CHAPTER 95 Thoracic Aortitis

Aortitis is often characterized by inflammation of the media and adventitia.1 Aortitis has many causes and may be related to autoimmune diseases or noninfectious causes as well as infection by microorganisms. Aortitis belongs to the group of diseases collectively known as the large-vessel vasculitides, as defined by the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the classification of systemic vasculitides.2 Regardless of the source, inflammation of the aorta often results in dilation of the aortic root and aortic insufficiency. As a consequence, aortic valve replacement with aortic root reconstruction is often needed. It can be divided into an acute inflammatory phase and a chronic fibrotic phase.

Classification can be based on whether the aortitis is inflammatory. Other classification systems are based on whether the cause is associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. The exact cause is often difficult to define with certainty (Table 95-1).

TABLE 95-1 Classification of Aortitis

| Infectious | Noninfectious |

|---|---|

| Syphilis |

Nonspecific aortic inflammation can also be seen in atherosclerosis. Because assessment of the vessel wall is critical in these patients, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or computed tomographic angiography (CTA) is preferred to conventional angiography. In general, inflammatory aortitis tends to affect the thoracic aorta rather than the abdominal aorta, whereas atherosclerosis affects the abdominal aorta.3

The more common diseases are discussed in this chapter.

TAKAYASU ARTERITIS

Definition

Takayasu arteritis was first described in 1908 by a Japanese ophthalmologist. This is a chronic vasculitis of unknown etiology affecting the aorta and its primary branches that can progress to ischemia or occlusion. The inflammation causes thickening of the walls of the affected arteries. The proximal aorta may become dilated secondary to inflammatory injury. Narrowings and occlusions are more common, but dilation of involved portions of the arteries can also result in myriad symptoms. Aneurysmal disease occurs in as many as 20% of patients,4 but mostly in the descending thoracic aorta (Table 95-2).

TABLE 95-2 Classification of Takayasu Arteritis by the American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria*

* If three of six criteria are met, patients are said to have Takayasu arteritis.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The majority of reported cases are in Asian patients, but there is a worldwide distribution. Women are affected in 80% to 90% of cases, with an age at onset between 10 and 40 years. In Japan, up to 150 cases occur per year,5 whereas there are about 1 to 3 new cases per year per million in the United States and Europe.6

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Usual presenting symptoms are systemic or constitutional—fatigue, weakness, arthralgias, weight loss, and low-grade fever—probably secondary to released cytokines. Vascular symptoms are rare at presentation; when they do develop, it is secondary to dilation or stenosis of the affected vessels. Classically, the disease is characterized by stenosis, but the incidence of aneurysmal lesions is increasing (30% to 50%).7 Patients may present in heart failure secondary to aortic dilation and regurgitation. Late-phase symptoms include diminished or absent pulses, bruits, hypertension, and heart failure (Fig. 95-1). Dissection is possible, but giant cell arteritis has a higher incidence.

Subclavian artery involvement is very common and often results in a blood pressure difference between the arms of more than 10 mm Hg. Lesions proximal to the vertebral artery may result in amaurosis fugax and subclavian steal. Up to 50% of patients have involvement of the pulmonary arteries.8 Pulmonary artery involvement can give rise to chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and pulmonary hypertension,9 but pulmonary function is generally not compromised despite extensive involvement, although unilateral pulmonary artery occlusion has been reported.10 Most frequently affected arteries apart from the aorta are subclavian (90%), carotid (45%), vertebral (25%), and renal (20%).11 Angina secondary to coronary ostial narrowing or coronary involvement is also possible. Affected arteries need to have vasa vasorum and are thus muscular, a feature lacking in peripheral arteries, which explains their lack of involvement in this condition. Patients may also present with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and skin lesions such as erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum.

Imaging Techniques and Findings

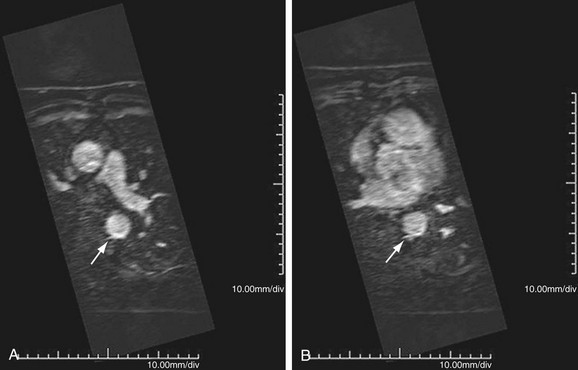

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography can detect perivasculitis, a rim of soft tissue around a great vessel, hypoechoic on ultrasound examination. One problem is that wall thickening may be indistinguishable from atherosclerotic plaque (Fig. 95-2). Intravascular ultrasound may detect subtle wall changes not seen on other techniques.

