Therapeutic drug monitoring

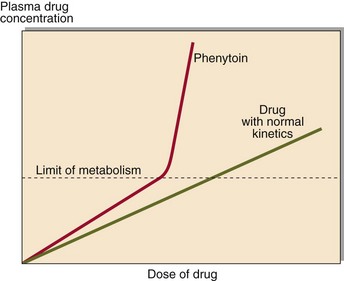

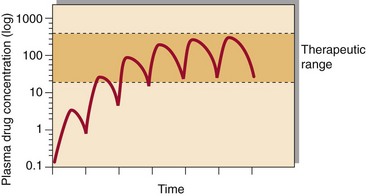

Following the administration of a drug, the graph of plasma concentration against time, plotted on semi-logarithmic graph paper, will look like that in Figure 59.1. Analysis of such graphs can allow an estimate of the half-life of the drug ( ) and the volume of distribution, which is higher if the drug is taken up by tissues. These can be used to estimate the correct dose to give. After several similar doses have been given, the pattern reaches a steady state at which the plasma drug concentration will oscillate between a peak and a trough level. It usually takes about five half-lives for the steady state to be attained. In the steady state there is a stable relationship between the dose and the effect, and decisions can be made with confidence. For most drugs there is a linear relationship between dose and plasma concentration. However, phenytoin shows non-linear kinetics (Fig 59.2).

) and the volume of distribution, which is higher if the drug is taken up by tissues. These can be used to estimate the correct dose to give. After several similar doses have been given, the pattern reaches a steady state at which the plasma drug concentration will oscillate between a peak and a trough level. It usually takes about five half-lives for the steady state to be attained. In the steady state there is a stable relationship between the dose and the effect, and decisions can be made with confidence. For most drugs there is a linear relationship between dose and plasma concentration. However, phenytoin shows non-linear kinetics (Fig 59.2).

Fig 59.1 Plasma drug concentration shown after a series of identical doses equally spaced. After approximately 5 half-lives steady state is achieved.

Interpretation of drug levels

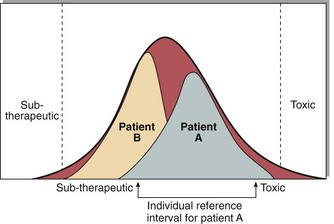

A great deal of information is required in order to interpret drug concentrations correctly. Where concentrations are lower than expected, the most likely cause is non-compliance. Higher than expected concentrations, in the absence of an increase in dose, indicate that a change has taken place either in other drug therapy or in hepatic or renal function. It is much easier to interpret results if cumulative reports, including dosing details, are available, since these allow comparisons between drug levels achieved. The population reference interval for each drug indicates roughly the limits within which most patients will show maximum therapeutic effect with minimum toxicity. However, a level that is therapeutic in one patient may give rise to toxicity in another (Fig 59.3). The most likely reasons for the plasma drug concentration to fall above or below the reference interval are given in Table 59.1.

Table 59.1

Common reasons for sub-therapeutic or toxic levels

Sub-therapeutic levels

Non-compliance

Dose too low

Malabsorption

Rapid metabolism

Toxic levels

Overdose

Dose too high

Dose too frequent

Impaired renal function

Reduced hepatic metabolism

Although many drugs are measured in specialist units, such as cardiology, neurology and oncology, only a few drugs are required to be measured in most laboratories. Examples of drugs for which TDM is appropriate, and the reasons why, are shown in Table 59.2. Many of these drugs have a low therapeutic index. This means that the concentration at which toxicity occurs is not much higher than that which is required for therapeutic effect. It should be noted that some drugs are highly bound to albumin. In patients with low albumin concentrations, the total drug concentration may be low but the effective (free) level may be adequate.

Table 59.2

Drugs for which therapeutic drug monitoring is appropriate

| Drug(s) | Reason for monitoring |

| Anticonvulsants | |

| Phenytoin | Non-linear kinetics |

| Carbamazepine | |

| Antiarrhythmics | |

| Digoxin | Very low therapeutic index |

| Sensitive to renal dysfunction | |

| Amiodarone | Wide variability in half-life especially in neonates |

| Aminoglycosides | Nephrotoxic and ototoxic |

| Antitubercular drugs | Drug interactions |

| Isoniazid | Slow and fast metabolizers exist |

| Immunosuppressants | |

| Ciclosporin A | Nephrotoxic. Measure at 2 hours |

| Tacrolimus | Nephrotoxic. Measure trough levels |

| Lithium | Very low therapeutic index |

| Methotrexate | If slowly metabolized folate therapy required |

| Theophylline | Low therapeutic index |

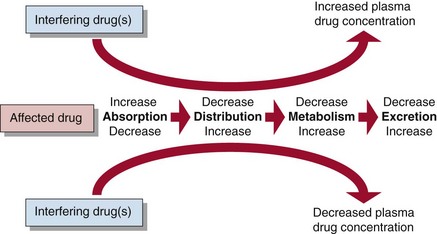

Drug interactions

Some drugs interfere with the metabolism and excretion of others, and as a result the addition of one drug will alter the plasma concentration of another (Fig 59.4). In such circumstances, rather than attempt to establish a new steady state, it may be appropriate, when a patient is receiving a short course of a drug such as an antibiotic, temporarily to change the dose of the drug it affects. Drug interactions are particularly problematical where several drugs must be co-prescribed, as in treatment of tuberculosis, AIDS and cancer.