17 The Visual System

The visual system is the most studied sensory system, partly because we are such a visually oriented species and partly because of its relative simplicity. In addition, the visual pathway is highly organized in a topographical sense, so even though it stretches from the front of your face to the back of your head, damage anyplace causes deficits that are relatively easy to understand.

The Eye Has Three Concentric Tissue Layers and a Lens

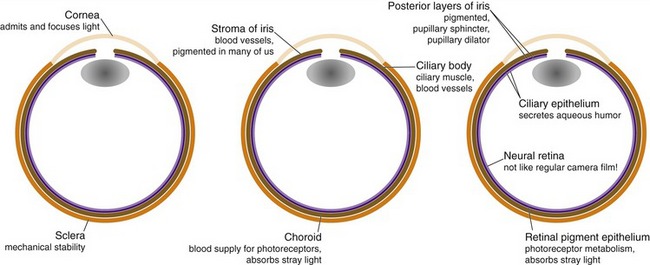

Vertebrate eyes perform functions analogous to those performed by cameras, but do so using three roughly spherical, concentric tissue layers either derived from or comparable to the dura mater, the pia-arachnoid, and the CNS (Fig. 17-1). The thick, collagenous outer layer forms the sclera—the white of the eye—and continues anteriorly as the cornea and posteriorly as the dural optic nerve sheath. The middle layer is loose, vascular connective tissue that forms the pigmented choroid that lines the sclera; it continues anteriorly as the vascular core of the ciliary body, the ciliary muscle, and most of the iris. The innermost layer, itself a double layer because of the way the eye develops (THB6 Figure 17-1, p. 416), forms the neural retina (closer to the interior of the eye) and the retinal pigment epithelium (adjacent to the choroid); it continues anteriorly as the double-layered epithelial covering of the ciliary body and the posterior surface of the iris. Suspended inside the eye, and not really part of any of these tissue layers, is the lens.

The Cornea and Lens Focus Images on the Retina

There’s a big change in refractive index at the interface between air and the front of the cornea, so this is where most of the focusing happens. The lens contributes less because there’s much less change in refractive index going from aqueous humor to lens or from lens to vitreous humor. The major importance of the lens is in adjusting the focus of the eye during accommodation for near vision (see Fig. 17-9 later in this chapter). Contraction of the ciliary muscle relaxes some of the tension on the capsule suspending the lens, allowing the lens to get fatter and the eye to focus on near objects.

The Iris Affects the Brightness and Quality of the Image Focused on the Retina

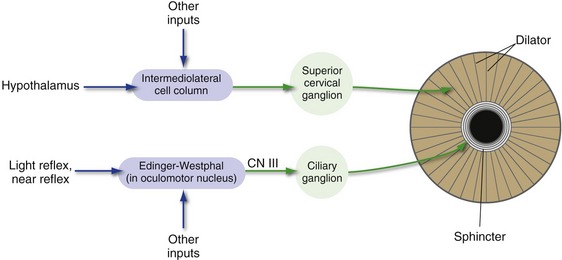

The pigmented posterior epithelial layers of the iris prevent light from getting into the eye except through the pupil, so regulating the size of the pupil regulates the amount of light reaching the retina (although neural changes in the retina are much more important for regulating the sensitivity of the eye). The pupillary sphincter, innervated by the oculomotor nerve via the ciliary ganglion, makes the pupil smaller (see Figs. 17-7 and 17-8 later in this chapter). The pupillary dilator, innervated by upper thoracic sympathetics via the superior cervical ganglion, makes the pupil larger.

