CHAPTER 64 Therapeutic Injections for the Treatment of Axial Neck Pain and Cervicogenic Headaches

INTRODUCTION

The treatment of chronic neck pain remains one of the most challenging problems pain management specialists are confronted with. Defined as continuous pain persisting for more than 6 months, an estimated 16–22% of adults suffer from chronic neck pain, with the condition having a higher prevalence in women than men.1,2 Among patients with chronic neck pain, approximately 30% report a history of neck injury, which is most commonly the result of a motor vehicle accident.1

Although neck pain is by definition perceived in the region of the body bounded laterally by the lateral margins of the neck, superiorly by the superior nuchal line and inferiorly by a line transecting the T1 spinous process,3 this does not presuppose it is caused by pathology in this area. Pain in the neck may be referred from visceral and somatic structures in the thorax, or even extremities (Table 64.1). Similarly, pathology in the neck may lead to symptoms elsewhere in the body, such as a herniated cervical disc causing pain in an arm, or upper cervical spine disease causing pain in the occiput. The latter scenario is particularly relevant, as cervicogenic headaches affect 0.4–2.5% of the general population, and 15–20% of chronic headache sufferers.4 The first attempt at setting guidelines for the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache was made in 1990 by Sjaastad et al.5 Since then, the diagnostic criteria have been updated, with the major change being that an analgesic response to anesthetic blocks in the neck is now obligatory.6 Thus, this chapter focuses on the use of interventional blocks in the cervical spine to treat axial neck pain and cervicogenic headaches.

| INFECTIOUS | |

| Osteomyelitis | |

| Epidural abscess | |

| Septic arthritis | |

| Discitis | |

| Meningitis | |

| Pharyngitis | |

| Tonsillitis | |

| Mumps, parotiditis | |

| Tuberculous spondylitis | |

| Lymphadenitis | |

| VASCULAR | |

| Vertebral artery aneurysm | |

| Carotid body tumor | |

| Inflamed thyroglossal duct | |

| Subclavian artery aneurysm | |

| REFERRED PAIN FROM THE THORAX | |

| Esophageal pathology (esophagitis, inflamed diverticulum, etc.) | |

| Thyroid pathology (thyroiditis, thyroid cystadenoma, etc.) | |

| Mediastinal pain (pneumomediastinum, mediastinitis, etc.) | |

| Angina | |

| MALIGNANT | |

| Primary or metastatic tumors of the cervical spine | |

| Spinal cord tumors | |

| Pancoast’s tumor | |

| Bronchial tumors | |

| RHEUMATOLOGIC | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | |

| Osteoarthritis | |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | |

| Crystal arthropathies including gout | |

| Fibromyalgia | |

| MUSCLE AND OTHER SOFT TISSUE DISORDERS | |

| Tendonitis | |

| Myofascial pain syndrome | |

| Soft tissue injuries | |

| Cervical strain | |

| Anterior scalene syndrome | |

| Pectoralis minor syndrome | |

| Torticollis | |

| Viral myalgia | |

| Soft tissue calcium deposits and the 1st or 2nd cervical vertebrae | |

| BONY PATHOLOGY | |

| Hyoid bone syndrome | |

| Cervical rib | |

| Paget’s disease | |

| Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament or longus collis | |

| Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) | |

| Fractures | |

| Spondylosis | |

| NEUROLOGIC | |

| Thoracic outlet syndrome | |

| Nerve injuries | |

| Greater occipital neuralgia | |

| Myelopathy | |

| Radiculopathy | |

| Syringomyelia | |

| Arnold–Chiari malformation | |

| Cervical acute herpes zoster or postherpetic neuralgia | |

| TRAUMATIC | |

| Epidural hematoma | |

| Dislocations | |

| Subluxation | |

| Acute herniated disc | |

| Ligamentous injury | |

| Cervical strain | |

| MISCELLANEOUS | |

| Branchial cleft remnant | |

| Psychogenic pain | |

| Postural disorders | |

| Synovial cyst | |

| Temporomandibular disorder | |

ATLANTO-OCCIPITAL JOINT BLOCKS

Anatomy and function

The articulations of the occipital-atlanto-axial complex are among the most complex in the human body. The primary function of the AO joint is flexion and extension in a sagittal plane (i.e. nodding of the head). While flexion at the AO joint is usually limited to around 10°, the degree of extension is considerably greater, approaching 25°.7 The range of motion in the anteroposterior plane is generally restricted to less than 20° rotation. The innervation of the AO joint is from the ventral ramus of C1, with the second dorsal cervical nerve supplying the AO synovial space.8,9