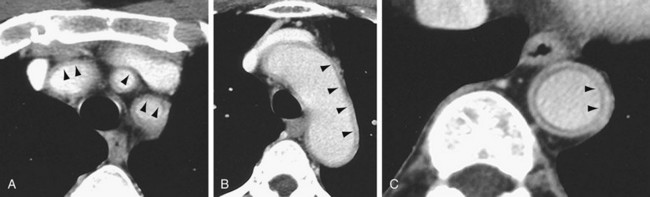

Computed Tomography

CT is usually the preferred initial examination; one can see mural calcification, and early disease detection portends a better prognosis. CT is good for detection and surveillance of arterial mural thickening, which decreases after steroid treatment. Typically, a double-ring pattern (poorly enhancing ring centrally, with a well-enhancing outside ring) can be seen. Perivasculitis, a rim of soft tissue around a great vessel that is hypodense on CT (vessel wall edema; Fig. 95-3), can also be detected. CT can also assess aortic or aortic branch vessel stenoses. The downside is ionizing radiation, especially in follow-up scans, as well as the need for iodinated contrast material, but it is a fast technique.

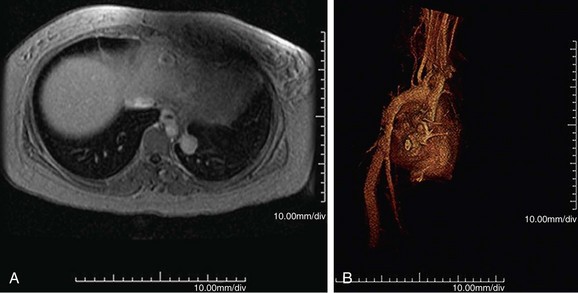

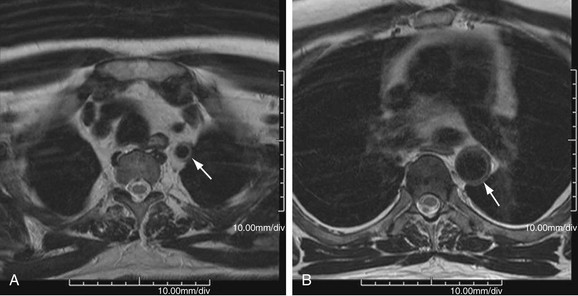

Magnetic Resonance

MR can detect mural thickening. It can also detect perivasculitis, a rim of soft tissue around a great vessel, along with aortic valvular thickening and pericardial effusion. Wall enhancement can be seen as an indicator of disease activity, secondary to edema and inflammation. Mural edema is seen as elevated T2 signal. Studies have shown reduced wall enhancement on follow-up, presumably secondary to reduced inflammation.12 Three-dimensional MRA does have decreased sensitivity for small vessels in comparison with conventional angiography (Figs. 95-4 and 95-5). One can do cine sequences to detect aortic regurgitation. Maximum intensity projection images should be used with caution because they can exaggerate the degree of vascular stenoses. Whereas MR is a longer examination, it benefits from its lack of ionizing radiation exposure, a feature preferable for long-term surveillance of Takayasu arteritis, which typically affects younger women.

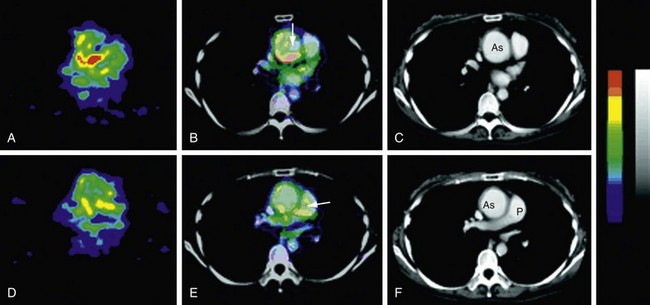

Nuclear Medicine/Positron Emission Tomography

Increased uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in regions of the aorta corresponds to abnormal regions on MRI.13 Positron emission tomography (PET) should be able to distinguish mural thickening secondary to active inflammation from scar formation and can be used to assess response to treatment (Fig. 95-6).

