20 Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia is the most common coagulation disorder in the intensive care unit (ICU). Classically defined as a platelet count less than 150 × 109/L, thrombocytopenia is frequently classified according to whether platelets are consumed, sequestered, or underproduced in the bone marrow. However, a more practical classification takes into account the clinical setting (Table 20-1). In the ICU, thrombocytopenia occurs in up to 20% of all medical and 35% of all surgical admissions.1,2 It has many causes and results from the underlying disease plus the effects of medications that can impair platelet production and/or increase platelet consumption and destruction. The two most important causes of thrombocytopenia are sepsis and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). Sepsis is associated with thrombocytopenia in 35% to 59% of cases, whereas HIT is the cause in approximately 25% of ICU patients.1–5 The highest incidence of HIT is among patients on high doses of unfractionated heparin.6 It is estimated that 2% of cardiac medical patients, 15% of orthopedic patients, and up to half of patients who undergo cardiac bypass surgery develop HIT antibodies against platelet factor 4 (heparin/PF4) following exposure to unfractionated heparin. However, most patients with heparin/PF4 antibodies do not develop thrombocytopenia, an important consideration when interpreting commonly available diagnostic tests that detect such antibodies.7 The most important complication observed in patients with HIT is not bleeding but thrombosis, which occurs 30 times more frequently in patients with HIT than in the general population.6

TABLE 20-1 Differential Diagnosis of Thrombocytopenia

| Outpatients |

| Non-ICU and MICU Inpatients |

| Coronary Care Unit Inpatients |

| Emergency Room Patients |

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

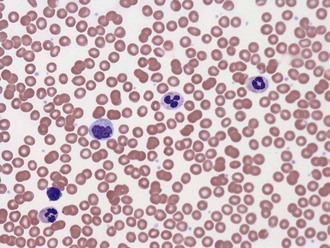

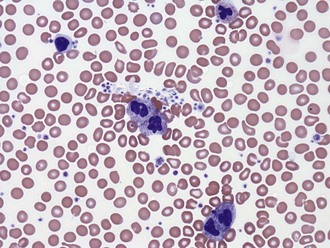

A common cause of low platelet count is test tube clumping of platelets due to ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-dependent antibodies or insufficient anticoagulant.8 When such “pseudothrombocytopenia” is considered as a possibility, the platelet count should be repeated in blood drawn into heparin- or citrate-containing tubes. Peripheral blood smears may help identify clumping platelets (Figures 20-1 and 20-2).

Immune mechanisms rarely contribute to sepsis-induced thrombocytopenia.8 Nonspecific platelet-associated antibodies can be detected in up to 30% of ICU patients. In these cases, nonpathogenic immunoglobulin G (IgG) presumably binds to bacterial products on the surface of platelets, to an altered platelet surface, or as immune complexes. A subset of patients with platelet-associated antibodies has autoantibodies directed against the integrin glycoprotein IIb/IIIa. These antibodies have been implicated in the pathogenesis of immune thrombocytopenic purpura and, although not proved, may also play a role in mediating sepsis-induced thrombocytopenia. Besides sepsis, many drugs also have been implicated in the production of nonspecific platelet antibodies, which is relevant, considering that the thrombocytopenia may be reversed by stopping the offending medication.9,10

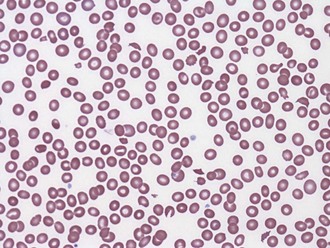

Nonimmune platelet destruction and/or consumption along with impaired production are the most important causes of thrombocytopenia in severe sepsis. There is increased binding of platelets to the activated endothelium, resulting in their sequestration, activation, and destruction. The inflammatory response to sepsis has been implicated directly in both impaired production and increased platelet destruction.4,5 Bone marrow specimens from patients with sepsis and thrombocytopenia often demonstrate hematophagocytosis.4,5 The degree to which this pathologic process is a cause or simply a marker of sepsis-related thrombocytopenia is unclear. Less commonly, thrombocytopenia is associated with underlying disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and thrombotic microangiopathic disorders such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and hemolysis-elevated liver enzymes and low platelet (HELLP) syndrome (Figure 20-3).11

