Chapter 7. The wrist and hand

CHAPTER CONTENTS

SUMMARY

Repetitive strain injury and work-related upper limb disorder have done much to focus the clinician on the differential diagnosis and causative factors of pain in the wrist and hand.

This chapter takes a pragmatic approach to the identification of specific lesions and suggests localized treatment, which may form a component of overall management. The detailed but relevant anatomy that forms a basis for accurate treatment is presented. Treatment for individual lesions is discussed, with emphasis on the application of principles to less commonly encountered lesions.

ANATOMY

Inert structures

The distal radioulnar joint is a pivot joint between the head of the ulna and the ulnar notch of the radius. Mechanically linked to the superior radioulnar joint, it is responsible for the movements of pronation (85°) and supination (90°).

A triangular fibrocartilaginous articular disc closes the distal radioulnar joint inferiorly and is the main structure uniting the radius and ulna (Palastanga et al 2006). It lies in a horizontal plane, its apex attaching to the ulnar styloid and its base to the lower edge of the ulnar notch of the radius. The disc articulates with the lunate when the hand is in ulnar deviation. It adds to the stability of the joint and acts as an articular cushion for the ulnar side of the carpus, absorbing compression, traction and shearing forces but being prone to degenerative changes (Livengood 1992, Rettig 1994, Wright et al 1994, Steinberg & Plancher 1995).

The movements of pronation and supination rotate the radius around the ulna. Supination is stronger, hence the thread of nuts and screws which are tightened by supination in right-handed people.

There are two rows of carpal bones; on the palmar aspect, from the radial to the ulnar side they are:

scaphoid, lunate, triquetral, pisiform

trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, hamate.

The carpal bones all articulate with their neighbours, except pisiform, which is a separate bone situated on the front of the triquetral. The intercarpal joints are all supported by intercarpal ligaments.

The wrist joint proper is a biaxial, ellipsoid joint between the distal end of the radius and the articular disc, and the proximal row of carpal bones. However, the so-called wrist joint complex includes the midcarpal joint and has mobility as well as stability, which is important for the function of the hand. Movements are extension (passive, 85°), flexion (passive, 85°), ulnar deviation (passive, 45°) and radial deviation (passive, 15°). The close packed position of the wrist joint is full extension.

The joints are surrounded by a fibrous capsule, lined with synovial membrane and reinforced by collateral ligaments. Both collateral ligaments pass from the appropriate styloid process to the carpal bones on the medial and lateral side of the carpus. A fibrocartilaginous meniscus projects into the joint from the ulnar collateral ligament.

The metacarpophalangeal joints are ellipsoid; the interphalangeal joints are hinge joints. Both are supported by palmar and collateral ligaments and the extensor tendons and digital expansions support the dorsal surfaces of the joints. Flexor tendons are contained within fibrous sheaths which have thickened areas known as pulleys which may provide a restriction, producing ‘trigger finger’ (see p. 175). At the wrist and in the hand, the tendons are contained within synovial sheaths (Standring 2009).

The flexor retinaculum, a strong fibrous band, creates a fibro-osseous passage, the carpal tunnel, through which pass the flexor tendons of the digits, the median nerve and vessels. The flexor retinaculum has four points of attachment: the pisiform and hook of hamate medially and the tuberosity of the scaphoid and ridge of trapezium laterally. Its attachment onto the trapezium splits to form a separate compartment for the tendon of flexor carpi radialis. The median nerve enters the carpal tunnel deep to palmaris longus. It shares its compartment of the carpal tunnel with nine tendons comprising the four tendons of flexor digitorum superficialis and the four tendons of flexor digitorum profundus, and flexor pollicis longus. On leaving the carpal tunnel it supplies the thenar muscles before dividing into four or five digital branches.

The trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint (first carpometacarpal joint) is a saddle joint with a loose articular capsule and extensive joint surfaces giving it a wide range of movement. The first metacarpal has been rotated medially for the movement of opposition.

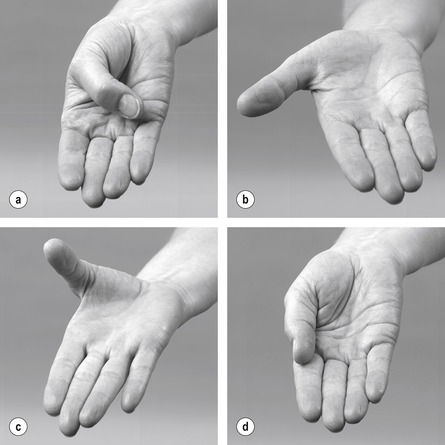

Flexion and extension occur in a plane parallel to the palm of the hand, while abduction and adduction occur in a plane at right angles to the palm of the hand (Fig. 7.1 a–d).

|

| Figure 7.1

Movements of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb: (a) flexion; (b) extension; (c) abduction; (d) adduction.

|

The close packed position of the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint is strong opposition, when great force is transmitted to the joint. The functionally opposed thumb is subjected to compressive stresses which make the joint vulnerable to degenerative osteoarthrosis.

The radial artery passes under abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis, crossing the snuffbox obliquely towards the first dorsal interosseous muscle. Its position should be acknowledged so that it can be avoided when injecting the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint.

Contractile structures

Flexor carpi radialis (median nerve C6–C7) is the most lateral superficial flexor tendon. It passes through its own fibro-osseous compartment on the lateral side of the carpal tunnel, to insert into the base of the second and third metacarpals.

Palmaris longus (median nerve C7–C8) passes over, not under, the flexor retinaculum, to attach to the distal part of the flexor retinaculum and the palmar aponeurosis.

Flexor digitorum superficialis (median nerve C7–C8, T1) lies medial to palmaris longus, but is not as visible because it lies on a slightly deeper plane. In the carpal tunnel the four tendons are contained within the same synovial sheath, with tendons to the third and fourth fingers lying superficial to those to the second and fifth. The tendons divide to provide a passage for flexor digitorum profundus, before continuing on to insert either side of the middle phalanx.

Flexor carpi ulnaris (ulnar nerve C7–C8) is the most medial superficial flexor tendon and can be easily traced onto its insertion into pisiform. The tendon sends slips onwards as the pisohamate and pisofifth-metacarpal ligaments. The pisohamate ligament converts the space between pisiform and the hamate into a tunnel (tunnel of Guyon) for the passage of the ulnar vessels and nerves.

Flexor pollicis longus (median nerve C8, T1) passes through the lateral side of the carpal tunnel and inserts into the palmar aspect of the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb.

Flexor digitorum profundus (medial part supplied by the ulnar nerve; lateral part supplied by the median nerve C8, T1) divides into four tendons which lie deep to flexor digitorum superficialis in the carpal tunnel. They pass through tunnels created by superficialis and attach to the distal phalanx of each finger.

The lumbricals are four small muscles which arise from the flexor digitorum profundus tendons and pass to the radial side of the dorsal digital expansions of each finger. With attachments that link flexor and extensor tendons, they function by flexing the metacarpophalangeal joints and extending the interphalangeal joints. The first two lumbricals are supplied by the median nerve, the third and fourth by the ulnar nerve, C8, T1.

Extensor carpi radialis longus (radial nerve C6–C7) and extensor carpi radialis brevis (posterior interosseous nerve C7–C8) pass deep to the tendons of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis, under the extensor retinaculum, to attach to the radial side of the base of the second and third metacarpals respectively.

Extensor digitorum (posterior interosseous nerve C7–C8) divides into four tendons which pass under the extensor retinaculum to insert into the dorsal digital expansions of the fingers.

Extensor digiti minimi (posterior interosseous nerve C7–C8) inserts into the dorsal digital expansion of the little finger.

Extensor carpi ulnaris (posterior interosseous nerve C7–C8) lies in a groove between the head of the ulna and the styloid process, under the extensor retinaculum. It attaches to the medial side of the base of the fifth metacarpal.

Abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis (posterior interosseous nerve C7–C8) become tendinous and superficial in the lower forearm where they cross the tendons of extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis at the intersection point, a site of potential friction. They occupy the same synovial sheath in the first compartment of the extensor retinaculum and form the lateral border of the anatomical snuffbox. The abductor inserts into the base of the first metacarpal and the extensor into the base of the proximal phalanx. Because of its position, abductor pollicis longus has been considered both anatomically and functionally a radial deviator of the wrist (Elliott 1992a).

Extensor pollicis longus (posterior interosseous nerve C7–C8) deviates around the ulnar side of the dorsal tubercle of the radius, to pass to the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb. It forms the medial border of the anatomical snuffbox.

Extensor indicis (posterior interosseous nerve C7–C8) joins the ulnar side of the extensor digitorum tendon, passing to the index finger.

The dorsal interossei (ulnar nerve C8, T1) are four bipennate muscles arising from adjacent sides of the metacarpal bones and inserting into the dorsal digital expansion and base of the proximal phalanx of the appropriate finger. They are responsible for abducting the fingers from the midline of the middle finger.

The palmar interossei (ulnar nerve C8, T1) are four smaller muscles originating from the palmar aspect of the metacarpal bones and inserting into the dorsal digital expansions of the appropriate finger. They are responsible for adducting the fingers towards the middle finger.

GUIDE TO SURFACE MARKING AND PALPATION

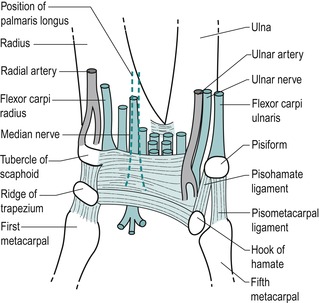

Palmar aspect (Fig. 7.2)

Look for three creases (not distinct in everyone) on the palmar aspect of the lower forearm. The distal wrist crease joins pisiform and the tubercle of the scaphoid, the bones at the heel of the hand (Backhouse & Hutchings 1990), marking the proximal border of the flexor retinaculum. The middle crease joins the two styloid processes, marking the position of the wrist joint line, while the proximal crease (if present) marks the proximal extent of the flexor tendon sheaths.

|

| Figure 7.2

Palmar aspect of the wrist showing position of the flexor retinaculum, its adjacent tendons and nerves.

|

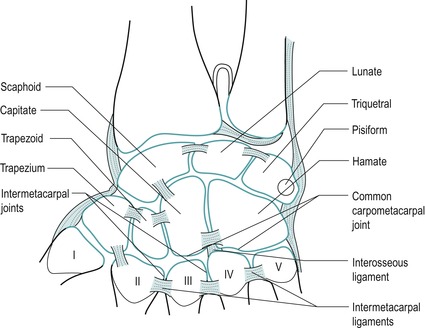

Consider the position of the bones which make up the two rows of carpal bones (Fig. 7.3). From the radial to the ulnar side, an easy way to remember the order is:

| simply learn the parts | scaphoid, lunate, triquetral, pisiform |

| that the carpus has | trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, hamate |

|

| Figure 7.3

Bones of the hand.

From Anatomy and Human Movement by Palastanga N, Field D and Soames R 2006. Reprinted by permission of Elsevier Ltd.

|

Palpate pisiform, the pea-shaped sesamoid bone, which lies at the base of the hypothenar eminence, giving insertion to flexor carpi ulnaris.

Move a thumb approximately 1.5 cm distally and diagonally from pisiform, in the direction of the index finger. Lying roughly in line with the ring finger is the hook of hamate. Palpate deeply and tenderness will confirm its presence.

Radially deviate the wrist to make the tuberosity of the scaphoid more prominent. It lies at the base of the thenar eminence, close to the tendon of flexor carpi radialis. Move a thumb from the tuberosity of the scaphoid, diagonally and distally approximately 1 cm, to lie in line with the index finger, and feel the ridge of the trapezium through the bulk of the thenar eminence. It is best felt with the wrist joint in extension and is tender to deep palpation.

Joining the four points described above – pisiform, hook of hamate, tuberosity of scaphoid and ridge of trapezium – gives the position of the flexor retinaculum, which is approximately the size of your thumb when placed horizontally across the proximal palm (Fig. 7.2).

Identify the superficial forearm flexor tendons as they cross the palmar aspect of the wrist from the radial to ulnar side. Flexor carpi radialis is the most lateral tendon. Palmaris longus passes over the flexor retinaculum and can be brought into prominence by opposing the thumb and little finger with the wrist flexed. Flexor digitorum superficialis, lying in a deeper plane, may not be readily palpable, but flexor carpi ulnaris can be followed down to its insertion onto the pisiform.

Palpate for the radial pulse on the palmar aspect of the lower radius lateral to flexor carpi radialis. The ulnar pulse can be palpated on the lower ulna, lateral to flexor carpi ulnaris.

Consider the position of the median nerve as it enters the carpal tunnel deep to palmaris longus. If palmaris longus is absent, oppose the thumb and little finger and the midline crease produced gives the position of the median nerve.

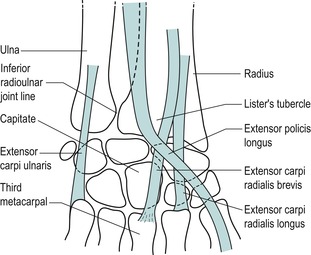

Dorsal aspect (Fig. 7.4)

Pronate the forearm and the head of the ulna can be seen as a rounded elevation in the distal forearm. Palpate to the ulnar side of the head and feel the tendon of extensor carpi ulnaris in the groove between the head of the ulna and the styloid process.

|

| Figure 7.4

Dorsal aspect of the wrist.

|

Palpate the inferior radioulnar joint line, which lies approximately 1.5 cm laterally from the ulnar styloid. Confirm its presence by passively gliding the head of the ulna on the radius and feeling the joint line.

On the lower end of the radius, palpate the dorsal tubercle (of Lister) lying roughly in line with the index finger. The tubercle is grooved on either side by the passing tendons. Extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis pass on its lateral side, while extensor pollicis longus passes on its medial side before taking a 45° turn laterally, where it can be traced to its insertion into the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb.

The capitate is the largest carpal bone and is roughly the size of the patient’s thumb nail. It is wider dorsally and is roughly peg-shaped. It is situated in the centre of the carpus, articulating mainly with the third metacarpal distally, the trapezoid laterally, the hamate medially and the concavity formed by the scaphoid and lunate proximally (Steinberg & Plancher 1995, Standring 2009). To locate the position of the capitate, run your finger proximally down the shaft of the third metacarpal with the wrist in slight flexion and drop over the end into the shallow depression.

Place the wrist in flexion with the thumb relaxed to allow the tendon of extensor pollicis longus to fall out of the way and to expose the base of the metacarpals. Now palpate the insertions of extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis onto the radial side of the base of the second and third metacarpals respectively. The extensor carpi radialis brevis is probably the easier of the two to feel. Palpate the insertion of extensor carpi ulnaris onto the medial side of the base of the fifth metacarpal.

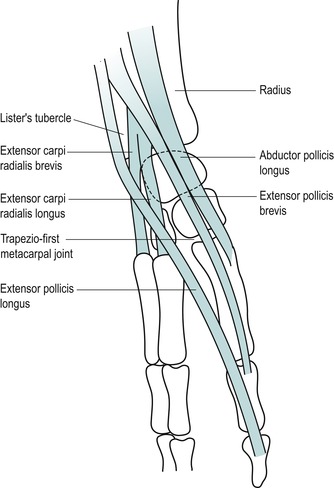

Lateral aspect (Fig. 7.5)

Pronate the forearm and make a fist. The fleshy elevation seen at the distal end of the radius is formed by the musculotendinous junctions of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis as they wind around the lower radius, crossing over the tendons of extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis at the intersection point.

|

| Figure 7.5

Tendons on the lateral aspect of the wrist.

|

Locate the anatomical snuffbox (by extending the thumb) which is bordered by the tendons of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis laterally and by extensor pollicis longus medially. Palpate the radial styloid at the proximal end of the anatomical snuffbox and the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint at the distal end.