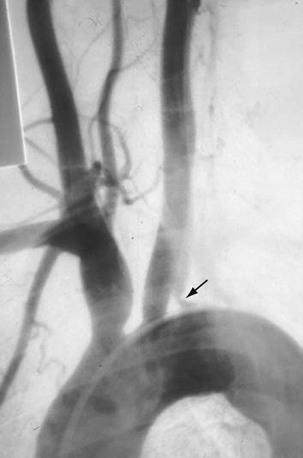

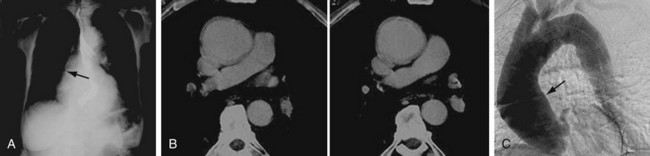

Angiography

Angiography is the gold standard for evaluation of Takayasu arteritis. The examination must evaluate the thoracic and abdominal aorta; findings are most commonly seen in the aorta and its primary branches. Early changes, such as arterial wall thickening, cannot be well assessed. In the late phase, one primarily sees smooth-walled, tapered, or focally narrowed areas, usually involving the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta and the subclavian, common carotid, and renal arteries (Fig. 95-7). Late-phase dilation can be seen in the ascending aorta and right-sided brachiocephalic artery, but the walls are generally smooth, differentiating this from atherosclerotic aneurysm. Collaterals may be present as stenotic disease can be chronic. Whereas angiography can lead to angioplasty or stenting, it rarely leads to biopsy because central arteries are being imaged. Pulmonary artery evaluation is recommended only in those with pulmonary hypertension.

Synopsis of Treatment Options

Surgical/Interventional

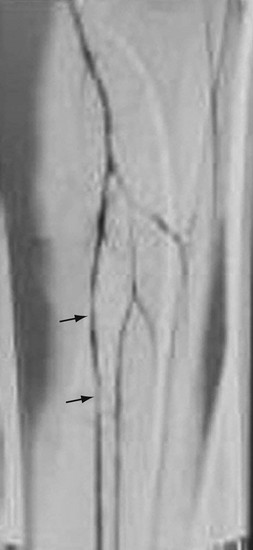

Bypass grafts may also be used in patients with severe stenosis or occlusion of the aorta (Fig. 95-8).

KEY POINTS

The main differential is giant cell aortitis, which can be ruled out by biopsy and the features in Table 95-3.

The main differential is giant cell aortitis, which can be ruled out by biopsy and the features in Table 95-3.TABLE 95-3 Differential Characteristics of Takayasu Arteritis Versus Giant Cell Arteritis

| Finding | Takayasu Arteritis | Giant Cell Arteritis |

|---|---|---|

| Female-to-male ratio | 7 : 1 | 3 : 2 |

| Age at onset | <40 years | >50 years |

| Ethnicity | Asian | European |

| Histopathology | Granulomatous inflammation | Granulomatous inflammation |

| Primary vessels involved | Aorta and branches | External carotid artery branches |

| Course | Chronic | Self-limited |

| Response to steroids | Excellent | Excellent |

| Surgical intervention | Common | Rare |

Modified from Hunder GG. Clinical features and diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis. UpToDate 2007.

GIANT CELL ARTERITIS

Definition

Giant cell arteritis, also known as temporal arteritis, is a chronic systemic panarteritis predominantly seen in elderly patents and affecting mainly cranial arteries. It affects large and medium-sized arteries, usually the cranial branches of arteries originating from the aortic arch and especially the temporal artery. Patients are at high risk for blindness; ischemic optic retinopathy develops in 20% to 50% of patients. Vision loss is often irreversible (Table 95-4). The etiology is unknown, but it may be autoimmune or secondary to infection; 10% to 15% of those with temporal artery involvement have aortic disease and often polymyalgia rheumatica.14 The median time to development of aortic aneurysm after diagnosis of giant cell arteritis is 5.8 years.15

TABLE 95-4 The American College of Rheumatology Criteria (1990) for the Diagnosis of Giant Cell Arteritis

