4 THE WRIST AND HAND

Applied Anatomy

THE HAND (Fam, 2003)

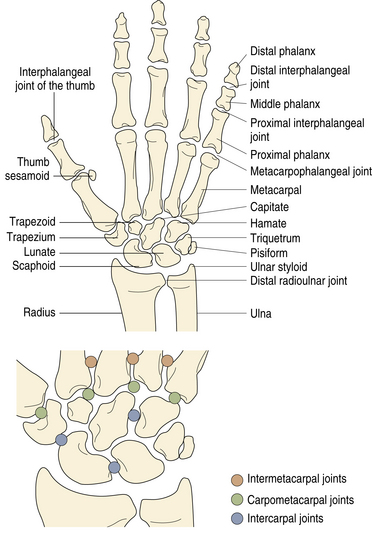

The hand is the chief sensory organ of touch and is uniquely adapted for grasping. The radial side of the hand performs a pinch grip between the fingers and thumb, and the ulnar side performs a power grip between the fingers and palm. The bones of the hand can be divided into a central, fixed unit for stability and three mobile units for dexterity and power. The fixed unit consists of the eight carpal bones tightly bound to the second and third metacarpals (Figure 4-1). The three mobile units projecting from the fixed unit are:

WRIST JOINT

The radiocarpal joint is the proximal articulation of the wrist and is an ellipsoid joint between the distal radius and articular disk proximally and the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum distally (see Figure 4-1). The capsule is strengthened by the radiocarpal (dorsal and volar) ligaments. The articular disk, or triangular fibrocartilage of the wrist, joins the radius to the ulna. Its base is attached to the ulnar border of the distal radius, and its apex is attached to the root of the ulnar styloid process. The synovial cavity of the distal radioulnar joint is L-shaped and extends distally beneath the triangular fibrocartilage but is usually separated from the radiocarpal joint.

The radiocarpal, midcarpal distal radioulnar, and CMC joints do not communicate under normal circumstances. The presence of any communication, tested by wrist arthrography or MR arthrograms, implies torn ligaments or a torn capsule between them. The midcarpal joint is in continuity with the intercarpal joints except for the pisotriquetral articulation, which communicates with the radiocarpal joint (see Figure 4-1).

The carpal bones form a volar concave arch or carpal tunnel, with the pisiform and hook of the hamate on the ulnar side and the scaphoid tubercle and the crest of the trapezium on the radial side. The four bony prominences are joined by the flexor retinaculum (transverse carpal ligament), which forms the roof of the carpal tunnel. The distal flexion crease of the wrist marks the proximal border of the retinaculum. The palmaris longus (absent in 10% to 15% of the population) partly inserts into the flexor retinaculum and partly fans out into the palm, forming the palmar aponeurosis (fascia). The aponeurosis broadens distally and divides into four digital slips that attach to the finger flexor tendon sheath, MCP joint capsules, and proximal phalanges. There is usually no digital slip to the thumb (Markison, 1987).

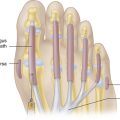

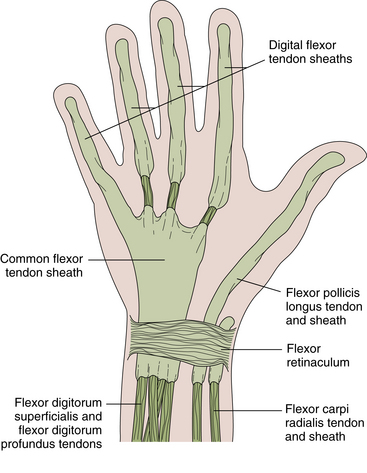

The common flexor tendon sheath encloses the long flexor tendons of the fingers (Strauch, 1985) (flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus) and extends from approximately 2.5 cm proximal to the wrist crease to the mid palm. It runs with the flexor pollicis longus tendon sheath and the median nerve through the carpal tunnel (Figure 4-2). The tendon sheath of the little finger is usually continuous with the common flexor sheath. The flexor pollicis longus tendon to the thumb runs through a separate tenosynovial sheath but may join the common flexor sheath. The flexor carpi radialis is invested in its own short tendon sheath as it crosses the volar aspect of the wrist between the split radial attachment of the flexor retinaculum. It is separated from the carpal tunnel by the deep portion of the transverse carpal ligament. The flexor retinaculum straps down the flexor tendons as they cross at the wrist. The ulnar nerve, artery, and vein cross over the retinaculum but are covered by a fibrous band, the superficial part of the transverse carpal ligament, to form the ulnar tunnel, or Guyon canal.

FIGURE 4-2 FLEXOR TENDONS AND TENDON SHEATHS OF THE WRIST AND FINGERS.

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds.: Rheumatology, 3rd ed. London: Mosby, 2003.)