The Retina Contains Five Major Neuronal Cell Types

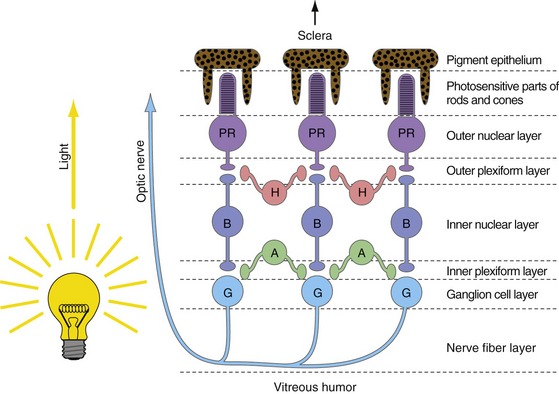

The job of the retina is to convert patterns of light into trains of action potentials in the optic nerve. It does this using five basic cell types (Fig. 17-2), whose cell bodies are arranged in three layers (outer and inner nuclear layers, ganglion cell layer). Alternating with these three layers of cell bodies are an outer and an inner plexiform layer where the synaptic interactions occur. In the outer plexiform layer, photoreceptor cells (rods and cones) bring visual information in, bipolar cells take it out, and horizontal cells mediate lateral interactions. In the inner plexiform layer bipolar cells bring visual information in, ganglion cells take it out (their axons form the optic nerve), and amacrine cells mediate lateral interactions.

Standard descriptions of the retina as a 10-layered structure also include a row of junctions between adjacent photoreceptors (outer limiting membrane), the layer of ganglion cell axons (nerve fiber layer), and the basal lamina on the vitreal surface of the retina (inner limiting membrane). Oddly enough, the layers are arranged so that the last part of vertebrate neural retinas reached by light is the photosensitive parts of the rod and cone cells, embedded in processes of pigment epithelial cells.

Retinal Neurons Translate Patterns of Light into Patterns of Contrast

Photopigments Are G Protein–Coupled Receptors That Cause Hyperpolarizing Receptor Potentials

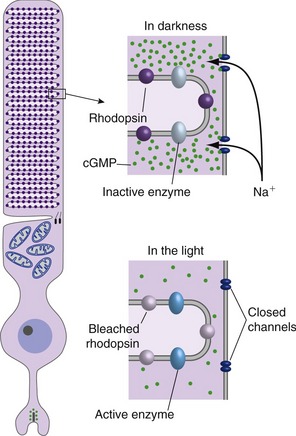

Phototransduction is a lot like G protein–coupled synaptic transmission (Fig. 17-3); the equivalent of the postsynaptic receptor protein is opsin, which in the dark binds a particular stereoisomer of a vitamin A derivative (11-cis-retinal). Absorption of a photon by a visual pigment molecule has only one direct effect: It photoisomerizes the 11-cis-retinal, changing the way it fits with opsin. This in turn activates nearby G proteins, each of which activates an enzyme that hydrolyzes cytoplasmic cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). The surface membranes of photoreceptor outer segments contain cGMP-gated cation channels, so cGMP hydrolysis causes the channels to close and the photoreceptor to hyperpolarize. Hence, light for a photoreceptor is a lot like neurotransmitter release at an unusual G protein–coupled inhibitory synapse—in the light G proteins dissociate, the concentration of a second messenger changes, and cation channels close.

Ganglion Cells Have Center-Surround Receptive Fields

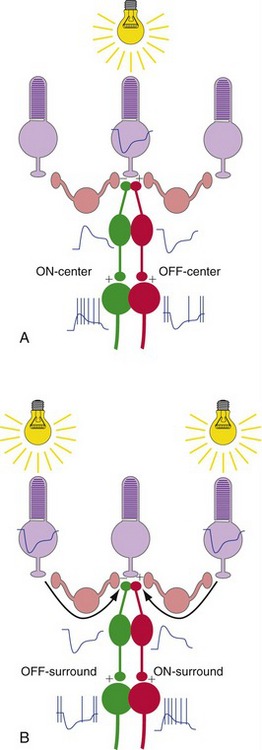

The centers of ganglion cell receptive fields result from “straight-through” transmission from receptors to bipolar cells to ganglion cells (Fig. 17-4). The surrounds result from lateral interactions mediated by horizontal and amacrine cells (especially horizontal cells).