Locate the tendons of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis; sometimes a V-shaped gap may be appreciated between the two.

Move the wrist into ulnar deviation and the scaphoid can be palpated distal to the radial styloid; it moves with the hand, whereas the radial styloid does not. The scaphoid can be grasped between your thumb posteriorly in the base of the snuffbox and your index finger anteriorly.

Move distally to palpate the trapezium lying between the scaphoid and the base of the first metacarpal.

Palpate the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint line by running a thumb down the shaft of the first metacarpal into the anatomical snuffbox. Flex and extend the joint to check its location.

Palpate the first dorsal interosseous in the web between index finger and thumb; it can be made more prominent by resisting abduction of the index finger.

COMMENTARY ON THE EXAMINATION

Observation

Before proceeding with the history, a general observation of the patient’s face, posture and gait will alert the examiner to serious abnormalities or injuries. The painful hand may be held in an antalgic position, resting with the fingers parallel to each other and in a degree of flexion, the thumb in a neutral position. Possibly, the arm swing may be absent from the gait pattern and the hand held stiffly against the side or across the body. Difficulty with fine movement may be observed during undressing, indicating a problem with dexterity.

History (subjective examination)

The age, occupation, sports, hobbies and lifestyle of the patient may give an indication of the cause and a possible diagnosis, since most problems in the lower forearm involve arthritis, trauma or overuse. Mobile phone texting and the use of hand-held gaming devices have joined the more traditional causative factors of overuse of scissors and keyboard, etc. The specific activities required in an occupation should be explored to expose the precise movements required of the upper limb, often repetitively for several hours a day. Racquet sports, golf, hockey, etc. can all give rise to symptoms in the wrist and hand resulting from the impact forces and positioning of the upper limb.

The site of pain is usually well localized by the patient, with little spread, since these are peripheral joints and structures lying at the end of their respective dermatomes, with little scope for reference. The presence of paraesthesia or any apparent reference of pain may suggest a more proximal lesion, and all proximal joints must be examined, including the cervical spine. A fractured scaphoid gives localized pain and point tenderness in the anatomical snuffbox, while X-ray investigation may not show evidence of the fracture for several weeks (Livengood 1992).

The onset of the symptoms may be due to trauma, overuse or arthritis. If the onset is traumatic in nature, the possibility of fracture should be eliminated. Frequently, a direct injury involving a fall on the outstretched hand may cause fracture of the scaphoid or subluxation of the capitate or lunate bones, and may also cause a traumatic arthritis with soft tissue swelling and contusion. Indirect injury may also occur from a rotational force or maximal effort in racquet sports (Rettig 1994).

Most injuries at the wrist and hand develop from repetitive overuse. Tendinopathy may result from frequent overstretching or unaccustomed activity. An overuse syndrome occurs when the level of repeated microtrauma exceeds the tissue’s ability to adapt (Rettig 1994). Tensional overload or abnormal shear stresses can cause microtrauma at any point in the musculotendinous or ligamentous unit. The syndromes of carpal tunnel and de Quervain’s (see p. 171 & 174) may be associated with more proximal lesions, such as nerve entrapment or lesions of the cervical spine.

A hyperextension injury to the thumb is a relatively common sporting injury, producing a traumatic arthritis in either the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint or the metacarpophalangeal joint. This may occur in skiing (‘skier’s thumb’) or sports which involve ball-catching, e.g. volleyball, netball or goal-keeping in football.

Arthritis in the hand may be inflammatory, degenerative or traumatic. Rheumatoid arthritis is common in the smaller joints and therefore readily affects the joints of the wrist and hand where deformity is characteristic; it is usually bilaterally symmetrical. Any synovial space can be involved, including the tendon sheaths and bursae, as well as the joints. Juvenile chronic arthritis has less symmetrical joint involvement than adult rheumatoid arthritis.

Primary degenerative osteoarthrosis affects the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joints and the distal interphalangeal joints more readily. These joints are subjected to stress in the functional position and are used through all extremes of range, predisposing them to primary arthritis. Secondary degenerative osteoarthrosis can affect any joint.

The duration of symptoms indicates the stage of the lesion in the inflammatory process. Overuse syndromes have a gradual onset with symptoms present for many months. Rheumatoid arthritis and acute episodes of degenerative osteoarthrosis tend to have periods of remission and exacerbation while traumatic lesions may be of fairly short duration.

The symptoms and behaviour need to be considered. The behaviour of the pain indicates the nature of the lesion, with mechanical lesions eased by rest and aggravated by activity. Overuse lesions are worsened by repetition of the mechanism of trauma. The nature of the pain is also important: is it localized or vaguely diffuse, deep or superficial, sharp, burning, aching, constant or intermittent, getting worse or better, or staying the same?

The other symptoms described by the patient could include paraesthesia. An accurate description of these associated symptoms is relevant to the source of pressure or nerve entrapment. The distribution of pins and needles and whether or not they possess edge and/or aspect helps to determine their origin. Stiffness of the hand may be relevant to arthritis or ligamentous lesions and it is therefore appropriate to know the daily pattern of the symptoms. Heat, coldness, sweating, dryness and other sensory changes may also be relevant, suggesting the vasomotor changes of Raynaud’s disease or reflex sympathetic dystrophy.

An indication of past medical history, other joint involvement and medications will establish whether contraindications to treatment techniques exist. As well as past medical history, establish any ongoing conditions and treatment. Explore other previous or current musculoskeletal problems with previous episodes of the current complaint, any treatment given and the outcome of treatment.

Inspection

Fracture or dislocation commonly occurs with a fall on the outstretched hand and shows obvious bony deformity and swelling. Subluxation, e.g. of the capitate, may be seen as a bump on the dorsum of the hand with the wrist in flexion.

Deformities of the fingers are commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis or may result from forced hyperextension injuries, as in wicket keepers, for example. If an extensor tendon is avulsed or torn from the distal phalanx, a mallet finger occurs with flexion of the distal interphalangeal joint. This can be associated with sporting injuries or may simply occur if the finger is forcibly caught, while making the bed, for example. A bony swelling of the distal interphalangeal joint is a characteristic deformity known as a Heberden’s node, associated with primary degenerative osteoarthrosis.

Degenerative osteoarthrosis of the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint produces a capsular pattern which may draw the thumb into a position of flexion and medial rotation with bony osteophytes obvious at the base of the thumb. Dupuytren’s contracture is a deformity with contraction of the palmar fascia, causing flexion of principally the ring and little fingers. Clubbed fingers may be indicative of systemic disease.

Colour changes, which may indicate circulatory involvement, should be further investigated by palpating for the arterial pulses. The fingers, in particular, can give clues to serious underlying pathology and the colour and shape of the fingers and nails should be noted. Bruising may be apparent, resulting from direct trauma, and may be associated with abrasions on the palm due to a fall on the outstretched hand.

Muscle wasting may be obvious in the flattening of the thenar muscles, producing the ape-like hand with the thumb moving back in line with the other fingers. This indicates involvement of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel or possibly cervical nerve root pressure. Similarly, the ulnar nerve or lower cervical nerve root compression involves the hypothenar eminence, and if the intrinsic muscles are involved a claw hand develops. Involvement of the radial nerve affects the wrist extensors and produces a dropped wrist.

Swelling indicates active inflammation and the wrist may be fixed in the mid-position due to the presence of a joint effusion. Contusions with swelling are due to direct trauma. Excessive friction of the skin causes callus and blister formation, e.g. rowing and gymnastics. Ganglia are mucus-filled cysts, which are commonly seen around the wrist, particularly on the dorsum of the hand. They are common between the second and fourth decades of life (Smith & Wernick 1994) and if symptomatic may be burst or require surgical excision. Rheumatoid nodules may be present.