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Incidence in the United States is 15 to 30 cases per year per 100,000 in those older than 50 years.16 In northern European countries, the annual incidence is more than 50 cases per 100,000.17 Sex predilection is in women, especially of northern European descent, with a 2 : 1 ratio of women to men. The mean age at presentation is 72 years, and it is essentially never seen in the age group younger than 50 years.18 A higher incidence is seen in Scandinavian countries.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Systemic symptoms are a common presentation. Localized temporal headache of new onset is seen in at least two thirds of patients. Tenderness and decreased pulse of the temporal artery are other common signs. Presentation is usually a fever of unknown origin; 50% of patients suffer from jaw claudication.19 A variety of visual symptoms can also occur, usually heralded by amaurosis fugax. Symptoms suggestive of aortic involvement are claudication of the upper or lower extremities, paresthesias, Raynaud phenomenon, abdominal angina, coronary ischemia, transient ischemic attacks, seizures, and aortic arch and great vessel steal phenomena. Aortic aneurysms with aortic regurgitation or dissection are possible. Dissection is more frequent with giant cell arteritis than with Takayasu arteritis. Polymyalgia rheumatica also occurs in 40% to 50% of patients.19 Jaw claudication in patients older than 50 years is highly specific but only 40% to 50% sensitive for giant cell arteritis.20 Giant cell arteritis is much less common in African Americans, and it affects women twice as commonly as men. Most patients present after the sixth decade, with a peak incidence between 60 and 80 years of age. Eighty-eight percent of large-vessel involvement occurs in women,21 and large-vessel involvement sometimes occurs years after diagnosis and treatment of giant cell arteritis. Patients can also present with abdominal aortic involvement, resulting in abdominal aortic aneurysm and intestinal infarction.

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Computed Tomography

Aortic aneurysms or dissection may be detected, although these are seen in only 15% of patients. CT can discern vessel wall thickness and lumen configuration, with the ability to assess wall enhancement as a measure of inflammation and edema. Long, smooth, tapering stenoses with areas of dilation may also be seen in subclavian, axillary, and brachial arteries. CT may be useful in patients with multiple cranial infarcts for evaluation of the arteries (Fig. 95-9).

Magnetic Resonance

MR is the study of choice, especially for diagnosis of large-vessel giant cell arteritis. MR can also identify regional temporal artery involvement with edema or enhancement, thereby guiding biopsy. Disease activity and response to treatment can also be observed, probably secondary to vessel wall edema, a sign of early inflammatory change (Fig. 95-10). Aortic aneurysms or dissection may be seen, although these are detected in only 15% of patients. MR can discern vessel wall thickness and lumen configuration, with the ability to assess wall enhancement as a measure of inflammation and edema (Fig. 95-11). Long, smooth, tapering stenoses with areas of dilation may also be seen in subclavian, axillary, and brachial arteries.

Angiography

Angiography is seldom used for diagnosis. Aortic root dilation, aortic regurgitation, and dissection as well as stenosis may be seen. Long, smooth, tapering stenoses with areas of dilation may also be seen in subclavian, axillary, and brachial arteries as well as in cerebral arteries (Fig. 95-12). It is sensitive but not specific. It can be used to measure intravascular blood pressures distal to stenoses, especially if there is four-limb involvement with the disease.

Synopsis of Treatment Options

Surgical/Interventional

Temporal artery biopsy is suggested in all cases of suspected giant cell arteritis, but the negative predictive value is at best 90%.22

SYPHILITIC AORTITIS

Definition

Syphilitic aortitis is now exceedingly rare in developed countries, but it once accounted for 5% to 10% of all cardiovascular deaths. However, with the increase in sexually transmitted diseases worldwide, the incidence may increase in the future. Among untreated patients, aortitis occurs in up to 70% to 80%.23 Cardiac complications usually occur in 10% of untreated cases. The latent period is 5 to 40 years, with disease usually occurring between 10 and 25 years (Table 95-5).