Half of the Visual Field of Each Eye Is Mapped Systematically in the Contralateral Cerebral Hemisphere

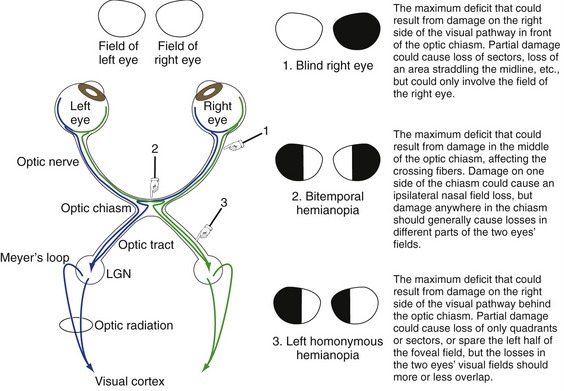

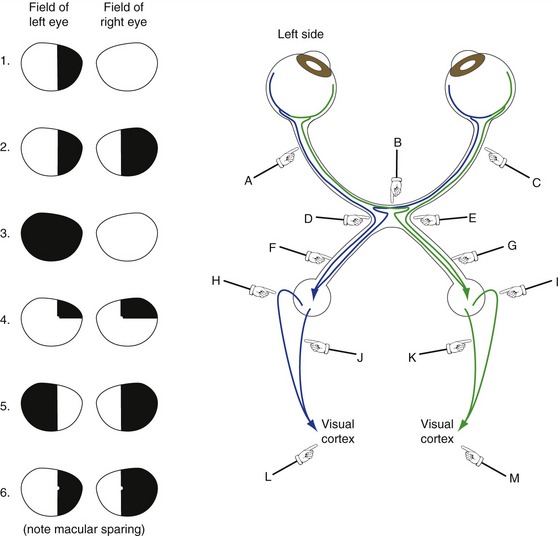

Damage at Different Points in the Visual Pathway Results in Predictable Deficits

Knowledge of the visual pathway enables you to predict the deficits resulting from damage anyplace in the pathway; knowledge of a little terminology allows you to name them (Fig. 17-5) and bewilder the uninitiated. Deficits are generally named for the visual field affected. Heteronymous means the affected fields of the two eyes do not overlap and homonymous means the affected fields overlap to a greater or lesser degree. Therefore, damage in front of the optic chiasm affects only the eye ipsilateral to the damage, damage to the optic chiasm typically causes heteronymous deficits, and damage behind the chiasm causes homonymous deficits. Terms like hemianopia and quadrantanopia mean half or a quarter of a visual field is nonfunctional.

Primary Visual Cortex Sorts Visual Information and Distributes It to Other Cortical Areas

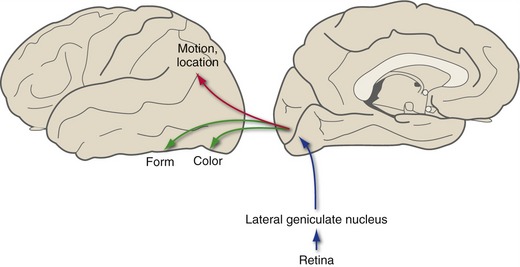

Visual Information Is Distributed in Dorsal and Ventral Streams

A second major function of visual cortex, once the various elements of visual stimuli have been sorted out, is to export information about these elements to specific areas of visual association cortex that are specialized to deal with them. Thus, there are visual association areas particularly interested in the color of an object, its distance from the eyes, details of its shape, the direction and velocity of movement, and other properties. Although the segregation of functions is far from complete, in general more dorsal areas process information about location and movement and more ventral areas process information about color and form (Fig. 17-6). As a result, rare, selective lesions in visual association areas can cause a selective loss of only some visual capabilities—even something as specific as the ability to recognize faces (THB6 Box 17-2, p. 451).

