Thought Disorders

Perspective

In the 1800s, Morel introduced the term dementia praecox to describe a progressive deterioration of mental functioning and behavior with onset in adolescence to early adult life.1 In 1911, Bleuler detailed the specifics of this disorder, which he termed schizophrenia, or “split-mindedness.”2 Early treatments of schizophrenia included ice water immersion, barbiturates or insulin to induce prolonged narcosis or coma, seizure induction with pentylenetetrazol, electroconvulsive therapy, and frontal leukotomy.3 The effectiveness of these treatments was marginal at best, and until recent times, most schizophrenic patients were relegated to lifelong institutionalization.

Modern-era pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia, with chlorpromazine and haloperidol, began in the early 1950s. This treatment proved so successful that by the 1960s, most psychiatrists believed that schizophrenia could be successfully managed in the outpatient setting. In 1965, the Community Mental Health Centers Act initiated the release of medicated schizophrenic patients into the community.4 Unfortunately, inadequate family support, unavailability of jobs and low-cost housing, and lack of funding for social services and outpatient psychiatric care left many of these individuals isolated without the tools needed for resocialization. Currently 20 to 40% of homeless people in the United States have a major mental illness.5 Emergency departments frequently serve as the primary entry point into the mental health care system for many of these individuals.6

Principles of Disease

The etiology of schizophrenia is currently believed to be heterogeneous from interaction of biologic and environmental factors. Studies involving adopted twins whose biologic parents have schizophrenia demonstrate a strong genetic basis for the disorder. Although the overall incidence of schizophrenia in the general population is roughly 1%, it is approximately 10% in first-degree biologic relatives of individuals with the disorder.7 With regard to the pathophysiologic mechanism of schizophrenia, dopaminergic, serotonergic, cholinergic, and glutamatergic systems have been implicated.8–11

Schizophrenia is also postulated to be a neurodevelopmental disorder resulting from the influence of environmental factors on genetically predisposed individuals. Disruptions in fetal brain development, caused by perinatal hypoxia, poor nutrition, infection, and other insults, may set the stage for subsequent development of schizophrenia.1,12 New imaging techniques have documented structural brain abnormalities, most of which appear to be developmental rather than degenerative in nature.8 Evidence supports the existence of a progressive continuum of psychotic illness, beginning with unipolar depression and progressing to bipolar illness, schizoaffective psychoses, and finally schizophrenia.1,13,14

Clinical Features

Phases of Schizophrenia

The development of schizophrenia involves three phases.15 The premorbid phase is characterized by the development of “negative” symptoms with deterioration in personal, social, and intellectual functioning. Patients progressively withdraw from social interactions and neglect personal appearance and hygiene, which negatively affects their work, school, and home life.

Criteria for Schizophrenia

The diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia (Box 110-1) are outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR).15

• The patient must exhibit two or more of the following symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior, and negative symptoms (such as flattening of affect, poverty of speech, or inability to perform goal-directed activities).

• There must be a sharp deterioration from the patient’s prior level of functioning (work, school, self-care, or interpersonal relations), and there must be continuous signs of disturbance for at least 6 months.

• The diagnoses of schizoaffective and mood disorders with psychotic features must be excluded.

• In evaluating these patients, emergency physicians must exclude myriad medical conditions that can mimic or cause psychotic symptoms.

Delusions

The DSM-IV-TR defines delusions as “erroneous beliefs that usually involve a misinterpretation of perceptions or experiences.”15 The delusions seen with schizophrenia are most often persecutory, religious, or somatic.

Diagnostic Strategies

Patients with Known Psychiatric Disorders

Patients with previously diagnosed thought disorders who present with mild to moderate exacerbation of their symptoms do not require extensive laboratory evaluation.16 Because some of these patients may have coexisting substance abuse or undiagnosed medical disorders, a thorough history, detailed physical examination, and routine toxicology studies are indicated for most patients.17–19 Patients exhibiting severe exacerbation of symptoms accompanied by marked agitation, violent behavior, or significantly abnormal vital signs should undergo more extensive evaluation.