Palpation

Since these are peripheral joints, palpation for signs of activity is conducted. Temperature changes are assessed and heat indicates an active inflammation, while cold may indicate circulatory problems (Fig. 7.6). It may be appropriate to palpate the ulnar and/or radial pulse (Fig. 7.7). Synovial thickening is usually palpated on the dorsum of the wrist (Fig. 7.8). Swelling is usually observed around the wrist where it may be fusiform, unilateral or bilateral. Other swellings, such as nodules or ganglia, can be palpated to assess whether they are hard or soft.

|

| Figure 7.6

Palpation for heat.

|

|

| Figure 7.7

Palpation for radial pulse.

|

|

| Figure 7.8

Palpation for synovial thickening.

|

State at rest

Before any movements are performed, the state at rest is esta-blished to provide a baseline for subsequent comparison.

Examination by selective tension (objective examination)

The suggested sequence for the objective examination will now be given, followed by a commentary including the reasoning in performing the movements and the significance of the possible findings. Comparison should always be made with the other side.

Inferior radioulnar joint

Wrist joint

• Passive flexion (Fig. 7.11)

|

| Figure 7.11

Passive flexion.

|

• Passive extension (Fig. 7.12)

|

| Figure 7.12

Passive extension.

|

• Passive ulnar deviation (Fig. 7.13)

|

| Figure 7.13

Passive ulnar deviation.

|

• Passive radial deviation (Fig. 7.14)

|

| Figure 7.14

Passive radial deviation.

|

• Resisted flexion (Fig. 7.15)

|

| Figure 7.15

Resisted flexion.

|

• Resisted extension (Fig. 7.16)

|

| Figure 7.16

Resisted extension.

|

• Resisted ulnar deviation (Fig. 7.17)

|

| Figure 7.17

Resisted ulnar deviation.

|

• Resisted radial deviation (Fig. 7.18)

|

| Figure 7.18

Resisted radial deviation.

|

Trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint

• Passive extension and adduction (Fig. 7.19)

|

| Figure 7.19

Passive extension and adduction of the thumb.

|

• Resisted flexion (Fig. 7.20)

|

| Figure 7.20

Resisted thumb flexion.

|

• Resisted extension (Fig. 7.21)

|

| Figure 7.21

Resisted thumb extension.

|

• Resisted abduction (Fig. 7.22)

|

| Figure 7.22

Resisted thumb abduction.

|

• Resisted adduction (Fig. 7.23)

|

| Figure 7.23

Resisted thumb adduction.

|

Interossei

Palpation

• Once a diagnosis has been made, the structure at fault is palpated for the exact site of the lesion

Fingers

• Passive and resisted testing of the fingers is not performed routinely

The inferior radioulnar joint gives pain felt at the wrist and is assessed using two passive movements, passive pronation and supination, looking for pain, range of movement, end-feel and the presence of the capsular pattern. Both rotations normally have an elastic end-feel.

The wrist joint is then assessed by four passive movements, looking for pain, range of movement and end-feel. Passive flexion normally has an elastic end-feel due to tissue tension and passive extension a hard end-feel, while both deviations normally display an elastic end-feel. The presence of the capsular pattern indicates the existence of arthritis; the non-capsular pattern may be due to a subluxed carpal bone, e.g. the capitate, or collateral ligament strain.

The contractile structures at the wrist are assessed by resisted tests looking for pain and power. A positive finding requires palpation of the appropriate anatomical structure to establish the exact site of the lesion. The trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint is assessed by passive application of one combined movement, passive extension and adduction, which is always painful if the capsular pattern is present.

The contractile structures around the thumb are assessed by resisted tests looking for pain and power. Resisted flexion assesses flexor pollicis longus, resisted extension assesses extensor pollicis longus and brevis, resisted abduction assesses abductor pollicis longus and resisted adduction assesses adductor pollicis.

The interossei are assessed by two resisted tests looking for pain and power. Resisted finger abduction assesses the dorsal interossei and resisted finger adduction assesses the palmar interossei.

Passive and resisted movements of the fingers are not part of the routine examination, but included if necessary. Passive movements may establish the capsular patterns described below.

CAPSULAR LESIONS

The presence of the capsular pattern at the joints indicates arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis more readily affects the smaller joints and is seen as symmetrical involvement of the joints in the wrist and hand with deformity characteristic of the condition. Primary degenerative osteoarthrosis affects the trapeziofirst-metacarpal and distal interphalangeal joints more readily. The thumb may be flexed towards the palm of the hand by the contracted anterior joint capsule and the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers may show the characteristic Heberden’s nodes. Trauma may produce traumatic arthritis and fracture of a carpal bone should be eliminated.

Arthritis in the wrist and hand responds to cortico-steroid injection but Grade B mobilization is appropriate for limitation of movement associated with degenerative arthritis; an alternative treatment for the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint is described below.

Inferior (distal) radioulnar joint

The inferior radioulnar joint is most commonly affected by rheumatoid arthritis.

Position the patient with the forearm supported in full pronation. Identify the inferior radioulnar joint line and insert the needle, which may need to be angled, into the joint (Fig. 7.26). Give the injection as a bolus once intracapsular (Fig. 7.27). The patient is advised to maintain a period of relative rest for approximately 2 weeks following injection.

|

| Figure 7.26

Injection of the inferior radioulnar joint.

|

|

| Figure 7.27

Injection of the inferior radioulnar joint showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

Wrist joint

The wrist joint is most commonly affected by rheumatoid arthritis and traumatic arthritis.

Capsular pattern of the wrist joint

• Equal limitation of flexion and extension.

• Eventual fixation in the mid-position.

Position the patient with the wrist supported and the forearm in full pronation (Fig. 7.28). Locate a point of entry, which may be at either side of the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon.

|

| Figure 7.28

Injection of the wrist joint.

|

Give the injection as a bolus once the needle is intracapsular (Fig. 7.29). Alternatively, in the rheumatoid wrist, or if degeneration is sufficient to prevent access to the joint, make two or three needle insertions and pepper the area of synovial thickening with a series of withdrawals and reinsertions. This technique is not comfortable for the patient. The patient is advised to maintain a period of relative rest for approximately 2 weeks following injection.

|

| Figure 7.29

Injection of the wrist joint showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

Trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint

The patient complains of pain and tenderness at the base of the thumb and on using the thumb under compression, e.g. writing, gripping. It is a condition common in middle-aged women (Livengood 1992) and X-ray confirms the diagnosis. An axial compression test applies longitudinal pressure down the shaft of the first metacarpal to grind the articular surfaces together. If positive, it confirms the diagnosis of arthritis and differentiates the condition from de Quervain’s tenosynovitis (see below). A grading system is used to assess the stage of degeneration and to guide the treatment approach. An elastic end-feel on testing the limited movements indicates that the lesion is likely to respond to frictions and stretches to the joint, including distraction. A harder end-feel indicates injection as the treatment of choice. In the persistence of pain with severe limitation of function an orthopaedic opinion is appropriate and surgery may be indicated.

Confirmation of the capsular limitation can be made by asking the patient to put the hands into the prayer position and spreading the thumbs, comparing the two sides.

Position the patient with the hand resting comfortably. The patient can apply a degree of distraction to the affected thumb (Fig. 7.30). Identify the joint line by running your thumb down the first metacarpal into the anatomical snuffbox to locate the joint line. Insert the needle into the joint and give the injection as a bolus (Fig. 7.31). Alternatively, if the thenar eminence is flattened, identify the joint line anteriorly. In either case, osteophyte formation may make the injection difficult. The patient is advised to maintain a period of relative rest for approximately 2 weeks following injection.

|

| Figure 7.30

Injection of the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint.

|

|

| Figure 7.31

Injection of the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

Transverse frictions to the anterior capsular ligament of the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint (Cyriax 1984, Cyriax & Cyriax 1993)

Place the thumb comfortably into extension and adduction. Apply deep transverse frictions with the thumb or index finger reinforced by the middle finger (Fig. 7.32). Direct the friction down onto the anterior capsular ligament and apply the sweep transversely across the fibres. Maintain the technique for 10 min after achieving an analgesic effect. The principles for stretching capsular adhesions can be applied, e.g. Grade B mobilization, and distraction is a useful technique to apply to this joint.

|

| Figure 7.32

Transverse frictions to the anterior capsular ligament of the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint.

|

Finger joints

Identify the affected joint. With knowledge of the position of the tendons and ligaments around it, find a point of convenient access, usually on the dorsal aspect avoiding the digital expansions (Figure 7.33 and Figure 7.35). Angle the needle obliquely and, once intra-articular, give the injection as a bolus (Figure 7.34 and Figure 7.36). The patient is advised to maintain a period of relative rest for approximately 2 weeks following injection.

|

| Figure 7.33

Injection of the metacarpophalangeal joint.

|

|

| Figure 7.34

Injection of the metacarpophalangeal joint showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

|

| Figure 7.35

Injection of the interphalangeal joint.

|

|

| Figure 7.36

Injection of the interphalangeal joint showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

NON-CAPSULAR LESIONS

Subluxed carpal bone

The capitate is particularly prone to dorsal subluxation or displacement because it is roughly peg-shaped, with its dorsal surface slightly wider than its palmar surface. The lunate sits between scaphoid and triquetral, and the lower end of the radius and the articular disc, and may displace anteriorly when the wrist is forced into extension (Norris 2004). Posterior displacements may also occur.