Mechanisms of injury

Perhaps owing to the relative weight of the cranial contents and the stress induced by frequent movements of the head, atlanto-occipital mediated joint pain has been described in a variety of different inflammatory diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis.10,11 Trauma is another common cause of AO joint pain, with hyperextension of the skull, with or without damage to the tectorial membrane, being the proposed mechanism of action. Interestingly, restriction of normal articular motion is also hypothesized to result in pain emanating from the AO joint.12 Proposed etiologies of this type of injury include intra-articular adhesions, capsular scarring, and localized muscle hypertonicity.11

Clinical presentation

The presentation of patients with AO joint pain is protean, with no known pathognomonic features.13 The International Headache Society’s (IHS) diagnostic criteria for cervicogenic headache include:6

In a study assessing the response to lateral AO joint injections in five asymptomatic volunteers, Dreyfuss et al. found considerable variability in the provoked pain patterns, with the most inferior area of pain approximating the C5 vertebral level, and the most superior area extending almost to the vertex of the skull.8 In one patient, only temporal pain was produced. Most subjects tended to have pain limited to the upper neck and suboccipital regions. The induced pain was typically characterized as being ‘dull,’ ‘aching,’ or ‘pressure-like,’ and unilateral in distribution. In a study by Fukui et al., whose aim was to determine the pain referral patterns for all levels of cervical zygapophyseal joint injections, in the 10 patients with neck and occipital pain who underwent lateral AO joint blocks, pain was referred into the ipsilateral upper posterolateral cervical region in all cases, and into the occipital area in 30% of patients.14

Outcome studies

While it is widely acknowledged that the AO joint can be a source of head and/or axial neck pain, there is scant evidence to support the therapeutic use of intra-articular joint blocks. In a paper by Dreyfuss et al., they reported three patients with upper neck pain and/or occipital headaches who obtained complete relief after local anesthetic and steroid injections of the AO joints.15 In one patient, two injections were needed. However, in two of the patients, atlantoaxial (AA) and C2–3 injections were performed in addition to the AO injections. In the third patient, an AA joint injection was concurrently done. In an abstract by Busch and Wilson, the authors presented two patients who obtained significant pain relief following combined repeat AO and AA joint injections.16 The first patient was a 41-year-old male who presented with right occiput, neck, and jaw pain stemming from a waterskiing accident. This patient underwent three successive right-sided AO and AA joint injections with local anesthetic and steroid, each of which provided several weeks of dramatic pain relief and increased range of motion in his neck. He eventually underwent an occiput to C2 fusion, which resulted in 100% pain relief. The second patient was a 70-year-old woman with a long history of pain in the left side of the neck, head, and eye. Over the course of 2 years, she received multiple, bilateral AO and AA joint blocks with local anesthetic and steroid, each of which resulted in excellent pain relief. The patient refused surgical stabilization, preferring to continue treatment with repeat injections. Potential complications of AO blocks include epidural and intrathecal injection, intravascular injection into the adjacent venous plexus, vertebral artery or carotid artery, and brief periods of ataxia.

ATLANTOAXIAL JOINT BLOCKS

Anatomy and function

The most distinctive feature of the second cervical vertebra, axis, is the dens or odontoid process. It is a vertical conical structure containing two articular facets, one oriented anteriorly to link up with the anterior arch of the atlas (i.e. the median atlantoaxial joint), the other situated posteriorly, corresponding to the transverse atlantal ligament extending between the two lateral masses of C1. The median AA joint functions as a pivot: the atlas pivots around the dens, carrying the head with it. On the lateral sides of the dens are two transverse processes, with laterally inclined upper articular surfaces that connect to the lateral masses of the atlas (i.e. the lateral atlantoaxial joints). Together, these structures form the three AA joints, one of the most intricate articulation complexes in the human body. The AA complex provides the widest range of motion among all joints in the cervical spine. In the sagittal plane, the dens allows for 5–10° of flexion and 10° of extension. In the horizontal plane, the AA joint permits 60–90° rotation.17,18 Hence, pain arising from the AA joints is often exacerbated by turning of the head. The innervation of the AA joint is from the ventral ramus of C2.