Patients without Known Psychiatric Disorders

Many toxicologic and medical disorders can mimic schizophrenia. Patients with the apparent new onset of psychosis should receive a medical evaluation to exclude toxicologic and medical disorders.20–23 Both the DSM-IV-TR and review articles on this topic emphasize that most toxicologic and medical causes of altered mental status that simulate acute schizophrenia are best recognized by patterns of presentation combined with focused testing based on one’s index of suspicion for nonpsychiatric disease, rather than the reliance on a broad use of screening tests.

Differential Considerations

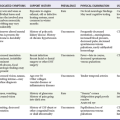

Certain medications and medical disorders may affect thought processes, causing patients to exhibit abnormal behavior (Boxes 110-2 and 110-3). This behavior may range from mild personality changes to apparent acute psychosis, even in the absence of an underlying psychiatric disorder.1 Factors that should alert one to a medical disorder include the following: history of substance abuse or a medical disorder requiring medication; patient’s age older than 35 years without previous evidence of psychiatric disease; recent fluctuation in behavioral symptoms; hallucinations that are primarily visual in nature; presence of lethargy; abnormal vital signs; and poor performance on cognitive function testing, particularly orientation to time, place, and person. These and other factors may be helpful in differentiating functional (psychiatric) from organic (medical) causes of abnormal behavior and can be easily recalled with the mnemonic MADFOCS (Table 110-1).24

Table 110-1

Factors in Differentiating Organic and Functional Psychosis: MADFOCS

| ORGANIC | FUNCTIONAL | |

| Memory deficits | Recent impairment | Remote impairment |

| Activity | Psychomotor retardation | Repetitive activity |

| Tremor | Posturing | |

| Ataxia | Rocking | |

| Distortions | Visual hallucinations | Auditory hallucinations |

| Feelings | Emotional lability | Flat affect |

| Orientation | Disoriented | Oriented |

| Cognition | Islands of lucidity | Continuous scattered thoughts |

| Perceives occasionally | Unfiltered perceptions | |

| Attends occasionally | Unable to attend | |

| Focuses | Unable to focus | |

| Some other findings | Age > 40 years | Age < 40 years |

| Sudden onset | Gradual onset | |

| Physical examination findings often abnormal | Physical examination findings normal | |

| Vital signs may be abnormal | Vital signs usually normal | |

| Social immodesty | Social modesty | |

| Aphasia | Intelligible speech | |

| Consciousness impaired | Awake and alert |

Modified from Frame DS, Kercher EE: Acute psychosis: Functional vs. organic. Emerg Med Clin North Am 9:123, 1991.

Although the classic textbook differentiation between functional and organic causes of abnormal behavior is straightforward, the evaluation of individual patients may be difficult.21 A patient with underlying psychiatric disease may develop a medical disorder, which may worsen the patient’s behavioral symptoms and further cloud the distinction between functional and organic disease. This evaluation is particularly difficult in the emergency department when previous medical or psychiatric history is not available, the patient is uncooperative, and the time frame to make a disposition is brief. When the clinical differentiation between functional and organic disease is unclear on the basis of available information, a patient should be thoroughly evaluated to exclude a toxicologic or medical disorder.

Psychiatric Disorders

A previously undiagnosed patient who presents with an acute functional psychosis may ultimately be given one of several psychiatric diagnoses.15 A brief psychotic disorder involves the sudden onset of psychotic symptoms in response to major stress and lasts several days to 1 month. Patients with schizophreniform disorder have similar symptoms that last longer than 1 month but less than 6 months. Whereas one third of individuals initially given the diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder recover within 6 months, the other two thirds retain their symptoms and are diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Patients with mood disorders may develop psychotic symptoms. If these symptoms are present only during periods of mood disturbance, the diagnosis of mood disorder with psychotic features is applied; if they persist longer than 2 weeks in the absence of prominent mood symptoms, the diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder is made. Patients with personality disorders may occasionally develop brief psychotic episodes under stress.

Management

Each patient should have a thorough history and physical examination, including a detailed mental status evaluation, to rule out an organic brain syndrome. Valuable information can be obtained from family members, friends, coworkers, neighbors, prehospital personnel, police, and previous medical records (see Table 110-1).24

Do you understand why you have been brought here today?