Either bone may displace, but commonly it is the capitate. The mechanism of injury involves a fall on the outstretched hand or repeated compression through the extended wrist, as occurs in gymnastics, for example, causing the capitate to displace dorsally. The patient may complain of pain and limited movement and may be concerned about the bump seen on the dorsum of the hand. Occasionally a subluxed capitate may have been present for a long duration when there is less chance of successful relocation.

On examination there is a non-capsular pattern. Passive extension is painful and limited by a bony block. Passive flexion can usually achieve full range, but the patient experiences pain at the end of range. A bony bump may be obvious on passive flexion, but this should not be confused with the base of the third metacarpal which is also prominent. Diagnosis is dependent upon the appropriate history and the presence of the non-capsular pattern.

The principle of treatment applied here is to relocate the carpal bone by a thrust applied to the capitate under strong traction. It should be emphasized that this is a mobilization technique performed under strong traction, not a manipulation at the end of range. The technique for the capitate mobilization will be explained here, but it can be adapted if another carpal bone is displaced.

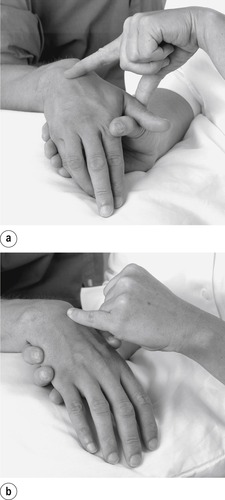

Reduction of the capitate (Saunders 2000)

Locate the capitate by running a thumb down the shaft of the third metacarpal to its base and onto the adjacent displaced capitate (Fig. 7.37). Place one thumb, reinforced by the other, on top of the capitate (Fig. 7.38), and wrap your fingers comfortably around the patient’s thenar and hypothenar eminences (Fig. 7.39).

|

| Figure 7.37

Palpating for the capitate bone at the base of the third metacarpal.

|

|

| Figure 7.38

Thumb position for the reduction of the capitate.

|

|

| Figure 7.39

Finger position for the reduction of the capitate.

|

Placing your little finger into the web between the patient’s thumb and index finger will prevent you from flexing the patient’s wrist during the technique.

Position the patient’s proximal row of carpal bones level with the edge of the couch. Instruct an assistant to fix this proximal row of carpal bones with the web of the hand parallel to the edge of the couch and reinforced with the other hand, to give counterpressure (Fig. 7.40).

|

| Figure 7.40

Assistant’s hand position for the reduction of the capitate.

|

Place your feet directly under the patient’s hand and lean back to apply strong traction (Fig. 7.41). Allow this traction to establish for a few seconds to separate the two rows of carpal bones. Apply a sharp thrust downwards on the capitate to assist its relocation.

|

| Figure 7.41

Body position for the reduction of the capitate.

|

Re-examine the patient to assess the results and repeat if necessary.

If pain persists after relocation, the ligaments surrounding the capitate may be treated with deep transverse frictions (Fig. 7.42a,b).

|

| Figure 7.42

Transverse frictions to the capitate ligaments: (a) horizontaly for vertical fibres and (b) vertically for horizontal fibres.

|

Collateral ligaments at the wrist joint

The collateral ligaments may be sprained by a trau-matic overstretching of the wrist joint or by repetitive microtrauma due to overuse. The condition may also be associated with rheumatoid arthritis. The patient complains of localized pain, and stretching the ligament by passive movement in the opposite direction reproduces this pain. The ligament is tender to palpation.

Radial collateral ligament sprain produces pain on passive ulnar deviation and a sprained ulnar collateral ligament produces pain on passive radial deviation. Either lesion may be treated by applying the principles of corticosteroid injection using a peppering technique, or by deep transverse frictions, having placed the hand in a suitable position to gain access to the ligament (Figure 7.43, Figure 7.44, Figure 7.45, Figure 7.46, Figure 7.47 and Figure 7.48).

|

| Figure 7.43

Injection of the radial collateral ligament.

|

|

| Figure 7.44

Injection of the radial collateral ligament showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

|

| Figure 7.45

Injection of the ulnar collateral ligament.

|

|

| Figure 7.46

Injection of the ulnar collateral ligament showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

|

| Figure 7.47

Transverse frictions to the radial collateral ligament.

|

|

| Figure 7.48

Transverse frictions to the ulnar collateral ligament.

|

Carpal tunnel syndrome

The mechanism of the lesion is uncertain, but involves some compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel. Mechanical and vascular factors are believed to be involved, with inflammation increasing the size of structures lying within the tunnel, causing swelling and compression, or with scarring affecting the perineural circulation (Anderson & Tichenor 1994). The muscles of the thenar eminence may be affected by denervation, abductor pollicis brevis in particular, causing the thumb to fall back into line with the other digits and flattening of the thenar eminence.

Anything which reduces the already tight space in the tunnel compresses the nerve. Intrinsic factors include inflammation and swelling of any structure within the tunnel, or reduction of the size of the tunnel itself: tenosynovitis, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, obesity, rheumatoid arthritis and acromegaly (Kumar & Clark 2002). External factors include trauma, pressure, repetitive occupational or leisure activities, repeated gripping or squeezing, excessive vibration from heavy machinery, keyboard use, knitting, woodworking, using power tools, or racquet sports. Bland (2007) refers to a strong genetic predisposition to carpal tunnel syndrome. It occurs more commonly in women between the ages of 40 and 60, peaking in the late 50s (Norris 2004, Bland 2007).

The presenting symptoms and signs of carpal tunnel syndrome are variable. The patient usually complains of an aching, burning sensation, with tingling or numbness of the finger tips. Paraesthesia is experienced in the radial three and a half digits on the palmar surface. About 70% of patients experience numbness at night and 40% complain of pain radiating proximally into the lower forearm with simultaneous paraesthesia felt in the fingers (Smith & Wernick 1994). The symptoms may wake patients at night and they may gain relief by shaking or rubbing the hands (Cailliet 1990). Patients may complain of a loss of dexterity and sensitivity, with clumsiness of hand function.

On examination, flattening of the thenar eminence may be observed if median nerve compression has occurred. Objective sensory loss may be found in prolonged cases of compression with weakness of the thenar muscles, especially abductor pollicis brevis, if the motor branch is involved.

Bland (2007) observes that Tinel’s sign and Phalen’s test are the most widely and recognized tests for confirming the diagnosis, although it should be recognized that these tests are not perfect diagnostic indicators. False-negative and false-positive rates have been reported of between 25 and 50% (see Hattam & Smeatham 2010). Nerve conduction studies show diminished nerve velocity across the wrist in 90% of patients who go on to have proven nerve compression at surgery (Smith & Wernick 1994).

Tinel’s sign for median nerve compression in the carpal tunnel involves tapping the flexor retinaculum. It is positive if pins and needles are elicited in the radial three and a half digits (Hoppenfeld 1976, Hartley 1995, Ekim et al 2007).

