year later, she remained well, with much improved exercise tolerance and significant weight loss. She was on life-long warfarin.

Case Study 7.3

A 67-year-old woman was admitted to hospital with a 1-week history of breathlessness on minimal exertion and 2 days of left-sided pleurisy. She had been immobile for a month with back pain and for 2 days the left leg had been swollen. She had been on tamoxifen for 4 years after a mastectomy for breast cancer, and was an insulin-dependent diabetic.

The lung scan showed multiple emboli; she was given tinzaparin, but because of increasing breathlessness she was also given rt-PA.

Case Studies 7.4

CASE 1

A 50-year-old man was admitted with a 48-h history of very severe right-sided pleurisy, breathlessness and haemoptysis.There was no history of calf pain and no other risk factors. He was sweaty but apyrexial, pulse 110 beats/min, respiratory rate 20 breaths/min, with shallow painful breathing. Oxygen saturation was 90% on air. He was in extreme pain and very anxious. His legs were normal and he was of a slim build.There was fresh haemoptysis. Chest film showed shadowing at the bases of both lungs. His white cell count was normal. He was given i.v. opiate analgesia, immediate oxygen and subcutaneous tinzaparin 12 000 units subcutaneously (175 units/kg). Urgent lung scans were arranged and were of high probability for pulmonary emboli.

CASE 2

A 45-year-old overweight man was admitted with haemoptysis and severe right-sided pleurisy. He had a week’s history of flu-like symptoms culminating in a wheezy sounding productive cough. For 48h his sputum had been green but then became blood-stained and then brown. His legs had been normal and there were no risk factors apart from obesity. His pulse was 100 beats/min, temperature 38.5°C, saturations 97% on air.There was a brassy sounding painful cough and brown mucopurulent sputum. His calves were normal. Chest film was normal and the white cell count was elevated at 15 000 × 109/L. He was started on antibiotics and analgesiscs (NSAIDs). A lung scan was requested as a precaution and was reported to be normal.

Box 7.2

• Pleuritic chest pain

• Breathlessness

• Respiratory rate > 20 breaths/min

• Haemoptysis

There are two problems with the patient in Case Study 7.3– the management of recalcitrant pulmonary emboli, but also the problem of assessing her swollen leg. The assessment of a painful calf in a patient with diabetes needs care, because the diagnostic possibilities include:

• cellulitis

• critical limb ischaemia

• DVT

In cellulitis, there is a clear upper limit of demarcation to a swollen red limb. In critical ischaemia due to arterial ischaemia, the leg can be red and swollen, particularly if the patient has been sitting with the leg in a dependent position. Importantly, the limb will be cool, probably pulseless, and will lose its colour when it is elevated.

• Differentiating between an acute chest infection with pleurisy and a pulmonary embolism can be difficult. Key symptoms are chest pain, breathlessness and syncope

• Oxygen saturations (on air) are commonly below 92% (but can be normal)

• For all pulmonary emboli, the 3-month mortality rate is 15%, but patients who do particularly badly are:

— the elderly

— those with COPD

— those with congestive cardiac failure

— those who have underlying malignancy

Critical nursing tasks in acute pulmonary embolus

ABCDE: Immediate resuscitation

If the patient has collapsed with a cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation is started without delay. A massive embolus can present with a cardiac arrest, typically in the form of electromechanical dissociation (an ECG rhythm trace, but no palpable pulse or blood pressure).

Ensure adequate oxygenation

A major embolus cuts off the circulation to the lung, so the patient becomes acutely cyanosed. Immediate high-flow oxygen with a tight-fitting mask and a non-rebreathing bag is indicated to correct this. Intubation and ventilation may be needed in extreme cases.

Provide an adequate circulation

There is an immediate decrease in cardiac output, due to interruption of the circulation by the clot. The blood pressure falls dramatically even though the heart may continue to beat strongly. To help the heart by maximising venous return, the patient must be kept flat with the legs raised. A persistently low blood pressure is an indication for i.v. fluids. However, it is unwise to give, say, more than 500ml of isotonic saline, as the right side of the heart is already under strain and may not cope with a large volume load.