You seem to be upset. Can you tell me why?

Do you have any idea why you might be having these symptoms?

The patient’s appearance, body language, affect, and speech are observed during the responses to these questions.

Rapid Tranquilization

When psychotic patients exhibit behavior that is violent or so disorganized and uncooperative that clinical evaluation is impossible, the temporary use of physical restraints is indicated while rapid tranquilization is initiated (see Chapter 189). The technique of rapid tranquilization involves serial doses of a high-potency antipsychotic agent until target symptoms, such as agitation and excessive psychomotor activity, are improved. The goal is to facilitate cooperation of the patient without causing unnecessary sedation, which inhibits further medical and psychiatric assessment. Oral, intramuscular, or intravenous doses can be given every 30 to 60 minutes until the patient becomes calm and more cooperative. If the patient is willing, an oral concentrate is preferred as it implies consent and takes effect almost as quickly as with intramuscular administration.

Haloperidol (Haldol), a butyrophenone, is widely used for rapid tranquilization in the United States.25–27 The initial dose is 5 to 10 mg intramuscularly or intravenously for young to middle-aged patients and 0.5 to 2.0 mg intramuscularly or intravenously for elderly patients. Although rapid tranquilization with haloperidol quickly reduces tension, anxiety, and hyperactivity, delusions and hallucinations may not resolve for several weeks. In 2007 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a non–black box warning about sudden death with the use of haloperidol in large doses or through the intravenous route. Droperidol (Inapsine), another butyrophenone, has also been extensively used for this indication in doses of 2.5 to 5.0 mg intramuscularly or intravenously.28,29 Compared with haloperidol, droperidol has a faster onset and shorter duration of action and causes slightly more sedation. In 2001 the FDA issued a black box warning because of reports of a potential association between droperidol and prolonged QT interval, torsades de pointes, and sudden death.30 Despite subsequent studies supporting both the efficacy and safety of droperidol, the FDA warning has resulted in a significant decrease of its use in clinical practice.31,32 Neuroleptics should not be used for pregnant or lactating women, phencyclidine overdose, or anticholinergic drug–induced psychosis. In addition, although they may be useful to manage agitation in drug or alcohol intoxication, they should not be used as the sole agent in patients with drug or alcohol withdrawal. Newer atypical antipsychotic agents appear to have a broader spectrum of response with fewer side effects than the typical agents. These medications are available in tablet form and should be considered for patients who consent to oral medication. However, oral administration of a pharmacologic agent during an acute episode of agitation and psychosis is usually impossible. Ziprasidone (Geodon), aripiprazole (Abilify), and olanzapine (Zyprexa) are newer atypical antipsychotics currently approved in the United States for intramuscular injection.33 For ziprasidone, the initial dose is 20 mg intramuscularly, and it can be repeated every 4 hours. It is more effective than haloperidol for sedation and with fewer extrapyramidal side effects, but it is not yet widely used in the emergency department setting.34,35

Benzodiazepines are effective in managing agitation in patients who have alcohol or sedative-hypnotic withdrawal, cocaine intoxication, or a contraindication to neuroleptic use. Benzodiazepines are helpful adjuncts to neuroleptic medication in providing rapid tranquilization, particularly for combativeness or severe agitation. Lorazepam (Ativan), 1 to 2 mg, is frequently mixed with haloperidol, 5 mg, in the same syringe and administered intramuscularly or intravenously for this purpose.27 Benzodiazepines have also been shown to mitigate catatonic signs in schizophrenic patients.36 Disadvantages of benzodiazepines are the need for repeated dosing and the close monitoring required for potential respiratory depression with large doses.37

Outpatient Management

Box 110-4 lists the most common neuroleptic medications currently used in the United States.38–44 The mechanism of action is related to the blockade of dopamine receptors in the central nervous system, particularly dopamine D2 receptors in the basal ganglia and limbic portions of the forebrain. The earlier, less potent drugs, of which chlorpromazine is the prototype, cause more pronounced sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and cardiovascular toxicity from a combination of anticholinergic, antihistaminic, and anti–alpha-adrenergic effects. More potent agents (e.g., haloperidol) are safer, especially in older patients, because of their relative lack of these adverse effects. However, these more potent drugs are associated with a higher incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms, such as dystonias, akathisia, akinesia, and rigidity.