Phalen’s test applies compression to the median nerve in the carpal tunnel, achieved by maintaining maximum wrist flexion. The test is positive if pins and needles are reproduced. A normal hand would develop tingling if this position were maintained for 10 min or more; a patient with carpal tunnel syndrome will report the onset of pain, numbness and tingling within 1–2 min. If symptoms are not reproduced within 3 min the test may be considered to be negative (Hoppenfeld 1976, Cailliet 1990, Vargas Busquets 1994, Hartley 1995, Ekim et al 2007).

The ‘link test’ can be applied to assess muscle strength; the thumb and individual fingers are opposed in turn and the examiner attempts to break the link, which should not be possible if the patient possesses normal muscle power.

Examination of the cervical spine and neural tension testing should be conducted if there is any suspicion that the lesion lies more proximally.

Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome

The causative factors should be discussed with the patient and attempts made to avoid repetitive actions. Symptomatic relief may be gained from a corticosteroid injection. The patient may be fitted with a wrist support splint to wear at night, to avoid flexion, especially during pregnancy. A review conducted by Marshall et al (2007) concluded that local corticosteroid injection for carpal tunnel syndrome provided greater improvement in symptoms 1 month after injection compared to placebo and significantly greater improvement than oral corticosteroid for up to 3 months. There was little consensus on the dose injected, however. If injection is unsuccessful or relief is short-term only, surgical release of the flexor retinaculum may be considered. Significant weakness of the thenar muscles will usually be an indication for surgery.

Position the patient with the wrist supported in extension. Choose a point of entry between the distal and middle wrist creases on the ulnar side of palmaris longus. If palmaris longus is absent, oppose the thumb and little finger to produce a midline crease as a guide and keep to the ulnar side (Fig. 7.49). Angle the needle parallel to and between the flexor tendons, until it is under the flexor retinaculum, and give the injection as a bolus within the tunnel (Fig. 7.50). Be careful to check that there is no paraesthesia before injecting to avoid injury to the median nerve. The patient is advised to maintain a period of relative rest for approximately 2 weeks following injection.

|

| Figure 7.49

Injection of the carpal tunnel.

|

|

| Figure 7.50

Injection of the carpal tunnel showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

Fibrocartilage tears and meniscal lesions

A triangular fibrocartilaginous disc is related to the distal radioulnar joint inferiorly and a fibrocartilaginous meniscus projects into the wrist joint from the ulnar collateral ligament. These intra-articular structures are prone to degenerative changes, tears and occasionally displacement. Trauma, such as a fall on the outstretched hand or repetitive joint overloading, can cause degeneration and tears. Central or radial tears are the most common (Rettig 1994).

A mechanical lesion involving a tear or displacement of any part of the intra-articular complex presents with pain and clicking felt on the ulnar side of the wrist. On examination the clicking may be appreciated by the examiner palpating the wrist while simultaneously pronating and supinating the forearm. Passive ulnar deviation may reproduce the pain, and point tenderness may be felt just distal to the ulnar styloid. To confirm diagnosis of a mechanical lesion of the intra-articular complex, the wrist is placed into extension and ulnar deviation, and axial compression is applied to the ulnar side of the wrist while the wrist is passively circumducted (Hattam & Smeatham 2010).

Treatment may involve strong distraction to reduce possible displacement, or the patient may be referred for arthroscopy and excision.

Trigger finger or thumb

Trigger finger or thumb is a snapping phenomenon producing a painful catch as a flexor tendon is caught at a thickened pulley of the sheath during flexion and then released during forced extension (Smith & Wernick 1994, Murphy et al 1995). Palmar trauma or irritation can cause thickening of the tendon, sheath or annular pulley and a palpable nodule may exist. Some 35% of cases involve the flexor pollicis longus tendon and 50% involve the middle or ring finger flexor tendons (Smith & Wernick 1994). The condition may be secondary to systemic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes mellitus.

Treatment by corticosteroid injection can be curative, restoring painless, smooth full range of movement to the digit (Murphy et al 1995).

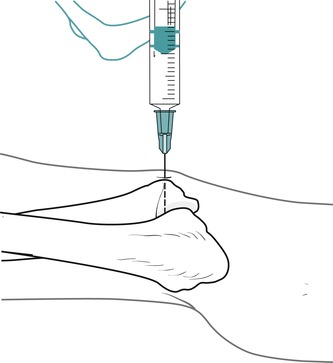

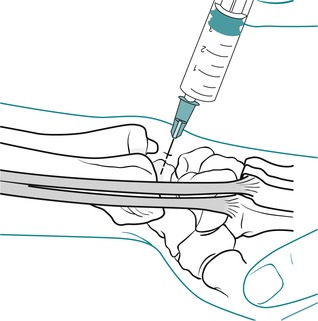

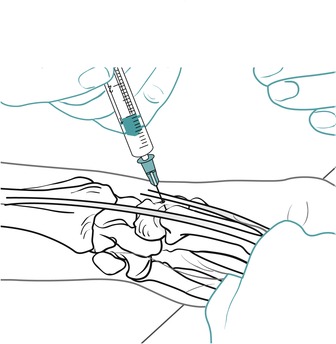

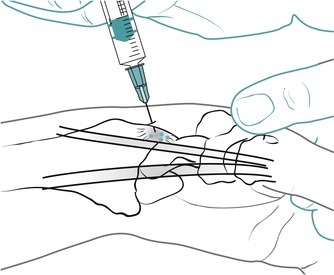

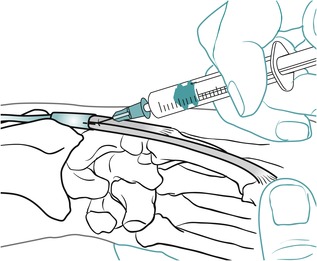

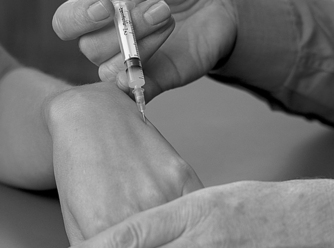

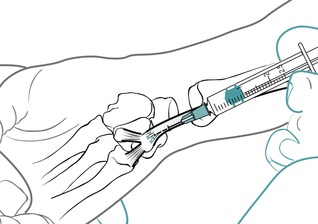

Insert the needle towards the thickened nodule of the affected tendon on the palmar surface. Angle the needle approximately 45°, distally or proximally, with the bevel of the needle parallel to the tendon. Avoid injecting into the tendon and nodule itself by withdrawing back from the substance of the tendon slightly until a loss of resistance is appreciated, and deliver the injection slowly as a bolus (Figure 7.51 and Figure 7.52). The patient is advised to maintain a period of relative rest for approximately 2 weeks following injection.

|

| Figure 7.51

Injection for trigger finger.

|

|

| Figure 7.52

Injection for trigger finger showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

CONTRACTILE LESIONS

Tendinopathy at the teno-osseous junction of a tendon and tenosynovitis affecting the tendon in its sheath, as it runs under either the flexor or extensor retinacula, are common lesions found at the wrist and hand. Overuse is the most likely cause of the lesion, which may be tendinopathy or tenosynovitis of a single unit, or part of an overall more complex syndrome known as repetitive strain injury or work-related upper limb disorder.

Tendinopathy at the teno-osseous junction can be treated by injection using a peppering technique or transverse frictions.

Tenosynovitis can be treated by transverse frictions applied with the tendon on a stretch to restore the gliding function of the tendon sheath, graded according to the irritability or severity of the lesion, or corticosteroid injection delivered between the tendon and its sheath. All sites are subjected to relative rest from overusing or aggravating factors following treatment.

Common contractile lesions will be discussed.

De Quervain’s tenosynovitis

This common condition, originally described in 1895, is tenosynovitis involving the tendons of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis in the first extensor compartment at the wrist (Elliott 1992a, Livengood 1992, Rettig 1994, Klug 1995).