If these measures do not restore the blood pressure, then inotropic support is needed: the options are noradrenaline (norepinephrine), dopamine, dobutamine and adrenaline (epinephrine). Drugs such as GTN or frusemide are contraindicated, as they will reduce an already dangerously low blood pressure.

Important nursing tasks in acute pulmonary embolus

Assess the response to treatment

While resuscitation continues, the pulse, blood pressure and oxygen saturation need to be measured every few minutes. Persistent hypotension and tachycardia, in spite of efforts to restore the circulation, suggest that the clot has not shifted and that it continues to obstruct the circulation to the lung. Repeated urgent blood gas measurements will be needed during the initial phase.

Anticipate the need for urgent heparin therapy or thrombolysis

If the initial management is successful and the patient’s condition stabilises, heparin is used to prevent further, and possibly fatal, emboli. The choice lies between i.v. heparin as an initial bolus, then infusion, and subcutaneous lowmolecular-weight heparin. Heparin prevents further clotting and allows the body’s natural enzymes to disperse existing clots. In the patient who remains hypotensive and ill, the thrombolytic, rt-PA, can be used to help break up the emboli more rapidly. The recommended treatment is a 50-mg bolus of i.v. alteplase.

Prepare the patient for further procedures

Further tests may be needed to confirm the diagnosis, usually a CTPA or an isotope lung scan in medical physics or, less commonly, a pulmonary angiogram. A pulmonary angiogram is primarily diagnostic, but it can help the patient directly if the catheter is used to dislodge the clot or to put thrombolytic drugs such as rt-PA directly into the pulmonary vessels where the embolus is lodged.

If, despite adequate anticoagulation, there are recurrent emboli arising from residual clots in the deep veins, filter devices can be placed in the inferior vena cava. These are effective in preventing further emboli and are usually well tolerated.

Pulmonary embolism in pregnancy

The main cause of pregnancy related death in the developed world is pulmonary embolism – the risk is greatest in the third trimester and postcaesarian section. The diagnosis can be difficult: D-dimers are often elevated in pregnancy and there are concerns about exposing mother and foetus to unnecessary radiation. During the first two trimesters a CTPA probably exposes the foetus to less radiation than a perfusion scan – during the third trimester they are about equal. Exposure levels from both tests (60 to 130μGy), however, are well below those which could be harmful (50,000μGy). The implications of a missed diagnosis are so grave that the most helpful test has to be selected – this will usually be a CTPA. Pregnancy does not influence the emergency treatment but subsequent prevention is based on daily lowmolecular weight heparin as warfarin can harm foetal development.

Answering Relatives’ Questions in Pulmonary Embolism

Why did the patient collapse? A blood clot became dislodged from a thrombosis in the leg and travelled to the lungs, where it became trapped, preventing blood from leaving the heart and reaching the lungs. In effect, circulation of the blood stopped at that point.

What are the risks from a pulmonary embolus? The risks of death in a pulmonary embolus are about 5% (reduced from 30% by treatment).

Is it the clot that is being coughed up? No. The blood-stained sputum is from lung tissue that has been starved of oxygen because the clot has cut off its blood supply.

What happens to the clot? It will break up and dissolve through the body’s natural anticoagulants, helped by the treatment he is receiving from us. Warfarin and heparin prevent the clot spreading, whereas streptokinase or rtPA actually melt any clot away.

What are the risks of further emboli now that the patient is on heparin? They are very low indeed (although not reduced to zero). The heparin will be followed by a variable time on warfarin tablets to reduce the risk even further.

Nursing the Patient With a Suspected DVT

The history and examination are unreliable in the diagnosis of venous thrombosis. Seventy percent of patients who are initially thought to have a DVT will prove to have an alternative diagnosis. Conversely, patients can present with a major pulmonary embolus that has arisen from a completely silent DVT.