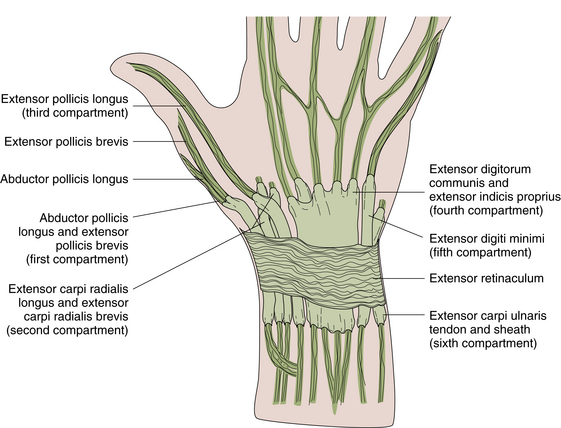

On the dorsum of the wrist, the extensor tendons pass through six tenosynovial, fibro-osseous tunnels beneath the extensor retinaculum: 1) the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis (usually in a single sheath), which constitute the first, most radial extensor compartment; 2) the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis; 3) the extensor pollicis longus; 4) the extensor digitorum communis and extensor indicis proprius; 5) the extensor digiti minimi; and 6) the extensor carpi ulnaris, the most ulnar extensor compartment (Figure 4-3). Each tenosynovial sheath extends about 2.5 cm proximally and distally from the retinaculum. The extensor retinaculum, by its deep attachments to the distal radius and ulna, binds down and prevents bowstringing of the extensor tendons as they cross the wrist. The anatomic snuffbox corresponds to the depression between the extensor pollicis longus tendon and the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis.

CARPOMETACARPAL JOINTS

The first CMC joint is a saddle-shaped, very mobile articulation between the trapezium and the base of the first metacarpal. It allows 40° to 50° of thumb flexion–extension parallel to the plane of the palm and 40° to 70° of adduction–abduction perpendicular to the plane of the palm. These movements are important in bringing the thumb in opposition with the fingers. The second and third CMC joints are relatively fixed, but the fourth and fifth are mobile, allowing the fourth and fifth metacarpals to flex forward (15° to 30°) toward the thumb during power grip.

METACARPOPHALANGEAL JOINTS

The metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints are ellipsoid joints that lie about 1 cm distal to the knuckles (metacarpal heads; see Figure 4-1). Their capsule is strengthened by the radial and ulnar collateral ligaments on the sides and by the volar plate on the volar surface. Because of the cam shape of the metacarpal head, the collateral ligaments are loose in the neutral position, allowing radial and ulnar deviations, but become tight in the flexed position, preventing side-to-side motion, referred to as a sagittal cam effect. The deep transverse metacarpal ligament joins the volar plates of the second to fifth MCP joints. The MCP joint of the thumb is large and has two sesamoid bones overlying its volar surface.

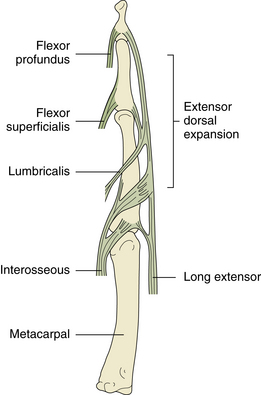

When the long extensor tendon of the digit reaches the metacarpal head, it is joined by the tendons of the interossei and lumbricals and expands over the dorsum of the MCP joint and digit to form the extensor hood or extensor expansion (Figure 4-4). The expansion divides over the dorsum of the proximal phalanx into an intermediate slip, inserted principally into the base of the middle phalanx, and two collateral slips inserted into the base of the distal phalanx (von Schroeder, 1997).

FIGURE 4-4 TENDON INSERTIONS OF THE FINGER AND EXTENSOR DORSAL EXPANSION (HOOD).

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds.: Rheumatology, 3rd ed. London: Mosby, 2003.)

The first MCP joint permits 50° to 70° flexion and 10° to 30° extension. Radial and ulnar deviations are limited to less than 10° to 20°. The other MCP joints allow 100° flexion, 10 to 20° extension, and 35° of radial and ulnar movement. The extensor pollicis brevis, extensor indicis proprius, extensor digitorum communis, and extensor digiti minimi extend the MCP joints (von Schroeder, 1993). The flexors are the flexor pollicis brevis, lumbricals, interossei, and flexor digiti minimi brevis, assisted by the long flexors. Radial and ulnar movements at the second to fifth MCP joints are a function of the intrinsic muscles.

INTERPHALANGEAL JOINTS

The flexor tendon sheaths for the fingers enclose the tendons of the flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus to their insertions on the middle and distal phalanges, respectively. The sheaths extend from just proximal to the MCP joints to the bases of the distal phalanges (see Figure 4-2). The flexor sheath of the little finger is often continuous with the wrist common flexor tendon sheath. The thumb flexor pollicis longus tendon sheath extends proximally to the carpal tunnel. Segmental condensations, or annular pulleys, in the digital flexor sheaths prevent bowstringing of the tendons and are biomechanically critical for full digital flexion.

