CHAPTER 53 Thorax: overview and surface anatomy

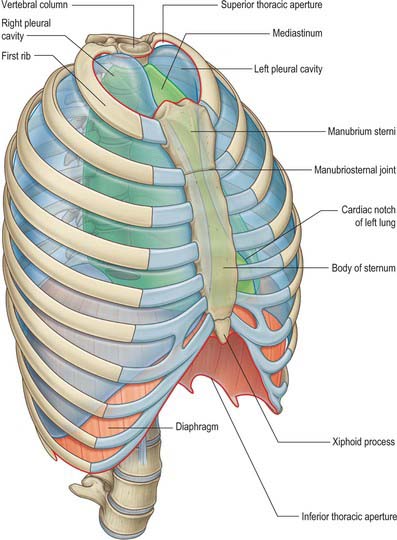

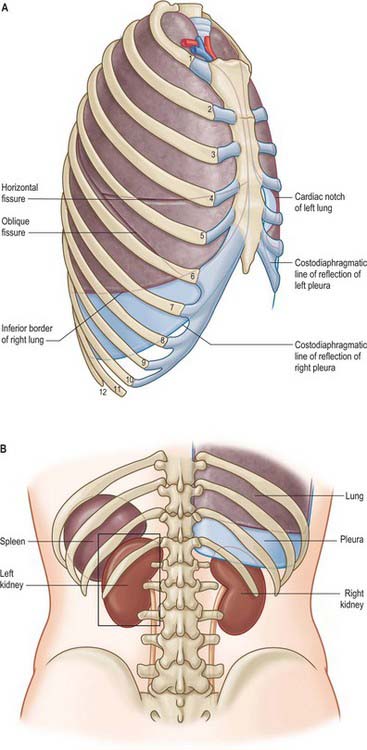

The thorax is the upper part of the trunk. It consists of an external musculoskeletal cage, the thoracic wall, and an internal cavity that contains the heart, lungs, oesophagus, trachea, thymus, the vagus and phrenic nerves and the right and left sympathetic trunks, the thoracic duct and major systemic and pulmonary blood vessels. Inferiorly the thorax is separated from the abdominal cavity by the diaphragm, superiorly it communicates with the neck and the upper limbs. The thoracic wall also offers protection to some of the abdominal viscera: the greater part of the liver lies under the right dome of the diaphragm; the stomach and spleen lie under the left dome of the diaphragm; the posterior aspects of the superior poles of the kidneys lie on the diaphragm and are anterior to the twelfth rib on the right, and to the eleventh and twelfth ribs on the left (Fig. 53.1).

Variations in thoracic dimensions and proportions are partly individual and also linked to age, sex and race. At birth, the transverse diameter is relatively less than it is in the adult, but adult proportions develop as walking begins. Thoracic capacity is less in females than it is in males, both absolutely and proportionately: the female sternum is shorter, the thoracic inlet more oblique, and the suprasternal notch is level with the third thoracic vertebra (whereas it is level with the second in males). In all individuals, the size of the thoracic cavity changes continuously, according to the movements of the ribs and diaphragm during respiration (see Ch. 58), and the degree of distension of the abdominal viscera.

MUSCULOSKELETAL FRAMEWORK

BONES AND JOINTS

The thoracic skeleton consists of twelve thoracic vertebrae and their intervening intervertebral discs (midline, posterior), twelve pairs of ribs and their costal cartilages (predominantly lateral) and the sternum (midline, anterior). When articulated, they form an irregularly shaped osteocartilaginous cylinder, reniform in horizontal section, which is narrow above, broad below, flattened anteroposteriorly and longer behind (see Fig. 54.7). Laterally the thoracic cage is convex and is formed by the ribs, and anteriorly it is slightly convex and is formed by the sternum and the distal parts of the ribs and their costal cartilages. The first seven pairs of ribs are connected to the sternum by costal cartilages, the costal cartilages of the eighth to tenth ribs usually join the superjacent cartilage, and the eleventh and twelfth ribs are free (floating) at their anterior ends. The posterolateral curvature of the ribs, from their vertebral ends to their angles, produces a deep internal groove, the paravertebral gutter, on either side of the vertebral column. The ribs and costal cartilages are separated by intercostal spaces, which are deeper anteriorly and between the upper ribs. Each space is occupied by three layers of flat muscles and their aponeuroses, neurovascular bundles and lymphatic channels.