Presentation

Pain caused by AA arthropathy, like that for AO-mediated pain, is variable and inconsistent. Frequently, the AA joints are implicated in occipital pain radiating in the distribution of the greater occipital nerve (GON) because of the close proximity of the posterior branches of the C2 and C3 nerve roots, which join together to form the GON.19,20 Other articles have described AA joint pain as referred pain involving the medial branches of the C1–3 dorsal rami (the greater occipital and third occipital nerves for C2 and C3, respectively), and their convergence with trigeminal afferents in the trigeminocervical nucleus.18 This latter theory would explain studies implicating the AA joint in pain extending to the face.16 Consistent with the IHS criteria for cervicogenic headaches,6 in most studies on AA joint headache patients the pain tends to be unilateral.21

In the study by Dreyfuss et al. in which five asymptomatic volunteers were subjected to provocative injections of their AO and AA joints, evoked pain patterns for AA injections were much more uniform than for C0–1 blocks.8 The pain area in these five subjects was located primarily lateral and slightly posterior to C1–2. In the cervical Z-joint pain referral study by Fukui et al., the pain was referred to the occipital region in 3 of the 10 patients with chronic neck and occipital pain who underwent provocative lateral AA joint injections, and to the upper posterolateral cervical region in 100% of these subjects.14 These findings are consistent with those of the Dreyfuss study in asymptomatic individuals.8

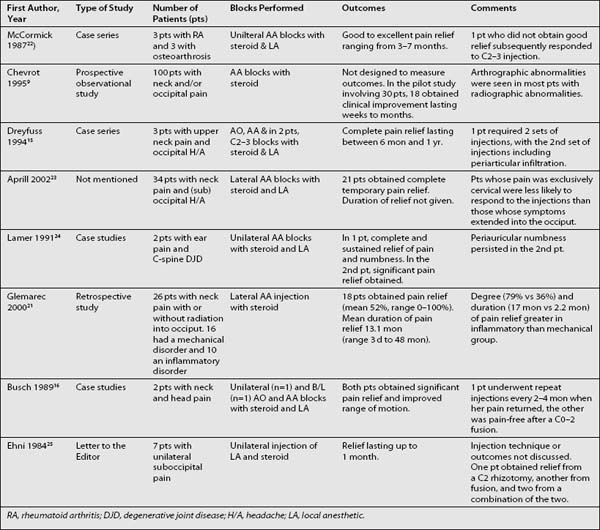

Outcome studies

Even though there are many reports in the literature regarding the therapeutic benefit of AA joint blocks with steroid and local anesthetic for chronic neck and occipital pain, the conclusions that can be drawn regarding this procedure are limited by the absence of any randomized clinical trials. In a retrospective study by Glemarec et al., the authors injected a lateral AA joint in 32 patients with chronic neck pain, with or without radiation in the GON distribution.21 Twenty-six patients, receiving 36 joint injections, were available for follow-up. Eighteen of these patients reported relief following the injection, with the mean pain score improvement being 52.3% (range 0% to 100%). The average duration of pain relief was 13.1 months (range 3 days to 48 months). In this study, the authors found that both the degree and duration of pain relief were greater in patients with inflammatory disorders than in those with mechanical causes of cervicalgia. In a case series by McCormick, the author treated two patients with rheumatoid arthritis and four with osteoarthrosis with C1–2 injections using lidocaine and steroid.22 Five of the six patients obtained immediate pain relief, attributable to the local anesthetic. In three patients, pain relief lasted 3–7 months. In one patient, excellent pain relief was obtained for 2 weeks, after which the patient underwent a posterior fusion. In the patient who did not obtain pain relief, subsequent injection of the C2–3 facet joint resulted in excellent analgesia. The results of studies assessing AO and AA joint blocks as a treatment for neck pain are summarized in Table 64.2.