Differential Diagnosis of Wrist and Hand Pain

Pain in the wrist and hand may have its origin in the bones and joints of the wrist and hand, palmar fascia, tendon sheaths, nerve roots, peripheral nerves, or vascular structures, or it may be referred from the cervical spine, thoracic outlet, shoulder, or elbow (Table 4-1). Important points in the history include onset, location, character, duration, and modulating factors of pain. A history of unaccustomed, repetitive, or excessive hand activity is particularly important in the diagnosis of wrist, thumb, or finger tenosynovitis caused by an overuse syndrome. A detailed occupational history is essential for determining whether the hand tendinitis is work related, either as a cumulative trauma disorder or as an acute injury. Abnormal tensile stresses that exceed the elastic limits of tendons can lead to cumulative microfailure of the molecular links between tendon fibrils, a phenomenon referred to as fibrillar creep. With aging, tendons become less flexible and less elastic, rendering them more susceptible to injury. A shortened musculotendinous unit, from lack of regular stretching exercises, is more prone to cumulative trauma disorder (Strauch, 1985).

| Articular | Arthritis of wrist, MCP, PIP, and/or DIP joints |

| Joint neoplasms | |

| Periarticular | |

| Subcutaneous | RA nodules, gouty tophi, glomus tumor |

| Palmar fascia | Dupuytren contracture |

| Tendon sheath | de Quervain tenosynovitis |

| Wrist volar flexor tenosynovitis (including carpal tunnel syndrome) | |

| Thumb or finger flexor tenosynovitis (trigger thumb or finger) | |

| Pigmented villonodular tenosynovitis | |

| Acute calcific periarthritis | Wrist, MCP, and rarely PIP and DIP |

| Ganglion | |

| Osseous | |

| Fractures, neoplasms, infection | |

| Osteonecrosis including Kienböck disease (lunate) and Preiser disease (scaphoid) | |

| Neurologic | |

| Nerve entrapment syndromes | |

| Median nerve | Carpal tunnel syndrome (at wrist) |

| Pronator teres syndrome (at pronator teres) | |

| Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome | |

| Ulnar nerve | Cubital tunnel syndrome (at elbow) |

| Guyon canal (at wrist) | |

| Radial nerve | Radial nerve palsy, radial tunnel syndrome, Wartenberg syndrome |

| Lower brachial plexus | Thoracic outlet syndrome, Pancoast tumor |

| Cervical nerve roots | Herniated cervical disk, tumors |

| Spinal cord lesion | Spinal tumors, syringomyelia |

| Vascular | |

| Vasospastic disorders (Raynaud disease) | Scleroderma, occupational vibration syndrome |

| Vasculitis with digital ischemic ulcers | SLE, RA |

| Referred Pain | |

| Cervical spine disorders | |

| Chronic regional pain syndrome | Shoulder–hand syndrome, causalgia, reflex sympathetic dystrophy |

| Cardiac | |

| Angina pectoris |

DIP, distal interphalangeal; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus

Physical Examination of the Hand and Wrist

INSPECTION

With the hands on the examining table, one makes a general assessment of age, inflammation, atrophy, deformity, and asymmetry. Age-related changes include prominent veins on the dorsum of the hand, mild atrophy of the intrinsic muscles, lentigines on the skin and osteoarthritic prominences at the CMC joint at the base of the thumb, and osteophytes at the DIP and PIP joints. Osteoarthritic changes are ubiquitous and eventually result in such enlargement of the small joints of the fingers and deformity (McMurtry, 1986).