MUSCLES

Intrinsic and extrinsic muscles

The intrinsic muscles of the chest wall are the intercostal muscles, subcostalis, transversus thoracis, levatores costarum, serratus posterior superior and serratus posterior inferior. The intercostal muscles occupy each of the intercostal spaces and are named according to their surface relations, i.e. external, internal and innermost. All except levatores costarum are innervated by the adjacent intercostal nerves derived from the ventral rami of the thoracic spinal nerves; levatores costarum are innervated by the dorsal rami of the thoracic spinal nerves. The intrinsic muscles can elevate or depress the ribs, and are active during respiration, particularly forced respiration: their primary action is believed to be to stiffen the chest wall, preventing paradoxical movement during inspiration (see Ch. 58).

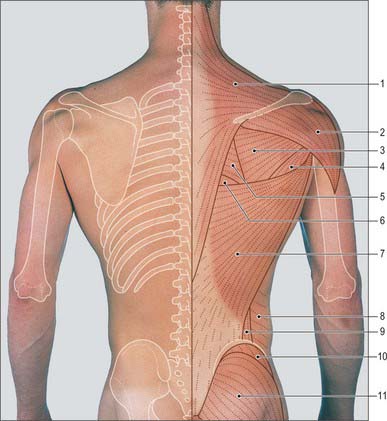

The skeletal framework of the thoracic wall provides extensive attachment sites for muscles associated functionally with the neck, abdomen, back, and upper limbs. Some of them (scalenes, infrahyoid strap muscles, sternocleidomastoid, serratus anterior, pectoralis major and minor, external and internal obliques, and rectus abdominis) function as accessory muscles of respiration and are usually active only during forced respiration; scalenus medius is active in quiet inspiration. Scalenus anterior, medius and posterior are described in Chapter 28. Trapezius, latissimus dorsi, rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, levator scapulae, pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, subclavius, serratus anterior, deltoid, subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and teres major are described in Chapter 46. Rectus abdominis, external oblique and internal oblique are described in Chapter 61.

Diaphragm

The diaphragm is a curved musculotendinous sheet attached to the circumference of the thoracic outlet and to the upper lumbar vertebrae. It forms the floor of the thoracic cavity, and separates it from the abdominal cavity (see Ch. 58). The diaphragm is relatively flat centrally and domed peripherally, rising higher on the right side than on the left, an asymmetry that reflects the relative densities of the underlying liver and gastric fundus respectively. From its highest point on each side the diaphragm slopes downward to its costal and vertebral attachments: this slope is most marked posteriorly, where the space between the diaphragm and the posterior wall of the thorax is very narrow.

Diaphragmatic openings

The inferior vena cava passes through an opening in the central tendon of the diaphragm to enter the right side of the mediastinum at the level of the eighth thoracic vertebra; the oesophagus passes through the muscular part of the diaphragm and enters the abdomen just to the left of the midline at the level of the tenth thoracic vertebra; and the descending thoracic aorta passes posterior to the diaphragm in the midline at the level of the twelfth thoracic vertebra (see Fig. 58.1A,B). Other structures which pass between the thorax and abdomen include the right and left vagi, phrenic and subcostal nerves, the thoracic duct, the sympathetic trunks and the thoracic splanchnic nerves, the right and left superior epigastric arteries and the hemiazygos and accessory hemiazygos veins.

THORACIC CAVITY

PLEURAL CAVITIES

The right and left pleural cavities are separate compartments on either side of the mediastinum. Each encloses a lung and its associated bronchial tree and vessels, nerves and lymphatics (see Ch. 57). The walls are formed by a serous membrane, the pleura, arranged as a closed sac. The outer layer of the sac, the parietal pleura, lines the corresponding half of the thoracic wall and covers much of the diaphragm and structures occupying the middle region of the thorax. The inner or visceral layer is more delicate and adheres closely to the pulmonary surface, following the interlobar fissures. The two layers are continuous with each other around the structures at the hila of the lungs. They remain in close, though sliding, contact at all phases of respiration. The potential space between them is the pleural cavity, which is maintained at a negative pressure by the inward elastic recoil of the lung and the outward pull of the chest wall. The lungs do not fill this space in quiet respiration, but move into recesses such as the costodiaphragmatic recess, which separates the costal and diaphragmatic pleura, in deep breathing.