CERVICAL ZYGAPOPHYSEAL JOINT INJECTIONS

Anatomy and function

The medial branches of the cervical posterior rami differ from those in the lumbar spine in that their main function is to supply the cervical Z-joints, with only small, discrete branches innervating the posterior neck muscles. It therefore seems logical that using cervical medial branch blocks (MBB) as a diagnostic tool for cervical facet arthropathy would carry a lower false-positive rate than lumbar MBB, although this has not been studied. The density of mechanoreceptors in cervical facet joints is higher than that in the lumbar region.26 In one study, the most common levels for symptomatic cervical facet joints were C2–3 and C5–6.27

Mechanism of injury

The most common cause of neck pain is whiplash injury. One of the earliest studies on this phenomenon was conducted by Severy et al., who subjected human volunteers to two rear-impact collisions at 13 kph and 15 kph, respectively.28 This seminal experiment demonstrated the importance of phasing differences between the vehicle and various body parts of the passenger during acceleration and deceleration as a source of injury. The peak acceleration of the vehicle preceded that of the torso, which in turn preceded that of the neck and head. This established that a critical element of whiplash involved inertial loading of the neck, as the torso abruptly moved forward under an initially stationary head.

In the early 1970s, Clemens and Burow performed a cadaveric study whereby 21 human corpses underwent 25 kph rear-end motor vehicle collisions with and without head rests.29 After the collisions, anatomical dissection was used to determine the site and extent of injuries. In the cadavers that underwent rear-end impacts without head rests, injuries to the cervical intervertebral discs were noted in 90% of cases, tears of the anterior longitudinal ligament in 80%, tears of the cervical Z-joint capsules were found in 40% of cadavers, and fractures of the vertebral bodies in 30%. In the cadavers protected by head rests, no injuries were found.

Modern studies on the biomechanics of whiplash injury have focused on high-speed photography and cineradiography. In an eloquent review by Bogduk and Yoganandan, the authors conclude that instead of the articular processes of the cervical Z-joints gliding across one another, the inferior articular processes of the moving vertebrae chisel into the superior articular processes of their supporting vertebrae during whiplash-type injuries.30 The posterior compression within the facet joints occurs about 100 msec after impact. Although this hypothesis is supported by volunteer and cadaver studies, several questions remain unanswered. The main question remains: why some whiplash victims suffer no pain or pain that quickly disappears, whereas others proceed down the path of years and years of suffering. Other causes of cervical facet pain include sports injuries, work-related accidents, and wearing head gear.

Presentation and prevalence

The main challenge in treating patients with cervical facet arthropathy in general, and whiplash in particular, is that no correlation has ever been established between symptoms and radiologic imaging. Consequently, the clinician must rely on other means to obtain a diagnosis. For lumbar facet arthropathy, recent studies have shown that there are no historical or physical examination findings that allow one to definitively identify the Z-joints as pain generators.31,32 This issue has not been adequately investigated in cervical pain, but at least one study has shown that a thorough physical examination can accurately diagnose the presence or absence of cervical Z-joint pain, and the level of involvement, as determined by diagnostic blocks.33 Signs of possible facet-mediated pain include limited range of motion, tenderness to palpation, and pain during intervertebral movement.

Clinical studies have been conducted in both normal volunteers and patients with suspected cervical facet pain to determine pain referral pattern from the joints.14,34,35 The results of these experiments are strikingly consistent. From C2–3, the pain pattern generally extends rostrally to the upper cervical region and suboccipital area. Infrequently, symptoms will extend towards the ear or further up the scalp. From C3–4, pain is referred to the upper and middle posterior neck, with occasional radiation into the lower occiput. From C4–5, the most common referral pattern is into the lower posterior cervical region, although in a significant percentage of people it extends into the middle posterior neck and suprascapular region. Pain from C5–6 is typically distributed to either the suprascapular region or lower neck, but can sometimes extend to the shoulder joint or midposterior neck. From C6–7, pain is usually referred into the upper scapula or lower neck. Pain from the C7–T1 Z-joint most frequently extends further down into the midscapula area.