There is a high cost for missing a proximal DVT: a 50% chance of a further episode and a 10% chance of a fatal PE within 3 months. The emphasis is therefore on using the combination of key clinical features and further investigations to ensure that the number missed is kept to a minimum.

Nursing assessment of a possible DVT

Risk factors from the patient’s history

The major risk factors are:

• lower limb immobility

• major surgery within previous 4 weeks

• more than two first-degree relatives with a history of DVTs

• active cancer within the previous 6 months

• recently bedridden for more than 3 days

Lower limb immobility. After a stroke, a paralysed lower limb often develops chronic ankle oedema, so the diagnosis of a DVT can be difficult, particularly if there is a problem with communication. The risks are similar if a limb is immobilised in a plaster cast.

Surgery within previous 4 weeks. Venous thrombosis is especially common after hip and knee replacements and can occur 4–6 weeks after surgery. Diagnosis can be difficult because of swelling and discomfort due to the surgery itself, but investigations need to be pursued, because 20% of patients undergoing a major lower limb joint replacement will develop a DVT despite prophylactic subcutaneous heparin in the immediate postoperative period.

Cancer. Active malignant disease within the previous 6 months increases the risk of DVT. Malignancy, particularly in the lung, prostate and pancreas, can also present as unexplained, often recurrent, venous thrombosis.

Positive family history. There is increasing recognition of the importance of a positive history of venous thromboembolic disease in first-degree relatives. The inherited thrombophilias are passed on to half of the offspring, as they are all inherited as autosomal dominant characteristics.

Other important features in the history

Previous DVT/PE. A previous thromboembolic episode is a major risk factor. The recurrence rate at 5 years is 25%; it is particularly high if there are residual associated risk factors such as malignant disease or immobility.

Obesity. Obesity is an important risk factor for both DVT and cellulitis. Commonly, obese middle-aged and elderly medical patients have chronically swollen and oedematous ankles, with areas of pigmentation, old healed varicose ulceration and discrete cellulitic looking areas. These legs can be difficult to assess, in particular to differentiate between acute and long-standing changes.

Examination of the legs

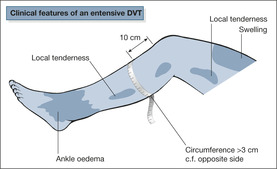

There are three important signs of venous thrombosis in the legs (→Fig. 7.2):

• local tenderness of the calf or thigh

• swelling of the calf and thigh

• unilateral calf swelling (> 3cm at 10cm below the tibial tuberosity)

Three additional signs may be present:

• ankle oedema

• unilateral dilated veins

• calf redness

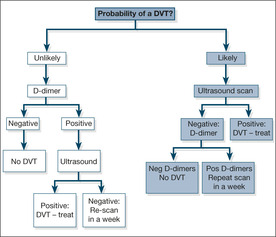

There is increasing interest in using procedures that combine the results of clinical assessment in the form of a scoring system with the result of a screening test procedure such as the D-dimer tests to determine the next step: immediate discharge, immediate anticoagulation, or further investigation with lung scan, venogram or ultrasound (→Box 7.3, Fig. 7.3).

Box 7.3

| Clinical feature | Score |

|---|---|

| Active cancer (within the previous 6 months) | 1 |

| Paralysis or plaster cast | 1 |

| Bed rest for more than 3 days or major surgery within 1 month | 1 |

| Localised tenderness along the deep veins | 1 |

| Whole leg swollen | 1 |

| Unilateral calf swelling of more than 3cm | 1 |

| Unilateral pitting oedema | 1 |

| Distended superficial veins | 1 |

| Previous DVT | 1 |

| More likely alternative diagnosis | -2 |

| DVT unlikely | ≤1 |

| DVT likely | ≥2 |

*with permission from Wells et al. Lancet 1997; 350: 1795–1798.