Physical Examination of the Digits

ASSESSING SYNOVITIS OF THE JOINTS AND TENDONS

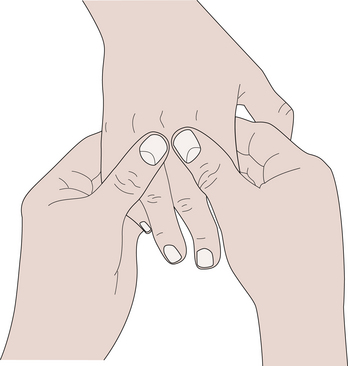

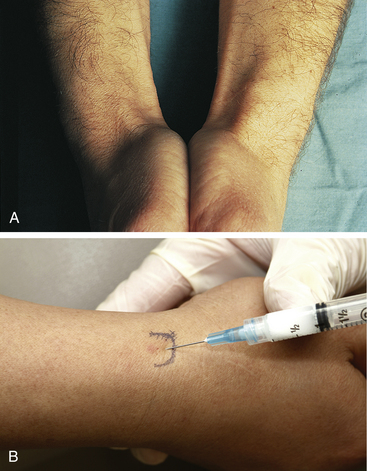

Chronic synovitis is best assessed on the dorsum of the hand and wrist, where the tendons and joints are close to the surface and have fewer constraining structures over them. Synovitis of the joints produces a diffuse swelling over the joint and is uniformly tense and sometimes warm to the touch (McMurtry, 1986). The PIP and DIP joints are palpated by compressing laterally and/or gently forcing the joint into hyperextension for tenderness (stress pain). Synovial thickening and effusion are assessed by the examiner using the thumbs and forefingers of both hands placed on opposite sides of the joint (Figure 4-5). An effusion can be detected by the balloon sign: compression of the joint by one hand produces ballooning, or a hydraulic lift, sensed by the other hand. Unlike PIP synovitis, dorsal knuckle pads produce a nontender thickening of the skin localized to the dorsal surface of the PIP joints. The thumb MCP joint can be assessed in the same way. Tenderness in the MCP joints of the second to fifth digits are assessed by placing the examiner’s thumb under the volar aspect of the proximal phalanx, the fingers on the dorsum of the hand, and stressing the joint into hyperextension. An effusion can be ballooned by compressing the flexed MCP joint from the dorsoradial side and palpating the fluctuance from the dorsoulnar side (Figure 4-6).

FIGURE 4-5 PALPATION OF THE PROXIMAL INTERPHALANGEAL JOINT.

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds.: Rheumatology, 3rd ed. London: Mosby, 2003.)

DEFORMITY PATTERNS

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

RA can result in deformity of any or all of the joints of the hand and wrist. Boutonnière’s deformity describes a finger with flexion of the PIP joint and hyperextension of the DIP joint (Figure 4-7A). A swan-neck deformity describes the appearance of a finger in which there is hyperextension of the PIP joint and flexion of the DIP joint (see Figure 4-7B). In swan-neck finger deformity, tightness and shortening of the intrinsic muscles (interossei and lumbricals) results in restriction of PIP flexion when the MCP joint is extended. Therefore, with the MCP joint extended, the range of PIP flexion is less than when the MCP joint is flexed (positive Bunnell test). Z-shaped deformity of the thumb is caused by flexion of the MCP joint and hyperextension of the IP joint (see Figure 4-7C). Z-shaped deformities, finger deformities, and MCP synovitis produce a diffuse swelling of the joint that may obscure the valleys between the knuckles. MCP joint deformities include ulnar drift, volar subluxation (often visible as a “step”), and flexion deformities. The extensor tendons subluxate into the valleys on the ulnar side of their respective digits.

Dupuytren Contracture

In Dupuytren contracture, the aponeurotic thickening of the palmar fascia may extend distally to involve the digits. The fingers become flexed at the MCP joints by taut fibrous bands, or “cords,” that radiate from the palmar fascia, and the hand cannot be placed flat on a table (positive tabletop test) (Saar, 2000).

Osteoarthritis (OA)

Osteophytes at the DIP and PIP joints (Heberden and Bouchard nodes respectively) occur with age or following trauma and may be associated with gradual ulnar drift of the fingers. “Squaring” of the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint at the base of the thumb due to OA is particularly common. The thumb eventually becomes more adducted toward the hand. At the wrist, OA can result in chronic swelling, bland effusions, and decreased active and passive range of motion.