There have been several studies done to determine the prevalence of cervical facet joint pain. In a retrospective study involving 318 patients with intractable neck pain who underwent cervical Z-joint blocks, provocative discography, or both, Aprill and Bogduk made a definite diagnosis of cervical facet pain in 25% of patients, while noting that another 38% of patients may have suffered from cervical Z-joint pain but were not appropriately investigated.36 Overall, 64% of the 128 patients who underwent single, intra-articular facet injections obtained significant pain relief.

Bogduk’s group from Newcastle, Australia, conducted two double-blind, controlled trials in the mid-1990s assessing the prevalence of cervical Z-joint pain in whiplash patients.27,37 In the first study, painful facet joints as determined by definite or complete pain relief using confirmatory MBB with lidocaine and bupivacaine were found in 54% of the 50 study subjects.27 In a later study, Lord et al. used three blocks to make a diagnosis of cervical Z-joint pain in the 68 study patients – confirmatory double blocks with lidocaine and bupivacaine, coupled with a negative response to placebo injections.37 In this paper, the overall prevalence of cervical facet pain was found to be 60%.

Outcomes for intra-articular injections

As is the case for lumbar Z-joint blocks, the International Spinal Injection Society (ISIS) advocates controlled diagnostic blocks as the only definitive means of diagnosing cervical facet joint pain.38 For diagnostic purposes, medial branch blocks have been shown to be as accurate as intra-articular injections provided contrast is used to prevent venous uptake. Due to the high incidence of false-positive blocks,39,40 ISIS recommends using either confirmatory blocks or placebo-controlled injections in order to increase the specificity.38

Although previous uncontrolled studies have reported prolonged pain relief from cervical facet blocks using steroid and local anesthetic,41,42 a double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Barnsley et al. failed to demonstrate a beneficial effect for intra-articular corticosteroids.43 In patients who respond to diagnostic intra-articular or medial branch blocks, radiofrequency denervation of these nerves has been shown in several uncontrolled44–48 and one placebo-controlled study49 to provide effective long-term pain relief. Radiofrequency procedures are discussed in detail in elsewhere within this book.

THIRD OCCIPITAL NERVE BLOCKS

One of the putative causes of headache and upper neck pain is osteoarthritis of or injury to the C2–3 zygapophyseal joint. Because pain from this facet joint is largely mediated through the third occipital nerve (TON), these headaches are often referred to as third occipital nerve headaches.50 In a prevalence study involving chronic neck pain in 100 patients following whiplash injury, Lord et al. found approximately 27% suffered from TON headache.51 The criteria for the diagnosis of TON headache in this study was complete eradication of head pain with two consecutive TON blocks done with lidocaine and bupivacaine, with the bupivacaine blocks providing longer pain relief than the lidocaine blocks. Of the 27 subjects diagnosed with TON headache, headache was the predominant complaint in 21 patients, and neck pain was the main complaint in 6.

The C2–3 facet joint is innervated by the third occipital nerve, the larger and more superficial of the two medial braches of the C3 dorsal ramus, and the C2 dorsal ramus. The C2–3 Z-joint may be particularly prone to injury in that it represents a transition zone between the atlantoaxial joint which accommodates rotation of the head, and the lower cervical spine which promotes flexion and extension of the neck. The history and physical examination are relatively non-specific in the diagnosis of third occipital neuralgia. Patients typically present with occipital headaches and neck pain, often after whiplash injury. Tenderness overlying the C2–3 facet joint may be the only sign suggesting this disorder.51