A modified Well’s Score (Box 7.3) is used to score the patient’s DVT as likely or unlikely. If it is unlikely and the D-dimer is negative a DVT can be ruled out – if the D-dimer is positive a compression ultrasound is done to exclude a DVT. If a DVT is likely the definitive test, compression ultrasound, is done. Only if this negative is a D-dimer done which, if elevated (suggesting a calf vein clot, undetectable by ultrasound) leads to a follow up scan in seven days to exclude extension of the clot into the thigh.

Other causes of acute calf pain (→Fig. 7.4)

Pain arising from the knee joint

Mechanical pain from the knee is suggested by a sudden onset during twisting, turning or crouching. The joint may be swollen, stiff and tender. The history is particularly important in rupture of a Baker’s cyst, as the signs in the leg can be identical to those found in a DVT.

|

| Fig. 7.4 |

Muscle tears, ruptured Achilles’ tendon

The history is all important. Torn muscle fibres usually occur during exertion and may be associated with local bruising around the heel and side of the foot. Patients on long-term oral steroids are prone to rupture of the Achilles’ tendon, which may occur with surprisingly little effort – even using the stairs.

Sciatica

There is a clear relationship in the history of lifting or sudden straining, with the pain commonly radiating from the spine down the back of the leg. With the patient lying on his back, the pain can be triggered by lifting the affected leg straight up in the air.

Other causes of a swollen painful leg

Acutely swollen red legs: illustrative cases

The following case studies illustrate possible diagnoses for acutely swollen red legs (→Case Study 7.5, Case Study 7.6 and Case Study 7.7).

Case Study 7.5

Three weeks after a routine right hip replacement, a 55-year-old woman was admitted with an increasingly swollen and painful right leg.There had been mild postoperative swelling, but this had spread from the calf to the thigh. On examination the leg was swollen, oedematous, shiny and warm to the touch, both above and below the knee.The surgical wound was clean and well healed.

A diagnosis of iliofemoral thrombosis was made and the patient was started on tinzaparin 175 units/kg subcutaneously once daily.

• The risk of a post-arthroplasty DVT persists for up to 6 weeks

• Half of the patients will have had a silent pulmonary embolus by the time the DVT presents

Case Study 7.6

An obese 75-year-old man gave a 10-day history of an increasingly painful and swollen right leg. Initially the foot was red and extremely tender, but 3 days before admission the redness spread to involve the whole of the lower leg. He felt ill and shivery.

On examination, the pulse was 110 beats/min and temperature 38°C.The right calf and foot were hot, shiny, swollen and very tender.There was a deep purple/red discolouration of the lower leg, with a sudden line of demarcation 3 in (7.5cm) below the knee.There were some tender red streaks at the back of the calf, spreading upwards towards the buttocks.There was no obvious skin wound, but the spaces between the toes were soggy and inflamed. A diagnosis of acute cellulitis was made, with a site of entry presumed to be the infected web spaces. Intravenous benzyl penicillin 1.2g i.v. qds and flucloxacillin 1g i.v. qds were started and the leg was elevated and rested.The web spaces were treated with antifungal agents. Prophylactic tinzaparin 3500 units daily was given in view of the risks of a subsequent DVT.

Case Study 7.7

An 80-year-old man was admitted with bilateral, red, swollen legs and immobility. His legs had been troubling him for years: he had chronic varicose veins, a previous leg ulcer that had eventually healed, and intermittent ankle swelling. His main complaint was of skin irritation and itch from the legs. He also noticed that both legs would ‘break out’ and discharge fluid.

On examination, he looked well and was apyrexial.The lower legs were very discoloured by brown pigmentation surrounded by red and inflamed areas.The skin was crusty and flaking and covered in scratch marks up to the knees. There were also multiple small raised blisters, some of which were discharging fluid.The white cell count and blood cultures were negative.