The high frequency of severe adverse reactions, poor compliance by patients, and the large number of patients with symptoms refractory to traditional antipsychotic agents prompted the development of new alternative agents. These “atypical” neuroleptic agents block serotonin to a greater extent than dopamine does, resulting in a low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects. Clozapine is particularly effective in patients who have not responded to other antipsychotic drugs.41 However, clozapine is expensive, has a side effect profile similar to that of the low-potency antipsychotic agents, and causes agranulocytosis in approximately 1% of patients.39 It is recommended only for the treatment of patients with refractory psychosis. Olanzapine, quetiapine, and the newest agent, aripiprazole, are similar to clozapine but have fewer side effects and less risk of agranulocytosis.38 Risperidone, another newer neuroleptic agent with improved effects on negative symptoms, has been found to be superior to haloperidol in several short-term trials.42–45 The most recent FDA-approved drug (2006), paliperidone (Invega), is the active metabolite of risperidone. Unfortunately, the expense and unavailability of these newer antipsychotic agents limit their utility for treatment of acute psychosis in the emergency department. Ziprasidone, risperidone, and quetiapine have been associated with QT interval prolongation similar to that seen with droperidol and haloperidol but have not yet been found to be associated with sudden cardiac death.46

Noncompliance with antipsychotic medication remains a leading cause of psychiatric hospitalization. Patients with recurrent psychotic relapses caused by noncompliance are candidates for treatment with long-acting injectable antipsychotic drugs, usually given every 2 weeks. Three such agents available in the United States are fluphenazine, risperidone, and haloperidol decanoate.47

Complications of Neuroleptic Drug Therapy

Acute dystonia, the most common adverse effect seen with neuroleptic agents, occurs in 1 to 5% of patients. This reaction is caused by a disruption of the dopaminergic-cholinergic balance in the nigrostriatal pathways of the basal ganglia, resulting in cholinergic dominance.48 Dystonic reactions, which can occur at any point during long-term therapy and up to 48 hours after administration of neuroleptics in the emergency department, involve the sudden onset of involuntary contraction of the muscles of the face, neck, or back. The patient may have protrusion of the tongue (buccolingual crisis), deviation of the head to one side (acute torticollis), sustained upward deviation of the eyes (oculogyric crisis), extreme arching of the back (opisthotonos), and rarely laryngospasm. These symptoms tend to fluctuate, decreasing with voluntary activity and increasing under emotional stress, which occasionally misleads emergency physicians to believe they are factitious.

Dystonic reactions should be treated with intramuscular or intravenous benztropine (Cogentin), 1 to 2 mg, or diphenhydramine (Benadryl), 25 to 50 mg, which usually results in immediate reversal of symptoms. Patients should receive oral therapy with the same medication for 48 to 72 hours to prevent recurrent symptoms.48

Akathisia

Akathisia is a state of motor restlessness characterized by a physical need to be moving constantly. It occurs most often in middle-aged patients during the first few months of therapy. Patients usually pace the room and express a sense of inner tension that is not relieved by activity. If asked, they do not want to be constantly moving but feel physically compelled to do so. This reaction can easily be mistaken for a decompensating psychosis, leading to a vicious circle in which more medication is given to treat a side effect caused by the same drug. This misdiagnosis can be avoided by carefully evaluating the patient for the exacerbation of positive psychotic symptoms, which are not increased by akathisia. Akathisia is treated with beta-blockers (e.g., propranolol, 30-60 mg/day) and anticholinergic drugs (e.g., benztropine, 1 mg twice to four times daily). A new potential agent for the treatment of akathisia is glycine, a nonessential amino acid that stimulates glutamatergic neurotransmission.49 In addition, if possible, the dosage of the antipsychotic agent should be lowered or replaced with another drug.

