CHAPTER SEVEN THORACIC SPINE

INTRODUCTION

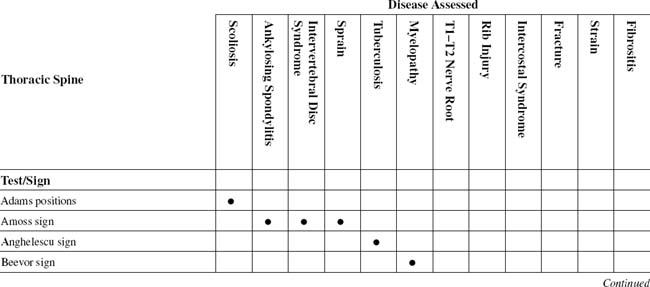

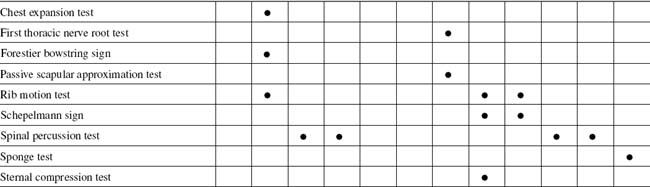

TABLE 7-2 THORACIC SPINE CROSS-REFERENCE TABLE BY SYNDROME OR TISSUE

| Ankylosing spondylitis |

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-1 THORACIC AREA PAIN

Diagnostic keys for thoracic area pain include the following:

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-2 MECHANICAL SPINAL SYNDROME CLASSIFICATIONS

Adapted from Hefford C: McKenzie classification of mechanical spinal pain: profile of syndromes and directions of preference, Man Ther 13(1):75–81, 2008.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-3 THORACIC SPINE

Stabilizing influences for the thoracic spine include the following:

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-4 THORACOLUMBAR SPINE

To assess range of motion of the thoracolumbar spine, the patient is directed to do the following:

ESSENTIAL MUSCLE FUNCTION ASSESSMENT

During the trunk extension test, the latissimus dorsi, quadratus lumborum, and trapezius assist back extensors. The head and neck extensor muscles and the hip extensors should be tested before the back extensors are tested (Fig. 7-7).

ESSENTIAL IMAGING

ADAMS POSITIONS

Assessment for Pathologic or Structural Scoliosis

Comment

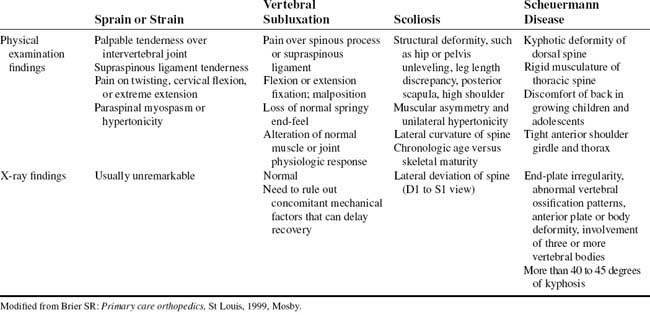

The spinal column centers the mass of the torso and head in a line along the vertical axis that falls through the pelvis. Disturbances of the spine, such as the curvatures associated with scoliosis, may significantly alter the normal balance and coordination of the spine (Table 7-3).

Scoliosis is also classified as either structural or nonstructural. Structural curves are fixed and nonflexible and fail to correct with side bending. Nonstructural curves, on the other hand, are flexible and readily correct with side bending. The Lenke Classification System helps examiners develop a more complete picture of the patient’s condition by understanding the scoliosis as multidimensional and considering it from more than one view. The Lenke classification method also gives more detailed shorthand for communicating about scoliosis in professional settings, using a widely understood set of criteria (Table 7-4).

|

| The Lenke Classification System is simple, accurate, and easy to reproduce and communicate between health care providers. It relies on measurements taken from standard radiographs (X-rays). In this method, the examiner evaluates X-rays of the patient from the front, the side, and in bending positions. Each scoliosis curve is then classified in three steps by the region of the spine, the degree or angle of the curve, and the relationship of the side-to-side curve to the sagittal plane. For example, many scoliosis curves affect the presence or absence of kyphosis, which is the outward or convex curve normally found in the upper back. In addition, each aspect of the curve is evaluated for its relative stiffness or flexibility. |

From Dr. Lawrence Lenke, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri. Available at: www.spinal-deformity-surgeon.com.