A diagnosis of acute varicose eczema rather than cellulitis was made and after dermatological advice, the legs were cleaned with twice daily 1:10 000 potassium permanganate astringent solution and started on high-potency local steroid cream to the skin.

Cellulitis

Major risk factors for cellulitis are:

• chronic lymphoedema of the leg (chronic brawny non-pitting oedema)

• an obvious portal of entry such as a skin wound

• obesity

• previous leg ulcer

Necrotising fasciitis

NB: If the pain from a ‘cellulitic’ leg is extreme, worsening and seemingly out of proportion to the changes in the leg, it is important to consider the possibility of necrotising fasciitis, a deep, rapidly spreading soft tissue infection.

The main features of necrotising fasciitis are:

• extreme pain and localised numbness

• skin blisters and bullae

• necrotic skin

• hypotension

• WCC > 15.4 × 109/L and sodium < 135mmol/L

• history of i.v. drug abuse

Varicose eczema

Cellulitis can be confused with varicose eczema:

• in both conditions the legs are red and inflamed

• crusting and scaling are seen only in varicose eczema

• the skin is shiny and smooth in cellulitis

• if there is doubt, start i.v. antibiotics and seek dermatological help

Management of a DVT

AIM: To prevent extension of the thrombosis and prevent embolisation

• Identify risk factors before starting therapy

• Baseline FBC, prothrombin time, biochemistry, liver function tests, consider thrombophilia screen

• Obtain an accurate weight to determine the dose of low-molecular-weight heparin

• Identify any possible contraindications to anticoagulation therapy

• If thromboembolism is suspected and there is no contraindication: — give immediate subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin 150–200units/kg, depending on the heparin preparation

• Confirm the diagnosis (CTPA, lung scan, compression ultrasound, D-dimers, etc.)

• Give 10mg oral warfarin loading dose on the same day that the heparin is started

• Raise the leg and, in extensive thrombosis, apply class II elastic stockings

• If there is extensive swelling: immobilise for 48h to allow swelling to reduce, then mobilise in stockings

• Watch for ischaemia

— loss of sensation

— pain

— seek urgent medical assessment if ischaemia is suspected in a swollen leg

• When resting: in bed with leg elevated, not down

• Discharge with class II thigh-length hosiery and sleep with foot of bed raised

• Daily walks

• Encourage weight loss

• There is a 6% risk of venous ulceration and chronic disability

Outpatient management of venous thromboembolic disease?

Increasingly patients with an uncomplicated DVT are treated by specialist nurse-led teams entirely on an outpatient basis. This may be applicable to patients with a PE but careful selection is critical. Recent evidence suggests that patients with emboli large enough to put a strain on the right side of the heart, as identified from the echocardiogram and by elevation of the cardiac enzymes Troponin I and Troponin T, have a poor outlook – outpatient treatment would not be applicable.

Box 7.4 summarises the key points in mobilisation of a DVT patient in the first 24h.

Box 7.4

• Elevate and rest a tense swollen leg due to iliofemoral thrombosis

• Do not elevate a leg that may be ischaemic (be wary in the diabetic patient)

• Rest a leg affected by acute cellulitis

• Mobilise an uncomplicated DVT within the limits of patient comfort

• Do not allow any patient with a swollen leg to sit with the legs dependent. If the leg is elevated or subjected to pressure dressings, watch for ischaemia

— increasing pain

— increasing discolouration or pallor of the feet

— numbness, loss of sensation

— loss or absence of the pulses

Anticoagulation therapy

Intravenous heparin

Heparin increases the effect of the naturally occurring anticoagulant called antithrombin. There is a wide variation in the response to i.v. heparin, so that the treatment needs careful monitoring, using the APPT in order to individualise the dose. Inadequate initial therapy is associated with a much worse outcome. The aim is to anticoagulate to 1.5–2.5 times the control APPT. Intravenous heparin is continued for at least 4 days and should overlap with warfarin treatment until the INR is in the therapeutic range of 2.0–3.0 for at least 2 days.