HIT is a clinicopathologic syndrome diagnosed by the detection of circulating antibodies and thrombocytopenia with or without thrombosis.5,6 Even though the platelet count commonly drops during the first days after starting heparin, HIT itself occurs 5 to 10 days later and in less than 5% of all patients treated with unfractionated heparin for up to 7 days.5,6 An important exception to this rule is that patients who have been treated with heparin in the past 100 days are at risk for developing rapid-onset heparin-induced thrombocytopenia promptly on reexposure to any form of heparin, including flushes for IV lines.8 Low-molecular-weight heparins are much less frequently associated with HIT.5,12

In addition to sepsis and heparin-related mechanisms, other causes of thrombocytopenia should be considered in critically ill patients: medications that cause platelet destruction and/or bone marrow suppression; dilutional thrombocytopenia, particularly following trauma, surgery and/or multiple transfusions13; acute folate deficiency; and other preexisting diseases such as cancer, hypersplenism, and immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP).4,5,8

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Patients with thrombocytopenia may develop petechiae, purpura, bruising, or frank bleeding. The diagnosis of thrombocytopenia is made from the complete blood count and it may be important to examine the peripheral blood smear to rule out platelet clumping. Peripheral blood smears also may provide additional information concerning the etiology (e.g., large platelets may indicate increased platelet turnover and adequate marrow production). If thrombocytopenia is associated with consumptive coagulopathy, any or all of the following laboratory tests may be abnormal: International Normalized Ratio (INR), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), thrombin time, circulating concentration of D-dimer, plasma fibrinogen level, concentration of thrombin-antithrombin complexes, plasma concentration of prothrombin fragment 1.2, and the peripheral smear (presence of schistocytes). Although patients with sepsis may have increased platelet-associated IgG, this test is nonspecific and does not help in guiding therapy. Platelet dysfunction associated with renal disease or the use of aspirin and/or other cyclooxygenase inhibitors should also be considered in patients with abnormal cutaneous or mucosal bleeding.8

It is important to emphasize that thrombocytopenia associated with sepsis or HIT can coexist with an underlying hypercoagulable state, and that thrombotic complications may occur with a “normal” platelet count.5 Patients with HIT and thrombotic complications typically have mild to moderate reductions in platelet counts (median 60 × 109/L). Only 5% of cases are associated with platelet counts below 15 × 109/L.6,14 Findings suggestive of the diagnosis of HIT in these patients include a 30% to 50% or greater fall in the platelet count within the normal range or the presence of erythematous or necrotic skin lesions at subcutaneous heparin injection sites.

Prognosis

Prognosis

Thrombocytopenia is associated with longer ICU and hospital stays and is a predictor of mortality in ICU patients and patients with severe sepsis.1,3,5,8 The degree and duration of thrombocytopenia, as well as the net change in the platelet count, are important determinants of survival.1,3,5,8

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment of thrombocytopenia depends on the underlying cause. As a general rule, when thrombocytopenia is associated with an increased risk for bleeding and is not attributable to immune mechanisms, patients should be transfused with platelets to maintain a minimal platelet count. Although guidelines for prophylactic transfusions in patients with chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia have been established,14 the threshold for transfusing ICU patients is not clear.15 Thrombocytopenia is associated with increased risk of bleeding only when less than 50 × 109/L, when the risk increases four- to fivefold compared to patients with higher counts.5,8 Major surgeries and invasive procedures are not recommended when the platelet count is below 50 × 109/L. Spontaneous bleeding, particularly intracerebral, typically does not occur until the count drops to less than 20 × 109/L or (more likely) less than 10 × 109/L.5,8,15–17 In the absence of evidence-based guidelines, most patients are transfused to achieve a platelet count of above 10 × 109/L. If the patient has a concomitant coagulopathy (e.g., due to DIC or liver disease), active bleeding, or platelet dysfunction (e.g., due to uremia), it may be prudent to employ a more liberal transfusion strategy with the goal of maintaining an even higher platelet count. It is important to consider that platelet transfusions have inherent risks, including infection transmission, transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), and excessive clotting. Paradoxically, platelet transfusion may reduce endogenous platelet production by inactivating thrombopoietin.15