MEDIASTINUM

The mediastinum lies between the right and left pleural sacs in and near the median sagittal plane of the chest (see Ch. 55). It extends from the sternum anteriorly to the vertebral column behind. A horizontal plane passing through the manubriosternal joint and the intervertebral disc between the fourth and fifth thoracic vertebrae separates the mediastinum into superior and inferior portions.

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

ARTERIAL SUPPLY

The skin of the thorax is supplied by direct cutaneous vessels and musculocutaneous perforators which reach the skin primarily via the intercostal muscles, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi and trapezius. Branches from the thoracoacromial axis, lateral thoracic, internal thoracic, anterior and posterior intercostal, thoracodorsal, transverse cervical, dorsal scapular and circumflex scapular arteries are the major contributing vessels (see Figs 42.4, 54.1, 54.2).

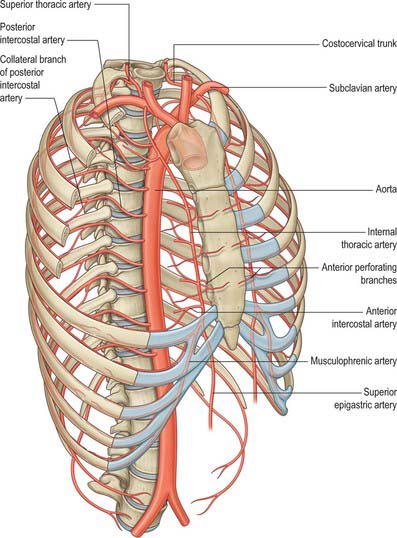

Muscles of the thoracic wall receive their blood supply from the internal thoracic artery (either directly or via the musculophrenic artery), the superior intercostal artery (from the costocervical trunk), superior thoracic artery (from the axillary artery), descending thoracic aorta, and the subcostal artery (Fig. 53.2). Additional contributions come from vessels that supply the proximal muscles of the upper limb, namely suprascapular, superficial cervical, thoracoacromial, lateral thoracic and subscapular arteries.

Fig. 53.2 Arteries of the thoracic wall and thoracic aorta.

(From Drake, Vogl, Mitchell, Tibbitts and Richardson 2008.)

The detailed arterial supply of the thoracic viscera is described with the viscera.

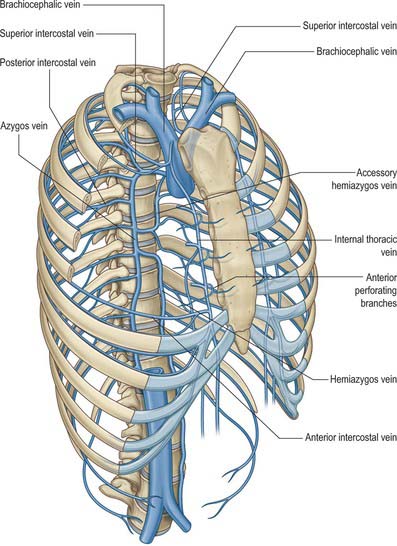

VENOUS DRAINAGE

The intercostal veins accompany the similarly named arteries in the intercostal spaces (Fig. 53.3). The small anterior intercostal veins are tributaries of the internal thoracic and musculophrenic veins: the internal thoracic veins drain into the appropriate brachiocephalic vein. The posterior intercostal veins drain backwards and most drain directly or indirectly into the azygos vein on the right and the hemiazygos or hemiazygos veins on the left. The azygos veins exhibit great variation in their origin, course, tributaries, anastomoses and termination.

INNERVATION

THORACIC SPINAL NERVES

There are twelve pairs of thoracic spinal nerves. The ventral rami, unlike their cervical and lumbar counterparts, have retained a largely segmental distribution to the body wall (see Figs 15.12, 54.3, 54.20). The upper eleven lie between the ribs (intercostal nerves), and the twelfth lies below the last rib (subcostal nerve). Each is connected with the adjoining ganglion of the sympathetic trunk by pre- and postganglionic branches (white and grey rami communicantes respectively). Intercostal nerves are distributed primarily to the thoracic and abdominal walls. The greater part of the first thoracic ventral ramus passes into the brachial plexus, together with a variable proportion of the second. The next four ventral supply only the thoracic wall, and the lower five supply both thoracic and abdominal walls. The subcostal nerve is distributed to the abdominal wall and the gluteal skin. Communicating branches link the intercostal nerves posteriorly in the intercostal spaces, and the lower five nerves communicate freely in the abdominal wall. Thoracic dorsal rami divide into medial and lateral branches that supply the intrinsic muscles of the back and the overlying postvertebral skin on a segmental basis (see Ch. 42).