Many audits have shown a tendency to undertreat patients with heparin, particularly in the first critical 24h: this problem can be minimised by the use of a heparin protocol.

Subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin

Low-molecular-weight heparin has replaced the heparin infusion on most medical units, because it is as effective in treating both DVT and pulmonary embolus. Its simplicity raises the prospect of outpatient treatment.

In contrast to conventional heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin:

• can be given once daily

• has a consistent action in every patient that is determined solely by the patient’s weight

• can be given as a fixed-dose subcutaneous injection

• does not require laboratory monitoring

Low-molecular-weight heparin is given for at least 5 days while warfarin is introduced, until the INR is within the therapeutic range (2.5–3.0) for 2 consecutive days.

Doses (using tinzaparin as an example)

Prophylaxis

Low-risk surgery. 3500 units of tinzaparin 2h pre-op and once daily for 7 days post-op.

High-risk surgery/high-risk medical condition, e.g. severe DKA. 50 units/kg 12h pre-op and once daily for 7 days

Treatment of thromboembolic event. 175 units/kg of tinzaparin once daily.

• Weigh the patient

— 100kg = 18 000 units per day

— 80kg = 14 000 units per day

— 55kg = 10 000 units per day

The doses of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparins are presented in Table 7.2.

| Heparin | DVT therapy | PE | Unstable angina |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enoxaparin | 150U/kg daily | Unlicensed | 100U/kg bd |

| Tinzaparin | 175U/kg daily | 175U/kg daily | Unlicensed |

| Dalteparin | 200U/kg daily | Unlicensed | 120U/kg bd |

Over-anticoagulation

The most common causes for over-anticoagulation are:

• drug interactions

• errors with warfarin therapy

• the development of cardiac failure

• deterioration in liver function

Many drugs increase the effect of warfarin: those most commonly implicated are broad-spectrum antibiotics. Progressive cardiac failure, particularly in the elderly, is often associated with a sudden deterioration in anticoagulant control – INR values of 10 or more are not uncommon. Liver disease itself prolongs the prothrombin time, so clearly its development would have a major effect on the patient who is also taking warfarin.

Once the INR increases above 5.0 there is a risk of bleeding. However, provided that there is no major blood loss, INR values in the range 4–8 can be managed by discontinuing warfarin treatment until the INR falls. If the INR is greater than 8, warfarin should be stopped and if there are additional risks for bleeding (e.g. over 70 years old, previous bleeding, nose bleeds) a small dose (0.5–2.5 mg orally of the i.v. preparation) of vitamin K should be given. This will partially reverse the effects of the warfarin.

In the presence of major bleeding, the warfarin is stopped and its effect completely reversed with vitamin K 5mg by slow i.v. injection. In addition, either FFP 15ml/kg or, if it is available, prothrombin complex concentrate 50 units/kg, is administered to restore the clotting factors. FFP is the main source of serious transfusion reactions and should only be considered when there is active and serious bleeding.

Excessive bleeding on heparin usually responds to stopping the heparin and, if necessary, transfusion. Intravenous protamine sulphate will neutralise heparin at a dose of 1mg per 100 units given slowly over 10min, but it only partially reverses low-molecular-weight heparin and no more than 40mg should be given at any one injection. Treatment can be repeated hourly. FFP is not indicated for heparin overdosage.

Critical nursing tasks in a suspected DVT

In a suspected thromboembolic event, give the first dose of heparin immediately

Once investigations are under way, the patient may be off the ward for some time during the critical first few hours. The safest course of action is, in the absence of an obvious contraindication, to give the first dose of subcutaneous heparin as soon as the initial assessment is completed.

Ensure there is adequate pain relief

A severely swollen leg will cause intense pain. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin are unsafe once warfarin has been started, and paracetamol may not be adequate. Oral dihydrocodeine or tramadol may be sufficient, but in extreme pain subcutaneous morphine 10mg 2–4-hourly may be needed.