Patients with sepsis have an underlying shift in the hemostatic balance toward the procoagulant side. Indeed, platelets are activated in the setting of sepsis and likely contribute in important ways to the pathogenesis of the syndrome. When considering the cost-effectiveness of platelet transfusion, it is important to consider the theoretic risk of accelerating the underlying pathophysiology (i.e., “adding fuel to the fire”). The best approach for treating sepsis-associated thrombocytopenia is to treat the underlying infection with antibiotics and source control. Additional therapies may consist of some combination of low-tidal-volume ventilation,18 activated protein C,19 and early goal-directed therapy.20

The treatment of choice for HIT is to discontinue all heparin, including heparin flushes, and to institute therapy with an alternative rapid-acting anticoagulant that either inhibits thrombin or reduces thrombin generation. Warfarin, low-molecular-weight heparin, ε-aminocaproic acid (ancrod), and platelet transfusions should be avoided because they may exacerbate the underlying prothrombotic state. Two direct thrombin inhibitors, lepirudin and argatroban, have been evaluated and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia-related thrombosis.21 Selected patients with life- or limb-threatening thrombosis may benefit from adjuvant therapies, including thrombolytic drugs, surgical thromboembolectomy, intravenous gammaglobulin, plasmapheresis, and antiplatelet agents.

Rice TW, Wheeler AP. Coagulopathy in critically ill patients. Part 1: platelet disorders. Chest. 2009;136(6):1622-1630.

Overview of the most frequent causes of thrombocytopenia and their mechanisms.

Levi M, Opal S. Coagulation abnormalities in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2006;10(4):222-230.

Aird WC. The hematologic system as a marker of organ dysfunction in sepsis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(7):869-881.

Warkentin TE, Aird WC, Rand JH. Platelet-endothelial interactions: sepsis, HIT, and antiphospholipid syndrome. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2003:497-519.

1 Crowther MA, Cook DJ, Meade MO, et al. Thrombocytopenia in medical-surgical critically ill patients: prevalence, incidence, and risk factors. J Crit Care. 2005;20:348-353.

2 Aird WC. The hematologic system as a marker of organ dysfunction in sepsis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:869-881.

3 Sharma B, Sharma M, Majumder M, et al. Thrombocytopenia in septic shock patients: a prospective observational study of incidence, risk factors, and correlation with clinical outcome. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:874-880.

4 Levi M. The coagulant response in sepsis. Clin Chest Med 29. 2008:627-642.

5 Levi M, Opal SM. Coagulation abnormalities in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2006;10:222.

6 Arepally GM, Ortel TL. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:809-817.

7 Warkentin TE, Sheppard JAI, Moore JC, et al. Laboratory testing for the antibodies that cause heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: how much class do we need? J Lab Clin Med. 2005;146:341-346.

8 Rice TW, Wheeler AP. Coagulopathy in critically ill patients. Chest. 2009;136:1622-1630.

9 Aster RH, Bougie DW. Drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:580-587.

10 Visentin GP, Liu CY. Drug-induced thrombocytopenia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2007;21:685-696.

11 George JN. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1927-1935.

12 Martel N, Lee J, Wells PS. Risk for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin thromboprophylaxis: a meta-analysis. Blood. 2005:106-2710. 15

13 Nascimento B, Callum J, Rubenfeld G, Rezende Netto JB, Lin Y, Rizoli S. Fresh frozen plasma in massive bleedings: more questions than answers. Crit Care. 2010;14:202-209.

14 Girolami B, Prandoni P, Stefani PM, et al. The incidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in hospitalized medical patients treated with subcutaneous unfractionated heparin: a prospective cohort study. Blood. 2003;101:2955-2959.

15 Arnold DM, Crowther MA, Cook RJ, et al. Utilization of platelet transfusions in the intensive care unit: indications, transfusions, triggers, and platelet count responses. Transfusion. 2006;46:1286-1291.

16 Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699-709.

17 Oppenheim-Eden A, Glantz L, Eidelman LA, et al. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in critically ill patients: incidence over six years and associated factors. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:63-67.

18 Ardsnet. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301-1308.

19 Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699-709.

20 Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368-1377.

21 Warkentin TE, Aird WC, Rand JH. Platelet-endothelial interactions: Sepsis, HIT, and antiphospholipid syndrome. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2003:497-519.