Third occipital nerve blocks have been advocated as the most reliable screening tool for headaches mediated by the TON.50,51 Nerve blocks performed with local anesthetics and steroids may provide prolonged pain relief in some patients, though this is unreliable. Radiofrequency denervation of the third occipital nerve is the best treatment option for patients who experience short-term pain relief with diagnostic injections. However, the one study that specifically addressed TON radiofrequency neurotomy in C2–3 Z-joint pain found a high failure rate.48 Ataxia is the main side effect of this procedure.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite its prevalence and the high toll it exacts on society, neck pain remains poorly understood, inadequately diagnosed, and extremely difficult to treat. In an attempt to alleviate the suffering of patients with neck pain, many clinicians turn to nerve blocks. Ideally, these blocks should be performed in the context of a multidisciplinary approach to therapy, which includes functional restoration, pharmacological treatment and, when indicated, alternative approaches to pain management. What is most surprising is how little research has been completed to understand the mechanisms underlying disorders causing neck pain. It is also striking that there is little evidence to support the use of many nerve blocks that are routinely done to treat neck pain. Presently, the primary use of nerve blocks in axial neck pain is for diagnostic purposes. Except for one placebo-controlled trial published in 1996 showing efficacy for radiofrequency denervation in the treatment of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain, the evidence supporting the other treatments outlined in this chapter is anecdotal. It is imperative that further research be done, both preclinically to help elucidate the mechanisms behind the various causes of neck pain, and clinically to justify specific treatments.

1 Guez M, Hildingsson C, Stegmayr B, et al. Chronic neck pain of traumatic and non-traumatic origin: a population-based study. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:576-579.

2 Guez M, Hildingsson C, Nilsson M, et al. The prevalence of neck pain: a population-based study from northern Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:455-459.

3 Merksey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definition of pain terms, 2nd edn., Seattle: IASP Press; 1994:103-111.

4 Haldeman S, Dagenais S. Cervicogenic headaches: a critical review. Spine J. 2001;1:31-46.

5 Sjaastad O, Fredriksen TA, Pfaffenrath V. Cervicogenic headache: diagnostic criteria. Headache. 1990;30:725-726.

6 Sjaastad O, Fredriksen TA, Pfaffenrath V. Cervicogenic headache: diagnostic criteria. Headache. 1998;38:442-445.

7 Racz GB, Sanel H, Diede JH. Atlanto-occipital and atlantoaxial injections in the treatment of headache and neck pain. In: Waldman SD, Winnie AP, editors. Interventional pain management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996:219-222.

8 Dreyfuss P, Michaelsen M, Fletcher D. Atlanto-occipital and lateral atlanto-axial joint pain patterns. Spine. 1994;19:1125-1131.

9 Chevrot A, Cermakova E, Vallee C, et al. C1–2 arthrography. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24:425-429.

10 Santavirta S, Konttinen YT, Lindqvist C, et al. Occipital headache in rheumatoid cervical facet joint arthritis. Lancet. 1986;20:695.

11 Bogduk N, Corrigan B, Kelly P, et al. Cervical headache. Aust Med J. 1985;143:202-207.

12 Vernon H. Spinal manipulation and headaches of cervical origin. J Manual Med. 1991;6:73-79.

13 Bogduk N. The anatomy and pathophysiology of neck pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2003;14:455-472.

14 Fukui S, Ohseto K, Shiotani M, et al. Referred pain distribution of the cervical zygapophyseal joints and cervical dorsal rami. Pain. 1996;68:79-83.

15 Dreyfuss P, Rogers J, Dreyer S, et al. Atlanto-occipital joint pain: a report of three cases and description of an intraarticular joint block technique. Reg Anesth. 1994;19:344-351.

16 Busch E, Wilson PR. Atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial injections in the treatment of headache and neck pain. Reg Anesth. 1989;14(Suppl 2):45.

17 Jofe M, White A, Panjabi M. Clinically relevant kinematics of the cervical spine. In: Sherk H, Dunn E, Eismont F, et al, editors. The cervical spine. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1989:57-69.

18 Bogduk N. The clinical anatomy of the cervical dorsal rami. Spine. 1982;7:319-330.

19 Bogduk N. The anatomy of occipital neuralgia. Clin Exp Neurol. 1981;170:167-184.

20 Lazorthes G. Les branches posterieures des nerfs rachidiens et le plan articulaire vertebral posterieur. Ann Med Phys. 1972;25:193-202. (in French)

21 Glemarec J, Guillot P, Laborie Y, et al. Intraarticular glucocorticoid injection in the lateral atlantoaxial joint under fluoroscopic control. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;67:54-61.

22 Mccormick CC. Arthrography of the atlanto-axial (C1–C2 joints): techniques and results. J Intervent Radiol. 1987;2:9-13.

23 Aprill C, Axinn MJ, Bogduk N. Occipital headaches stemming from the lateral atlanto-axial (C1–2) joint. Cephalagia. 2002;22:15-22.