Uncomplicated inflammation of the shared synovial sheath is known as de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. If the shared sheath is thickened due to scarring associated with chronic inflammation it becomes stenotic (Marini et al 1994); it is then known as de Quervain’s stenosing tenosynovitis. Occasionally a ganglion is associated with the condition, especially if it is chronic (Tan et al 1994, Klug 1995).

Women are more commonly affected and the condition may be bilateral in up to 30% of patients (Klug 1995). Onset is occasionally due to direct trauma but more usually due to repetitive occupational or leisure activities. Shea et al (1991) reported a case of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis associated with repeated gear-shifting in a mountain bike rider. Gout or rheumatoid arthritis may be associated conditions and Chen & Eng (1994) described a case of early tuberculous tenosynovitis mimicking de Quervain’s tenosynovitis.

Pain is felt on the radial side of the wrist with point tenderness over the radial styloid. Pain is aggravated by movements into ulnar deviation, forced flexion/adduction of the thumb and wringing movements of the hand, especially into ulnar deviation. Crepitus may be audible during movements of the wrist.

On examination a local, thickened swelling may be obvious, especially to palpation (Anderson & Tichenor 1994), with the pain reproduced on resisted thumb abduction and extension. Passive movements of the thumb also reproduce the pain as the tendon is pushed or pulled through the thickened, inflamed sheath.

The axial grind test for arthritis of the trapeziofirst-metacarpal joint should be negative in de Quervain’s tenosynovitis.

Finkelstein’s test, placing the patient’s thumb in the palm of the hand and positioning the hand into ulnar deviation, produces excruciating pain over the radial styloid. If positive it is pathognomic of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis (Livengood 1992, Elliott 1992b, Rettig 1994, Hattam & Smeatham 2010).

The treatment of choice for de Quervain’s stenosing tenosynovitis is a corticosteroid injection. Weiss et al (1994) compared the use of corticosteroid and lidocaine (lignocaine) with splinting alone and established better results in the injection group. If the symptoms are not completely cleared, the injection may be repeated.

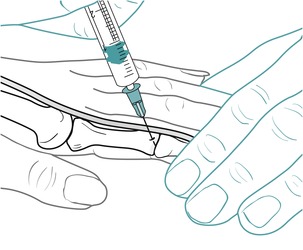

Suggested needle size: 25G × 5/8 in (0.5 ×16 mm) orange needle

Dose: 10 mg triamcinolone acetonide in a total volume of 1 mL

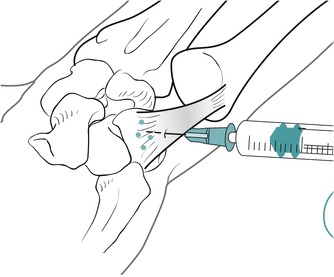

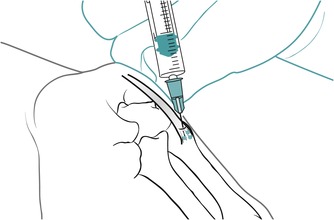

Position the patient in sitting, with the wrist supported, holding the thumb in a degree of flexion and the wrist in ulnar deviation and slight extension. Identify the tendons of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis and the V-shaped gap between them at the base of the first metacarpal. Insert the needle between and parallel to the two tendons (Fig. 7.53). Give the injection as a bolus into the shared sheath (Fig. 7.54). If the injection has been correctly placed a slight swelling will be seen around the tendons. The patient is advised to maintain a period of relative rest for approximately 2 weeks following injection.

|

| Figure 7.53

Injection for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis.

|

|

| Figure 7.54

Injection for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

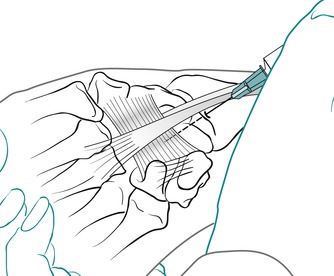

Transverse frictions for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis

Alternatively, deep transverse frictions may be applied. Place the thumb into flexion and ulnar deviation at the wrist, to put the tendons on the stretch (Fig. 7.55). Direct the frictions down onto the tendons using two fingers side by side and sweep transversely across the fibres. Apply 10 min of deep transverse frictions after the analgesic effect is achieved. Relative rest is advised where functional movements may continue, but no overuse or stretching until pain-free on resisted testing. A splint to support the thumb in the resting position may be helpful.

|

| Figure 7.55

Transverse frictions for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis.

|

As de Quervain’s tenosynovitis is a chronic lesion, it may form part of a syndrome involving occupational overuse and it may be necessary to include a full examination of the cervical spine and upper limb, including neural tension. All components of the condition should be treated appropriately.

Intersection syndrome or oarsman’s wrist

The intersection, or crossover, point between the two sets of tendons (abductor pollicis longus/extensor pollicis brevis and extensor carpi radialis longus/brevis) occurs at a point on the radius approximately 4 cm proximal to the wrist (Livengood 1992, Klug 1995). It is a point of potential friction between the structures as they exert tension in different directions. This could produce tenosynovitis of the tendons as they pass under the extensor retinaculum or, more commonly, inflammation of the musculotendinous junction in the lower forearm.

Cyriax (1982) referred to this as myosynovitis with crepitation of the muscle bellies, a condition which occasionally also affects the tibialis anterior muscle. Brukner & Khan (2007) attribute the condition to bursitis between the two sets of tendons. The condition is provoked by overuse and the patients usually present with acute pain and the classical signs of inflammation, heat, redness, swelling and disturbed function. Crepitation is usually audible on movement but pain makes objective testing difficult.

Transverse frictions for intersection syndrome

Treatment begins immediately with protection, rest and ice to control pain and inflammation. Gentle transverse frictions are given, ideally on a daily basis, and the patient usually recovers relatively quickly.

Position the patient comfortably on a pillow. Identify the area of tenderness, which is obvious on the lower radial aspect of the forearm. Place a thumb along the length of the painful tendons and by abduction and adduction of the thumb or pronation and supination of your forearm, impart the frictions transversely across the fibres (Fig. 7.56). Alternatively, all four finger pads can be placed at right angles across the tendons to impart the frictions transversely across the fibres. Begin gently to achieve the analgesic effect, then follow this with approximately six good sweeps to produce movement. Relative rest is advised where functional movements may continue within the pain-free range, but no overuse or stretching until pain-free on resisted testing. This condition is commonly provoked again by overuse and the patient may need instruction in manual handling tasks and activity modification.

|

| Figure 7.56

Transverse frictions for intersection syndrome.

|

Extensor carpi ulnaris tendinopathy

After de Quervain’s, tenosynovitis of extensor carpi ulnaris is the next most common tenosynovitis at the wrist (Klug 1995). Tenosynovitis or tendinopathy at the teno-osseous junction is usually due to repetitive overuse, sometimes occurring in the non-dominant hand of the tennis player who uses a double-handed backhand when the ‘take back’ involves an extreme position of ulnar deviation (Rettig 1994).

Direct trauma may cause subluxation of the tendon from the groove between the head of the ulna and the styloid process (Livengood 1992, Rettig 1994). The patient complains of pain and clicking on the ulnar side of the wrist. When the extended wrist is actively taken from radial to ulnar deviation, the subluxation of the tendon can be observed and this will help differentiate the condition from a triangular fibrocartilage or meniscal lesion.

Treatment applies the techniques of corticosteroid injection, either injecting between the tendon and sheath in tenosynovitis or peppering the insertion at the base of the fifth metacarpal (Figure 7.57 and Figure 7.58). Alternatively, transverse frictions can be used, with the tendon on the stretch in tenosynovitis (Fig. 7.59) and against the insertion for the teno-osseous junction.

|

| Figure 7.57

Injection for extensor carpi ulnaris at teno-osseous site.

|

|

| Figure 7.58

Injection for extensor carpi ulnaris at teno-osseous site showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

|

| Figure 7.59

Transverse frictions for extensor carpi ulnaris tenosynovitis.

|

Extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis tendinopathy

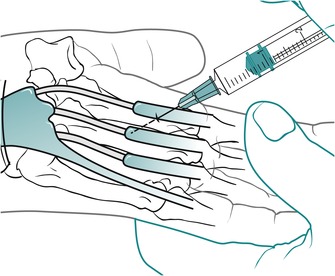

The lesion is usually at the teno-osseous junction where it is due to repetitive overuse, or it may be associated with a bony metacarpal protuberance or boss (Rettig 1994, Bergman 1995). Pain is felt on resisted wrist extension and resisted radial deviation.