Tardive Dyskinesia

The reported prevalence of tardive dyskinesia ranges from 0.5 to 70%, with a mean of 24%.48 The incidence of the disorder appears to be directly related to the duration of treatment, total cumulative dosage, evidence of preexisting brain damage, and age of the patient. It is more common in elderly women and patients with associated mood disorders. For patients with mild symptoms, discontinuation or lowering of the dosage of antipsychotic agents, switching to a newer atypical neuroleptic agent, and cotreatment with benzodiazepines may reverse the symptoms. Patients with moderate to severe symptoms are difficult to treat, but some have variable degrees of improvement when they are treated with reserpine or tetrabenazine along with discontinuation of neuroleptic treatment.48

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a life-threatening complication of neuroleptic drug treatment that affects 0.5 to 1% of patients.50 It is seen with both typical and atypical neuroleptic agents and usually occurs in the first few weeks after initiation of treatment, but it can also be seen after a recent increase in drug dosage or after parenteral treatment with large doses of neuroleptic agents. NMS is characterized by high fever, severe muscle rigidity, altered consciousness, autonomic instability, and elevated serum creatine kinase levels and can be confused with serotonin syndrome. Additional complications can include respiratory failure, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hepatic and renal failure, coagulopathy, and cardiovascular collapse.

The pathophysiologic mechanism of NMS is not well understood, but it is thought to be related to dopamine depletion in the central nervous system leading to defective thermoregulation in the hypothalamus. Predisposing factors include exhaustion, dehydration, and the use of long-acting depot neuroleptics. Treatment consists of recognition and discontinuation of the neuroleptic agent, temperature reduction, rehydration with intravenous fluids, and general supportive measures. Dantrolene, a direct-acting muscle relaxant, should be used in severe cases. It can be administered by continuous rapid intravenous push at a minimum initial dose of 1 mg/kg, repeated until symptoms subside or up to a maximum cumulative dose of 10 mg/kg. For severe symptoms, dopamine agonists, such as bromocriptine, levodopa, and amantadine, have shown encouraging results. Because of early recognition and treatment, mortality rates with NMS have decreased from 30% to less than 10%.51

Disposition

A psychiatric short-procedure unit offers a cost-effective alternative to hospitalization.52 After stabilization, patients are moved from the emergency department to a separate treatment area, where they are treated for a period of 12 to 24 hours by a small staff of consultants.

References

1. Jones, P, Cannon, M. The new epidemiology of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21:1.

2. Tomlinson, WK. Schizophrenia: History of an illness. Psychiatr Med. 1990;8:1.

3. Tueth, MJ. Schizophrenia: Emil Kraepelin, Adolph Meyer, and beyond. J Emerg Med. 1995;13:805.

4. Lewis, G, et al. Schizophrenia and city life. Lancet. 1992;340:137.

5. Opler, LA, et al. Symptom profiles and homelessness in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1994;182:174.

6. Kropp, S, et al. Characteristics of psychiatric patients in the accident and emergency department (ED). Psychiatr Prax. 2007;34:72.

7. Schwab, SG, et al. Support for a chromosome 18p locus conferring susceptibility to functional psychoses in families with schizophrenia, by association and linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1139.

8. Michels, R, Morzuk, PM. Progress in psychiatry. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:552.

9. Lieberman, JA, et al. Serotonergic basis of antipsychotic drug effects in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:1099.

10. Tandon, R. Cholinergic aspects of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1999;37:7.

11. Tamminga, CA. Schizophrenia and glutamatergic transmission. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1998;12:21.

12. McGrath, JJ, et al. The neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia: A review of recent developments. Ann Med. 2003;35:86.

13. Harrison, PJ. The neuropathology of schizophrenia: A critical review of the data and their interpretation. Brain. 1999;122:593.

14. Crow, TJ, Harrington, CA. Etiopathogenesis and treatment of psychosis. Annu Rev Med. 1994;45:219.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

16. Olshaker, JS, et al. Medical clearance and screening of psychiatric patients in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:124.