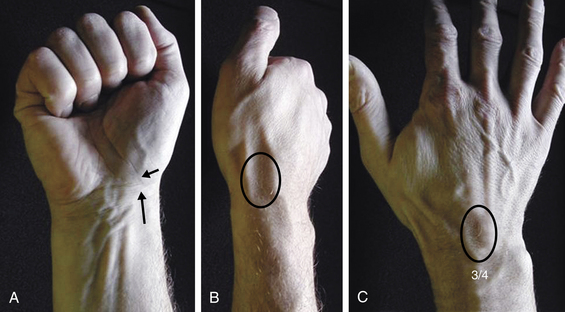

PALPATION OF THE WRIST: ASSESSING BONES, JOINTS, AND LIGAMENTS

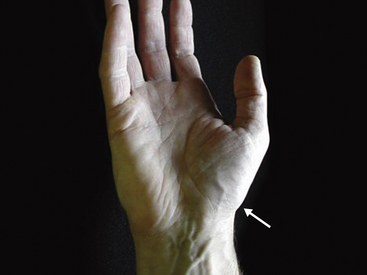

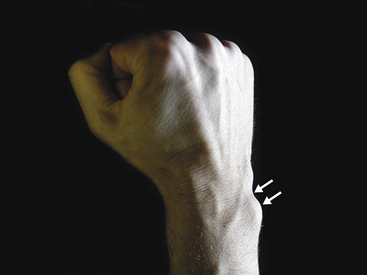

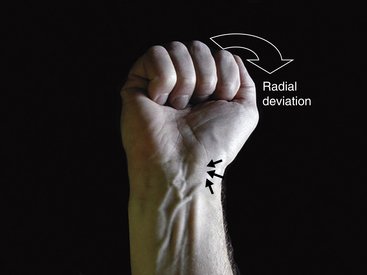

The wrist is best examined in the “arm wrestling” position, with the patient’s elbow on the examining table and the hand up (Figure 4-8). In this position, motion in all directions is checked, all of the carpal bones can be palpated, and key ligaments can be assessed. The scaphoid (Beckenbaugh, 1984) is palpated at three points (Figure 4-9). First, the scaphoid tubercle is prominent on the volar aspect of the wrist proximal to the thenar eminence (Figure 4-9A). It becomes more prominent as the scaphoid flexes in the volar direction while the wrist is brought into radial deviation. The Watson maneuver (scaphoid shift) (Watson, 1988) tests the integrity of the scapholunate ligament (see Scapholunate Ligament, p. 39; Figure 4-19). Tenderness directly at the scaphoid tubercle may be due to a fracture of the tubercle or osteoarthritis at the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid (STT) joint. The second point to palpate the scaphoid is the anatomical snuffbox on the radial aspect of the wrist (Figure 4-9B). With the examiner’s fingertip in the snuffbox, ulnar deviation of the wrist will allow palpation of the scaphoid ridge in the waist of the bone. Tenderness here represents acute fracture (De Smet, 2002), fracture nonunion (pseudoarthrosis), or synovitis. The third place to examine the scaphoid and scapholunate region is between the third and forth compartments on the dorsum of the wrist and about 2 cm distal to the Lister tubercle (Figure 4-9C). This “soft spot” is also used for injecting the radiocarpal joint and as an arthroscopic portal. Palpations at this spot during wrist flexion will bring the proximal portion of the scaphoid under the examiner’s finger.

The lunate is directly distal to the distal radioulnar joint, below the tendons of the fourth and fifth compartments (Figure 4-10). It is not readily distinguishable, but like the proximal scaphoid, the lunate is palpable as the wrist is brought into full flexion. Tenderness here is associated with Kienböck osteonecrosis of the lunate.

The dorsal prominence of the triquetrum is readily palpable distal to the ulnar head (Figure 4-11). It becomes more prominent in radial deviation. Tenderness may be associated with a shear fracture of the prominence resulting from a fall. A smaller prominence may be palpable on the ulnar side of the triquetrum. Volar to the triquetrum is the pisiform at the base of the hypothenar eminence (Figure 4-12); a sesamoid bone in the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon, it is slightly mobile in a radial-ulnar direction. Osteoarthritis may develop at the synovial joint between the pisiform and triquetrum and is characterized by pain on direct palpation of the joint at the ulnar side of the hand and by pushing the pisiform against the triquetrum while moving it side to side.

Approximately 2 cm distal and radial to the pisiform is the hook of the hamate (Figure 4-13). It is a vaguely defined prominence on palpation and may be slightly tender in normal individuals. It is significantly tender following a fracture or fracture nonunion of the hook. The dorsum of the hamate is palpable as a flat region just distal to the dorsal triquetral prominence (Figure 4-14). The fifth carpometacarpal (CMC) joint is assessed by palpating directly over the joint as the metacarpal is flexed and extended. Tenderness may represent post-traumatic or de novo osteoarthritis at the joint.

FIGURE 4-13 THE HOOK OF THE HAMATE.

A vague prominence just distal and radial from the pisiform (p).

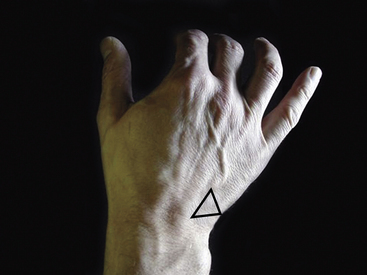

FIGURE 4-14 THE DORSUM OF THE HAMATE.

A flat region (triangle) just distal to the dorsal triquetral prominence.

The dorsum of the capitate is palpable at its waist (Figure 4-15). This is a soft spot at the base of the third metacarpal. It is located approximately 1 cm distal and ulnar to the dorsal soft spot, where the scaphoid was palpated just beyond the Lister tubercle.

The dorsal base of the index metacarpal flares, and this bony prominence can increase with age and osteoarthritis, in which case it is referred to as a carpal boss (Figure 4-16). The trapezoid bone is located proximal to the prominent base of the second metacarpal and under the extensor carpi radialis longus tendon that inserts into the metacarpal.

At the base of the thumb metacarpal, and with rotational movement of the metacarpal, the CMC joint and the trapezium are palpated (Figure 4-17). This is best assessed by pinching the joint region on either side of the tendons of the first compartment with the pulps of the examiner’s index finger and thumb. Osteoarthritis is particularly common at this joint, especially in women, and can be assessed by axially loading the metacarpal and translocating or “grinding” the CMC joint to look for pain and crepitus. “Squaring” of the joint is noted on inspection of patients with moderate to severe osteoarthritis.

The distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) is palpable as a sulcus on the radial side of the ulnar head on the dorsum of the wrist. It is a forearm joint through which pronation and supination occur. This arc of motion is tested with the elbow locked on the examination table, or with the elbow at the patient’s side, to prevent shoulder contribution to the motion. Tenderness at the joint is most commonly due to post-traumatic osteoarthritis due to fracture, incongruence associated with a distal radius fracture or malunion; de novo osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthritis, especially rheumatoid, occur here as well.

The sulcus between the ulnar head and the dorsal prominence of the triquetrum is the location of the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC; Figure 4-18). The central disk component supports the carpus, whereas the fibrous ligaments stabilize the DRUJ. Tenderness at the TFCC implies a degenerative or traumatic tear. Degenerative changes commonly occur with age and in individuals who have an ulnar length that exceeds the radial length, known as ulnar-positive variance. Acute tears can occur following a fall. Tenderness can also be tested on the volar aspect of the TFCC, just proximal to the pisiform and under the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) tendon. In this region, the volar ulnocarpal ligaments contribute to the TFCC structure. Finally, TFCC tenderness can be noted directly on the ulnar aspect of the wrist beyond the head of the ulna and between the FCU and extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) tendons. This region, sometimes referred to as the mini snuffbox, also contains the ulnar styloid, which can become tender following fracture or nonunion. Stability of the DRUJ, as determined primarily by the integrity of the TFCC, is best tested by stabilizing the distal radius and carpus with one hand, on the radial aspect of the wrist, and translating the neck of the ulna in the volar and dorsal direction with the other hand. Pain and relative motion between the ulnar head and the radius should be assessed and compared to the other side, because the joint normally subluxes a few millimeters. The joint should be completely stable with the wrist in full pronation and full supination. The test can also be performed by looking for the “piano key” volar or dorsal shift of the head of the ulna as the patient pushes the hand down on a table with an outstretched arm or pushes the hand up against resistance.

PROVOCATIVE CARPAL TESTING FOR INSTABILITY AND ARTHRITIS

Normal function of the wrist depends on pain-free motion and stability. Trauma and inflammatory conditions can disrupt the intrinsic ligaments of the wrist, resulting in instability and eventual degenerative changes (De Smet, 2002). Similarly, trauma and inflammation that directly affect the cartilage surfaces of the carpus can also result in degeneration. The proximal carpal row—consisting of the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum—function as a unit that allows radiocarpal articulation but also provides a concavity to support and allow motion of the distal carpal row. For the proximal row to work as a unit, the scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments must be intact.

Scapholunate Ligament

Flexion of the scaphoid with radial deviation of the hand is a normal motion of the proximal row that cannot be overcome by the examiner’s finger in the scaphoid tubercle (Beckenbaugh, 1984) (Figure 4-19). If it can be overcome, or if the scaphoid is ballotable, scapholunate ligament (SLL) laxity or tears are probable. The Watson test is performed by applying pressure on the flexed scaphoid tubercle while moving the hand back into ulnar deviation. Sudden and sharp dorsal wrist pain during this test indicates a significant SLL tear, resulting in instability and eventual osteoarthritis.

Midcarpal Instability

This instability is characterized by vague, fatigue-like aching pain or a painful clunk with certain positions and is tested by stabilizing the radius with one hand and volarly translocating the carpus by pushing down on the hamate or capitate on the dorsum of the wrist (Figure 4-20). The wrist is reduced by bringing it into ulnar deviation, resulting in the “catch-up clunk” (Lichtman, 1984). Subluxation of the wrist is present in virtually everyone, but tenderness, pain, or reproduction of symptoms is important in the diagnosis of this type of instability.

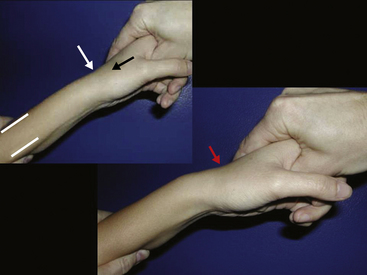

TENDONS AT THE WRIST

The first of six dorsal extensor compartments is at the radial styloid region of the wrist and contains the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons. Inflammation here, known as de Quervain tenosynovitis, is assessed with the Finkelstein test (Finkelstein, 1930 and Field, 1979), in which the thumb is held in the palm by the patient’s flexed fingers as the wrist is passively brought into ulnar deviation. The maneuver reproduces the pain over the distal radius and the radial side of the wrist.

Inflammation of the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and brevis (ECRB) can occur in individuals who perform repetitive extension of the wrist, such as rowers. Pain is located at the junction where the two tendons emerge from under the muscles of the first compartment, approximately 3 cm proximal to the Lister tubercle on the dorsum of the distal radius (Wood, 1973). Inflammation here is known as intersection syndrome. The ECRL, and less commonly the ECRB, can also become inflamed at their insertion sites at the bases of the second and third metacarpals, respectively.