The supraclavicular branches of C4 from the cervical plexus innervate the skin over the clavicle and may communicate with the anterior cutaneous branches of the second thoracic ventral ramus (see Ch. 28).

AUTONOMIC INNERVATION

Sympathetic trunks

The ganglionated sympathetic trunks lie anterior to the heads of the ribs; the ganglia are arranged segmentally (see Fig. 55.7). Preganglionic sympathetic axons originate from neurones in the lateral grey column of the spinal cord from T1 to L2, and leave the spinal cord with the corresponding ventral roots as white rami communicantes. Their targets vary. Some enter the sympathetic trunk, where they either synapse in their segmental ganglion or ascend or descend in the trunk to synapse in cervical or lumbar ganglia. Many of the preganglionic axons which originate in the lower thoracic spinal segments (T5–12) do not synapse locally but enter the abdominal cavity as the thoracic splanchnic nerves and synapse either in prevertebral ganglia, especially the coeliac ganglion, or around the medullary chromaffin cells of the suprarenal gland (see Ch. 72). Axons destined for the cervical ganglia are derived from preganglionic neurones in T1.

Vagus nerves in the thorax

Preganglionic parasympathetic fibres arise from neuronal cell bodies in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus in the medulla. Those destined for the thoracic viscera travel in the pulmonary, cardiac and oesophageal branches of the vagus and synapse in minute ganglia in the visceral walls. Axons traveling in cardiac branches join the cardiac plexuses and synapse in ganglia distributed over both atria: when stimulated, they slow the cardiac cycle (see Ch. 60). Pulmonary branches contain axons which relay in ganglia of the pulmonary plexuses and are motor (bronchoconstrictor) to the circular non-striated muscle fibres of the bronchi and bronchioles and secretomotor to the mucous glands of the respiratory epithelium.

Autonomic plexuses in the thorax

The cardiac plexus has a superficial component inferior to the aortic arch, lying between it and the pulmonary trunk, and a deep part between the aortic arch and tracheal bifurcation (see Ch. 56). The superficial part is formed by the cardiac branch of the left superior cervical sympathetic ganglion and the lower of the two cervical cardiac branches of the left vagus. The deep part is formed by the cardiac branches of the cervical and upper thoracic sympathetic ganglia and of the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves. The only cardiac nerves which do not join it are those that join the superficial part of the plexus. Branches from the cardiac plexuses also form the left and right coronary plexuses and the atrial plexuses.

The pulmonary plexuses are anterior and posterior to the other structures at the hila of the lungs (see Ch. 57). They are formed by cardiac branches from the second to fifth (or sixth) thoracic sympathetic ganglia and from the vagus, and from cervical sympathetic cardiac nerves. The left plexus also receives branches from the left recurrent laryngeal nerve.

The oesophageal plexus surrounds the oesophagus below the level of the lung roots (see Ch. 55). Vagal fibres either pass through the plexus or are given off directly by the vagus in the thorax. All fibres relay in the oesophageal wall and are motor to the smooth muscle in the lower oesophagus and secretomotor to mucous glands in the oesophageal mucosa. Vasomotor sympathetic fibres arise from the upper six thoracic spinal cord segments. Those from the upper segments synapse in cervical ganglia; postganglionic axons innervate the vessels of the cervical and upper thoracic oesophagus. Fibres from the lower segments pass directly to the oesophageal plexus or to the coeliac ganglion, where they synapse; postganglionic axons innervate the vessels of the distal oesophagus.