17. Breslow, RE, Klinger, BI, Erickson, BJ. Acute intoxication and substance abuse among patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:183.

18. Elangovan, N, et al. Substance abuse among patients presenting at an inner-city psychiatric emergency room. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:782.

19. Dhossche, D, Rubinstein, J. Drug detection in a suburban psychiatric emergency room. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1996;8:59.

20. Tintinalli, JE, Peacock, FW, IV., Wright, MA. Emergency medical evaluation of psychiatric patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:859.

21. Henneman, PL, Mendoza, R, Lewis, RJ. Prospective evaluation of emergency department medical clearance. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:672.

22. Smith, ML. Atypical psychosis. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;4:895.

23. Hutto, B. Subtle psychiatric presentations of endocrine diseases. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21:905.

24. Frame, DS, Kercher, EE. Acute psychosis: Functional vs. organic. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1991;9:123.

25. Currier, GW, Trenton, A. Pharmacological treatment of psychotic agitation. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:777.

26. Hillard, JR. Emergency treatment of acute psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:57.

27. Battaglia, J, et al. Haloperidol, lorazepam, or both for psychotic agitation? A multicenter, prospective, double-blind, emergency department study. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:335.

28. Thomas, HA. Droperidol vs. haloperidol for chemical restraint of agitated and combative patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:407.

29. Richards, JR, Derlet, RW, Duncan, DR. Chemical restraint for the agitated patient in the emergency department: Lorazepam versus droperidol. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:567.

30. Richards, JR, Schneir, AB. Droperidol in the emergency department: Is it safe? J Emerg Med. 2003;24:441.

31. Chase, PB, Biros, MH. A retrospective review of the use and safety of droperidol in a large, high-risk, inner-city emergency department patient population. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1402.

32. Shale, JF, et al. A review of the safety and efficacy of droperidol for the rapid sedation of severely agitated and violent patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:500.

33. Freudenreich, O, et al. The evaluation and management of patients with first-episode schizophrenia: A selective, clinical review of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2007;15:189.

34. Daniel, DG, et al. Intramuscular ziprasidone 20 mg is effective in reducing acute agitation associated with psychosis: A double-blind randomized trial. Psychopharmacology. 2001;115:128.

35. Marco, C, Vaughan, J. Emergency management of agitation in schizophrenia. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:767.

36. Huang, T. Lorazepam and diazepam rapidly relieve catatonic signs in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:52.

37. Martel, M, et al. Management of acute undifferentiated agitation in the emergency department: A randomized double-blind trial of droperidol, ziprasidone, and midazolam. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1167.

38. Cain, JM. Schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:34.

39. Alvir, JM, et al. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: Incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:162.

40. Fleischhacker, WW. New developments in the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2003;64:105.

41. Breier, A, et al. Effects of clozapine on positive and negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:20.

42. Marder, SR, Meibach, RC. Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:825.

43. Tran, PV, et al. Double-blind comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:407.

44. Breier, AF, et al. Clozapine and risperidone in chronic schizophrenia: Effects on symptoms, parkinsonian side effects, and neuroendocrine response. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:294.

45. Leucht, S, et al. Efficacy and extrapyramidal side-effects of the new antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole compared to conventional antipsychotics and placebo: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Res. 1999;35:51.

46. Trenton, AJ, Currier, GW, Zwemer, FL. Fatalities associated with therapeutic use and overdose of atypical antipsychotics. CNS Drugs. 2003;17:307.

47. Davis, JM, et al. Depot antipsychotic drugs: Their place in therapy. Drugs. 1994;47:741.

48. Fernandez, HH, Friedman, JH. Classification and treatment of tardive syndromes. Neurologist. 2003;9:16.

49. Heresco-Levy, U, et al. Efficacy of high-dose glycine in the treatment of enduring negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:29.

50. Viejo, LF, et al. Risk factors in neuroleptic malignant syndrome: A case-control study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:45.

51. Caroff, SN, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome in the critical care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2609.

52. Mausbach, BT, et al. Reducing emergency medical service use in patients with chronic psychotic disorders: Results from the FAST intervention study. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:1.