Be vigilant for acute ischaemia

Any acutely oedematous leg is at risk from ischaemia as a result of increased soft tissue pressure compromising the circulation to the legs. Persistent or increasing pain is the main warning feature, but there may simply be colour change or loss of feeling in the leg.

Important nursing tasks in a suspected DVT

Care of pressure areas

The heels and sides of the feet are particularly vulnerable in cases of acutely swollen legs. Inspect these areas regularly, use pressure-relieving strategies, and encourage early mobilisation. Oedematous legs are prone to superficial skin infections, particularly if pre-existing foot hygiene is poor.

Reassure the patient

The prospect of a clot breaking off and travelling to the lungs terrifies most patients. They will want to know about mobilisation (to be encouraged once any severe swelling has resolved), about what exactly happens to the clot in the leg and when the swelling will disappear.

Document all current regular and intermittent medication

Document the target INR (usually 2.5)

It is important to oversee the anticoagulant therapy, particularly as the patient may be on and off the ward in the first 24h having tests, and there may be a delay, with associated uncertainty, before all the tests come back to the ward. This can lead to a delay in anticoagulation or failures in communication among the staff.

Ensure a warfarin loading schedule is followed by the prescribing doctors

Table 7.3 details the warfarin loading schedule, depending on INR.

| Day | INR | Warfarin |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | <1.4 | 10mg |

| 2 | <1.8 | 10mg |

| 1.8 | 1.0mg | |

| >1.8 | 0.5mg |

Answering Relatives’ Questions in DVT

Why did the thrombosis occur? There are three reasons that may be important: stagnation of the blood in the leg veins, damage to the walls of the veins that may have triggered it off, and an abnormality in the blood itself that can make it more liable to clot.

Is it because of the family history? It is increasingly recognised that, in many patients (especially those with recurrent episodes or unexplained DVT in young people), there is an inherited tendency that could also be present in close family members. Sometimes it becomes necessary to screen family members, because some of these abnormalities can be passed on.

Was it the result of bad postoperative nursing? Even with preventative measures (low-molecular-weight heparin, etc.), there remains a significant risk after any surgery, particularly complex surgery and major joint replacements.

Does the warfarin continue for life? It depends on the circumstances: for example, if a second DVT is treated with warfarin for 6 months the recurrence rate is 20%, compared with 2% if the warfarin is continued for life.

What about the contraceptive pill, pregnancy and HRT? The risk is increased in all three situations, but particularly in pregnancy. Even so, the overall figures are still low in absolute terms: of 100 000 women on a third-generation pill for a year, only 25 will suffer a thromboembolic event (→Table 7.4).

| Rate per 100 000 women per year | |

|---|---|

| Normal non-pregnant | 5 |

| 2nd generation combined pill | 15 |

| 3rd generation combined pill | 25 |

| Pregnant | 60 |

What are the risks of warfarin? Standard treatment with warfarin carries an annual risk of haemorrhage of 7% and of death of 0.2%.

Why is the leg still so swollen – will it ever go down completely? Thrombosis damages the valves in the veins that are necessary for the efficient return of blood from the legs to the heart. The leg may remain swollen for some time, and sometimes it may never return to normal. The situation can be helped by regular exercise, the use of support stockings and avoiding sitting with dependent legs.

Further Reading

Donnelly, R.; Hinwood, D.; London, N.J.M., ABC of arterial and venous disease: non-invasive methods of arterial and venous assessment, British Medical Journal 320 (2000) 698–701.

Pout, G.; Wimperis, J.; Dilks, G., Nurse-led outpatient treatment of deep vein thrombosis, Nursing Standard 13 (19) (1999) 39–41.

Websites

BTS Guidelines for the management of Pulmonary Embolus, http://www.britthoracic.org.uk/docs/PulmonaryEmbolismJUN03.pdf.

The diagnosis, investigation, and management of deep vein thrombosis, http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/326/7400/1180.