Both of the two wrist flexors can become symptomatic with repetitive or excessive flexion. The flexor carpi radialis (FCR) typically becomes inflamed on the ulnar side of the scaphoid tubercle, where it travels down and into a tunnel at the trapezial ridge. The flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) typically becomes inflamed proximal to the pisiform.

NERVES AT THE WRIST

The three major nerves at the wrist are assessed by percussion and compression and by assessing the appearance and power of the muscles that they innervate. The median nerve is percussed proximal to the flexor retinaculum, just radial to the palmaris longus tendon at the distal wrist crease. With symptomatic compression of the nerve in carpal tunnel syndrome, percussion produces paresthesia in the distribution of the nerve (Tinel sign) in the thumb, index, and middle fingers and the radial half of the ring finger. Sustained flexion of the wrist for 60 seconds can also induce finger paresthesias (Phalen wrist flexion sign). If the wrist cannot be flexed because of arthritis, pressure over the median nerve for 60 seconds often produces the same effect. The median nerve function is also assessed by gauging muscle atrophy and power of the thenar eminence (Palumbo, 2002).

Injections of the Hand and Wrist

INTRODUCTION

With the hand and wrist, after an articular injection is complete, the patient should be advised to keep the area clean and dry for 24 hours to avoid infection. Pain after injection occurs most often with tissue infiltration, such as for de Quervain syndrome. Along with analgesic tablets, ice in a plastic bag, applied on and off every 30 seconds, can provide relief. Where local anesthetic is infiltrated near a nerve (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome), patients should be apprised of the possibility of paresthesia for a couple of hours afterward (Fam, 1995).

Interphalangeal Joints

These joints are injected using a 25 gauge, 5/8 inch needle and a 1 mL syringe. Draw up 0.1 mL of local steroid and 0.1 mL of local anesthetic. The volume of injection should not exceed 0.3 mL to avoid stretching and damage of the capsule. Cadaveric studies have indicated that without ultrasound guidance, the needle is intraarticular in only 56% of cases; so if aspiration is important for diagnosis, ultrasound should be used (Raza et al, 2003). With the patient recumbent, the hand is placed palm down, fingers extended, on the examining table. For steroid injection the needle should be placed into the dorsomedial or dorsolateral aspect of the joint until the tip touches the articular cartilage. A slow injection is associated with slight ballooning of the capsule (Figure 4-21).

Metacarpophalangeal Joints

MCP joints are injected using a 25 gauge, 5/8 inch needle and 1 mL syringe. Draw up 0.2 mL of local steroid and 0.1 mL of local anesthetic. The volume of the injection should not exceed 0.4 mL to avoid stretching and damage of the capsule. The needle should be placed into the dorsomedial or dorsolateral aspect of the extended joint. As with the interphalangeal joint, it is often difficult to enter the intraarticular joint space. As the joint is injected, inflation of the capsule is palpable (Figure 4-22).

Wrist Joint

The radiocarpal joint is best approached from the dorsum of the wrist. The patient is supine with the hand prone on the examining table. A 22 gauge, 1 or 1½ inch needle is used. Local anesthetic can be infiltrated as the needle is inserted. The landmark is the Lister tubercle at the distal end of the radius. About 1 cm distal to the turbercle is a soft spot that represents the space between the distal radius and the base of the scaphoid. The needle is inserted vertical to the wrist to a depth of 2 cm. If resistance is met, pull back halfway and direct a bit in a distal and radial direction. With the needle in place, the syringe is exchanged (sometimes a needle clamp is needed) for one with local steroid to a volume of 1 mL (Figure 4-23).

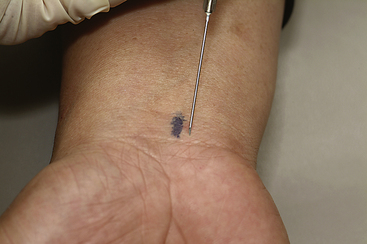

Flexor Tendon (Saldana, 2001)

The tendon to be injected is grasped between the thumb and forefinger of the examiner’s free hand, about 1 cm proximal to the distal palmar crease. The needle is inserted vertical to the palm, aimed in a slightly distal direction. Initially the needle tip may be in the substance of the tendon, so resistance may be encountered. The examiner should withdraw the needle until the steroid flows smoothly and easily. The tendon sheath will balloon in a tubular fashion as the steroid is injected (Figure 4-24).