TABLE 95-5 Syphilitic Manifestations in Cardiovascular Disease

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Patients usually present with a combination of the aforementioned syphilitic complications, and syphilitic aortitis without aneurysm is uncommon. The aneurysms occur in the ascending aorta (47%), transverse arch (24%), abdominal aorta (7%), descending arch (5%), descending thoracic aorta (5%), multiple sites (4%), and sinus of Valsalva (<1%).24 Commonly, syphilitic aortitis involves the sinotubular junction and also the sinuses of Valsalva, a feature different from Takayasu arteritis. Coronary ostial lesions are seen in 20% to 25% of patients with syphilitic aortitis but in only 0.1% of patients with coronary artery disease.25 Dissection and intramural hematoma are rare. The aortitis usually involves the proximal aorta, only occasionally extending below the renal arteries.1

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

The classic tree bark appearance is shared with other forms of aortitis, notably Takayasu arteritis.26 On plain film, one may see a dense shadow, widening, and calcification of the aortic arch or possibly eggshell calcification outlining the aortic aneurysm. Calcification usually involves the ascending aorta (Fig. 95-13A).

Differential Diagnosis for Thoracic Aortitis

From Imaging Findings (Mural Thickening and Luminal Stenosis or Aneurysm)

Arend WP, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1129-1134.

Gravanis MB. Giant cell arteritis and Takayasu aortitis: Morphologic, pathogenetic and etiologic factors. Int J Cardiol. 2000;1:S21-S33.

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al. Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:187-192.

Paget SA, Leibowitz E Giant cell arteritis Available at http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic2241.htm Accessed May 21, 2008

Tavora F, Burke A. Review of isolated ascending aortitis: differential diagnosis, including syphilitic, Takayasu’s and giant cell aortitis. Pathology. 2006;38:302-308.

1 Tavora F, Burke A. Review of isolated ascending aortitis: differential diagnosis, including syphilitic, Takayasu’s and giant cell aortitis. Pathology. 2006;38:302-308.

2 Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al. Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:187-192.

3 Rojo-Leyva E, Ratliff NB, Cosgrove DM, Hoffman GS. Study of 52 patients with idiopathic aortitis from a cohort of 1204 surgical cases. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:901-907.

4 Weidner N. Giant cell vasculitides. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2001;18:24-33.

5 Koide K. Takayasu arteritis in Japan. Heart Vessels. 1992;7:48.

6 Arend WP, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1129-1134.

7 Hotchi M. Pathological studies on Takayasu arteritis. Heart Vessels Suppl. 1992;7:11-17.

8 Nakabayashi K, Kurata N, Nangi N, et al. Pulmonary artery involvement as first manifestation in three cases of Takayasu arteritis. Int J Cardiol. 1996;54:S177.

9 Kerr GS, Hallahan CW, Giordano J, et al. Takayasu arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:919.

10 Suzuki Y, Konishi K, Hisada K. Radioisotope lung scanning in Takayasu’s arteritis. Radiology. 1973;109:133-136.

11 Shelhamer JH, Volkman DJ, Parillo JE, et al. Takayasu’s arteritis and its therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:121-126.

12 Johnston SL, Lock RJ, Gompels MM. Takayasu arteritis: a review. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:481-486.

13 Meller J, Strutz F, Siefker U, et al. Early diagnosis and follow up of aortitis with 18F FDG PET and MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:730-736.

14 Levine SM, Hellman DB. Giant cell arteritis. Curr Opin Rhematol. 2002;14:3-10.

15 Evans JM, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG. Increased incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection in giant cell (temporal) arteritis: a population based study. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:502-507.

16 Huston KA, Hunder GG, Lie JT, et al. Temporal arteritis: a 25-year epidemiologic, clinical and pathologic study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:162-167.

17 Roque MR, Roque BL, Miserocchi E, Foster CS Giant cell arteritis Available at http://www.emedicine.com/OPH/topic254.htm Accessed May 21, 2008

18 Smetana GW, Shmerling RH. Does this patient have temporal arteritis? JAMA. 2002;287:92.

19 Hunder GG. Clinical manifestations of giant cell (temporal) arteritis. UpToDate. 2007. Available at http://www.uptodate.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=vasculit/2816&selectedTitle=1~150&source=search_result Accessed May 21, 2008

20 Goodwin JS. Progress in gerontology: polymyalgia rheumatica and temporal arteritis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:515-525.

21 Paget SA, Leibowitz E Giant cell arteritis Available at http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic2241.htm Accessed May 21, 2008

22 Hall S, Persellin S, Lie JT, et al. The therapeutic impact of temporal artery biopsy. Lancet. 1983;2:1217.

23 Jackman JD, Radolf JD. Cardiovascular syphilis. Am J Med. 1989;87:425-433.

24 Heggtveit HA. Syphilitic aortitis. A clinicopathologic autopsy study of 100 cases 1950-1960. Circulation. 1964;29:346-355.