Early Experience Has Permanent Effects on the Visual System

The basic wiring pattern of the visual system is genetically determined and present at birth. However, there is a period of plasticity early in life during which visual experience is critical for refining and even maintaining these connections (see Chapter 24). Anything that interferes with normal binocular vision during this period (e.g., cataracts, misalignment of the eyes) can cause permanent changes in connections and permanent visual deficits. The duration of the critical period of plasticity varies from cortical area to area and from species to species, but may be as long as several years in humans.

Reflex Circuits Adjust the Size of the Pupil and the Focal Length of the Lens

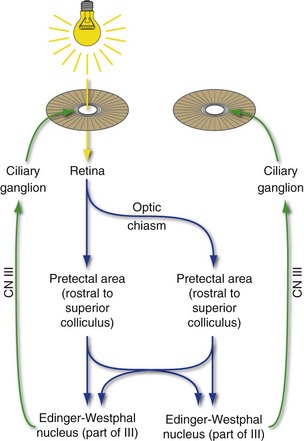

Illumination of Either Retina Causes Both Pupils to Constrict

The size of the pupil is determined by the balance between a relatively strong sphincter and a relatively weak dilator (Fig. 17-7). The sphincter receives parasympathetic innervation via the oculomotor nerve and the ciliary ganglion and is normally activated during the pupillary light reflex and the near reflex (next section). The dilator receives sympathetic innervation via the intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord and the superior cervical ganglion. The preganglionic sympathetic neurons for the dilator can be activated by long descending pathways from the ipsilateral half of the hypothalamus, as well as by other routes.

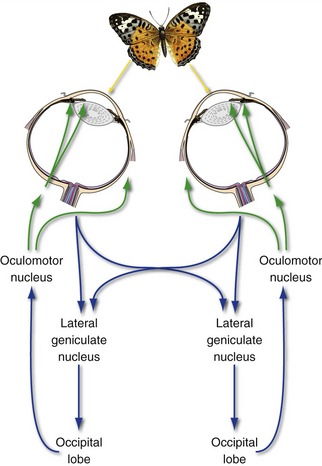

A commonly tested cranial nerve reflex is the pupillary light reflex (Fig. 17-8). Light shone through one pupil causes both sphincters to contract equally. The response of the illuminated eye is the direct reflex, and the equal response of the unilluminated eye is the consensual reflex. Afferent impulses for this reflex arc travel along ganglion cell axons in the optic nerve; half of these cross in the optic chiasm. However, they bypass the lateral geniculate nucleus and travel instead through the brachium of the superior colliculus to the pretectal area, just rostral to the superior colliculus at the midbrain-diencephalon junction. Fibers from the pretectal area then distribute bilaterally to the Edinger-Westphal subnucleus of the oculomotor nucleus, where the preganglionic parasympathetic neurons live. Because of the bilateral distribution of fibers both in the optic chiasm and in going from each pretectal area to the oculomotor nuclei, light in one eye causes equal constriction of both pupils. Optic nerve damage produces equal pupils, neither one of which responds to light shone into the eye ipsilateral to the damage, but both of which respond normally to light shone into the contralateral eye. Oculomotor nerve damage, in contrast, causes a dilated ipsilateral pupil that does not respond to light shone into either eye.

Both Eyes Accommodate for Near Vision

Looking at something nearby causes three things to happen in reflex fashion: (1) Both medial recti contract, converging the eyes; (2) both ciliary muscles contract, allowing the lens to fatten (accommodation) and thus focus the image of the nearby object on the two retinas; and (3) both pupillary sphincters contract, improving the optical performance of the eye. Because this near reflex or accommodation reflex typically involves consciously looking at something, it is not surprising that its pathway involves a loop through visual cortex (Fig. 17-9). The afferent limb is the standard visual pathway through the lateral geniculate nucleus and visual cortex. After one or more synapses in the occipital lobe, the efferent limb involves a projection back through the brachium of the superior colliculus to the pretectal area and/or the superior colliculus and from there to the oculomotor nucleus. (The stop in the superior colliculus is omitted from Fig. 17-9 for simplicity.)