24 Lamer TJ. Ear pain due to cervical spine arthritis: treatment with cervical facet injection. Headache. 1991;31:682-683.

25 Ehni G, Benner B. Occipital neuralgia and C1–2 arthrosis. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:127.

26 Bogduk N, Twomey L. Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine, 2nd edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1991.

27 Barnsley L, Lord SM, Wallis BJ, et al. The prevalence of chronic cervical zygapophyseal joint pain after whiplash. Spine. 1995;20:20-26.

28 Severy DM, Mathewson JH, Bechtol CO. Controlled automobile rear-end collisions, an investigation of related engineering and medical phenomena. Can Serv Med J. 1955;11:727-759.

29 Clemens JH, Burrow K. Experimental investigation on injury mechanisms of cervical spine at frontal and rear-frontal vehicle impacts. In: Proceedings of the 16th Stapp Car Crash Conference, Detroit, MI, 1972: 76–104.

30 Bogduk N, Yoganandan Y. Biomechanics of the cervical spine Part 3: minor injuries. Clin Biomech. 2001;16:267-275.

31 Jackson RP, Jacobs RR, Montesano PX. Facet joint injections in low back pain: a prospective statistical study. Spine. 1988;13:966-971.

32 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, et al. Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the lumbar zygapophyseal joints. Is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity? Spine. 1994;19:1132-1137.

33 Jull G, Bogduk N, Marsland A. The accuracy of manual diagnosis for cervical zygapophyseal joint pain syndromes. Med J Aust. 1988;148:233-236.

34 Dwyer A, Aprill C, Bogduk N. Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns I: a study in normal volunteers. Spine. 1990;15:453-457.

35 Aprill C, Dwyer A, Bogduk N. Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns II: a clinical evaluation. Spine. 1990;15:458-461.

36 Aprill C, Bogduk N. The prevalence of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain. A first approximation. Spine. 1992;17:744-747.

37 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, et al. Chronic zygapophyseal joint pain after whiplash: a placebo-controlled prevalence study. Spine. 1996;21:1737-1744.

38 Bogduk N. International Spinal Injection Society guidelines for the performance of spinal injection procedures. Part I: zygapophyseal joint blocks. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:285-302.

39 Barnsley L, Lord SM, Wallis BJ, et al. False-positive rates of cervical zygapophyseal joint blocks. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:124-130.

40 Barnsley L, Lord S, Bogduk N. Comparative local anesthetic blocks in the diagnosis of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain. Pain. 1993;55:99-106.

41 Roy DF, Fleury J, Fontaine SB, et al. Clinical evaluation of cervical facet joint infiltration. J Can Assoc Radiol. 1988;39:118-120.

42 Slipman CW, Lipetz JS, Plastaras CT, et al. Therapeutic zygapophyseal joint injections for headaches emanating from the C2–3 joint. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80:182-188.

43 Barnsley L, Lord SM, Wallis BJ, et al. Lack of effect of intraarticular corticosteroids for chronic pain in the cervical zygapophyseal joints. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1047-1050.

44 Schaerer JP. Radiofrequency facet denervation in the treatment of persistent headache associated with chronic neck pain. J Neurol Orthop Surg. 1980;1:127-130.

45 Sluijter ME, Koetsveld-Baart CC. Interruption of pain pathways in the treatment of the cervical syndrome. Anaesthesia. 1980;35:302-307.

46 van Suijekom HA, van Kleef M, Barendse GA, et al. Radiofrequency cervical zygapophyseal joint neurotomy for cervicogenic headache: a prospective study of 15 patients. Funct Neurol. 1998;13:297-303.

47 Sapir DA, Gorup JM. Radiofrequency medial branch neurotomy in litigant and nonlitigant patients with cervical whiplash. A prospective study. Spine. 2001;26:E268-E273.

48 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Bogduk N. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy in the treatment of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain: a caution. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:732-739.

49 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, et al. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721-1726.

50 Bogduk N, Marsland A. On the concept of third occipital headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:775-780.

51 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, et al. Third occipital nerve headache: a prevalence study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1187-1190.