25 Yamanaka O, Hobbs RE. Solitary ostial coronary artery stenosis. Jpn Circ J. 1993;57:404-410.

26 Gravanis MB. Giant cell arteritis and Takayasu aortitis: Morphologic, pathogenetic and etiologic factors. Int J Cardiol. 2000;1:S21-S33.

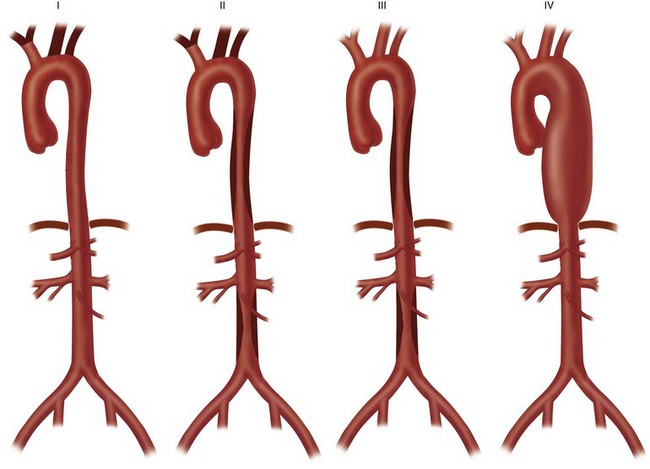

FIGURE 95-1

FIGURE 95-1

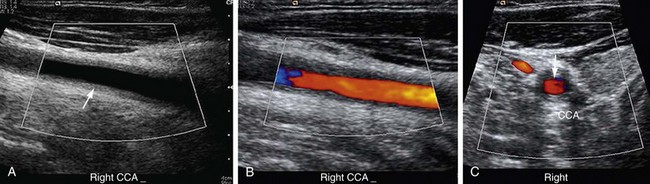

FIGURE 95-2

FIGURE 95-2

FIGURE 95-3

FIGURE 95-3

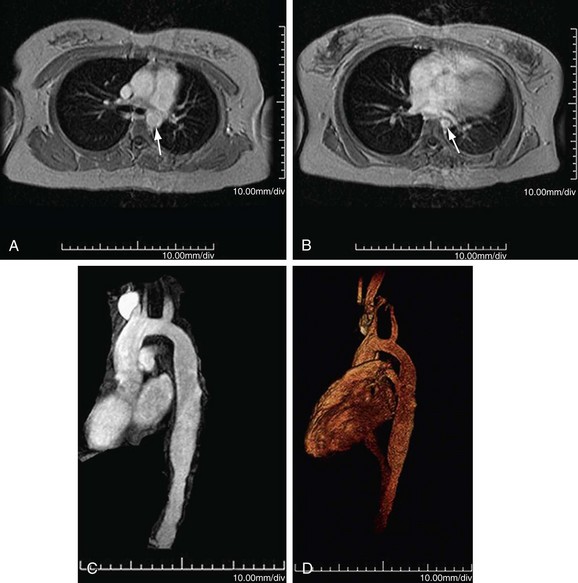

FIGURE 95-4

FIGURE 95-4

FIGURE 95-5

FIGURE 95-5

FIGURE 95-6

FIGURE 95-6

FIGURE 95-7

FIGURE 95-7

FIGURE 95-8

FIGURE 95-8

FIGURE 95-9

FIGURE 95-9

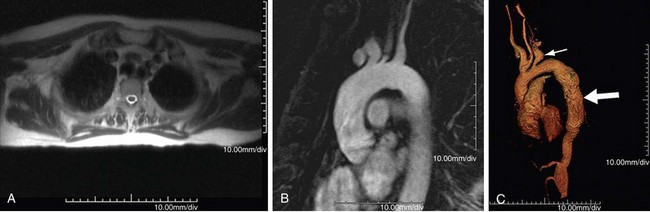

FIGURE 95-10

FIGURE 95-10

FIGURE 95-11

FIGURE 95-11

FIGURE 95-12

FIGURE 95-12

FIGURE 95-13

FIGURE 95-13

FIGURE 95-14

FIGURE 95-14