PROCEDURE

AMOSS SIGN

Assessment for Ankylosing Spondylitis, Severe Sprain, or Intervertebral Disc Syndrome

Comment

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), an ascending disease, affects the thoracic region after the lumbar. Patients with this condition experience back pain, but the anterolateral chest pain and the limited chest expansion bother them the most. In some patients, these symptoms may occur rather early in the life of the disease, but they usually become bothersome after 6 years of illness. Chest pain, which usually occurs during inspiration, and limited chest expansion are caused primarily by involvement of costovertebral and manubriosternal joints, as well as the costochondral junctions and the clavicular joints. The girdle-like restriction may cause a sense of anxiety and dyspnea, particularly during exertion. However, respiratory problems are surprisingly uncommon, although restricted ventilatory volumes are detected by pulmonary function studies (Table 7-5). Of course, should concomitant disease result in impaired diaphragmatic breathing, a problem is likely to develop.

TABLE 7-5 MODIFIED NEW YORK CRITERIA FOR ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS DIAGNOSIS

| Clinical criteria |

Adapted from Moll JMH: New criteria for the diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis, Scand J Rheum 16(suppl 65):12-24, 1987.

PROCEDURE

ANGHELESCU SIGN

Assessment for Tuberculosis of the Vertebrae or Other Destructive Processes of the Spine

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-7 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF TUBERCULOUS MENINGITIS

Adapted from Garcia-Monco JC: Central nervous system tuberculosis, Neurol Clin 17(4):737-759, 1999.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-8 PROBLEMS IN CONFIRMING THE CLINICAL SUSPICION OF TUBERCULOSIS MENINGITIS

Adapted from Garcia-Monco JC: Central nervous system tuberculosis, Neurol Clin 17(4):737-759, 1999.

PROCEDURE

BEEVOR SIGN

Assessment for Myelopathy Associated with the T10 Spinal Level

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-9 GUILLAIN-BARRÉ SYNDROME DISABILITY SCORE

Adapted from van Koningsveld R et al: A clinical prognostic scoring system for Guillain-Barre syndrome, Lancet Neurol 6(7):589–594, 2007.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-10 MEDICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL SUM SCORE

Adapted from van Koningsveld R et al: A clinical prognostic scoring system for Guillain-Barre syndrome, Lancet Neurol 6(7):589–594, 2007.

PROCEDURE

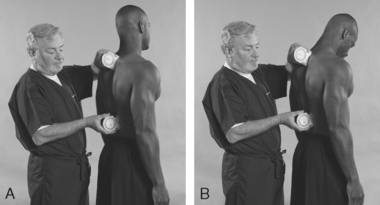

FIRST THORACIC NERVE ROOT TEST

Assessment for First or Second Thoracic Nerve Root Involvement

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-11 NERVOUS SYSTEM

The four components of the nervous system that refer pain or discomfort follow:

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-12 COMMON HISTORICAL AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS IN THORACIC INTERVERTEBRAL DISK HERNIATION

Adapted from Linscott MS, Heyborne R: Thoracic intervertebral disk herniation: a commonly missed diagnosis, J Emerg Med 32(3):235-238, 2007.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-13 PAIN REFERRAL

Pain referral rules are as follows:

PROCEDURE

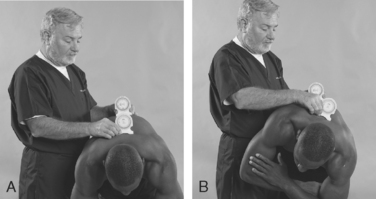

FORESTIER BOWSTRING SIGN

Assessment for Ankylosing Spondylitis

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-14 THORACIC KYPHOSIS

Patients with thoracic kyphosis are classified into the following two groups:

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

SCHEPELMANN SIGN

Assessment for Costal and Intercostal Tissue Integrity

Comment

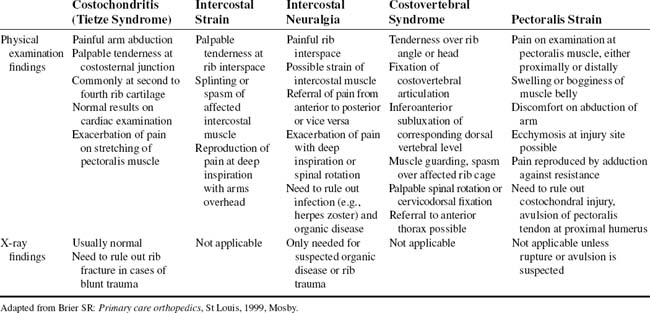

Any fixation or aberrant movement of the costovertebral articulations, or ribs, can have an impact on the synovial joints of the dorsal spine. The examiner rarely finds concomitant loss of joint play at the rib angle and corresponding vertebral motor unit. Experts have suggested that the rib cage may act as a splint to the thoracic spine. This splinting effect may prevent stresses placed directly on the midspine. In addition, it may be one of the reasons that thoracic disc herniations are less common. The fully developed ribs protect the underlying thoracic viscera while simultaneously providing attachment sites for a wide variety of muscles (Table 7-6).

| Region | Tissues |

|---|---|

| Superiorly | Sternocleidomastoid, sternohyoid, sternothyroid, and anterior, middle, and posterior scalene muscles |

| Anteriorly | Pectoralis major and minor muscles, mammary glands |

| Posteriorly | Serratus posterior superior and inferior, and deep back muscles; trapezius, rhomboid minor and major, scapula, and all muscles related to it reset against the thoracic cage |

| Laterally | Serratus anterior muscles |

| Inferiorly | Abdominal muscles attaching to thoracic cage (i.e., rectus abdominis, external and internal abdominal oblique, transverses abdominis) |

Adapted from Cramer GD, Darby SA: Basic and clinical anatomy of the spine, spinal cord, and ANS, St Louis, 1995, Mosby.

SPINAL PERCUSSION TEST

Assessment for Spinal Osseous and Paraspinal Soft-Tissue Integrity

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-15 MULTIPLE-LEVEL SPINAL FRACTURES

Three patterns of injury in multiple-level spinal fractures are:

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-16 THORACOLUMBAR FRACTURES

Thoracolumbar fracture classifications (based on three-column concepts) follow:

PROCEDURE

SPONGE TEST

Assessment for Acute Inflammatory Lesions of the Spine

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 7-17 FIBROMYALGIA TENDER POINT EXAMINATION PROTOCOL

Adapted from D’Arcy Y, McCarberg BH. New fibromyalgia pain management recommendations, J Nurs Pract 1(4):218–225, 2005.

Palpation technique

Patient instruction

Comment

Common findings on examination include muscle spasm or taut bands of muscle, sometimes called nodules by patients; skin sensitivity, in the form of skin roll tenderness of dermatographism; or purplish mottling of the skin, especially of the legs after exposure to the cold. Myofascial pain syndromes also overlap with fibromyalgia (Table 7-7). The relationship of trigger points and tender points is not clear. The location of the trigger point is deep within the muscle belly. Trigger points result in decreased muscle stretch and pain with contraction. A twitch response (or jump sign), pathognomonic of an active trigger point, is a visible or palpable contraction of the muscle produced by a rapid snap of the examining finger on the taut band of muscle. A characteristic referred pain pattern is present.

TABLE 7-7 MISDIAGNOSES THAT MAY BE GIVEN TO PATIENTS WHO EVENTUALLY ARE FOUND TO HAVE THE FIBROMYALGIA SYNDROME

From Kelley WN et al: Textbook of rheumatology, ed 5, Philadelphia, 1997, WB Saunders.

STERNAL COMPRESSION TEST

Assessment for Costal Structure Fracture

Comment

Also known as Tietze syndrome, costochondritis is an inflammation of the rib cartilage at the costosternal junction. The differential diagnosis includes angina pectoris, intercostal strain and neuralgia, rib subluxation, and, in cases of substantial trauma, rib fracture. The patient with costochondritis complains of point tenderness over one or two rib heads or costal junctions lateral to the sternum (Table 7-8). Symptoms are most commonly localized to the second, third, or fourth costochondral junctions. Abduction of the arm reproduces the patient’s pain, which may radiate down the arm. Acute inflammation causes discomfort or pain on deep inspiration as the rib cage expands. Bogginess or swelling over the costal cartilage is possible but does not always occur.