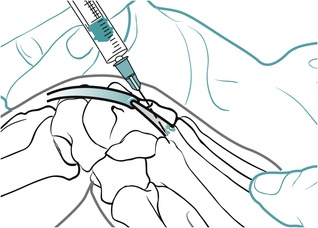

The principles of corticosteroid injection or transverse frictions are applied to treat the lesion. Position the patient with the wrist in flexion to expose the base of the metacarpals and to allow the long extensor tendon to the thumb to fall out of the way. Identify the site of the lesion by palpation at the radial side of the base of either the second or third metacarpals (Fig. 7.60). Deliver the corticosteroid injection by a peppering technique (Fig. 7.61), or direct the transverse frictions down on to the insertion and sweep transversely across the fibres (Fig. 7.62).

|

| Figure 7.60

Injection for extensor carpi radialis longus or brevis tendons at teno-osseous site.

|

|

| Figure 7.61

Injection for extensor carpi radialis longus or brevis tendons at teno-osseous site showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

|

| Figure 7.62

Transverse frictions to extensor carpi radialis longus or brevis tendons at teno-osseous site.

|

Flexor carpi ulnaris tendinopathy

Insertional tendinopathy can occur at the proximal or distal teno-osseous junctions at the pisiform. Treatment consists of a corticosteroid injection delivered by a peppering technique into the lesion (Figure 7.63 and Figure 7.64) or transverse frictions.

|

| Figure 7.63

Injection for flexor carpi ulnaris tendinopathy, proximal site.

|

|

| Figure 7.64

Injection for flexor carpi ulnaris tendinopathy, proximal site, showing direction of approach and needle position.

|

Remember the position of the ulnar nerve, lying just lateral to the tendon, so that you can avoid it if injecting.

If applying transverse frictions at the proximal site, direct your thumb down onto pisiform (Fig. 7.65). With the patient’s little finger flexed, to relax the hypothenar eminence, apply transverse frictions to the distal site (Fig. 7.66). Sweep transversely across the fibres at either site.

|

| Figure 7.65

Transverse frictions to flexor carpi ulnaris tendinopathy, proximal site.

|

|

| Figure 7.66

Transverse frictions to flexor carpi ulnaris tendinopathy, distal site.

|

Interosseous muscle lesions

Strain of the dorsal interossei more commonly affects musicians and tennis players, for example. The patient presents with a vague pain at the metacarpophalangeal joint or between the metacarpals which is exacerbated by repeated gripping (Rettig 1994). Pain will be reproduced by resisted abduction of the appropriate finger.

The treatment of choice is transverse frictions. Palpation will determine the site, but it is often from the origin of the interosseous muscle on one metacarpal. Direct your pressure against the metacarpal and perform the sweep parallel to the shaft (Fig. 7.67).

|

| Figure 7.67

Transverse frictions to the dorsal interossei.

|

REFERENCES

Anderson, M.; Tichenor, C.J., A patient with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis: a case study report using an Australian approach to manual therapy, Phys. Ther. 74 (1994) 314–326.

Backhouse, K.M.; Hutchings, R.T., A Colour Atlas of Surface Anatomy – Clinical and Applied. ( 1990)Wolfe Medical, London.

Bergman, A.G., Synovial lesions of the hand and wrist., MRI Clin. N. Am. 3 (1995) 265–279.

Bland, J., Carpal tunnel syndrome, Br. Med. J. 335 (2007) 343–346.

Brukner, P.; Khan, K., Clinical Sports Medicine. ( 2007)McGraw Hill, Sydney.

Cailliet, R., Soft Tissue Pain and Disability. 2nd edn ( 1990)F A Davis, Philadelphia.

Chen, W.-S.; Eng, H.-L., Tuberculous tenosynovitis of the wrist mimicking de Quervain’s disease., J. Rheumatol. 21 (1994) 763–765.

Cyriax, J., 8th ednTextbook of Orthopaedic Medicine. vol. 1 ( 1982)Baillière Tindall, London.

Cyriax, J., 11th ednTextbook of Orthopaedic Medicine. vol. 2 ( 1984)Baillière Tindall, London.

Cyriax, J.; Cyriax, P., Cyriax’s Illustrated Manual of Orthopaedic Medicine.. ( 1993)Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford.

Ekim, A.; Armagan, O.; Tascioglu, F.; et al., Effect of low level laser therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients with carpal tunnel syndrome, Swiss Med. Wkly. 137 (23–24) ( 2007) 347–352.

Elliott, B.G., Abductor pollicis longus – a case of mistaken identity, J. Hand Surg. 17B (1992) 476–478.

Elliott, B.G., Finkelstein’s test: a descriptive error that can produce a false positive, J. Hand Surg. 17B (1992) 481–482.

Hartley, A., Practical Joint Assessment – Lower Quadrant. 2nd edn. ( 1995)Mosby, London.

Hattam, P.; Smeatham, A., Special Tests in Musculoskeletal Examination. ( 2010)Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Hoppenfeld, S., Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities. ( 1976)Appleton Century Crofts, Norwalk, Connecticut.

Klug, J.D., MR diagnosis of tenosynovitis about the wrist, MRI Clin. N. Am. 3 (1995) 305–312.

Kumar, P.; Clark, M., Clinical Medicine. 5th edn ( 2002)Baillière Tindall, London.

Livengood, L., Occupational soft tissue disorders of the hand and forearm, Wis. Med. J. 91 (10) ( 1992) 583–584.

Marini, M.; Boni, S.; Pingi, A.; et al., De Quervain’s disease: diagnostic imaging, Chir. Organi. Mov. 79 (1994) 219–223.

Marshall, S.; Tardif, G.; Ashworth, N., Local corticosteroid injection for carpal tunnel syndrome, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. ( 2)) ( 2007).

Murphy, D.; Failla, J.M.; Koniuch, M.P., Steroid versus placebo injection for trigger finger, J. Hand Surg. 20A (1995) 628–631.

Norris, C.M., Sports Injuries: Diagnosis and Management for Physiotherapists. 2nd edn ( 2004)Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford.

Palastanga, N.; Field, D.; Soames, R., Anatomy and Human Movement. 5th edn ( 2006)Butterworth-Heinemann, Edinburgh.

Rettig, A., Wrist problems in the tennis player, Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 26 (1994) 1207–1212.

Saunders, S., Orthopaedic Medicine Course Manual. ( 2000)Saunders, London.

Shea, K.G.; Shumsky, I.B.; Shea, O.F., Shifting into wrist pain – de Quervain’s disease and off-road mountain biking, Physician Sports Med. 19 (1991) 59–63.

Smith, D.L.; Wernick, R., Common nonarticular syndromes in the elbow, wrist and hand, Postgrad. Med. 95 (1994) 173–188.

Standring, S., Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 40th edn ( 2009)Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Steinberg, B.D.; Plancher, K.D., Clinical anatomy of the wrist and elbow, Clin. Sports Med. 14 (1995) 299–313.

Tan, M.Y.; Low, C.K.; Tan, S.K., De Quervain’s tenosynovitis and ganglion over first dorsal extensor retinacular compartment, Ann. Acad. Med. 23 (1994) 885–886.

Vargas Busquets, M.A.V., Historical commentary: the wrist flexion test Phalen’s sign, J. Hand Surg. 19 (1994) 521.

Weiss, A.P.; Akelman, E.; Tabatabai, M., Treatment of de Quervain’s disease., J. Hand Surg. 19A (1994) 595–598.

Wright, T.W.; del Charco, M.; Wheeler, D., Incidence of ligament lesions and associated degenerative changes in the elderly wrist, J. Hand Surg. 10A (1994) 313–318.