SURFACE ANATOMY

SKELETAL LANDMARKS

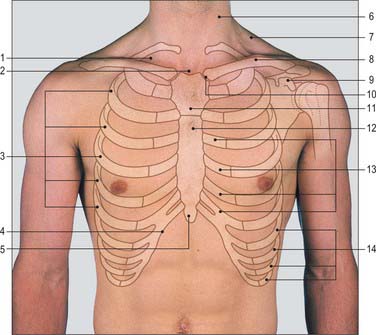

Anteriorly, the clavicle and sternoclavicular joint are not only palpable, but also visible in all but the most obese individuals (Fig. 53.4). The sternum can be felt throughout its length in the midline, but laterally it may be obscured by pectoralis major. The jugular notch (suprasternal notch) at the superior end of the sternum is easily found, and the trachea may be felt deep to it. The cartilaginous rings are usually palpable: by rolling one’s finger over the trachea, or by using two fingers within the notch, it is possible to assess whether the trachea is in the midline or deviated to one side. The jugular notch lies at the level of the junction between the second and third thoracic vertebrae. The manubriosternal angle is more pronounced in the male than in the female, and is felt at the junction of the manubrium with the body of the sternum. It is a particularly useful landmark because it indicates the medial ends of the second costal cartilages, and is level with the junction of the fourth and fifth thoracic vertebrae. The xiphisternal joint and xiphoid process may be felt at the inferior end of the sternum. The joint usually lies at the level of the ninth thoracic vertebra. Lateral to this, may be felt the costal margin, formed here by the anterior ends of the seventh costal cartilages. The rest of the costal margin is formed by the fused anterior ends of the eighth, ninth and tenth costal cartilages, whereas posteriorly the free ends of the eleventh and twelfth ribs may be palpable. In thin individuals, it is possible to palpate all the ribs from the first down to the costal margin. However, well-developed musculature or the female breast will obscure the ribs anteriorly and the shaft of the first rib (which lies predominantly behind the clavicle).

Posteriorly (Fig. 53.5), the spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae are easily palpable; the posterior angles of the ribs can be felt lateral to the spinous processes. The surface anatomy of the back and skeletal surface landmarks are described in Chapters 42 and 43.

INTRATHORACIC VISCERA

Anteriorly, the manubriosternal joint overlies the concavity of the aortic arch and marks the level at which the trachea bifurcates and the azygos vein enters the superior vena cava. The costal cartilages of the second ribs meet the sternum here, and so the joint offers an accurate point at which to start counting ribs. The transverse thoracic plane, which includes the sternal angle, demarcates the lower border of the superior mediastinum and the point at which the aortic arch receives the ascending aorta (anteriorly) and becomes the descending aorta (posteriorly). At this point, the right and left pleurae are in contact with each other; it is therefore a useful starting point when delineating the surface markings of the parietal pleura (Fig. 53.6A,B).

Heart

The surface projection of the anterior part of the atrioventricular groove is an oblique line that joins the sternal ends of the third left and sixth right costal cartilages and separates the atrial and ventricular areas. Although in different planes, the projections of the cardiac valves are also sited along or close to this line (see Fig. 56.6).

The sites of auscultation for the cardiac valves do not correspond directly to the surface anatomy of the valves, because the intensity of the sounds is influenced by direction of blood flow, which carries the sound with it. Thus, convenient sites at which to apply the stethoscope bell or diaphragm are: the sternal end of the second left intercostal space (pulmonary area); the sternal end of the second right intercostal space (aortic area); near the cardiac apex (mitral area); and over the left lower sternal border, at the level of the fifth intercostal spaces (tricuspid area) (see Fig. 56.6).

Great vessels

The aortic arch lies predominantly behind the manubrium sterni. Starting at the aortic valve (behind the lower border of the third left costal cartilage), the ascending aorta curves forwards, upwards and to the right, to become the aortic arch behind the right half of the manubrium at the level of the second right costal cartilage. It continues to ascend behind the right side of the manubrium sterni, arching over the transthoracic plane and descending such that the aortic knuckle protrudes just to the left of the manubrium sterni in the first intercostal space. The pulmonary trunk and tracheal bifurcation lie within its concavity. The brachiocephalic artery arises approximately behind the centre point of the manubrium and ascends to the right sternoclavicular joint. The superior vena cava descends predominantly behind, but also just to the right of, the right manubrial border and enters the right atrium at the level of the third right costal cartilage. The short right brachiocephalic vein descends almost vertically from behind the medial end of the clavicle just lateral to the right sternoclavicular junction, whereas the much longer left brachiocephalic vein passes almost horizontally behind the superior portion of the manubrium sterni. Both join behind the first right costal cartilage to form the superior vena cava, which descends as a band, 2 cm wide, along the right sternal margin, reaching the right atrium at the level of the third right costal cartilage.

Lungs and pleurae

Pleural reflections

Viewed from the back, the medial edge of the pleura may be followed along a line joining the transverse processes of the second to the twelfth thoracic vertebrae. It extends horizontally laterally, and crosses the twelfth and eleventh ribs to meet the tenth rib in the midaxillary line (Fig. 53.6A,B).