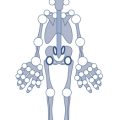

de Quervain Syndrome

The first of six dorsal extensor compartments is at the radial styloid region of the wrist and contains the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons. These tendons are held in place by a vaginal sheath. Inflammation here is known as de Quervain syndrome (Figure 4-25A). Injection is placed into the sheath with a 25 gauge, 5/8 inch needle. A 3 mL Luer lock syringe is filled with 0.5 mL of local steroid and 0.5 mL of local anesthetic. With the wrist in ulnar deviation, the needle is inserted on the radial aspect of the wrist at the radial styloid, about 3 cm proximal to the base of the first metacarpal. The needle is inserted in a slightly proximal direction, aiming toward the elbow, until resistance is met; the needle tip is pulled back slightly until the solution can be injected with little resistance. The sheath should swell slightly with the injection (see Figure 4-25B).

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Injection into the carpal tunnel may relieve compression of the median nerve only temporarily. The palmaris longus tendon insertion is identified at the proximal palmar crease with resisted flexion of the third finger. A 22 gauge, 1 to 1½ inch needle is used with a 3 mL syringe. One mL of local steroid and a half mL of local anesthetic can be used. The needle is inserted just ulnar to the palmaris longus, at the proximal palmar crease, at a 20° to 30° angle to the skin, aimed toward the fourth finger (Figure 4-26). Snagging on a flexor tendon can occur, at which point the needle should be withdrawn slightly and reangled. The needle should be inserted to 2 cm. The anesthetic may leave some tingling in the median nerve distribution for a couple of hours.

First Carpometacarpal Joint

The base of the first metacarpal is identified at the distal end of the anatomical snuffbox between the abductor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) tendons. Flexion of the thumb across the palm makes the joint easier to identify. A 1 mL syringe with a 25 gauge, 5/8 inch needle can be used. About 0.3 mL of local steroid should be mixed with 0.1 mL of local anesthetic. The needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin close to the EPB tendon to avoid the radial artery. Traction on the thumb can sometimes open up the joint space for better access (Figure 4-27).

Distal Radioulnar Joint

The groove between the distal radius and distal ulna can be identified with palpation while passively supinating and pronating the hand. The injection is placed about 1 cm proximal to the groove, where the joint has a synovial pouch. A 3 mL syringe with a 22 gauge, 1 or 1½ inch needle should be used. A half mL of local anesthetic should be mixed with 1 mL of local steroid. The injection needle is inserted perpendicular to the wrist to a depth of about 2.5 cm.

Beckenbaugh R.D. Accurate evaluation and management of the painful wrist following injury. An approach to carpal instability. Orthop. Clin. North Am.. 1984;15:289-306.

De Smet, L., 2002. Classification for congenital anomalies of the hand: the IFSSH classification and the JSSH modification. Genetic Counseling 13 (3), 331–8.

Fam A.G. Aspiration and injection of joints and periarticular tissues: The wrist and hand. In: Klippel J.H., Dieppe P.A., editors. Practical Rheumatology. first ed. London: Mosby; 1995:117-118.

Fam A.G. The wrist and hand. In: Hochberg H., Silman A.J., Smolen J.S., et al, editors. Rheumatology. third ed. London: Mosby; 2003:641-650.

Field J.H. de Quervain’s disease. Am. Fam. Physician. 1979;20:103-104.

Finkelstein H. Stenosing tendovaginitis at the radial styloid process. J. Bone Joint Surg. (Am). 1930;12:509-540.

Lichtman D.M., Noble W.H.III, Alexander C.E. Dynamic triquetrolunate instability: case report. J. Hand Surg. (Am). 1984;9:185-188.

Markison R.E., Kilgore E.S. Hand. In: Davis J.H., editor. Clinical Surgery. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1987:2292-2353.

McMurtry R.Y. The hand. In: Little A.H., editor. The Rheumatological Physical Examination. Orlando, FL: Grune & Stratton; 1986:91-100.

Palumbo C.F., Szabo R.M. Examination of patients for carpal tunnel syndrome: Sensibility, provocative, and motor testing. Hand Clin.. 2002;18:269-277.

Raza K., Lee C.Y., Pilling D., et al. Ultrasound guidance allows accurate needle placement and aspiration from small joints in patients with early inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology. 2003;42:976-979.

Saar J.D., Grothaus P.C. Dupuytren’s disease: An overview. Plast. Reconstruct. Surg.. 2000;106:125-134.

Saldana M.J. Trigger digits: Diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg.. 2001;9:246-252.

Strauch B., de Moura W. Digital flexor tendon sheath: An anatomic study. J. Hand Surg. Am.. 1985;10:785-810.

von Schroeder H.P., Botte M.J. The functional significance of the long extensors and juncturae tendinum in finger extension. J. Hand Surg. [Am]. 1993;18(4):641-647.

von Schroeder H.P., Botte M.J. Functional anatomy of the extensor tendons of the digits. Hand Clin.. 1997;13(1):51-62.

Watson H.K., Ashmead D.I.V., Makhouf M.V. Examination of the scaphoid. J. Hand Surg. (Am). 1988;13(5):657-660.

Wood M.B., Linscheid R.L. Abductor pollicis longus bursitis. Clin. Orthop.. 1973;93:293-296.